Edward Wilkinson (bishop)

Edward Wilkinson | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Zululand Coadjutor Bishop of London for north and central Europe | |

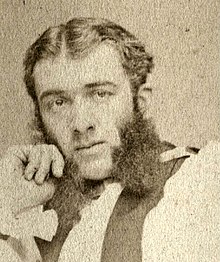

T.E. Wilkinson, 1870 | |

| Church | Anglican |

| Province | Southern Africa |

| Diocese | Zululand |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 26 December 1837 Walsham-le-Willows, Suffolk, United Kingdom |

| Died | 23 October 1914 (aged 76) Khartoum, Sudan |

| Signature |  |

Thomas Edward Wilkinson (1837−1914), known as Edward Wilkinson, was an Anglican bishop, legionnaire and travel writer in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The sixth child of a gentleman farmer, he was born at Walsham Hall, Walsham le Willows, Suffolk. Before he was ordained, he joined the French Foreign Legion and travelled around Europe.

As a priest he had the curacies of two consecutive parishes, then spent six years with his wife and children in South Africa as the inaugural Bishop of Zululand. Following a Cornwall incumbency, he was concurrently the rector of St Katherine Coleman, London, and coadjutor bishop of London for north and central Europe. Within this diocese he had the oversight of missions across ten nations. To reach all of his European chaplaincies meant a journey of over 14,000 miles; he made 82 of these episcopal tours.

He published several books, including a Zulu hymn book, an edition of his wife's Zululand journals, and his own travel book relating to his years in Europe. In his Who's Who entry, Wilkinson listed his recreation as "work".

Background

[edit]Parentage

[edit]Wilkinson's father was Hooper John Wilkinson, (1800–1883),[1] a magistrate and proprietor of a 240-acre (97 ha) farm employing eight labourers and four boys in 1851.[2] His mother was Anne née Howlett (c. 1805–1884).[3][4][5][6] Hooper John, Anne and their son Octavius are buried in the churchyard of St Mary's Church, Walsham le Willows.[7]

Thomas Edward Wilkinson was the sixth son, having at least ten siblings. He was born at Walsham Hall, Walsham le Willows, Suffolk on 26 December 1837.[8][9] His eldest brother was barrister Hooper John Wilkinson (1822–1904).[10][11] His other elder brothers were George Howlett (1828–1879),[12] Charles Ellis (born 1829), Harry Evan "Henry" Wilkinson (born 1834) and Rev. Octavius (1836–1870).[13] Octavius attended Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and was made priest alongside his brother Thomas Edward.[5][14] The youngest brother was Joseph Henry Newman (born 1850).[15] His sisters were Anne (born 1824), Mary Ann (born 1826), Elizabeth Frances (born 1833) and Edith Margaret (born 1847).[2][16][17][18]

Family home

[edit]The 17th-century red-brick Walsham Hall was built on the site of an ancient manor house.[19] H. J. Wilkinson purchased the property in 1828, rebuilt the hall, and was living in it by 1841. T. E. Wilkinson inherited the house and sold it to the Church of England, later adding some land to the gift. The house was renamed as Walsham Farm Home and opened as a Church of England children's home in 1896. The home closed in 1921, was sold, and became a school. After serving as various private residences, the building was demolished in 1968. The classical-styled Willow Court and Willows House now stand on the site.[4]

-

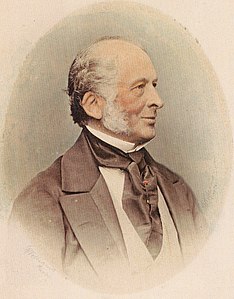

Hooper John Wilkinson, Wilkinson's father

-

Ann Howlett, Wilkinson's mother

-

Walsham Hall, Wilkinson's birthplace

Education

[edit]Wilkinson was educated at Bury St Edmunds grammar school and King's College London. He was admitted on 10 May 1856 at age 18 to Jesus College, Cambridge, where his 1902 portrait hangs.[20] He received his BA on 8 December 1859,[21][5] his MA on 16 April 1863,[22] and his DD on 19 May 1870.[5][23]

Marriage

[edit]

At St Peter and St Paul Church, Foxearth, Essex, on 18 August 1864,[24] Wilkinson married Annie Margaret Green (Bedford 1844 – St Austell 1878).[25][26][27][28] She was the daughter of coal and timber merchant Thomas Abbot Green JP (b. Great Gaddesden 13 April 1806) of Felmersham in Bedfordshire.[29] Green spent "several thousand pounds" in 1842 in transforming his house Felmersham Grange into "an Elizabethan-style mansion", and he was a benefactor to the Church of St Peter, Pavenham.[30] After Annie died, Wilkinson had steps and gates installed at the west side of the Church of St Mary, Felmersham, in her memory.[31] In her published compilation of letters to friends and relatives, and journals relating to Zululand, Annie refers to her husband as "E." This is because Wilkinson used the forename Edward, rather than Thomas.[32][33]

The couple had three sons and four daughters:[34] The eldest son was Edward H. (b. Ricklinghall 1866).[32][35] Two of the daughters were Ethel Mary (Ricklinghall 1869 – Exmoor 1941)[36][37][38] and Edith Howlett (Natal 1870 – Taunton 1960).[39][40] Edith's son was Edward John Nelson Wallis C.B.E., governor of Khartoum.[41] Then came Annie Howlett (Zululand ca.1872 – Oxford 1897),[42] Fitzgerald Hooper (Transvaal ca.1875 – Ealing 19 September 1933),[43] Irene Douglas (Newton Abbot 1876 – Sturminster Newton 1970),[44][45][46] and World War I soldier Kenneth James Hooper (Newton Abbot 1878 – Taunton 1948).[47][48][49] On 11 June 1890, Wilkinson's eldest daughter Ethel Mary Wilkinson married Rev. George Richard Mullens M.A. of East Woodhay.[36][50] On 23 October 1907 Wilkinson conducted the marriage of his youngest daughter Irene Douglas Wilkinson and Arthur Frederick Wallis at St Giles Church, Taunton, where Irene was a Sunday school teacher. On the day of the marriage, the church and churchyard were decorated with flowers, the villagers attended, and the local children presented gifts to the couple.[44]

By 1895 Wilkinson was living at 42 Norfolk Square, Paddington, and asked for his name to be added to the electoral roll. In spite of his bishopric and the Reform Act 1867 his request was refused on the grounds that the house belonged to his sister Miss Wilkinson, so as her tenant he had no right to vote.[51] His last home address was Bradford Court, Taunton.[34]

Death

[edit]Wilkinson's last home was Bradford Court, Taunton,[52] but he died of dysentery at 3:45 am on 23 October 1914 at Khartoum, while travelling in a non-clerical capacity between Cape Town and Cairo.[53][9] Wilkinson's funeral took place on the day of his death,[54] and he is buried at Khartoum. Since he had previously requested it, a stone Celtic cross was erected in the churchyard of St Mary's, Felmersham. The memorial's inscription says that it is also in memory of "the dear ones lying around this churchyard".[31] He left £50,786, net £46,536.[52] To his daughter Edith Howlett Wallis he left "the ikon presented to him by the Metropolitan of Petrograd,[nb 1] and his episcopal pastoral staff, mitre and pectoral cross".[55]

Career

[edit]In his Who's Who entry, Wilkinson listed his recreation as "work".[34] However, before he was ordained "he went to Italy with the intention of joining Garibaldi's English contingent and travelled over most of Europe."[54] Wilkinson was ordained deacon by Thomas Turton at Ely Cathedral in 1861, and priest on 16 March 1862.[54][5][56] After a curacy at St Mary the Virgin's Church, Cavendish between March 1861 and 1864,[57][58] Wilkinson had the curacy of St Mary's Church, Rickinghall Superior between 1864 and 1870.[5][59] In 1870, after Bishop John Colenso "was removed by Archbishop Gray of Capetown for preaching a liberal interpretation of the Bible to his Zulu converts",[60] he became the inaugural Bishop of Zululand.[5][61][62] He held the post until 1876. On his return to England he was rector of St Michael Caerhays between 1878 and 1882,[5][63][64] and then rector of St Katherine Coleman, London, between 1886 and 1911.[65] For twenty-five years between 14 August 1886 and 1911 he was coadjutor bishop of London for north and central Europe,[5][9][66] having been nominated by Frederick Temple.[54][67]

On 30 December 1865, Wilkinson wrote a long letter to the Evening Mail about the need to establish local hospitals for infectious diseases, and the need to train nurses throughout the country. He described the previous year's epidemic of fevers in the parishes of Ricklinghall Superior and Inferior, and the despair of local families regarding how to assist a patient. He said,[68]

"I have myself stepped in upon one occasion and found a mother of a large, grown-up family, and who, therefore, ought not to have been so entirely destitute of common sense, actually bending over her son, a lad of 16, who lay prostrate from a terrible attack of scarlet fever, and was begging him, in his insensible state, to open his clinched teeth to admit what the doctor had ordered her to give him; and there he would have laid, and died too, had I not most providentially called in the midst of the scene and let the liquid percolate from time to time between his teeth, from which time he happily slowly began to recover."[68]

On 13 March 1884, Wilkinson confirmed 111 children at All Saints Church in Faringdon. He read them a very long sermon on how to be good. Then the children were given another service and sermon by the vicar of Faringdon in the evening.[69]

Zululand bishopric, 1870–1876

[edit]In 1870, Wilkinson established himself at the mission station which had been built at KwaMagwaza, South Africa in 1859, when the Anglican Diocese of Zululand was created, following an agreement between Bishop John Colenso and King Mpande. By 1870, KwaMagwaza's chief missionary Archdeacon Robert Robertson was no longer cooperating with Colenso, who had been excommunicated, so on 8 May at the Whitehall Chapel Wilkinson had been inducted the inaugural Bishop of Zululand, "a bishop for the Zulus and the tribes towards the Zambezi".[62] On his arrival in South Africa, Wilkinson was challenged by Colenso who did not want to leave. However he "did good work in a difficult sphere",[54] and began his bishopric by establishing missions at Mpumalanga and Swaziland. Wilkinson resigned the post in 1876. In 1879 the Anglo-Zulu War broke out, the missions set up by Wilkinson were destroyed, and the British Army was defeated at Isandlwana. Due to the unrest, it was not until 1880 that Zululand had a second bishop, in the person of Douglas MacKenzie.[62]

North and Central Europe bishopric, 1886–1911

[edit]His next appointment was as coadjutor bishop of London, starting in March 1886.[70] (He held this with the living of St Katherine Coleman.)[71] During Wilkinson's era, the area encompassed by this diocese comprised ten nations: Russia, Austria, Germany, Switzerland, France, Belgium, Holland, Denmark, Sweden and Norway, where at that period ruled three emperors and five kings, some of whom were Anglicans. These countries between them hosted two million annual tourists and seventy thousand expatriate British subjects. International trade annually brought two hundred and thirteen thousand British sailors to the ports.[72] This position gave Wilkinson "the oversight of 90 permanent chaplaincies in [the north and central European] region",[73] plus 200 seasonal chaplaincies. To visit them all meant travelling over fourteen thousand miles.[72] He made 82 episcopal tours during this bishopric which was "lying over an area eight times the size of Great Britain, and entailing very broken and trying travel by land and sea". He oversaw the construction of twenty-one churches;[73] for example on 22 April 1910, Wilkinson consecrated St. Boniface Church, Antwerp,[31] and St Ursula's Church, Bern, on 20 September 1906.[67] So after 25 years of this, in January 1911 he saw fit to retire at the age of 64 years.[73][74] The following extract from his 1906 memoirs gives a partial insight into his concept of baptism and naming:[75]

From Freiburg I went to Berne, staying with Mr. Leveson-Gower, attached to the Legation.[nb 2] I received his little son into the Church in the cathedral of Berne, the old dean being present. Mr. Leveson-Gower wished the additional name of Clarence to be given him, being descended from the Duke of that name, - said to have met his end in a butt of malmsey wine - but as the names of Osbert Charles Gresham had been already given him at his baptism, he had to be content with them![75]

In 1906, Wilkinson wrote to the Central Somerset Gazette to advocate the rebuilding of the Glastonbury Abbey ruins as a training college for missionaries.[76] Nothing came of it, and in the event the Bath and Wells Diocesan Trust bought it in 1908; since then it has been protected as an archaeological site.[77]

On the second day of the 1907 Church Congress at Great Yarmouth Royal Aquarium,[nb 3] Wilkinson as Bishop of Northern and Central Europe read a long paper on the subject of The present condition of religious life on the continent of Europe and their lessons for the Church of England today. He declared that Germany was a religious nation, and that France was certainly not. He criticised the "uncatholic claims of Rome to universal authority". He said that Russia was a "great Christianising power" (he did not live to see the Russian Revolution). Those statements may appear judgmental, however he also made one comment which may possibly define the middle road that he had to take in Africa, when the previous bishop, Colenso, had been excommunicated for questioning the literal truth of the Bible and for saying as Bishop of Natal, "that his aim was to defeat sin rather than to punish those who sinned",[78][79] and when Wilkinson himself had to continue the mission while respecting the same African cultures. Wilkinson said, "In ministering to our own countrymen we should take heed of the lessons of the Eastern Church: never to interfere; to exercise the utmost care in no way to do what Rome is ever doing, i.e. to proselytise."[79]

Burgess Hill connection

[edit]

Wilkinson was a close friend of Rev. W.R. Tindal-Atkinson of St Andrews Church, Burgess Hill. He used to visit periodically, and "had taken a keen interest in the development of St. Andrew's parish and the building of St. Andrew's Church, the pulpit of which he occupied on several occasions. His visits were always associated with special and successful financial efforts on the part of the parishioners."[54] In the event, there were two new churches. The first, known as the tin oven due to its lack of summer insulation, was the 1899 corrugated iron church, bought second hand from East London, under the new curacy of Tindal-Atkinson. In 1900 the tin oven gained a sanctuary and basement. It continued as a church until 1908, after which it became the church hall. It burned down in 1959. The second, more substantial one, designed by Norman & Burt of Burgess Hill, had only a nave during Wilkinson's lifetime. The building was completed with the addition of a sanctuary in 1924, and as of 2020 was still in use as a church.[80]

Travel writing

[edit]

A stuffy, desk-bound bishop, Wilkinson was not. The following extracts show something of the personality of the man. Here he recounts part of a journey between Bern and Lausanne in 1886:[75]

From Geneva I went to Thun, Interlaken, and Grindelwald, at each of which places we have season chaplaincies ; in fact, all Switzerland is studded – mountains, lake-sides, and valleys – with what I call my button mushroom churches, for they spring up all over that country, and sometimes almost in a night! On my way I ascended the Schynige Platte,[nb 4] from which a fine view of the Oberland is obtained. A farmer's son at Grindelwald told me that corn and apple trees will grow now in that district, whereas in his father's day, when the glaciers came much further down into the valley, neither could be cultivated. His father, who died this spring at the age of seventy-six, told him that this would take place again when the glaciers come down, as they are sure to do, in course of time. Sleeping at the Männlichen, then a rough hut far above the Wengen Alp Hotel,[nb 5] a grand panorama of the Jungfrau and the Oberland giants was obtained. The whole range, from the Titlis to Diablerets, lay in view. When in that neighbourhood I saw several rare birds, ring ousels, snow buntings, and, much to my delight, several Cornish choughs.[nb 6][75]

Wilkinson may have spent years in Africa, but he apparently liked snow sports. Here he is in 1895:[75]

I ran down to Thun one day from Berne and found it completely snowed up. Judging from appearances, all the inhabitants, save a few enterprising boys who were tobogganing down the deserted streets, in bed and asleep. As the boys did not invite me to join their sport, I returned to Berne by the next train.[75]

This first bishop of Zululand was a sharer of stories. Here is one story that he heard from Frederick Robert St John, the chargé d'affaires at Berne, in 1895. It is not known whether either man embellished it:[75]

His most remarkable journey was from Pekin to England by land, long before the Trans–Siberian Railway was dreamed of – a wonderful feat for that day. It took him six weeks to reach the Siberian frontier, thence by sledge, with a young Russian officer carrying dispatches through Siberia to Nizhny Novgorod. They were eighteen days and nights in a sledge, travelling as hard as relays of three horses could lay their legs to the ground – and Russian horses can lay them to the ground. I remember Mr. J. Hubbard, of Petersburg, accustomed to Russian sledge travelling, telling me that upon a journey of only three or four days over the Ural Mountains he had to tie up his jaw tight to prevent his teeth being broken by the shocks over what are called roads! I was not surprised when Mr. St. John told me that he did not sleep for six months afterwards, and had never been altogether the same man since. The young Russian officer became delirious at the end of the first week, which terribly aggravated the difficulties and hardships of the journey.[75]

Here is Wilkinson in the same winter of 1895.[75]

After a reception I endeavoured to walk out upon the Thun Road, where I found Mr.St John in almost as great a plight as in his journey from Pekin to London. He had got into a deep snowdrift returning from the reception to his house, and would have probably remained there till a thaw set in had I not come along and delivered him out of his distress ... An hotel somewhere up in the Jura was reported as buried fifteen feet deep. From many farm-houses tunnels had to be made to cow-houses, stables, and outbuildings to feed the cattle. Whole chalets were completely buried. In one, a man and his wife were found dead; their little child was alive under a table, warmed by a big dog which had curled itself round its young friend.[75]

Published works

[edit]- Wilkinson, Thomas Edward, (1874) Hymns Ancient and Modern, translated into the Zulu language.[5][34]

- Wilkinson, Thomas Edward (1875). A Suffolk Boy in East Africa. London: Christian Knowledge Society. ISBN 978-1-7186-4668-1. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Wilkinson, Annie Margaret Green (1876). Wilkinson, Thomas Edward (ed.). A Lady's Life in Zululand and the Transvaal during Cetewayo's Reign; the late Mrs Wilkinson's journals. London: Christian Knowledge Society or J.T. Hayes Covent Garden. Retrieved 31 August 2020 – via Internet Archive.[nb 7][5][34]

- Wilkinson, Thomas Edward, (1894) Emigration, the True Solution of the Social Question.[5][34]

- Wilkinson, Thomas Edward, (1894) Does England Wish her Boys and Girls to Grow Up Atheists and Anarchists?.[34]

- Wilkinson, Thomas Edward, (1898) Saat, the Slave Boy of Khartoum.[5][34]

- Wilkinson, Thomas Edward (1906). Twenty Years of Continental Work and Travel. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. ISBN 978-1-376-67037-0. Retrieved 16 August 2020. (There is also an Internet Archive online version)

Notes

[edit]- ^ During Wilkinson's bishopric, the Metropolitan of Petrograd was probably Oknov Pitirim

- ^ Mr Leveson-Gower was probably Granville Leveson-Gower, 3rd Earl Granville, who was then serving in Europe in Her Majesty's Diplomatic Service.

- ^ The Great Yarmouth Royal Aquarium was built in 1883 as an aquarium, and by 1896 it was a theatre. In 1992 it became the Hollywood cinema, and as of 2020 it still stands.

- ^ He ascended on foot; the Schynige Platte Railway was not built until 1893.

- ^ The Wengernalp Railway was not opened until June 1893, so much of Wilkinson's Alpine travel in 1886 was on horseback or on foot.

- ^ The Cornish chough is red-billed, and breeds at a lower elevation than the Alpine chough which is yellow-billed. It is not impossible that he saw the red-billed chough, and its rarity at that height may explain his surprise. It is not known which one he saw.

- ^ Cetewayo was Cetshwayo kaMpande.

References

[edit]- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020. Deaths Jun 1883 Wilkinson Hooper John 83 Stow Suffolk 4a 392

- ^ a b "1851 England Census HO107/1794 p.6 schedule 57". Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ "1841 England Census HO107/1014/13 p.18 schedule 35". Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ a b Champion, John (January 2009). "Review number 48, January 2009, Walsham Hall". walsham-le-willows.org. Walsham le Willows. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Wilkinson, Thomas Edward (WLKN856TE)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.Deaths Jun 1884 Wilkinson Anne 79 Thingoe 4a 343

- ^ "Walsham le Willows". Bury Free Press. British Newspaper Archive. 28 June 1884. p. 12 col.6. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020. Births Mar 1838 Wilkinson Thomas Edward Stow Suffolk 12 407

- ^ a b c "Death of Bishop of Zululand on journey from Cape to Cairo". Edinburgh Evening News. No. 12,963. 22 October 1914. p. 9 col F. Retrieved 2 September 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Wilkinson. Foster's hand list of men at the bar. 1800s. p. 506. ISBN 978-1-295-72919-7. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020. Deaths Sep 1904 Wilkinson Hooper John 81 Brighton 2b 135

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020. Deaths Mar 1879 Wilkinson George Howlett 51 Ipswich 4a 496

- ^ "Deaths". Diss Express. British Newspaper Archive. 6 May 1870. p. 4 col.5. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "Bishop of Ely". Cambridge Chronicle and Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 22 March 1862. p. 6 col.1. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020. Births Sep 1850 Wilkinson Joseph William Newman Stow XII 459

- ^ "1861 England Census RG9/71 p.15 schedule 15". Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ "1871 England Census RG10/1791 p.37 schdule 138". Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 25 August 2020. Births Dec 1847 Wilkinson Edith Margaret Stow XII 403

- ^ "Hall House". walsham-le-willows.org. Walsham le Willows Parish Council. 2020. Archived from the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Portrait of T.E. Wilkinson". janus.lib.cam.ac.uk/. Cambridge Antiquarian Society portrait collection. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2020. The portrait is an autotype from a drawing, ref. CAS E84, made c. 1902

- ^ "University graces". Cambridge Independent Press. British Newspaper Archive. 10 December 1859. p. 5 col.4. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "University intelligence, Cambridge April 16". Morning Post. British Newspaper Archive. 17 April 1853. p. 6 col.3. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Degrees conferred". Cambridge Chronicle and Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 21 May 1870. p. 4 col.4. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ "Marriages". Hertfordshire Express and General Advertiser. British Newspaper Archive. 27 August 1864. p. 2 col.5. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020. Births Dec 1844 Green Annie Margaret Bedford VI 36

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020. Deaths Sep 1878 Wilkinson Annie Margaret 33 St Austell 5c 80

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020. Marriages Sep 1864 Wilkinson Thomas Edward, and Green Annie Margaret, Sudbury 4a 593

- ^ "Married". Norfolk Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 27 August 1864. p. 5 col.7. Retrieved 17 August 2020. Marriage - at end of list

- ^ 1851 England Census HO107/1872 p.24 schedule 268

- ^ "Joseph Tucker Burton Alexander estate deeds (Pavenham Bury)". bedsarchivescat.bedford.gov.uk. Bedfordshire Archives Service Catalogue. 1882. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Shrimpton, Kenneth. "Some thoughts on inscriptions in St Mary's Church Felmersham: Bishop Wilkinson died 1914". felmersham.net. Felmersham.net Journal. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Annie Margaret (1876). Wilkinson, Thomas Edward (ed.). A Lady's Life in Zululand and the Transvaal during Cetewayo's Reign; the late Mrs Wilkinson's journals. London: Christian Knowledge Society.

- ^ "Historical papers research archive: AB2925.D3.1". historicalpapers.wits.ac.za. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Who Was Who 1897-1916 (PDF). Bloomsbury, London: A & C Black. 1916. p. 763. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 31 August 2020. Births Jun 1866 Wilkinson Edward H. Hartismere 4a 547

- ^ a b "Borough notes". Marylebone Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 31 May 1890. p. 3 col.1. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020. Births Jun 1869 Wilkinson Ethel Mary Hartismere 4a 520

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 25 August 2020. Deaths Sep 1941 Mullens Ethel M. 72 Exmoor 5c 547

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 25 August 2020. Marriages Mar 1900 Wilkinson Edith Howlett and Wallis John Nelson, Marylebone 1a 837

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020. Deaths Dec 1960 Wallis Edith H. 89 Taunton 7c 260

- ^ "Notice". Morning Post. British Newspaper Archive. 17 November 1899. p. 5 col.7. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020. Deaths Dec 1897 Wilkinson Annie Howlett 25 Oxford 3a 498

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020. Deaths Sep 1933 Wilkinson Fitzgerald H. 59 Brentford 3a 194

- ^ a b "Fashionable marriage: Mr A.F. Wallis and Miss Irene D. Wilkinson". Taunton Courier, and Western Advertiser. British Newspaper Archive. 30 October 1907. p. 3 col.3. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 25 August 2020. Births Dec 1876 Wilkinson Irene Douglas Newton Abbot 5b 126

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020. Deaths Dec 1970 Wallis Irene Douglas 14 Au 1876 Sturminster 7c 368

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020. Births Mar 1878 Wilkinson Kenneth James H. Newton A. 5b 141

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 25 August 2020. Deaths Dec 1948 Wilkinson Kenneth J.H. 71 Taunton 7c 189

- ^ "The late Mr K.J.H. Wilkinson Bradford on Tone". Taunton Courier, and Western Advertiser. British Newspaper Archive. 18 December 1948. p. 2 col.7. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020. Marriages Jun 1890 Wilkinson Ethel Mary Marylebone 1a 1122

- ^ "The registration courts". London Evening Standard. British Newspaper Archive. 1 October 1895. p. 3 col.5. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Bishop Wilkinson's estate, owner of Bradford Court". Central Somerset Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 8 January 1915. p. 5 col.6. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ The Times, Saturday, 24 October 1914; pg. 8; Issue 40675; col A Death Of Bishop Wilkinson. Work On The Continent And In South Africa

- ^ a b c d e f "Death of Bishop Wilkinson, a periodic visitor to Burgess Hill". Mid Sussex Times. British Newspaper Archive. 3 November 1914. p. 3 col.5. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ "Local wills". Taunton Courier, and Western Advertiser. British Newspaper Archive. 6 January 1915. p. 6 col.7. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "University intelligence". Norfolk Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 22 March 1862. p. 3 col.2. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Licensed to curacies". Bucks Herald. British Newspaper Archive. 9 March 1861. p. 3 col.2. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "1861 England Census RG9/1132 p.1 schedule 15". Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ "Thomas Edward Wilkinson (letter to Nightingale Fund Company)". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. The National Archives. May 1867. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ Wilkinson, Richard William (March 1985). A History of Hymns Ancient and Modern (Doctoral thesis). University of Hull. p. 5. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Archibald, Carol (1998). "Historical papers research archive: AB2546 ARCHBISHOPS OF CAPE TOWN PART III". historicalpapers.wits.ac.za/. University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ a b c "Our history". zululanddiocese.co.za. Anglican Diocese of Zululand. 2020. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "The Clergy List, Clerical Guide and Ecclesiastical Directory" London, Hamilton & Co 1889

- ^ "Ecclesiastical appointments in the diocese of Truro". Royal Cornwall Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 19 July 1878. p. 4 col.1. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Ecclesiastical intelligence: preferments and appointments". Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser. British Newspaper Archive. 21 August 1886. p. 16 col.7. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "NY Times". The New York Times. 27 April 1905. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ a b "History notes". stursula.ch. St Ursula's Church Berne, Switzerland. 17 February 2019. Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Village hospitals". Evening Mail. British Newspaper Archive. 3 January 1866. p. 4 col.4. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Confirmation at the Parish Church". Faringdon Advertiser and Vale of the White Horse Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 15 March 1884. p. 4 col.5. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Church news". Church Times. No. 1229. 13 August 1886. p. 610. ISSN 0009-658X. Retrieved 20 September 2020 – via UK Press Online archives.

- ^ "Church news". Church Times. No. 1230. 20 August 1886. p. 626. ISSN 0009-658X. Retrieved 20 September 2020 – via UK Press Online archives.

- ^ a b "The Anglican Church in Europe". Home News for India, China and the Colonies. British Newspaper Archive. 21 October 1892. p. 9 col.1. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ a b c "Bishop Wilkinson". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. British Newspaper Archive. 24 October 1914. p. 4 col.3. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ "Bradford". Taunton Courier, and Western Advertiser. British Newspaper Archive. 18 January 1911. p. 5 col.3. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Wilkinson, Thomas Edward (1906). Twenty Years of Continental Work and Travel. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. ISBN 978-1-376-67037-0. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ "The sale of Glastonbury Abbey, the missionary college suggestion". Central Somerset Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 17 November 1906. p. 4 col.5. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Glastonbury Abbey (1345447)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ O'Connor, J.J.; Robertson, E.F. (July 2008). "John William Colenso". mathshistoryst-andrews.ac.uk. University of St Andrews Scotland. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Their lessons for the Church of England". Norfolk Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 3 October 1907. p. 3 col.3. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Our history". standrewsbh.org.uk. St Andrews. 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Venn, John (1954). Alumni Cantabrigienses: A Biographical List of All Known Students, Graduates and Holders of Office at the University of Cambridge, from the Earliest Times to 1900. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-03616-0.