Elias Hill

Elias Hill | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1819 |

| Died | March 28, 1872 (aged 52–53) |

| Occupation(s) | Preacher, civil rights activist |

| Political party | Republican |

Elias Hill (c. 1819 - March 28, 1872) was a Baptist minister and leader of a York County, South Carolina congregation that emigrated to Arthington, Liberia. In May 1871, during the Reconstruction era, he was among the victims in a series of attacks in York County against local blacks by members of the Ku Klux Klan. His situation received wide attention on account of his condition, as Hill had been stricken by an illness while a child which had left him crippled with his arms and legs in a withered state. He was known for preaching about rights and equality, and taught local children how to read and write.

Early life

[edit]

Elias Hill was born in 1819 to Dorcas and Elias in York County, South Carolina. The elder Elias was possibly born in Africa.[1] He was stricken with a disease at age seven in 1826 which left him crippled. Some observers described him as a dwarf, and he described the disease as rheumatism, but it was probably polio.[2] It may also have been muscular dystrophy; in any case, he was crippled in one arm and leg. As an adult, his legs remained extremely skinny, his arms were withered, and his jaw was deformed. While still young, Hill's father purchased the freedom of his wife, Hill's mother, for $150. Hill's master included the crippled boy in the transaction.[3]

The Hills were owned by a famous Hill family, which included future Confederate general Daniel Harvey Hill. As a boy, Elias learned to read and write from white school children in York County. No one objected to having such a compromised child hanging around the school. Thus Hill gained certain privileges, but he was also ridiculed for his condition by other children.[3] Daniel Harvey Hill was among those who taught Elias to read.[2] Elias was very intelligent and driven, and his intellectual possibilities were not noticed by the white community around him due to his condition.[3]

After the Civil War ended in 1865, Hill worked as an ordained Baptist preacher moving from congregation to congregation in the South Carolina Piedmont. He also taught reading and writing.[2] By 1871 at the age of 50 he was president of the local Union League. He regularly held political meetings at his cabin and was a popular and powerful preacher,[3] serving a congregation in Clay Hill, near Rock Hill, South Carolina.[2]

Lynchings of Jim Williams, Solomon Hill, and June Moore

[edit]

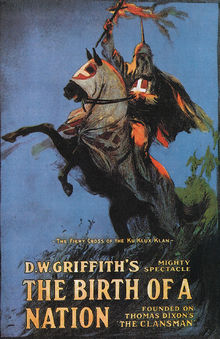

In February 1871, Hill met with local Ku Klux Klan (KKK) leaders to negotiate the safety of blacks in the community. The KKK worked to impose white supremacy in the postwar South. Around February 12, eight black men were killed by 500 to 700 whites in black gowns with masks; these murders were followed by nightly Klan raids for months.[2]

After the Civil War, ex-slave and Union veteran Jim Williams returned to York County and began work with Hill for the civil rights of blacks. Williams led a black militia group, one of what were known as Union Leagues. Some whites claimed Williams had threatened to kill local whites and that Williams's militia was stockpiling weapons. They also repeated a rumor that Williams claimed to desire to rape white women if he could. On March 6, 1871, about forty men seized Williams from his home and hanged him from a tree, also shooting him with many bullets. Local KKK leader J. Rufus Bratton, brother of Williams's former owner John S. Bratton, was said to have placed the noose around Williams' neck. Williams was subsequently brought to Bratton's office where Bratton, in his medical capacity, served the inquest.[5]

The mob visited several other homes of men involved in the Union League militia, succeeding in gathering 23 guns but no other members. Members of the league swore vengeance, but did not act. Companies B, E, and K of George Armstrong Custer's Seventh U.S. Cavalry led by Major Lewis Merrill arrived in the area to try to quell the violence,[6] Hill stepped in to lead the League, now in disarray. In another raid, Hill's nephews, Solomon Hill and June Moore, were attacked and forced to renounce their Republican Party affiliation in the local paper, the Yorkville Enquirer.[2]

Assault on Elias Hill

[edit]On May 5, 1871, a masked neighbor came to Hill's brother's cabin, which was next door to Hill's own. The neighbor slapped Hill's sister-in-law, demanding to know where the "uppity" Hill resided. Next, Hill was dragged by his arms and legs into the yard and beaten with a horsewhip. He was charged with denouncing the KKK, inciting a riot, and ravishing white women. They threatened to throw him in the river and told him to desist preaching against the KKK.[3] The Klan also demanded Hill denounce the Republican Party, as had his nephews, and cancel his subscription to the Republican paper.[7]

This was the first episode of Ku Klux Klan violence which Merrill witnessed in York County, and he was unable to step in to protect the black citizens. Eight days after the attack, Merrill met with community leaders demanding change, although violence continued over the summer.[3] Merrill's efforts eventually led to the dismantling of much of the Klan in the county. But Bratton, who ran away to Canada for a number of years to escape prosecution, was never successfully prosecuted.[8]

Emigration to Liberia

[edit]Hill was afraid for his life and contacted Congressman Alexander S. Wallace and the American Colonization Society, seeking to escape the United States. Along with 135 other blacks, he sailed across the Atlantic to settle in Liberia in October 1871. Before leaving, he testified before a congressional committee that emigration was the best solution: "We do not believe it is possible from the past history and present aspect of affairs, for our people to live in this country peaceably and educate and elevate their children to any degree which they desire."[3] At least 21 of the 31 households that were part of the Clay Hill emigrant group either had suffered Klan attacks or had near relatives in York County who had been victims. "That is the reason we have arranged to go away," Hill said.[2]

The congregation boarded the Charlotte, Columbia and Augusta Railroad and traveled to Charlotte, North Carolina, and then to Portsmouth, Virginia. They sailed to Liberia on the Edith Rose, a trip that included 243 regular passengers and two stowaways, all former slaves like Hill, except for the youngest and a few freedmen. The group settled in Arthington, Liberia.[2]

Life in Liberia and death

[edit]Arthington had been founded in 1869 by Alonzo Hoggard and his congregation from Bertie County, North Carolina. In 1870, John Roulhac and his party arrived. In 1871, parties led by Jefferson Bracewell and Elias Hill arrived, and in 1872 another group led by Aaron Miller came.[9]

Conditions in Liberia were much worse than colonists had been told. Colonists believed that mortality and illness were low. However, as many as 20% of immigrants would die of malaria. And Hill discovered when he arrived that the government was in "great disorder". Liberia's president, Edward James Roye, was overthrown in late 1871 in the wake of a financial scandal and was assassinated in early 1872. Hill died of malaria on March 28, 1872, after only six months in Liberia.[10]

Legacy

[edit]The Clay Hill congregation remained in Arthington. Hill and Moore, run by Hill's nephews, became a major firm in Liberia and its success enabled the pair to endow a nearby Baptist institute.[2]

In Albion W. Tourgée's book, Bricks Without Straw (1880), the character of Eliab Hill was based in part on Elias Hill.[11]

The story of Elias Hill also inspired Katharine DuPre Lumpkin's novel Eli Hill, which was written in the 1950s and published in 2020 by University of Georgia Press.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ Representatives, USA House of (1872). House Documents. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Witt, John Fabian. Patriots and Cosmopolitans: Hidden Histories of American Law. Harvard University Press (2009), p.85-86, 128-149

- ^ a b c d e f g Martinez, James Michael. Carpetbaggers, Cavalry, and the Ku Klux Klan: Exposing the Invisible Empire During Reconstruction. Rowman & Littlefield (2007), p.76-78

- ^ West, Jerry Lee. The Reconstruction Ku Klux Klan in York County, South Carolina, 1865-1877. McFarland (2002), p. 126-130

- ^ Gillin, Kate Côté. Shrill Hurrahs: Women, Gender, and Racial Violence in South Carolina, 1865-1900. Univ of South Carolina Press (2013)

- ^ Martinez, James Michael. Carpetbaggers, Cavalry, and the Ku Klux Klan: Exposing the Invisible Empire During Reconstruction. Rowman & Littlefield (2007), p.1-5

- ^ Wade, Wyn Craig. The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America. Oxford University Press (1998)

- ^ Pearl, Matthew (March 4, 2016). "K Troop". Slate.com.

- ^ Tayloe, Henry. "Letter from Mr. Henry Tayloe, New York, August 1884," in The African Repository, Volumes 60-62, American Colonization Society (1886), p. 125-126

- ^ Witt, John Fabian. Patriots and Cosmopolitans: Hidden Histories of American Law. Harvard University Press (2009), p.146-148

- ^ Schmidt, Peter. Sitting in Darkness: New South Fiction, Education, and the Rise of Jim Crow Colonialism, 1865-1920. Univ. Press of Mississippi (2010), p.222

- ^ Lumpkin, Katharine Du Pre (2020-04-22). Eli Hill: A Novel of Reconstruction. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-5719-5.