Edward Oxford

Edward Oxford | |

|---|---|

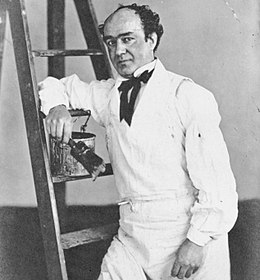

Oxford, c. 1857 | |

| Born | 19 April 1822 Birmingham, Warwickshire, England |

| Died | 23 April 1900 (aged 78) Melbourne, Victoria, Australia |

| Known for | Attempted regicide of Queen Victoria |

| Criminal charge | High treason |

| Spouse |

Jane Bowen (m. 1881) |

Edward Oxford (19 April 1822 – 23 April 1900) was an English man who attempted to assassinate Queen Victoria in 1840. He was the first of seven unconnected people who tried to kill her between 1840 and 1882. Born and raised in Birmingham, he showed erratic behaviour which was sometimes threatening or violent. He had a series of jobs in pubs, all of which he lost because of his conduct. In 1840, shortly after being dismissed from yet another pub, he purchased two pistols and fired twice at Queen Victoria and her husband, Prince Albert. No-one was hurt.

Oxford was arrested and charged with high treason. A jury found him not guilty by reason of insanity and he was detained indefinitely at Her Majesty's pleasure at the two State Criminal Lunatic Asylums: first at Bethlem Royal Hospital and then, after 1864, Broadmoor Hospital. Visitors and staff did not consider him insane.

In 1867 Oxford was given the offer of release if he relocated to a British colony; he accepted and settled in Melbourne, Australia, under the new name "John Freeman". He worked as a decorator, married and became a respected figure at his local church. He began writing stories on the seedier aspects of Melbourne life for The Argus, which were published under the pseudonym "Liber". He later published a book, Lights and Shadows of Melbourne Life, which looks at both the wealthy and seamy parts of Melbourne.

Oxford's trial, and the later M'Naghten case led to an overhaul of the law on criminal insanity in England. In January 1843 Daniel M'Naghten murdered Edward Drummond—the private secretary to the Prime Minister—mistaking him for the Prime Minister, Robert Peel. Like Oxford, M'Naghten was also found not guilty on the grounds of insanity. The cases of Oxford and M'Naghten prompted the judiciary to frame the M'Naghten rules on instructions to be given to a jury for a defence of insanity.

Biography

[edit]Early life: 1822–1840

[edit]Edward Oxford was born in Birmingham, England, on 19 April 1822. His parents were George Oxford and his wife Hannah (née Marklew). The couple met in Birmingham's Hope and Anchor tavern, which was owned by Hannah's parents; George was a goldsmith and chaser and earned an average of £20 a week.[1][2][a] Edward was the third of the couple's seven children, although only four survived until 1829.[4] According to Jenny Sinclair, Edward's biographer, George's behaviour was erratic when he was younger and he was an "impulsive and a heavy drinker" by the time he was twenty. George and Hannah's relationship was abusive and George, at various times, threatened, starved, beat and threw a pot at Hannah, which left her with a scar.[5][6] George died in June 1829 when Edward was seven years old, by which time the family were living in London.[5]

On her husband's death, Hannah returned to Birmingham with Oxford before they moved back to London, where Hannah initially became a housekeeper for a banker.[7] According to the historian Paul Murphy, Oxford's behaviour as a youth was erratic and he had "fits of unprovoked, maniacal laughter"; this behaviour caused the failure of two food outlets his mother was then operating.[8] By 1831 Oxford was being cared for by his maternal grandfather in Birmingham and had begun working for a tailor.[9] When he was fourteen Oxford was sent to work at the King's Head, an aunt's pub in Hounslow, then part of Middlesex. His erratic behaviour continued: he turned off the gaslights when the pub was full of customers, assaulted someone with a large chisel or screwdriver—for which he was found guilty of assault and fined £1 10s 6d—and fired an arrow at another boy, injuring him.[10][b]

When the King's Head closed eleven months after his arrival, Oxford took a series of jobs in other London pubs.[11] He was dismissed from the Shepherd and Flock in Marylebone High Street after he attacked a colleague with a knife;[5] he lasted only a few months at the Hat and Flowers in St Luke's, and four months at the Hog in the Pound in Oxford Street, where he was on a salary of £20 a year.[11][12][c] He was sacked on 30 April and given his quarter's salary of £5.[13][d] After leaving the Hog in the Pound, Oxford moved in with his mother and sister at 6 West Place, West Square, Lambeth.[14][15]

Assassination attempt: April to June 1840

[edit]Three days after he lost his job, Oxford went to a shop in Blackfriars Road and spent £2 on two pistols and a powder flask.[16][e] He practised in his back garden, firing the guns charged with powder, but probably not loaded with shot;[17] he also visited a shooting gallery in Leicester Square, where he practised with their guns.[18] About a week after he moved in, he hit his mother for no apparent reason and threatened her with a pistol; she returned to Birmingham shortly afterwards, leaving Oxford in Lambeth with his sister Susannah and her husband William Phelps.[13][19][f] Over the next month Oxford invented a fictional organisation, Young England, a pseudo-military revolutionary group of which he was the leader.[20][21] He drew up a document of eleven rules, signed by the fictitious A. W. Smith; the first of these was "That every member shall be provided with a brace of pistols, a sword, a rifle and a dagger; the two latter to be kept at the committee room".[22] He drew up a list of principal members—all fictitious—into ranks of president, council members, generals, captains and lieutenants, and each rank had a "mark of distinction" to signify their position, such as a black bow (for the president) or a large white cockade (for council members).[23][g]

On 10 June 1840—the eleventh anniversary of George Oxford's death—Oxford walked to Constitution Hill, near Buckingham Palace, and waited for two hours; the royal couple were known to take an evening drive most days and groups of onlookers were common at that time. At around 6:00 pm Queen Victoria—four months pregnant with her first child, Victoria, the Princess Royal—and Prince Albert left the palace in their drosky, an open-topped horse-drawn carriage, accompanied by the postillions (the drivers mounted on horses) and two outriders.[24][25] The carriage passed a group of spectators by the gates to the palace and travelled along Constitution Hill; as it came within a couple of metres of Oxford, he drew out his first pistol and fired.[26] His shot missed: he said "I have got another",[27] drew his second pistol and fired that after the carriage. The carriage continued on to the house of Victoria's mother, Victoria, Duchess of Kent.[26][28] The Queen recorded in her diary:

I was deafened by the loud report of a pistol, and our carriage involuntarily stopped. Albert was sitting on my right. We looked round and saw a little man on the footpath, with his arms folded over his breast, a pistol in each hand, and before half a minute elapsed, I saw him aim at me with another pistol. I ducked my head, and another shot, equally loud, instantly followed; we looked round and saw that the man had been quickly surrounded and seized. Albert directly ordered the postillion to drive on as if nothing had happened, to Mama's house. Just before the second shot was fired and as the man took aim, or rather more while he fired, dear Albert turned towards me, squeezing my hand, exclaiming "My God! Don't be alarmed". I assured him I was not the least frightened, which was the case.[29]

Onlookers apprehended Oxford—some shouting "Kill him!"—and disarmed him; he did not struggle.[30] One of the first people to reach him, Albert Lowe, took both pistols. Holding the guns, he was mistaken for the assassin, seized and beaten. Oxford, annoyed at the attention being on someone else, admitted his culpability by saying "I am the man who fired; it was me".[31][32][h] Police soon arrived and arrested Oxford, who was taken into custody at the nearest police station, in Gardner's Lane.[34] According to Murphy, the decision by Victoria and Albert to continue their journey rather than return to the palace "turned near-tragedy into overwhelmingly personal triumph".[30] They returned to the palace an hour later, by which time a crowd had gathered, greeting the couple with cheers.[35][36] Over the next hours and days they made themselves publicly visible, showing the public that the royal couple trusted them.[30]

On the way to the police station, Oxford hinted that he had not acted alone, and once he was in custody, his rooms were searched and the information about Young England was discovered. Questioned by the Earl of Uxbridge—the Lord Chamberlain, the most senior officer in the royal household—Oxford again spread his tale of the conspiracy of which he was part.[37] Subsequent newspaper speculation suggested the organisation may be connected to the Chartists—the working-class movement pressing for self-determination and democratic reforms—the Germans or a faction of the Orange Order within the Tories.[38] The reference to Germany was concerning to some in Britain, as if Victoria had been assassinated, she would have been succeeded on the British throne by Ernest Augustus, king of the German state of Hanover. Murphy considers him "without question the most wicked, the most feared, and the most reviled of George III's sons", and observes that the reference to Augustus would have been "chilling to any British reader".[39]

Although there was some initial doubt about whether his pistols were loaded, once Oxford was at the police station he was asked, and, in front of several witnesses, he admitted that they had been. On all subsequent occasions, he said they were only charged with powder but not with shot.[40] Several people visited the police station to see Oxford, including Charles Murray, the Master of the Household; Fox Maule, the Under-Secretary of State for the Home Department; and Henry Cadogan, 4th Earl Cadogan, a member of Her Majesty's Diplomatic Service.[41] Among those summoned to the station was a magistrate from the Queen Square police court; he charged Oxford with "maliciously and unlawfully discharging two pistols at the Queen and Prince Albert".[34] A charge of high treason was added before the trial started. This carried a possible punishment of hanging, drawing and quartering.[42]

The following morning Oxford was taken from the police station to offices of the Home Department in Whitehall where he was interrogated by the Marquess of Normanby, the Home Secretary. Oxford said to him:

A great many witnesses [are] against me. Some say I shot with my left, others with my right. They vary as to the distance. After I had fired the first pistol, Prince Albert got up, as if he would jump out of the coach, and sat down again, as if he thought better of it. Then I fired the second pistol. That is all I have to say at present.[43]

That afternoon Oxford was questioned by the Privy Council, although all he would admit to was firing the pistols.[44][45] That evening he was sent to Newgate Prison to await trial.[45] While in Newgate, Oxford was examined by several doctors specialising or having a professional interest in mental illness. These included the pathologist Thomas Hodgkin; John Conolly, the head of Middlesex County Asylum at Hanwell; and the surgeon James Fernandez Clarke, who accompanied as the Oxfords' family doctor.[46][47]

Trial: July 1840

[edit]

The trial took place from 9 to 11 July 1840 at the Old Bailey, central London. Three judges presided: Lord Denman, Baron Alderson and John Patteson.[48][49] The prosecution was led by Sir John Campbell, the Attorney General, and Sir Thomas Wilde, the Solicitor General.[50] Oxford was represented by Sidney Taylor and William Henry Bodkin.[51][47] Taylor was a member of an organisation that opposed the death penalty, and they agreed to pay Taylor's fees as long as he was the lead barrister for the defence.[47]

Campbell opened the prosecution by recounting the history of events and details of Oxford's purchase of the pistols and his practising in shooting galleries; he also referred to Young England and read out the rules and regulations and some of the correspondence, but made no comment on them.[52][53] According to the criminologist Richard Moran, it was strange that Campbell spent nearly an hour reading through the Young England information, but made no comment as to its significance.[52] Based on the transcript of the trial, Moran considers "it is difficult to ascertain if Campbell meant to ridicule Oxford by the introduction of this material, or if he had some other, undisclosed purpose."[54]

Taylor provided two lines of defence for Oxford: the first was that the pistols were not loaded; the second that Oxford was insane.[55] According to Murphy, the biggest weakness of the government's case was that they could not prove that the pistols were loaded.[56] When questioned, a policeman informed the court that no bullet had been found, despite an extensive search of the area that included sweeping up the dust and dirt and putting it through a sieve; nearby walls were examined for bullet holes, but none had been found.[57] Although when he was first questioned Oxford had said he had loaded the pistols, the arresting officer said he may have misremembered Oxford's exact words;[58] Taylor passed off Oxford's initial claim as being a vainglorious boast.[59]

After discussion of the evidence about the pistols, Oxford's sanity was examined.[60] Several friends and family members all gave evidence that Oxford, his father and grandfather had exhibited unusual behaviour.[61] Their evidence was followed by that of the doctors who had attended Oxford at Newgate; all reported that they considered he was mentally disturbed.[62] Based on his interview, Conolly surmised that Oxford showed:

... an occasional appearance of acuteness, but a total inability to reason—a singular insensibility as regards the affections – an apparent incapacity to comprehend moral obligations, to distinguish right from wrong – an absolute insensibility to the heinousness of his offence, and to the peril of his situation—a total indifference to the issue of the trial; acquittal will give him no particular pleasure, and he seems unable to comprehend the alternative of his condemnation and execution; his offence, like that of other imbeciles who set fire to buildings, et cetera, without motive, except a vague pleasure in mischief—appears unable to conceive anything of future responsibility.[2][63]

Giving evidence, William Dingle Chowne, a lecturer on medical jurisprudence at Charing Cross Hospital, thought Oxford was not in control of his will; he explained that "a propensity to commit acts without an apparent or adequate motive under such circumstances is recognised as a particular species of insanity ... it has been called moral insanity".[2][63] Conolly reported that when he asked Oxford why he had shot at the queen, he answered "Oh, I might as well shoot at her as anybody else".[64][65] According to the archivist Patricia H. Allderidge "the singular pointlessness of it all paved the way for a defence of insanity against a capital charge".[61]

After the closing arguments had been made, the jury retired for 45 minutes to make their decision.[66] They concluded "We find the prisoner, Edward Oxford, guilty of discharging the contents of two pistols, but whether or not they were loaded with ball has not been satisfactorily proved to us, he being of unsound state of mind at the time."[67] The judge, unhappy with the non-standard nature of the decision, bade them retire again to reconsider; they returned an hour later to say Oxford was "guilty, being at the time insane". Denman clarified "You find him not guilty, or he was [guilty], but for his insanity".[68][69] Oxford, aged 18, was sentenced to be detained at Her Majesty's pleasure,[70] a verdict based on the Criminal Lunatics Act 1800 that allowed the state to incarcerate him for as long as it wished.[71][72]

Incarceration: 1840–1867

[edit]On 18 July 1840 Oxford was taken from Newgate to Bethlem Royal Hospital at St George's Fields, London.[73] Also known as Bedlam, the hospital was the first in the UK to specialise in mental illness.[74][75] One wing of the hospital was the State Criminal Lunatic Asylum, and those incarcerated there had committed crimes while judged to be insane.[76][77][i]

Little is known about Oxford's life in at the Bethlem Hospital.[73] From the time he arrived, the doctors considered him to be sane.[76][80] Conditions in the hospital were harsh and Oxford had to spend much of his time in one large room with violent prisoners; he was attacked with a chamber pot by one prisoner.[81][82] A visitor to the asylum in 1842 reported that Oxford spent his time drawing—his works "were uncommonly well executed, and evinced a natural talent for the art"—and reading.[83] He taught himself to read French, but bemoaned the lack of opportunity to practise his pronunciation; when asked about his mental state, he acknowledged that he was there because others had thought him insane, but said he "was really very far from being mad".[73][83]

A report undertaken by the Home Office into the hospital's criminal inmates found Oxford to be "healthy and sane".[69] The case notes on him in February 1854—probably by Bethlem's superintendent, William Charles Hood—described how Oxford "from the statements of the attendants and those associated with him he appears to have conducted himself with great propriety at all times".[84][85] The notes recorded that Oxford spent much of the time learning: he had learned to speak, or had knowledge of, French, German, Italian, Spanish, Latin and Greek.[86] He also learned to knit and play the violin; he became a chess player and a painter. As the historian Barry Smith notes, "Bedlam was his university".[87] Oxford's case notes stated that "With regard to his crime he now laments the act which probably originated in a feeling of excessive vanity and a desire to become notorious if he could not be celebrated".[85]

Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum replaced Bethlem Hospital as Britain's main criminal asylum in 1864 and Oxford, along with several other patients, was transferred to the new institution that April.[85][88] He was in good physical shape, although suffering from constipation and urethritis.[84] A journalist from The Times visited Broadmoor in January 1865, and described Oxford as "a fat, elderly man" leading a group of inmates who were decorating the premises. The journalist reported that Oxford "has now perfectly recovered his sanity, and is the most orderly, most useful and most trusted of all the inmates".[89] It was also reported that as inmates were paid a small sum for working, he had managed to save between £50 and £60,[89][j] although Sinclair states Oxford had savings of £6 17s when he left Broadmoor.[90][k]

Soon after his arrival at Broadmoor, Oxford appealed for release to Sir George Grey, the Home Secretary, with the support of the chairman of Broadmoor, the deputy superintendent, the hospital's resident doctor and the prison surgeon. Grey ignored the request. In 1867 Gathorne Hardy, who had taken over as Home Secretary, wrote to the governor of Broadmoor, asking for a report on Oxford; he received a certificate attesting to Oxford's sanity. Hardy offered Oxford release, conditional on his emigration to the colonies, never to return to Britain.[91][84]

Mr. Hardy requests that it may be distinctly explained to Oxford that he is released upon the condition of his quitting the United Kingdom immediately and of his never returning to it, and that should he at any time violate this condition he will be apprehended and placed in confinement for the rest of his life.

— Letter to Broadmoor from a civil servant, 1867[90]

Oxford accepted, and on 22 October 1867, aged 45 and after 27 years of confinement, he was released. He was photographed and his image was distributed to police stations to ensure he would be recognised if he returned.[92]

Australia: 1867–1900

[edit]

On leaving Broadmoor, Oxford wrote to one of the stewards at Bethlem,[l] George Henry Haydon, thanking him for "all of the kindness I have received at your hands";[94] on the question of his emigration, he told Haydon:

In leaving England forever I do what is certainly the best, for a man who has once been in the grip of the law ... It makes no matter what his offence, or whether he has paid the full pound of flesh ten-times over, the taint clings to him like a leprosy, & makes men worse than himself affect airs of superiority over him. All that, at a distance, & where he is unknown, is prevented. He can then find his own level, by putting on the bold front necessary ... in the future no man shall say I am unworthy of the name of an Englishman.[95]

Oxford did not have enough money to cover the £25 fare to Australia, and the government refused to pay. Haydon gave him £43 18s—probably from several people, but Haydon was the main benefactor[m]—and Oxford was able to pay for his passage, buy new clothing and still have £22 left for his arrival in Australia. The berth was booked in the name John Freeman: Oxford's chosen name for his new life.[97][n] Oxford was escorted to Plymouth in late November and boarded the SV Suffolk; the ship set sail on 3 December 1867 and arrived in Melbourne on 7 February 1868.[95]

There is limited information about Oxford's first years in Australia and he does not appear in any official records for his first five years in the colony.[98] Sinclair identifies a "James Freeman" working as a painter in Melbourne between 1870 and 1879, which is possibly Oxford, but the first known reference to him was in 1873 when "John Freeman" was named in The Argus as a churchwarden at St James Old Cathedral, Melbourne.[99]

In 1874 Oxford joined the West Melbourne Mutual Improvement Society, an organisation Sinclair describes as being "aimed to improve their members' minds with debate, supplementing the push of the time to create public libraries and other institutions to illuminate the working man's world".[100] Oxford was vice-president of the society the following year and gave talks to the members.[101] He began writing on the seedier aspects of Melbourne life and had articles published in The Argus in 1874 under the pseudonym "Liber"—Latin for "free man". He continued writing for the newspaper, introducing its readership to the city's slums and its inhabitants, providing descriptions of the people and their lives.[101][102]

In May 1880 The Argus carried a story of a man they named as "John Oxford" who had previously attempted to shoot the queen. The man had been caught stealing a shirt and had spent a week in prison.[103] There were differences between "John Oxford" and Edward Oxford, including their heights and ages.[104] The historian Mark Stevens considers "John Oxford" was possibly John Francis, who had also attempted to assassinate Victoria, but who had been transported to Australia, rather than placed in an asylum.[105] Sinclair considers that "John Oxford" was unlikely to be Edward Oxford, but notes that during the time "John Oxford" was in prison, none of Edward's articles appeared in The Argus and he did not appear in the church records.[106]

In 1881 Oxford met and married Mrs Jane Bowen (née Tapping), an English woman who had emigrated to Australia, and had been married and widowed twice.[107][108] Oxford signed the marriage register as John Freeman and did not tell his wife of his former name or crime.[109]

In 1888 Oxford published Lights and Shadows of Melbourne Life, a factual work that provides sketches of life in both the wealthy and seamy parts of nineteenth-century Melbourne.[110] Some of the information came from the articles that he had written for The Argus.[111] He included chapters on the zoo and the racecourse and information on churches and markets. His first chapter was titled "What we Have in our Midst", and examines the city's slums, poverty and opium dens.[112][113] Oxford sent a copy to the former steward at Bethlem Hospital, Haydon, who had travelled through Melbourne in the 1840s and had written about the area. In the accompanying note, Oxford wrote "You are the only man in the world, besides myself, who could connect me with the book. ... Even my wife, the sharer of my joys and sorrows, is no wiser than the rest of the world."[114][115] Haydon and Oxford continued their correspondence until Haydon's death in November 1891.[116]

Oxford had continued with his work for the church. After serving as churchwarden in 1883 and 1885, he was the lay representative for St James Cathedral at the Anglican Church Assembly for the Diocese of Melbourne in 1887 and, in 1894, he was a pallbearer at the funeral of Hussey Burgh Macartney, the Dean of Melbourne. Oxford, as honorary secretary to the vestry of St James, wrote to The Argus to raise funds for a plaque for Macartney.[117]

On 23 April 1900, four days after his 78th birthday, Oxford died of apoplexy; he was buried in Melbourne General Cemetery.[118]

Historiography

[edit]Haydon's family kept the letters Oxford sent to Haydon. In the 1950s his descendants gave them to the National Library of Australia.[102][119][o] In 1987 Barry Smith came across the letters and published the article "Lights and Shadows in the Life of John Freeman", making public the connection between Oxford and Freeman.[120][121] Jenny Sinclair wrote a full-length biography of Oxford in 2012, A Walking Shadow: The Remarkable Double Life of Edward Oxford and then undertook a PhD on him, writing her thesis, "Lights and Shadows in Australian Historical Fiction" in 2019.[102][122] Sinclair considered that Freeman and Oxford were the same person, partly based on her observation that a photograph of Oxford taken at Bethlem Hospital shows a marked similarity to one taken of "Freeman" in 1888, when he was representing the church at the Melbourne Centennial Exhibition.[120]

Legacy

[edit]Later assassination attempts and the law

[edit]Six others tried to assassinate Victoria between 1840 and 1882, one of whom, John Francis, tried twice in May 1842.[123] After Francis's second effort, Oxford said to a warder at Bethlem Hospital "If only they had hanged me, the dear Queen would not have had all this bother".[124][p]

According to the historian Georgina Rychner, Oxford became connected with the insanity defence. The medico-legal question about criminal insanity continued through the rest of the nineteenth century.[126] The defence of insanity was used again in January 1843, when Daniel M'Naghten walked up behind Edward Drummond—the Prime Minister's private secretary—and shot him in the back, killing him.[q] M'Naghten later said that he thought the man was the Prime Minister, Robert Peel.[128] Following so soon after the acquittal of Oxford, Victoria was unhappy with the result and wrote to Peel in March 1843:[129]

The law may be perfect, but how is it that whenever a case for its application arises, it proves to be of no avail? We have seen the trials of Oxford and MacNaghten conducted by the ablest lawyers of the day—Lord Denman, Chief Justice Tindal, and Sir Wm. Follett, —and they allow and advise the Jury to pronounce the verdict of Not Guilty on account of Insanity,—whilst everybody is morally convinced that both malefactors were perfectly conscious and aware of what they did! It appears from this; that the force of the law is entirely put into the Judge's hands, and that it depends merely upon his charge whether the law is to be applied or not.[130]

The matter of the insanity defence was raised in the House of Lords, which put pressure on the government to clarify the matter. The government suggested the Lords should ask the judges of the Law Lords to provide clarification on the situation.[131] Fifteen judges reported back to the Lords and their answers formed the M'Naghten rules on instructions to be given to a jury for a defence of insanity.[132] These included the direction "to establish a defence on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under ... a defect of reason".[133]

When Arthur O'Connor was given a year's imprisonment and a birching after he fired a pistol at her in 1872, Victoria had her private secretary write to the Prime Minister to say "The Queen must say she is shocked at only one year's imprisonment considering how much she was alarmed at the time and she fully expects we shall have more of these things".[134] Ten years later Roderick Maclean shot at her at Windsor station before he was set upon by schoolboys from Eton College.[134] The verdict at his trial was not guilty on grounds of insanity. Victoria was angered by the verdict and complained to her private secretary Henry Ponsonby that "It is Oxford's case over again".[135] Ponsonby wrote to William Gladstone, the Prime Minister, passing on the Queen's thoughts:

Her Majesty thinks it worth consideration whether the law should not be amended. ...

Punishment deters not only sane men but also eccentric men, whose supposed involuntary acts are really produced by a diseased brain capable of being acted upon by external influence.

A knowledge that they would be protected by an acquittal on the grounds of insanity will encourage these men to commit desperate acts, while on the other hand certainty that they will not escape punishment will terrify them into a peaceful attitude – towards others.[136]

Portrayals and popular culture

[edit]

Shortly before his trial Oxford was visited by an Italian artist from Madame Tussauds. The artist took a plaster cast of Oxford's face and head,[138] and a waxwork of him was soon on display, advertised in the press.[139][140] The same year, the caricaturist John Leech drew a satire of Oxford, in which he "revived the iconography of the age of revolutions in portraying Oxford sporting a tricolour cockade, with a cap of liberty on his coat of arms", according to the political historian Gordon Pentland.[141] Both the cockade and cap were symbolic of the French Revolution.[142] Alluding to Oxford's fictitious society Young England, the wording below the image describes Oxford as "the patriotic imitator of Young France".[143]

The writer Charles Dickens took a close interest in the assassination attempt and subsequent trial, and thought Oxford "should have been smothered at birth", according to the Dickens scholar Clive Hurst.[144] The events took place while Dickens was writing Barnaby Rudge (published in serial form between February and November 1841). One of the book's characters, Sim Tappertit, was modelled on Oxford; Tappertit is described as a "vainglorious apprentice" by Murphy and a "sinister and darkly comical figure" by Hurst.[144][145] When The Old Curiosity Shop was published in serial form between April 1840 and February 1841, it included a drawing by Hablot Knight Browne, also known as "Phiz", that included an image of Oxford holding a pistol pointing at Victoria; papers titled "Young England" are in his jacket pocket.[137] In the mid 1840s the writer George W. M. Reynolds published the series The Mysteries of London, which includes Henry Holford, a pot-boy; this character was a combination of Oxford and the boy Jones—a teenager who broke into Buckingham Palace several times between 1838 and 1841.[146]

In 2010 the author Mark Hodder wrote The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack, a steampunk novel whose plot centres on one of Oxford's descendants—also called Edward Oxford—who travels back in time to assassinate Victoria, only to be thwarted by fictitious renderings of the explorer and writer Richard Francis Burton and the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne.[147] Oxford is also used as a character in David Morrell's 2015 novel, Inspector of the Dead; the book includes Young England as an assassins' conspiracy.[148]

Oxford's assassination attempt has been dramatised twice, firstly for the 2009 film The Young Victoria,[149] and then again in 2016 for the television series Victoria.[150] A BBC Radio history series in March 2023, Killing Victoria, included an episode on Oxford's attempt.[151]

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ £20 in 1822 is approximately equivalent to £2,300 in 2023, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[3]

- ^ £1 10s 6d in 1838 is approximately equivalent to £170 in 2023, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[3] His next job carried a salary of £20 a year, so £1 10s 6d was a not inconsiderable amount.[11]

- ^ £20 in 1840 is approximately equivalent to £2,280 in 2023, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[3]

- ^ £5 in 1840 is approximately equivalent to £570 in 2023, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[3]

- ^ £2 in 1840 is the approximate equivalent to £230 in 2023, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[3]

- ^ In the later case against Oxford, Hannah's testimony was that "he made my nose bleed by a blow from his fist—I was playing with him and turned round, and he hit me on the nose—that was not in the course of the play—it was after—he turned round suddenly as he was going through the door, and struck at me—it hurt me very much".[2]

- ^ The other ranks and their marks were: generals (three red bows), captains (two red bows) and lieutenants (one red bow).[23]

- ^ Sinclair notes that there were several variants of his confession recorded, including "It was me that did it", "It was I" and "I did it".[33] Stevens reports the words were "It was I, it was me that did it".[31]

- ^ The word "bedlam", meaning confusion or uproar, derives from the Bethlem Hospital; it entered the English language in its figurative sense early in the 16th century.[78][79]

- ^ £50 to £60 in 1865 equates to approximately £6,000 to £7,000 in 2023, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[3]

- ^ £6 17s equates to approximately £679 in 2023, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[3]

- ^ Stewards were, along with porters and matrons, the lower officers at the hospital, although they were ranked above nurses, attendants and keepers, all of whom were afforded a similar status to domestic servants.[93]

- ^ £43 was about 10 per cent of Haydon's annual salary.[96]

- ^ £25 in 1867 equates to approximately £2,800 in 2023; £43 18s in 1838 equates to approximately £4,990 the same year, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[3]

- ^ Haydon's letters to Oxford were lost.[116]

- ^ This is also recorded as Oxford saying that if they had hanged him "there would have been no more shooting at the Queen".[125]

- ^ M'Naghten's name was rendered in multiple other spellings in different sources, including McNaghten, McNaghton, Macnaghton, Macnaghten, Macnaughten, Macnaughton, McNaughton, McNaughten and others.[127]

References

[edit]- ^ Sinclair 2012, pp. 13, 14–15.

- ^ a b c d "Edward Oxford: Royal Offences: Treason". Old Bailey Proceedings Online.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Clark 2023.

- ^ Charles 2014, p. 22; Stevens 2013, pp. 35–36; Sinclair 2012, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Charles 2014, p. 22.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Charles 2014, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Murphy 2013, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 18.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 19; Charles 2014, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Murphy 2013, p. 34.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, pp. 19–21.

- ^ a b Murphy 2013, p. 36.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 23.

- ^ Charles 2014, p. 25.

- ^ Charles 2014, p. 9.

- ^ Murphy 2013, p. 41.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 1.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Murphy 2013, pp. 5, 9, 34.

- ^ Charles 2014, p. 27.

- ^ a b Charles 2014, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Charles 2014, p. 11; Stevens 2013, p. 37; Sinclair 2012, pp. 29–30.

- ^ "Edward Oxford (1822–1900)". Berkshire Record Office; Queen Victoria. "Journal Entry: Wednesday 10th June 1840", p. 274.

- ^ a b Sinclair 2012, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Walker 1968, p. 186.

- ^ Queen Victoria. "Journal Entry: Wednesday 10th June 1840", p. 275; "Atrocious Attempt to Assassinate the Queen and Prince Albert". The Times.

- ^ Queen Victoria. "Journal Entry: Wednesday 10th June 1840", pp. 274–275.

- ^ a b c Murphy 2013, p. 56.

- ^ a b Stevens 2013, p. 37.

- ^ Murphy 2013, p. 59.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 31.

- ^ a b Sinclair 2012, p. 33.

- ^ "Atrocious Attempt to Assassinate the Queen and Prince Albert". The Times.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 32.

- ^ Murphy 2013, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Charles 2014, p. 30.

- ^ Murphy 2013, p. 40.

- ^ Murphy 2013, p. 60.

- ^ Charles 2014, p. 26.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, pp. 33, 38.

- ^ Moran 1986, p. 172.

- ^ Charles 2014, p. 28.

- ^ a b Sinclair 2012, p. 35.

- ^ Stevens 2013, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b c Freemon 2001, p. 361.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 47.

- ^ Wallis 1892, p. 498.

- ^ Moran 1986, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 45.

- ^ a b Moran 1986, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Wallis 1892, pp. 500–506.

- ^ Moran 1986, p. 176.

- ^ Poole 2018, p. 184.

- ^ Murphy 2013, p. 109.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 53.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 54.

- ^ Murphy 2013, p. 110.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 55.

- ^ a b Allderidge 1974, p. 52.

- ^ Stevens 2013, p. 39.

- ^ a b Jones 2017, p. 268.

- ^ Eigen 2003, p. 106.

- ^ Stevens 2013, p. 38.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 185.

- ^ Charles 2014, p. 32.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 60.

- ^ a b Poole 2018, p. 186.

- ^ Wallis 1892, p. 555.

- ^ Murphy 2013, p. 122.

- ^ Moran 1986, pp. 173–175.

- ^ a b c Moran 1986, p. 186.

- ^ Arnold 2008, p. 2.

- ^ "About Bethlem". Bethlem Museum of the Mind.

- ^ a b "In the Spotlight: Edward Oxford". Bethlem Museum of the Mind.

- ^ Andrews 1997, pp. 96–97.

- ^ "Bedlam". Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ Andrews 1997, p. 1.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 68.

- ^ Smith 1981, p. 87.

- ^ Smith 1987, p. 467.

- ^ a b "Edward Oxford in Bethlehem". The Times.

- ^ a b c "Edward Oxford (1822–1900)". Berkshire Record Office.

- ^ a b c Moran 1986, p. 188.

- ^ Murphy 2013, p. 509.

- ^ Smith 1987, p. 468.

- ^ Charles 2014, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b "A Visit to the Criminal Lunatic Asylum". The Times.

- ^ a b Sinclair 2012, p. 82.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Moran 1986, p. 188; Sinclair 2012, p. 81; Charles 2014, p. 36.

- ^ Russell 1997, p. 39.

- ^ Charles 2014, p. 36.

- ^ a b Charles 2014, p. 37.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 83.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 105.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b Sinclair 2012, p. 109.

- ^ a b c Webb 2012.

- ^ Stevens 2013, p. 42.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 112.

- ^ Stevens 2013, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 114.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Murphy 2013, p. 510.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 116.

- ^ Charles 2014, p. 38.

- ^ Freeman 1888, p. viii.

- ^ Freeman 1888, p. v.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, pp. 130, 133.

- ^ Smith 1987, p. 470.

- ^ Murphy 2013, p. 511.

- ^ a b Sinclair 2012, p. 152.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, pp. 118, 155.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, p. 159.

- ^ Sinclair 2012, pp. 152, 169.

- ^ a b Sinclair 2019, p. 93.

- ^ Rychner 2018, p. 29.

- ^ Sinclair 2019, p. 1.

- ^ Murphy 2013, p. ix.

- ^ Turner 1990, p. 224.

- ^ Aitken & Aitken 2010, p. 55.

- ^ Rychner 2018, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Diamond 1977, pp. 88–89.

- ^ West & Walk 1977, p. 1.

- ^ Murphy 2013, p. 249.

- ^ Queen Victoria 1963, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Brougham 1843; Ormrod 1977, p. 10; Kaplan 2023, p. 20.

- ^ Prosono 2003, p. 19.

- ^ Garvey 2020, p. 211.

- ^ a b Walker 1968, p. 188.

- ^ Murphy 2013, pp. 480–481.

- ^ Walker 1968, p. 189.

- ^ a b Murphy 2013, p. 209.

- ^ Murphy 2013, p. 97.

- ^ "The Lunatic Edward Oxford". City Chronicle.

- ^ "The Lunatic Oxford". The Times.

- ^ Pentland 2023, p. 432.

- ^ Dwyer 2007, p. 96.

- ^ "The Regicide Pot Boy". The British Museum.

- ^ a b Hurst 2003, p. 672.

- ^ Murphy 2013, p. 129.

- ^ Pentland 2023, pp. 435–436.

- ^ Lalumière 2011.

- ^ "Fiction Reviews". Publisher's Weekly Review.

- ^ von Tunzelmann 2009.

- ^ Pepper 2016.

- ^ "Killing Victoria. Episode One: The Monster". BBC Genome.

Sources

[edit]Books

[edit]- Andrews, Jonathan (1997). The History of Bethlem. London: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-4150-1773-2.

- Arnold, Catharine (2008). Bedlam: London and its Mad. London: Pocket Books. ISBN 978-1-8498-3552-7.

- Charles, Barrie (2014). The Lucky Queen: The Eight Assassination Attempts on Queen Victoria. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-4369-4.

- Diamond, Bernard L. (1977). "On the Spelling of Daniel M'Naghten's Name". In West, Donald; Walk, Alexander (eds.). Daniel McNaughton: his Trial and the Aftermath. Ashford, Kent: Headley for the "British Journal of Psychiatry". pp. 86–90. ISBN 978-0-902241-01-5.

- Dwyer, Philip G. (2007). Napoleon: the Path to Power, 1769-1799. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-7475-7490-3.

- Eigen, Joel Peter (2003). Unconscious Crime: Mental Absence and Criminal Responsibility in Victorian London. Baltimore, MA: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7428-4.

- Freeman, John (1888). Lights and Shadows of Melbourne Life. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington.

- Garvey, Stephen P. (2020). Guilty Acts, Guilty Minds. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1909-2432-4.

- Hurst, Clive (2003). "Historical Sources and Contemporary Contexts". In Dickens, Charles (ed.). Barnaby Rudge. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 667–672. ISBN 978-0-1995-3820-1.

- Murphy, Paul Thomas (2013). Shooting Victoria: Madness, Mayhem and the Rebirth of the British Monarchy. New York: Pegasus Books. ISBN 978-1-6059-8503-9.

- Ormrod, Roger (1977). "The McNaughton case and its predecessors". In West, Donald; Walk, Alexander (eds.). Daniel McNaughton: his Trial and the Aftermath. Ashford, Kent: Headley for The British Journal of Psychiatry. pp. 4–11. ISBN 978-0-9022-4101-5.

- Poole, Steve (2018). The Politics of Regicide in England 1760-1850: Troublesome Subjects. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1-5261-3061-7.

- Prosono, Marvin (2003). "History of Forensic Psychiatry". In Rosner, Richard (ed.). Principles and Practice of Forensic Psychiatry (2nd ed.). London: Arnold. ISBN 978-0-3408-0664-7.

- Queen Victoria (1963). Raymond, John (ed.). Early Letters. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 494119.

- Russell, David (1997). Scenes from Bedlam: a History of Caring for the Mentally Disordered at Bethlem Royal Hospital and the Maudsley. London: Baillière Tindall. ISBN 978-1-873853-39-9.

- Sinclair, Jenny (2012). A Walking Shadow: The Remarkable Double Life of Edward Oxford. New York: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9872-3909-9.

- Smith, Roger (1981). Trial by Medicine: Insanity and Responsibility in Victorian Trials. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-8522-4407-4.

- Stevens, Mark (2013). Broadmoor Revealed: Victorian Crime and the Lunatic Asylum (Kindle ed.). Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-7834-6236-0.

- Walker, Nigel (1968). Crime and Insanity in England. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-85224-228-5.

- Wallis, John E. P. (1892). Reports of State Trials. Vol. IV, 1839 to 1843. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 953057943.

- West, Donald; Walk, Alexander (1977). Daniel McNaughton: his Trial and the Aftermath. Ashford, Kent: Headley for The British Journal of Psychiatry. ISBN 978-0-9022-4101-5.

Journals and magazines

[edit]- Aitken, Robert; Aitken, Marilyn (Summer 2010). "The M'Naghten Case: The Queen Was Not Amused". Litigation. 36 (4): 53–60. JSTOR 25801820.

- Allderidge, Patricia H (September 1974). "Papers: Criminal Insanity: Bethlem to Broadmoor". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 67 (9): 897–904. doi:10.1177/003591577406700932.

- "Fiction Reviews". Publisher's Weekly Review. Vol. 262, no. 2. 12 January 2015.

- Freemon, Frank R. (September 2001). "The Origin of the Medical Expert Witness: The Insanity of Edward Oxford". Journal of Legal Medicine. 22 (3): 349–374. doi:10.1080/01947640152596434. PMID 11602941. S2CID 71827199.

- Jones, David W. (September 2017). "Moral Insanity and Psychological Disorder: the Hybrid Roots of Psychiatry". History of Psychiatry. 28 (3): 263–279. doi:10.1177/0957154X17702316. PMC 5546420. PMID 28391708.

- Kaplan, Robert M. (20 January 2023). "Daniel M'Naghten: The Man Who Changed the Law on Insanity". Psychiatric Times. 40 (1): 19–20.

- Moran, Richard (January 1986). "The Punitive Uses of the Insanity Defense: The Trial for Treason of Edward Oxford (1840)". International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 9 (2): 171–190. doi:10.1016/0160-2527(86)90045-2. PMID 3542856.

- Pentland, Gordon (April 2023). "'An Offence New in Its Kind': Responses to Assassination Attempts on British Royalty, 1800–1900". Journal of British Studies. 62 (2): 418–444. doi:10.1017/jbr.2022.177.

- Rychner, Georgina (2018). "Temporary Fits, Animal Passions: Insanity in Victorian Capital Trials, 1890–1935". Health and History. 20 (1): 28–51. doi:10.5401/healthhist.20.1.0028. ISSN 1442-1771. JSTOR 10.5401/healthhist.20.1.0028. S2CID 80995712.

- Smith, F. B. (1987). "Lights and Shadows in the Life of John Freeman". Victorian Studies. 30 (4): 459–473. ISSN 0042-5222. JSTOR 3828160.

- Turner, Trevor (April 1990). "Erotomania and Queen Victoria: or Love Among the Assassins?". Psychiatric Bulletin. 14 (4): 224–227. doi:10.1192/pb.14.4.224.

News

[edit]- "Atrocious Attempt to Assassinate the Queen and Prince Albert". The Times. 11 June 1840. p. 4.

- "A Visit to the Criminal Lunatic Asylum". The Times. 13 January 1865. p. 10.

- "Edward Oxford in Bethlehem". The Times. 28 February 1843. p. 6.

- Lalumière, Claude (9 January 2011). "Sublimely strange sci-fi". Edmonton Journal. p. B3.

- "The Lunatic Edward Oxford". City Chronicle. 15 September 1840. p. 8.

- "The Lunatic Oxford". The Times. 21 September 1840. p. 1.

- Pepper, Penny (10 October 2016). "My 'insane' Uncle Ed tried to kill Queen Victoria – he was treated with kindness". The Guardian.

- von Tunzelmann, Alex (5 March 2009). "The Young Victoria: less chess, more Hungry Hungry Hippos". The Guardian.

- Webb, Carolyn (18 December 2012). "From would-be royal assassin to pillar of society". The Age. p. 3. Archived from the original on 7 December 2022.

Websites

[edit]- "About Bethlem". Bethlem Museum of the Mind. Archived from the original on 28 July 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- "Bedlam". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OED/1101861163. Retrieved 29 July 2023. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Clark, Gregory (2023). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- "Edward Oxford (1822–1900)" (PDF). Berkshire Record Office. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- "Edward Oxford: Royal Offences: Treason". Old Bailey Proceedings Online. July 1840. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- "In the Spotlight: Edward Oxford". Bethlem Museum of the Mind. Archived from the original on 12 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- "Killing Victoria. Episode One: The Monster". BBC Genome. 20 March 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- Queen Victoria. "Journal Entry: Wednesday 10th June 1840". Queen Victoria's Journals. Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- "The Regicide Pot Boy". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 5 July 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

Others

[edit]- Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux (6 March 1843). "Insanity And Crime". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Lords. col. 289–290.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Sinclair, Jenny (2019). Lights and Shadows in Australian Historical Fiction: how Does Historical Fiction Deal with how Australia Comes to Know its Past? (PhD thesis). University of Melbourne.

External links

[edit]- Freeman, John (1862), Papers of John Freeman, 1862–1889, retrieved 11 September 2023 at the National Library of Australia

- Biography from Tarlton Law Library

- John Freeman at Find a Grave

- 1822 births

- 1840 crimes in the United Kingdom

- 19th-century Australian writers

- 1900 deaths

- British emigrants to the Colony of Victoria

- English emigrants to colonial Australia

- Failed regicides

- Failed assassins

- People acquitted by reason of insanity

- People acquitted of treason

- People detained at Broadmoor Hospital

- People detained in hospitals in the United Kingdom

- People from Birmingham, West Midlands

- Queen Victoria