Economic policy of the Narendra Modi government

The economic policies of the Narendra Modi government, also known as Modinomics, focused on privatization and liberalization of the economy, based on a neoliberal framework.[1][2] Modi liberalized India's foreign direct investment policies, allowing more foreign investment in several industries, including in defense and the railways.[3][4][5] Modi liberalised India's foreign direct investment policies, allowing more foreign investment in several industries, including defence and railways Other proposed reforms included making the forming of unions more difficult for workers, and making recruitment and dismissal easier for employers. In 2021–22, the foreign direct investment (FDI) in India was $82 billion. India's gross domestic savings rate stood at 29.3% of GDP in 2022.[6]

Labour reform

[edit]Other reforms included removing many of the country's labor laws. Some scholars alleged said labour reforms were made to make it harder for workers to form unions and easier for employers to hire and fire them.[citation needed]

These reforms met with support from institutions such as the World Bank, but opposition from some scholars within the country. The labor laws also drew strong opposition from unions: on 2 September 2015, eleven of the country's largest unions went on strike, including one affiliated with the BJP. The strike was estimated to have cost the economy $3.7 billion.[7][8]

The Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh, a constituent of the Sangh Parivar, stated that the reforms would hurt laborers by making it easier for corporations to exploit them.[9]

Economy

[edit]In his first budget, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley promised to gradually reduce the budgetary deficit from 4.1% to 3% over two years and to divest from shares in public banks.[10]

Over Modi's first year in office, the Indian GDP grew at a rate of 7.5%,[11] making India the fastest-growing economy in the world. For this the basis was a revised formula introduced a year after he took office, which surprised a lot of economists.[12]

However, this rate of growth had fallen significantly to 6.1%, by his third year in office.[13] This fall has been blamed on the exercise of demonetisation of currency.

In July 2014, Modi refused to sign a trade agreement that would permit the World Trade Organization to implement a deal agreed in Bali, citing that agreement will lead to "lack of protection to Indian farmers and the needs of food security" and "Lack of bargaining power".[14] The addition to Indian airports grew by 23 percent in 2016 while the airfares dropped by over 25 percent.[15]

Over the first four years of Modi's premiership, India's GDP grew at an average rate of 7.23%, higher than the rate of 6.39% under the previous government.[16]

The level of income inequality increased,[17] while an internal government report said that in 2017, unemployment had increased to its highest level in 45 years.[18]

The loss of jobs was attributed to the 2016 demonetisation, and to the effects of the Goods and Services Tax.[19][20] The last year of Modi's first term didn't see much economic development and focused on the policies of Defence and on the basic formula of Hindutva.

His government focused on pension facilities for old-age group people and depressed sections of society.[21] The economic growth rate in 2018-19 was recorded to be 6.1%, which was lower than the average rate of the first four years of premiership.[22]

The fall in the growth rate was again attributed to the 2016 demonetisation and to the effects of the GST[23] on the economy.

Make in India

[edit]

In September 2014, Modi introduced the Make in India initiative to encourage foreign companies to manufacture products in India, with the goal of turning India into a global manufacturing hub.[24] Supporters of economic liberalisation supported the initiative, while critics argued it would allow foreign corporations to capture a greater share of the Indian market. "Make in India" had three stated objectives:

- to increase the manufacturing sector's growth rate to 12-14% per annum

- to create 100 million additional manufacturing jobs in the economy by 2022

- to ensure that the manufacturing sector's contribution to GDP is increased to 25% by 2022 (later revised to 2025).

Healthcare

[edit]

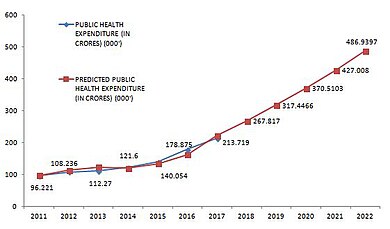

The public health expenditure as a percentage of GDP of the country was 1.3% in 2013-14 was reduced by Modi Government to 1.2% and in the year 2016-17 was increased to 1.5%.[citation needed]

Oil prices

[edit]In October 2014, the Modi government deregulated diesel prices,[26] and later increased taxes on diesel and petrol by Rs 13 and Rs 11 between June 2014 and January 2016 on petrol and diesel respectively.[citation needed]

Later, taxes were decreased by four rupees(Rs 4) between February 2016 and October 2018 for petrol and diesel. Similarly, during January–April 2020, following a sharp decline of 69% in the global crude oil prices, the central government increased the excise duty on petrol and diesel by Rs 10 per litre and Rs 13 per litre, respectively in May 2020.[citation needed]

Because of these subsequent changes in taxes the retail selling prices remained stable in India during the period of fall and increase in prices of global crude oil.[27]

Land reforms

[edit]In order to enable the construction of defence and industrial corridors, the Modi government amend the 2013 Act of land-reform bill that allowed it to acquire private land and without the consent of the owners for "only" these five types of projects:

(i) defence, (ii) rural infrastructure, (iii) affordable housing, (iv) industrial corridors set up by the government/government undertakings, up to one km on either side of the road/railway of the corridor, and (v) infrastructure including PPP projects where the government owns the land.[28]

Under the previous bill (Land Acquisition Act, 2013), the government required 0% consent of landowners for Public Projects of any category, 70% consent of landowners for Public-Private projects and 80% consent for Private Projects.[citation needed]

Public transportation

[edit]The government signed large deals with General Electric and Alstom to supply India with 1,000 new diesel locomotives, as part of an effort to reform the Indian railway, which also included privatisation efforts.[29]

See also

[edit]- Premiership of Narendra Modi

- Timeline of the Narendra Modi premiership

- Foreign policy of the Narendra Modi government

References

[edit]- ^ Ruparelia, Sanjay (12 January 2016). "'Minimum Government, Maximum Governance': The Restructuring of Power in Modi's India". Journal of South Asian Studies. 38 (4): 755–775. doi:10.1080/00856401.2015.1089974. ISSN 0085-6401. S2CID 155182560.

- ^ Shah, Alpa; Lerche, Jens (10 October 2015). "India's Democracy: Illusion of Inclusion". Economic & Political Weekly. 50 (41): 33–36. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ Miglani, Sanjeev; Das, Krishna N. (10 November 2015). "India frees up foreign investment in 15 major sectors". Reuters India. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ "Cabinet approves raising FDI cap in defence to 49 per cent, opens up railways". The Economic Times. 7 August 2014. Archived from the original on 17 October 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ^ Zhong, Raymond (20 November 2014). "Modi Presses Reform for India—But Is it Enough?". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ^ "Reserve Bank of India – Publications". Reserve Bank of India. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Millions strike in India to protest against Modi's labor reforms". CNBC. 3 September 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ "Millions strike in India over government labour reforms". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ Mohan, Archis (12 May 2020). "Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh asks state units to oppose changes in labour laws". Business Standard India. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Budget 2016: Full text of Finance Minister Arun Jaitley's speech". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Overview". World Bank. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Zhong, Raymond; Kala, Anant Vijay (30 January 2015). "India Changes GDP Calculation Method". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ^ "GDP growth slows to 6.1% in Jan-March: Indian economy finally bares its demonetisation scars". Hindustan Times. 1 June 2017. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ^ "WTO deal failure: Valid reasons why PM Narendra Modi's government refused to yield". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Jha, Somesh (17 January 2017). "Domestic air passenger traffic grew 23% in 2016". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Budget 2019: Who gave India a higher GDP – Modi or Manmohan?". Business Today. 1 February 2019. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ V., Harini (14 November 2018). "India's economy is booming. Now comes the hard part". CNBC. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "Unemployment rate at 45-year high, confirms Labour Ministry data". The Hindu. 31 May 2019. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Gettleman, Jeffrey; Kumar, Hari (31 January 2019). "India's Leader Is Accused of Hiding Unemployment Data Before Vote". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ Kumar, Manoj; Ghoshal, Devjyot (31 January 2019). "Indian jobless rate at multi-decade high, report says, in blow to Modi". Reuters. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ Sengupta, Hindol (October 2019). "The economic mind of Narendra Modi". Observer Research Foundation. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ "GDP growth rate for 2018-19 revised downwards to 6.1 pc". The Economic Times. 1 February 2020. Archived from the original on 26 January 2023. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ Mishra, Asit Ranjan (10 January 2019). "What India GDP growth rate forecast for 2018-19 means". Live Mint. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ Choudhury, Gaurav (25 September 2014). "Look East, Link West, says PM Modi at Make in India launch". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015.

- ^ Avishek Majumder (6 December 2018). "Understanding public healthcare expenditures by the Government of India". Project Guru. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Shrivastava, Rahul (18 October 2014). "Narendra Modi Government Deregulates Diesel Prices". NDTV. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ^ "Petrol and Diesel Prices". PRS Legislative Research. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (Second Amendment) Bill, 2015". PRS Legislative Research. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Riley, Charles (10 November 2015). "GE to build 1,000 trains for India in massive deal". CNNMoney. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2021.