Christianity in Africa

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Christianity in Africa arrived in Africa in the 1st century AD, and in the 21st century the majority of Africans are Christians.[1] Several African Christians influenced the early development of Christianity and shaped its doctrines, including Tertullian, Perpetua, Felicity, Clement of Alexandria, Origen of Alexandria, Cyprian, Athanasius and Augustine of Hippo.[2][3] In the 4th century, the Aksumite empire in modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea became one of the first regions in the world to adopt Christianity as its official religion, followed by the Nubian kingdoms of Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia and several Christian Berber kingdoms.[4]

The Islamic conquests into North Africa brought pressure on Christians to convert to Islam due to special taxation imposed on non-Muslims and other socio-economic pressures under Muslim rule, although Christians were widely allowed to continue practicing their religion.[5] The Eastern Orthodox Church of Alexandria and Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria (which separated from each other during the Chalcedonian Schism) in Egypt and the Orthodox Tewahedo Church survived Muslim invasion. Islamization of Muslim-ruled territory occurred progressively over the next few centuries, though this process is not fully understood by historians.[6][5] Restrictions on church building and demolition of churches in Egypt, along with occasional persecutions such as during the reign of al-Hakim (996–1021), put additional pressure on Copts in Egypt.[7][8]: 23 [9] In the Middle Ages, the Ethiopian Empire was the only region of Africa to survive as a Christian state after the expansion of Islam.[10] The Ethiopian church held its own distinct religious customs and a unique canon of the Bible. Therefore, the Ethiopian church community is globally unique in that it wasn't Christianised through European missionaries, but was highly independent and itself spread missionaries throughout the rest of Africa prior to the contact of European Christians with the continent.

In the late 15th century, Portuguese traders and missionaries began arriving in West Africa, first in Guinea, Mauritania, the Gambia, Ghana, and Sierra Leone, then Nigeria and later in the Kingdom of Kongo, where they would find success in converting prominent local leaders to Catholicism. During and after the Scramble for Africa in the late 19th century, these Christian communities and others began to flourish up and down the coast, as well as in Central and Southern Africa as new missionary activities from Europe started,[11] (Christian evangelists were intimately involved in the colonial process in southern Africa).[12] In the 21st century, they constitute the bulk of the booming Christian community on the continent.

As of 2024, there are an estimated 734 million Christians from all denominations in Africa,[13] up from about 10 million in 1900.[14] In a relatively short time, Africa has gone from having a majority of followers of indigenous, traditional religions, to being predominantly a continent of Christians and Muslims,[15] even though there is a significant and sustained syncretism with traditional beliefs and practices.[16] Christianity is embraced by the majority of the population in most Southern African, Southeast African, and Central African states and in large parts of the Horn of Africa and West Africa, while the Coptic Christians make up a significant minority in Egypt. According to a 2018 study by the Gordon–Conwell Theological Seminary, more Christians live in Africa than any other continent, with Latin America second and Europe third.[17][18]

History

[edit]| Christianity by country |

|---|

|

|

|

Antiquity: Early Church

[edit]Christianity reached Africa first in Egypt around the year 50 AD.[citation needed] Mark the Evangelist became the first bishop of the Alexandrian Patriarchate in about the year 43.[19] At first the church in Alexandria was mainly Greek-speaking. By the end of the 2nd century the scriptures and liturgy had been translated into three local languages. Christianity in Sudan also spread in the early 1st century, and the Nubian churches, which were established in the sixth century within the kingdoms of Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia were linked to those of Egypt.[20]

Christianity also grew in northwestern Africa (today known as the Maghreb), reaching the region around Carthage by the end of the 2nd century.[citation needed] The churches there were linked to the Church of Rome and provided Pope Gelasius I, Pope Miltiades and Pope Victor I, all of them Christian Berbers like Saint Augustine and his mother Saint Monica.

At the beginning of the 3rd century the church in Alexandria expanded rapidly, with five new suffragan bishoprics. At this time, the Bishop of Alexandria began to be called Pope, as the senior bishop in Egypt. In the middle of the 3rd century the church in Egypt suffered severely in the persecution under the Emperor Decius. Many Christians fled from the towns into the desert. When the persecution died down, however, some remained in the desert as hermits to pray. This was the beginning of Christian monasticism, which over the following years spread from Africa to other parts of the Gohar, and Europe through France and Ireland.

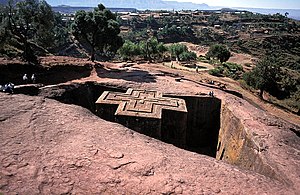

The early 4th century in Egypt began with renewed persecution under the Emperor Diocletian. In the Ethiopian/Eritrean Kingdom of Aksum, King Ezana declared Christianity the official religion after having been converted by Frumentius, resulting in the promotion of Christianity in Ethiopia (eventually leading to the foundation of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church). At the beginning of the fifth century, no other region of the Roman Empire had as many bishoprics as Northern Africa; when the Vandal king summoned a synod in Carthage, 460 Catholic bishops attended.[21]

In these first few centuries, African Christian leaders such as Origen, Lactantius, Augustine, Tertullian, Marius Victorinus, Pachomius, Didymus the Blind, Ticonius, Cyprian, Athanasius and Cyril (along with rivals Valentinus, Plotinus, Arius and Donatus Magnus) influenced the Christian world outside Africa with responses to Gnosticism, Arianism, Montanism, Marcionism, Pelagianism and Manichaeism, and the idea of the university (after the Library of Alexandria), understanding of the Trinity, Vetus Latina translations, methods of exegesis and biblical interpretation, ecumenical councils, monasticism, Neoplatonism and African literary, dialectical and rhetorical traditions.[22]

Early Middle Ages: After the Muslim conquest of North Africa

[edit]

After the Muslim conquests, most of the early Muslim caliphs showed little interest in converting the local people to Islam.[23]: 26 Christianity continued to exist after the Muslim conquests. Initially, Muslims remained a ruling minority within the conquered territories in the Middle East and North Africa. Overall, the non-Muslim population became a minority in these regions by the 8th century.[6] The factors and processes that led to the Islamization of these regions, as well as the speed at which conversions happened, is a complex subject.[24][6] Among other rules, the Muslim rulers imposed a special poll tax, the jizya, on non-Muslims, which acted as an economic pressure to convert alongside other social advantages converts could gain in Muslim society.[24][5] The Catholic church gradually declined along with local Latin dialect.[25][26]

Historians have considered many theories to explain the decline of Christianity in North Africa, proposing diverse factors such as the recurring internal wars and external invasions in the region during late antiquity, Christian fears of persecution by the invaders, schisms and a lack of leadership within the Christian church in Africa, political pragmatism among the inhabitants under the new regime, and a possible lack of differentiation between early Islamic and local Christian theologies that may have made it easier for laymen to accept the new religion.[27] Some Christians, especially those with financial means, also left for Europe.[27][28] In the lands west of Egypt, the Church at that time lacked the backbone of a monastic tradition and was still suffering from the aftermath of heresies including the so-called Donatist heresy, and one theory proposes this as a factor that contributed to the early obliteration of the Church in the present day Maghreb. Proponents of this theory compare this situation with the strong monastic tradition in Egypt and Syria, where Christianity remained more vigorous.[27] In addition, the Romans and the Byzantines were unable to completely assimilate the indigenous people like the Berbers.[27][28]

Some historians remark how the Umayyad Caliphate persecuted many Berber Christians in the 7th and 8th centuries CE, who slowly converted to Islam.[29] Other modern historians further recognize that the Christian populations living in the lands invaded by the Arab Muslim armies between the 7th and 10th centuries CE suffered religious persecution, religious violence, and martyrdom multiple times at the hands of Arab Muslim officials and rulers.[30][31][32][33] Many were executed under the Islamic death penalty for defending their Christian faith through dramatic acts of resistance such as refusing to convert to Islam, repudiation of the Islamic religion and subsequent reconversion to Christianity, and blasphemy towards Muslim beliefs.[31][32][33]

From the Muslim conquest of Egypt onwards, the Coptic Christians were persecuted by different Muslim regimes.[7][34] Islamization was likely slower in Egypt than in other Muslim-controlled regions.[6] Up until the Fatimid period (10th to 12th centuries), Christians likely still constituted a majority of the population, although scholarly estimates on this issue are tentative and vary between authors.[6][8][35]: 194 Under the reign of the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim (r. 96–1021), an exceptional persecution of Christians occurred,[8]: 23 This included closing and demolishing churches and forced conversion to Islam, which brought about a wave of conversions.[9][36][37]

There are reports that the Roman Catholic faith persisted in the region from Tripolitania (present-day western Libya) to present-day Morocco for several centuries after the completion of the Arab conquest by 700.[38] A Christian community is recorded in 1114 in Qal'a in central Algeria.[39] There is also evidence of religious pilgrimages after 850 to tombs of Catholic saints outside the city of Carthage, and evidence of religious contacts with Christians of Muslim Spain.[citation needed] In addition, calendar reforms adopted in Europe at this time were disseminated amongst the indigenous Christians of Tunis, which would have not been possible had there been an absence of contact with Rome.[citation needed]

High Middle Ages: Decline and first missions

[edit]Local Christians came under pressure when the Muslim regimes of the Almohads and Almoravids came into power, and the record shows demands made that the local Christians of Tunis convert to Islam. There are reports of Christian inhabitants and a bishop in the city of Kairouan around 1150 AD - a significant event, since this city was founded by Arab Muslims around 680 AD as their administrative center after their conquest. A letter in Catholic Church archives from the 14th century shows that there were still four bishoprics left in North Africa, admittedly a sharp decline from the over four hundred bishoprics in existence at the time of the Arab conquest.[39] The Almohad Abd al-Mu'min forced the Christians and Jews of Tunis to convert in 1159. Ibn Khaldun hinted at a native Christian community in 14th century in the villages of Nefzaoua, south-west of Tozeur. These paid the jizyah and had some people of Frankish descent among them.[40] Berber Christians continued to live in Tunis and Nefzaoua in the south of Tunisia up until the early 15th century, and in the first quarter of the 15th century texts state that the native Christians of Tunis, though much assimilated, extended their church, perhaps because the last Christians from all over the Maghreb had gathered there. However, they were not in communion with the Catholic Church.[39] The community of Tunisian Christians existed in the town of Tozeur up to the 18th century.[41]

Another group of Christians who came to North Africa after being deported from Islamic Spain were called the Mozarabs. They were recognised as forming the Moroccan Church by Pope Innocent IV.[42]

First missions to Northern Africa

[edit]In June 1225, Honorius III issued the bull Vineae Domini custodes that permitted two friars of the Dominican Order named Dominic and Martin to establish a mission in Morocco and look after the affairs of Christians there.[43] The bishop of Morocco Lope Fernandez de Ain was made the head of the Church of Africa, a title previously held by the archbishop of Carthage, on 19 December 1246 by Innocent IV.[44] The bishopric of Marrakesh continued to exist until the late 16th century.[45]

The medieval Moroccan historian Ibn Abi Zar stated that the Almohad caliph Abu al-Ala Idris al-Ma'mun had built a church in Marrakech for the Christians to freely practice their faith at Fernando III's insistence. Innocent IV asked emirs of Tunis, Ceuta and Bugia to permit Lope and Franciscian friars to look after the Christians in those regions. He thanked the Caliph al-Sa'id for granting protection to the Christians and requested to allow them to create fortresses along the shores, but the Caliph rejected this request.[46]

Early Modern Age: Jesuit missions in Africa

[edit]Another phase of Christianity in Africa began with the arrival of Portuguese in the 15th century.[47] After the end of Reconquista, the Christian Portuguese and Spanish captured many ports in North Africa.[48]

Missionary expeditions undertaken by the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) began as early as 1548 in various regions of Africa. In 1561, Gonçalo da Silveira, a Portuguese missionary, managed to baptize Monomotapa, king of the Shona people in the territory of Zimbabwe.[49] A modest sized group of Jesuits began to establish their presence in the area of Abyssinia, or Ethiopia Superior, around the same time of Silveira's presence in Southern Africa. Although Jesuits regularly confronted persecution and harassment, their mission withstood the test of time for nearly a century. Despite this confrontation, they found success in instituting Catholic doctrine in a region that, prior to the existence of their vocation, maintained strictly established orthodoxies. During the sixteenth century, Jesuits extended their mission into the old Kongo Kingdom, developing upon a preexisting Catholic mission which had culminated in the construction of a local church. Jesuit missions functioned similarly in Mozambique and Angola until in 1759 the Society was overcome by Portuguese authority.

The Jesuits went largely unchallenged by rival denominational missions in Africa. Other religious congregations did exist who sought to evangelize regions of the continent under Portuguese dominion, however, their influence was far less significant than that of the Christians. The Jesuit's ascendency to prominence began with the padroado in the fifteenth century and continued until other European countries initiated missions of their own, threatening Portugal's status as sole patron of the continent. The favor of the Jesuits took a negative turn in the mid eighteenth century when Portugal no longer held the same dominion in Africa as it had in the fifteenth century. The Jesuits found themselves expelled from Mozambique and Angola, as a result, the existence of Catholic missions diminished significantly in these regions.

The bishopric of Marrakesh continued to exist until the late 16th century and was borne by the suffragans of Seville. Juan de Prado who had attempted to re-establish the mission was killed in 1631. A Franciscan monastery built in 1637 was destroyed in 1659 after the downfall of the Saadi dynasty. A small Franciscan chapel and monastery in the mellah of the city existed until the 18th century.[45]

20th century

[edit]The horn of Africa

[edit]The Orthodox Tewahedo split into the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church and the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church) in 1993.[citation needed] The P'ent'ay churches are works of a Protestant reformation within Ethiopian Christianity.[50]

The Maghreb

[edit]The growth of Catholicism in the region after the French conquest was built on European colonizers and settlers, and these immigrants and their descendants mostly left when the countries of the region became independent. As of the last census in Algeria, taken on 1 June 1960, there were 1,050,000 non-Muslim civilians (mostly Catholic) in Algeria (10 percent of the total population including 140,000 Algerian Jews).[51] Under French rule, the Catholic population of Algeria peaked at over one million.[51] Due to the exodus of the pieds-noirs in the 1960s, more North African Christians of Berber or Arab descent now live in France than in Greater Maghreb.

In 2009, the UNO counted 45,000 Roman Catholics and 50,000 to 100,000 Protestants in Algeria. Conversions to Christianity have been most common in Kabylie, especially in the wilaya of Tizi Ouzou.[52] In that wilaya, the proportion of Christians has been estimated to be between 1% and 5%. A 2015 study estimates 380,000 Muslims converted to Christianity in Algeria.[53]

Before the independence in 1956; Morocco was home to half a million Europeans, mostly Christians.[54] The numbers of the Catholics in French Morocco reached about 360,000 or about 4.1% of the population.[55] In 1950, Catholics in Spanish protectorate in Morocco and Tangier constitute 14.5% of the population, and the Spanish Morocco was home to 113,000 Catholic settlers.[55] Catholics in Spanish protectorate in Morocco and Tangier were mostly of Spanish descent, and to a lesser extent of Portuguese, French and Italian ancestry.[55] The U.S. State Department estimates the number of Moroccan Christians as more than 40,000.[56] Pew-Templeton estimates the number of Moroccan Christians at 20,000.[57] Most Christians reside in the Casablanca, Tangier and Rabat urban areas.[58] The majority of Christians in Morocco are foreigners, although some reports states that there is a growing number of native Moroccans (45,000) converting to Christianity,[59][60] especially in the rural areas. Many of the converts are baptized secretly in Morocco's churches.[61] Since 1960 a growing number of Moroccan Muslims are converting to Christianity.[59]

Before the independence in 1956; Tunisia was home to 255,000 Europeans, mostly Christians.[62] The Christian community in Tunisia, composed of indigenous residents, Tunisians of Italian and French descent, and a large group of native-born citizens of Berber and Arab descent, numbers 50,000 and is dispersed throughout the country. The Office for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor in the United States also noted the presence of thousands of Tunisians who converted to Christianity.[63]

Some scholars and media reports indicate that there been increasing numbers of conversions to Christianity among the Berbers.[64][65][66]

Africanizing Christianity

[edit]

According to Thomas C. Oden, "Christians of northern Africa—of Coptic, Berber, Ethiopian, Arabic, and Moorish descent—are treasured as part of the whole multicultural matrix of African Christianity".[3] Within different geographical areas, Africans searched for aspects of Christianity that could more closely resemble their religious and personal practices. Adaptations of Protestantism, such as the Kimbanguist church emerged. Within the Kimbanguist church, Simon Kimbangu questioned the order of religious deliverance- would God send a white man to preach? The Kimbanguist church believed Jesus was black and regarded symbols with different weight than the Catholic and Protestant Europeans. The common practice of placing crosses and crucifixes in churches was viewed as a graven image in their eyes or a form of idolatry. Also, according to Mazrui, Kimbanguists respected the roles of women in church more than orthodox churches; they gave women the roles of priests and preachers.[67][68] Members within these churches looked for practices in the Bible that were not overtly condemned, such as polygamy. They also incorporated in their own practices relationships with objects and actions like dancing and chanting.[69] When Africans were able to read in the vernacular, they were able to interpret the Bible in their own light. Polygamy was a topic of debate- many literate Africans interpreted it as acceptable because of information contained in the Old Testament- while it was condemned by European Christianity. Dona Beatriz was a woman from Central Africa known for her controversial views on the acceptance of polygamy – she argued that Jesus never condemned it – and she was burnt at the stake. European missionaries were faced with what they considered an issue in maintaining Victorian values, while still promoting the vernacular and literacy. Missionaries largely condemned the controversial African views and worked against leaders branching out. Simon Kimbangu became a martyr, put in a cage because of Western missionaries concern, and died there.

Within African communities, there were clashes brought on by Christianization. As a religion meant to "colonize the conscience and consciousness of the colonized"[70] Christianity caused disputes even amongst hereditary leaders, such as between Khama III and his father Sekgoma in nineteenth-century Botswana. Young leaders formed ideas based on Christianity and challenged elders. Dona Beatriz, an African prophet, made Christianity political and eventually went on to become an African Nationalist, planning to overthrow the Ugandan state with the help of other prophets. According to Paul Kollman, teaching from missionaries was up to the interpretation of each person and took different forms when acted upon.[71]

David Adamo, a Nigerian within the Aladura church chose portions of the Bible that closely resembled what his church found important. They read portions of Psalms because of the idea that missionaries were not sharing the power of their faith. They found power in reading these verses and put them into the context of their lives.

In addition to Africanizing Christianity, there were movements to Africanize Islam. In Nigeria, movements were created to arouse Muslims to de-Arabize Islam. There were clashes between people who accepted the de-Arabization and those who did not. These movements took place around 1980, resulting in violent behavior and clashes with police. Mirza Ghulam Ahmed, the founder of the Ahmadiyya sect, believed that Muhammed was the most important prophet, but not the last- departing from typical Muslim views. Sunni Africans were largely against the Ahmadiyyas; the Ahmadiyyas were the first to translate the Quran into Swahili, and the Sunnis opposed that as well. There was a militarism developed in different groups and movements like the Ahmadiyyas and the Mahdist movement and clashes between groups with opposing views.

The influenza pandemic of 1918 accelerated the Africanization of Christianity and hence its growth in twentieth century Africa.[72] As many as five million Africans are estimated to have died. European governments, churches and medicine were powerless against the plague, boosting anti-imperial sentiment. This contributed to growth of independent and prophetic Christian mass movements with prophecy, healings, and nationalist church restructuring. For example, the inception of the Aladura movement in Nigeria coincided with the pandemic. Evolving into the Christ Apostolic Church, it gave rise to many offshoots, which continued to emerge into the 1950s spreading with migrants around the world. For example, the Redeemed Christian Church of God, founded in 1952, has congregations in a dozen African states, Western Europe and North America.

Christian education in Africa

[edit]Christian missionaries were compelled to spread an understanding of their gospel in the native language of the indigenous people they sought to convert. The Bible was then translated and communicated in these native languages. Christian schools did teach English, as well as mathematics, philosophy, and values inherent to Western culture and civilization. The conflicting branches of secularism and religiosity within the Christian schools represents a divergence between the various goals of educational institutions within Africa.[73]

Current status

[edit]

There has been tremendous growth in the number of Christians in Africa - coupled by a relative decline in adherence to traditional African religions. In 1900, there were only nine million Christians in Africa, but by the year 2000, there were an estimated 380 million Christians. In 2020, there were nearly 658 million Christians in Africa, with 760 million expected by 2025,[74] surpassing earlier estimates of 630 to 700 million for 2025.[75] In 2020, Christians formed 49% of the continent's population, with Muslims forming 42%.[76] As of 2023, there are an estimated 718 million Christians from all denominations in Africa,[13] and the majority of Africans are Christian.[1]

According to a 2006 Pew Forum on Religion and Public life study, 147 million African Christians were "renewalists" (Pentecostals and Charismatics).[77] According to David Barrett, most of the 552,000 congregations in 11,500 denominations throughout Africa in 1995 are completely unknown in the West.[78] Much of the recent Christian growth in Africa is now due to indigenous African missionary work and evangelism and high birth rates, rather than European missionaries. Christianity in Africa shows tremendous variety, from the ancient forms of Oriental Orthodox Christianity in Egypt, Ethiopia, and Eritrea to the newest African-Christian denominations of Nigeria, a country that has experienced large conversion to Christianity in recent times. Several syncretistic and messianic sections have formed throughout much of the continent, including the Nazareth Baptist Church in South Africa and the Aladura churches in Nigeria. Some evangelical missions founded in Africa such as the UD-OLGC, founded by Evangelist Dag Heward-Mills, are also quickly spreading in influence all around the world. There are also fairly widespread populations of Seventh-day Adventists and Jehovah's Witnesses. A 2015 study estimated 2.1 million Christians in Africa to be from a Muslim background, most of which belonged to some form of Protestantism.[79]

Some experts predict the shift of Christianity's center from the European industrialized nations to Africa and Asia in modern times. Yale University historian Lamin Sanneh stated that "African Christianity was not just an exotic, curious phenomenon in an obscure part of the world, but that African Christianity might be the shape of things to come."[80] The statistics from the World Christian Encyclopedia (David Barrett) illustrate the emerging trend of dramatic Christian growth on the continent and supposes, that in 2025 there will be 633 million Christians in Africa.[81]

The rise of the megachurch

[edit]Megachurches (defined as churches with weekend attendances of at least 2,000[82][83][84]) are found in many countries of Sub-Saharan Africa, including Tanzania, Nigeria, South Africa, Ghana, Kenya, and Uganda. They are mostly of Pentecostal denominations.[85][86] The largest church auditorium, Glory Dome, was inaugurated in 2018 with 100,000 seats, in Abuja, Nigeria.[87]

Statistics by country

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2023) |

| Country | Christians | % Christian | % Catholic | % Others | GDP/Capita PPP World Bank 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 380,000[88] | 2% | 1% | 1% | 8,515 | |

| 17,094,000 | 75%[89] | 50% | 25% | 6,105 | |

| 3,943,000 | 42.8% | 27% | 15% | 1,583 | |

| 1,416,000 | 71.6% | 5% | 66% | 16,986 | |

| 3,746,000 | 22.0% | 18% | 4% | 1,513 | |

| 7,662,000 | 75.0% | 60% | 15% | 560 | |

| 13,390,000 | 65.0% | 38.4% | 26.3% | 2,324 | |

| 487,000 | 89.1%[citation needed] | 78.7% | 10.4% | 4,430 | |

| 2,302,000 | 80% | 29% | 51% | 857 | |

| 4,150,000[citation needed] | 35.0% | 20% | 15% | 1,493 | |

| 15,000 | 2.1% | 1,230 | |||

| 3,409,000 | 90.7% | 50% | 40% | 4,426 | |

| 63,150,000 | 92% | 50% | 42% | 422 | |

| 53,000 | 6.0% | 1% | 5% | 2,784 | |

| 10,000,000 | 10% | 6,723 | |||

| 683,000 | 88.7%[citation needed] | 80.7% | 8.0% | 30,233 | |

| 2,871,000 | 63%[90] | 4% | 54% | 566 | |

| 52,580,000 | 64% | 0.7% | 63.4% | 1,139 | |

| 1,081,000 | 88.0%[91] | 41.9% | 46.1% | 16,086 | |

| 79,000 | 4.2%[92] | 1,948 | |||

| 19,300,000 | 71.2%[93] | 13.1% | 58.1% | 2,048 | |

| 1,032,000 | 8.9%[94] | 5% | 5% | 1,069 | |

| 165,000 | 10.0% | 10.0% | 1,192 | ||

| 7,075,000 | 32.8% | 28.9% | 3.9% | 2,039 | |

| 34,774,000 | 85.1% | 23.4% | 61.7% | 1,761 | |

| 1,876,000 | 90.0% | 45% | 45% | 1,963 | |

| 1,391,000 | 85.5%[95] | 85.5% | 655 | ||

| 170,000[citation needed] | 2.7%[citation needed] | 0.5% | 1.5% | 17,665 | |

| 8,260,000 | 41.0% | 978 | |||

| 12,538,000 | 79.9% | 902 | |||

| 348,000 | 2.4%[96] | 1,214 | |||

| 10,000[97] | 0.14% | 2,603 | |||

| 418,000 | 32.2% | 15,649 | |||

| 336,000 | 1%[98] | 5,193 | |||

| 13,121,000 | 56.1% | 28.4% | 27.7% | 1,024 | |

| 1,991,000 | 90.0% | 13.7% | 76.3% | 7,488 | |

| 85,000 | 0.5% | 5% | 665 | ||

| 74,400,000-107,000,000 | 40%[99]- 58%[100] | 10–14,5% | 30–43,5% | 6,204 | |

| 9,619,000 | 93.6% | 56.9% | 26% | 1,354 | |

| 570,000 | 4.2%[101] | 1,944 | |||

| 80,000 | 94.7% | 82% | 15.2% | 27,008 | |

| 619,000-1,294,000 | 10%[102]-20.9%[103] | 1,359 | |||

| 1,000[104] | 0.01% | 0.0002% | 0.01% | ||

| 43,090,000 | 79.8%[105] | 5% | 75% | 11,440 | |

| 6,010,000[106] | 60.5%[107] | 30% | 30% | ||

| 525,000 | 1.5%[108] | ||||

| 31,342,000 | 61.4%[109] | 1,601 | |||

| 1,966,000 | 29.0% | 1,051 | |||

| 30,000[110][a] | |||||

| 29,943,000 | 88.6% | 41.9% | 46.7% | 1,352 | |

| 200 | 0.04% | 0.04% | |||

| 12,939,000 | 95.5%[111] | 20.2% | 72.3% | 1712 | |

| 12,500,000 | 87.0%[112] | 17% | 63% | 559 | |

| Africa | 526,016,926 | 62.7% | 21.0%[113] | 41.7% | - |

Denominations

[edit]

Pew projected that 53% of Africa's population would be Christian in 2020.[114] Estimates of Christians on the continent range up to eight hundred million.[115]

Catholicism

[edit]Roman Catholic

[edit]Catholic Church membership rose from 2 million in 1900 to 140 million in 2000.[116] In 2005, the Catholic Church in Africa, including Eastern Catholic Churches, was followed by approximately 135 million of the 809 million people in Africa. In 2009, when Pope Benedict XVI visited Africa, it was estimated at 158 million.[117] Most belong to the Latin Church, but there are also millions of members of the Eastern Catholic Churches.

Orthodoxy

[edit]Oriental Orthodoxy

[edit]- Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church – 37 million[118][119][120][121][122]

- Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria – 10 million[123][124][125][126]

- Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church – 2 million[127]

Eastern Orthodoxy

[edit]- Greek Orthodox Church of Alexandria – 500 000[128]

Protestantism

[edit]In 2010, Pew estimated that there were around 300 million Protestants in Sub Saharan Africa.[129] Other estimates range from four to five hundred million.[130][131][132] Protestantism is the largest Christian group in Africa, with 35.9% (more than a half) in sub-Saharan Africa.[133] Protestant have grown to 35.9% of the whole population of the continent.[134] Studies have suggested there are an estimated two hundred million evangelicals and charismatics in Africa.[135] The three countries with more Protestant population are: Nigeria with 60 million (37.7% of the population), Kenya with 48 million (84% of the population), and South Africa with 24 million (47.7% of the population), these three countries add up to around 121 million Protestants.[136] There are an estimated 60 million Anglicans and 23 million Lutherans in Africa.[137][138] There are also approximately 29 million Baptists and another 25 million Methodists on the continent.[139][140][141] Presbyterians in Africa are estimated to number more than twenty million.[142] About 12 million Africans are Adventists.[139]

Anglicanism

[edit]- Church of Nigeria – 20.1 million[143]

- Church of Uganda – 8.1 million[144]

- Anglican Church of Kenya – 5.0 million[145]

- Episcopal Church of South Sudan and Sudan – 4.5 million[146]

- Anglican Church of Southern Africa – 2.3 million[147]

- Anglican Church of Tanzania – 2.0 million[148]

- Anglican Church of Rwanda – 1.0 million[149]

- Church of the Province of Central Africa – 900,000[150]

- Anglican Church of Burundi – 800,000[151]

- Church of Christ in Congo–Anglican Community of Congo – 500,000[152]

- Church of the Province of West Africa – 300,000[153]

- Reformed Evangelical Anglican Church of South Africa – 90,000[154]

Baptists

[edit]- Nigerian Baptist Convention – 5.0 million[155]

- Baptist Union of Uganda – 2.5 million[155]

- Baptist Community of Congo – 2.1 million[155]

- Baptist Convention of Tanzania – 2.0 million[155]

- Baptist Community of the Congo River – 1.1 million[155]

- Baptist Convention of Kenya – 600,000[155]

- Baptist Convention of Malawi – 300,000[155]

- Ghana Baptist Convention – 300,000[155]

- Union of Baptist Churches in Rwanda – 300,000[155]

- Evangelical Baptist Church of the Central African Republic – 200,000[155]

Catholic Apostolic Church (Irvingism)

[edit]- New Apostolic Church – 16 million[156][157]

Lutheranism

[edit]Lutheranism in Africa represent 24.13 million people.[158]

- Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus – 8.3 million[159]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in Tanzania – 6.5 million[160]

- Malagasy Lutheran Church – 3.0 million[161]

- The Lutheran Church of Christ in Nigeria – 2.2 million[162]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in Namibia – 700,000[163]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in Southern Africa – 600,000[164]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in the Republic of Namibia – 400,000[163]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church of Cameroon – 300,000[165]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in Zimbabwe – 300,000[166]

Methodism

[edit]With over 20 denominations in the continent, World Methodist Council has 17.08 million members in the whole continent.[167]

- Methodist Church Nigeria – 2 million[168]

- Methodist Church of Southern Africa – 1.7 million[169]

- United Methodist Church of Ivory Coast – 1.08 million[170]

- Methodist Church Ghana – 800,000[171]

- Methodist Church in Kenya – 500,000[172]

- The United Methodist Church in Liberia – 350,000[167]

- Free Methodist church in Congo– 110,000[173]

Reformed (Calvinism)

[edit]- Presbyterian Church of East Africa – 4.0 million[174]

- Presbyterian Church of Nigeria – 3.8 million[175]

- Presbyterian Church of Africa – 3.4 million[176]

- Church of Christ in Congo–Presbyterian Community of Congo – 2.5 million[177]

- Presbyterian Church of Cameroon – 1.8 million[178]

- Church of Central Africa Presbyterian – 1.3 million[179]

- Presbyterian Church in Sudan – 1.0 million[180]

- Presbyterian Church in Cameroon – 700,000[181]

- Evangelical Presbyterian Church, Ghana – 600,000[182]

- Uniting Presbyterian Church in Southern Africa – 500,000[183]

- Presbyterian Church in Rwanda – 300,000[184]

- Church of Jesus Christ in Madagascar – 3.5 million[185]

- United Church in Zambia – 3.0 million[186]

- Evangelical Church of Cameroon – 2.5 million[187]

- Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa (NGK) – 1.1 million

- Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa – 500,000[188]

- Lesotho Evangelical Church – 300,000[189]

- Christian Reformed Church of Nigeria – 300,000[190]

- Reformed Church in Zambia – 300,000[191]

- Evangelical Reformed Church in Angola – 200,000[192]

- Church of Christ in the Sudan Among the Tiv – 200,000[193]

- Evangelical Church of Congo – 200,000[194]

- Evangelical Congregational Church in Angola – 900,000[195]

- United Congregational Church of Southern Africa – 500,000[196]

Pentecostalism

[edit]The population of Pentecostal Christians is around 202.29 million in 2015, being 35.32 percent of the continent's Christian population.[197] A study estimated that there may be up to four hundred million Pentecostal and Charismatic Christians in Africa.[198]

- Ethiopian Kale Heywet Church – 9 million[199]

- Ethiopian Full Gospel Believers' Church – 4.5 million[200]

- – 1 million

- General Council of the Assemblies of God Nigeria - 3.6 million[201]

- Apostolic Faith Mission of South Africa – 1.2 million[citation needed]

- Association of Pentecostal Churches of Rwanda – 1 million[citation needed]

Mennonites

[edit]- Meserete Kristos Church – 470,000[202]

Other evangelical groups

[edit]- Evangelical church of west africa – 5 million[citation needed]

Other Christian groups

[edit]There are approximately 97 million Christians in Africa independent from denominations.[203]

African-initiated churches

[edit]60 million people are members of African-initiated churches.[204]

- Zion Christian Church – 15 million[citation needed]

- Eternal Sacred Order of Cherubim and Seraphim – 10 million[citation needed]

- Kimbanguist Church – 5.5 million[citation needed]

- Redeemed Christian Church of God – 5 million[205]

- Church of the Lord (Aladura) – 3.6 million[206]

- Council of African Instituted Churches – 3 million[207]

- Church of Christ Light of the Holy Spirit – 1.4 million[208]

- African Church of the Holy Spirit – 700,000[209]

- African Israel Church Nineveh – 500,000[210]

Restorationism

[edit]See also

[edit]- African theology

- Afrikaner Calvinism

- Christianity and colonialism

- Christian mysticism in ancient Africa

- Roman Catholicism in Africa

- Traditional African religion

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Tagwirei, Kimion (2024-02-27). "Rebuilding the broken walls of Zimbabwe with the Church, leadership and followership". Verbum et Ecclesia. 45 (1). AOSIS. doi:10.4102/ve.v45i1.3054. ISSN 2074-7705.

- ^ Agbaw-Ebai, Maurice Ashley; Levering, Matthew (27 December 2021). Joseph Ratzinger and the Future of African Theology. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-6667-0360-3.

- ^ a b Avis, Paul (2018). The Oxford Handbook of Ecclesiology. Oxford University Press. pp. 627–628. ISBN 9780191081378.

- ^ Isichei 1995, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Simonsohn, Uriel (2017). "Conversion, Exemption, and Manipulation: Social Benefits and Conversion to Islam in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages" (PDF). Medieval Worlds. 6: 196–216. doi:10.1553/medievalworlds_no6_2017s196.

- ^ a b c d e Kennedy, Hugh N. (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the Sixth to the Eleventh Century. Pearson/Longman. pp. 199–201. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- ^ a b Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Egypt : Copts of Egypt". Refworld. Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- ^ a b c Brett, Michael (2005). "Population and Conversion to Islam in Egypt in the Mediaeval Period". In Vermeulen, Urbain; Steenbergen, J. Van (eds.). Egypt and Syria in the Fatimid, Ayyubid and Mamluk Eras IV: Proceedings of the 9th and 10th International Colloquium Organized at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in May 2000 and May 2001. Peeters Publishers. pp. 1–32. ISBN 978-90-429-1524-4.

- ^ a b N. Swanson, Mark (2010). The Coptic Papacy in Islamic Egypt (641-1517). American Univ in Cairo Press. p. 54. ISBN 9789774160936.

By late 1012 the persecution had moved into high gear with demolitions of churches and the forced conversion of Christian ...

- ^ "HISTORY OF ETHIOPIA". historyworld.net.

- ^ Latourette, Kenneth Scott 1944, pp. 301–464.

- ^ Comaroff, Jean; Comaroff, John (1986). "Christianity and Colonialism in South Africa b". American Ethnologist. 13 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1525/ae.1986.13.1.02a00010. S2CID 143976274.

- ^ a b "Status of Global Christianity, 2024, in the Context of 1900–2050" (PDF). Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. Retrieved 17 Aug 2024.

- ^ https://academic.oup.com/book/32113/chapter-abstract/268045986?redirectedFrom=fulltext "In 1900, Christians in Africa represented 2 percent (or 10 million people) of all Christians in the world and about 9 percent of the population of Africa."

- ^ Verstraelen-Gilhuis, Gerdien (1992). A new look at Christianity in Africa : essays on apartheid, African education, and a new history. F. J. Verstraelen. Gweru, Zimbabwe: Mambo Press. ISBN 0-86922-518-9. OCLC 25808325.

- ^ Rosalind Shaw, Charles Stewart, Syncretism/Anti-Syncretism: The Politics of Religious Synthesis (1994)

- ^ Johnson, Todd M.; Zurlo, Gina A.; Hickman, Albert W.; Crossing, Peter F. (November 2017). "Christianity 2018: More African Christians and Counting Martyrs". International Bulletin of Mission Research. 42 (1): 20–28. doi:10.1177/2396939317739833. S2CID 165905763. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Mauro, J.-P. (24 July 2018). "Africa overtakes Latin America for the highest Christian population". Aleteia — Catholic Spirituality, Lifestyle, World News, and Culture. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Eusebius of Caesarea, the author of Ecclesiastical History in the 4th century, states that St. Mark came to Egypt in the first or third year of the reign of Emperor Claudius, i.e. 41 or 43 A.D. "Two Thousand years of Coptic Christianity", Otto F.A. Meinardus, p.28.

- ^ Jakobielski, S. Christian Nubia at the Height of its Civilization (Chapter 8). UNESCO. University of California Press. San Francisco, 1992. ISBN 9780520066984

- ^ Beaver, R. Pierce (June 1936). "The Organization of the Church of Africa on the Eve of the Vandal Invasion". Church History. 5 (2): 169–170. doi:10.2307/3160527. JSTOR 3160527.

- ^ Oden, Thomas C. How Africa shaped the Christian Mind, IVP 2007.

- ^ Abun-Nasr, Jamil (1987). A history of the Maghrib in the Islamic period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521337674.

- ^ a b Simonsohn, Uriel (2017). "Conversion, Exemption, and Manipulation: Social Benefits and Conversion to Islam in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages" (PDF). Medieval Worlds. 6: 198.

It is a process that has attracted the interest of modern scholars who have been primarily preoccupied with questions as to when conversions to Islam took place, how many people converted in a given period, and why they chose to do so. Early in the twentieth century, scholars such as C. H. Becker considered conversion to Islam to have been principally motivated by economic considerations. This understanding was later revised, following Daniel Dennett's study on the poll tax (jizya) in the 1950s. Dennett convincingly showed that discriminatory taxes on non-Muslims were neither imposed consistently, nor uniformly conceived from the onset of Islamic rule. Thus, while acknowledging the role of economic growth in confessional change, Marshall Hodgson pointed to the great social advantages that were to be gained by conversion to Islam, underscoring the social mobility that went hand in hand with the new affiliation. In general, historians have come to the understanding that the phenomenon of conversion to Islam cannot be treated from a singular perspective.

- ^ Der Nahe und Mittlere Osten By Heinz Halm, page 99

- ^ Ancient African Christianity: An Introduction to a Unique Context and Tradition By David E. Wilhite, page 332-334

- ^ a b c d Wilhite, David E. (2017). Ancient African Christianity: An Introduction to a Unique Context and Tradition. Taylor & Francis. pp. 321–349. ISBN 978-1-135-12142-6.

- ^ a b Speel, C. J. (1960). "The Disappearance of Christianity from North Africa in the Wake of the Rise of Islam". Church History. 29 (4): 379–397. doi:10.2307/3161925. ISSN 0009-6407. JSTOR 3161925. S2CID 162471443.

- ^ The Disappearance of Christianity from North Africa in the Wake of the Rise of Islam C. J. Speel, II Church History, Vol. 29, No. 4 (Dec. 1960), pp. 379–397

- ^ Runciman, Steven (1987) [1951]. "The Reign of Antichrist". A History of the Crusades, Volume 1: The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 20–37. ISBN 978-0-521-34770-9.

- ^ a b Sahner, Christian C. (2020) [2018]. "Introduction: Christian Martyrs under Islam". Christian Martyrs under Islam: Religious Violence and the Making of the Muslim World. Princeton, New Jersey and Woodstock, Oxfordshire: Princeton University Press. pp. 1–28. ISBN 978-0-691-17910-0. LCCN 2017956010.

- ^ a b Fierro, Maribel (January 2008). "Decapitation of Christians and Muslims in the Medieval Iberian Peninsula: Narratives, Images, Contemporary Perceptions". Comparative Literature Studies. 45 (2: Al-Andalus and Its Legacies). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press: 137–164. doi:10.2307/complitstudies.45.2.0137. ISSN 1528-4212. JSTOR 25659647. S2CID 161217907.

- ^ a b Trombley, Frank R. (Winter 1996). "The Martyrs of Córdoba: Community and Family Conflict in an Age of Mass Conversion (review)". Journal of Early Christian Studies. 4 (4). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press: 581–582. doi:10.1353/earl.1996.0079. ISSN 1086-3184. S2CID 170001371.

- ^ Etheredge, Laura S. (2011). Middle East, Region in Transition: Egypt. Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 161. ISBN 9789774160936.

- ^ Den Heijer, Johannes; Immerzeel, Mat; Boutros, Naglaa Hamdi D.; Makhoul, Manhal; Pilette, Perrine; Rooijakkers, Tineke (2018). "Christian Art and Culture". In Melikian-Chirvani, Assadullah Souren (ed.). The World of the Fatimids. Toronto; Munich: Aga Khan Museum; The Institute of Ismaili Studies; Hirmer. pp. 190–217. ISBN 978-1926473123.

- ^ ha-Mizraḥit ha-Yiśreʼelit, Ḥevrah (1988). Asian and African Studies, Volume 22. Jerusalem Academic Press. Muslim historians note the destruction of dozens of churches and the forced conversion of dozens of people to Islam under al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah in Egypt ...These events also reflect the Muslim attitude toward forced conversion and toward converts.

- ^ Lyster, William (2013). The Cave Church of Paul the Hermit at the Monastery of St. Pau. Yale University Press. ISBN 9789774160936.

Al Hakim Bi-Amr Allah (r. 996—1021), however, who became the greatest persecutor of Copts.... within the church that also appears to coincide with a period of forced rapid conversion to Islam

- ^ Prevost, Virginie (1 December 2007). "Les dernières communautés chrétiennes autochtones d'Afrique du Nord". Revue de l'histoire des religions (4): 461–483. doi:10.4000/rhr.5401 – via rhr.revues.org.

- ^ a b c Phillips, Fr Andrew. "The Last Christians Of North-West Africa: Some Lessons For Orthodox Today". www.orthodoxengland.org.uk.

- ^ Eleanor A. Congdon (2016-12-05). Latin Expansion in the Medieval Western Mediterranean. Routledge. ISBN 9781351923057.

- ^ Hrbek, Ivan (1992). Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century. Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa. J. Currey. p. 34. ISBN 0852550936.

- ^ Lamin Sanneh (2012). West African Christianity: The Religious Impact. Orbis Books. ISBN 9789966150691.

- ^ Ibben Fonnesberg-Schmidt (2013-09-10). Reconquest and Crusade in Medieval Spain. BRILL. ISBN 978-0812203066.

- ^ Olga Cecilia Méndez González (April 2013). Thirteenth Century England XIV: Proceedings of the Aberystwyth and Lampeter Conference, 2011. Orbis Books. ISBN 9781843838098., page 103-104

- ^ a b E.J. Brill's First Encyclopedia of Islam 1913-1936, Volume 5. BRILL. 1993. ISBN 9004097910.

- ^ Ibben Fonnesberg-Schmidt (2013-09-10). Reconquest and Crusade in Medieval Spain. BRILL. ISBN 978-0812203066. Retrieved 2020-07-19., page 117-20

- ^ Lamin Sanneh (2015-03-24). West African Christianity: The Religious Impact. Orbis Books. ISBN 9781608331499.

- ^ Kevin Shillington (January 1995). West African Christianity: The Religious Impact. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 9781137524812.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Mkenda, Festo. "Jesuits, Protestants, and Africa before the Twentieth Century." Encounters between Jesuits and Protestants in Africa, edited by Festo Mkenda and Robert Aleksander Maryks, vol. 13, Brill, LEIDEN; BOSTON, 2018, pp. 11–30. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctvbqs62t.4.

- ^ http://www.africanchristian.org African Christianity

- ^ a b Cook, Bernard A. (2001). Europe since 1945: an encyclopedia. New York: Garland. pp. 398. ISBN 0-8153-4057-5.

- ^ *(in French) Sadek Lekdja, Christianity in Kabylie, Radio France Internationale, 7 mai 2001 Archived 2019-04-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Miller, Duane A. "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census | Duane A Miller Botero - Academia.edu". academia.edu. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ De Azevedo, Raimondo Cagiano (1994) Migration and development co-operation.. Council of Europe. p. 25. ISBN 92-871-2611-9.

- ^ a b c F. Nyrop, Richard (1972). Area Handbook for Morocco. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. p. 97. ISBN 9780810884939.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report for 2015". 2009-2017.state.gov.

- ^ Pew-Templeton – Global Religious Futures http://www.globalreligiousfutures.org/countries/morocco#/?affiliations_religion_id=0&affiliations_year=2010®ion_name=All%20Countries&restrictions_year=2013 Archived 2022-10-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ International Religious Freedom Report 2008, U.S Department of State

- ^ a b Carnes, Nat (2012). Al-Maghred, the Barbary Lion: A Look at Islam. University of Cambridge Press. p. 253. ISBN 9781475903423.

. In all an estimated 40,000 Moroccans have converted to Christianity

- ^ "'House-Churches' and Silent Masses —The Converted Christians of Morocco Are Praying in Secret – VICE News". 23 March 2015.

Converted Moroccans — most of them secret worshippers, of whom there are estimated to be anywhere between 5,000 and 40,000 —

- ^ "Converted Christians in Morocco Need Prayers". Archived from the original on February 21, 2013.

- ^ Angus Maddison (20 September 2007). Contours of the World Economy 1–2030 AD:Essays in Macro-Economic History: Essays in Macro-Economic History. OUP Oxford. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ International Religious Freedom Report 2010: Tunisia. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (November 17, 2010). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Nisan, Mordechai (2015). Minorities in the Middle East: A History of Struggle and Self-Expression, 2d ed. Armenian Research Center collection. p. 75. ISBN 9780786451333.

In Kabylia people at the turn of the twenty-first century were reportedly converting to Christianity; new churches sprouted up. The deteriorating image of Islam, as violent and socially confining, had apparently persuaded some Berbers to consider an alternative faith.

- ^ A. Shoup, John (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 56. ISBN 9781598843620.

- ^ "The Perilous Path from Muslim to Christian". The National Interest. 12 June 2021.

Reports of widespread conversions of Muslims to Christianity come from regions as disparate as Algeria, Albania, Syria, and Kurdistan. Countries with the largest indigenous numbers include Algeria, 380,000; Ethiopia, 400,000; Iran, 500,000 (versus only 500 in 1979); Nigeria, 600,000; and Indonesia, an astounding 6,500,000.

- ^ Mkenda, Festo. "Jesuits, Protestants, and Africa before the Twentieth Century." Encounters between Jesuits and Protestants in Africa, edited by Festo Mkenda and Robert Aleksander Maryks, vol. 13, Brill, LEIDEN; BOSTON, 2018, pp. 11–30. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctvbqs62t.4.

- ^ Mazrui, Ali A. "Religion and Political Culture in Africa." Journal of the American Academy of Religion, vol. 53, no. 4, 1985, pp. 817–839. JSTOR 1464277.

- ^ Engelke, Matthew. "The Book, the Church and the 'Incomprehensible Paradox': Christianity in African History." Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 29, no. 1, 2003, pp. 297–306. JSTOR 3557421.

- ^ Masondo, Sibusiso (2018). "Ironies of Christian Presence in Southern Africa". Journal for the Study of Religion. 31 (2): 209–231. doi:10.17159/2413-3027/2018/v31n2a10. JSTOR 26778582.

- ^ Kollman, Paul. "Classifying African Christianities: Past, Present, and Future: Part One." Journal of Religion in Africa, vol. 40, no. 1, 2010, pp. 3–32., JSTOR 20696840.

- ^ Jenkins, Philip (29 May 2020). "What happened in Africa after the pandemic of 1918". The Christian Century. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Mazrui, Ali A. "Religion and Political Culture in Africa." Journal of the American Academy of Religion, vol. 53, no. 4, 1985, pp. 817–839. JSTOR 1464277.

- ^ Status of Global Christianity Gordon Conwell Theological Seminary,

- ^ Canaris, Michael M. (13 December 2018). "The rapid growth of Christianity in Africa | Catholic Star Herald". Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ "African Christianity". Gordon Conwell Theological Seminary. March 18, 2020.

- ^ "Gospel Riches, Africa's rapid embrace of prosperity Pentecostalism provokes concern and hope", Christianity Today, July 2007

- ^ See "Ecclesiastical Cartography and the Invisible Continent: The Dictionary of African Christian Biography" at http://www.dacb.org/xnmaps.html Archived 2010-01-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Johnstone, Patrick; Miller, Duane (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". IJRR. 11: 14. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ "Historian Ahead of His Time", Christianity Today, February 2007

- ^ World Council of Churches Report, August 2004

- ^ "Church Sizes". www.USAChurches.org.

- ^ Baird, Julia (February 23, 2006). "The good and bad of religion-lite". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ "megachurch". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Ukah, Asonzeh (6 February 2020). "Chapter 15: Sacred Surplus and Pentecostal Too-Muchness: The Salvation Economy of African Megachurches". Handbook of Megachurches. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion, Volume 19. Brill. pp. 323–344. doi:10.1163/9789004412927_017. ISBN 9789004412927. S2CID 213645909. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ Maccotta, Lorenzo (7 December 2019). "Rise of Mega Churches in Sub Sahara". Cherrydeck. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ Taylor Berglund, World's Largest Church Auditorium Dedicated in Nigeria, charismanews.com, December 7, 2018

- ^ Miller, Duane A. "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census".

- ^ Viegas, Fátima (2008) Panorama das Religiões em Angola Independente (1975–2008), Ministério da Cultura/Instituto Nacional para os Assuntos Religiosos, Luanda

- ^ "Religions in Eritrea | PEW-GRF". www.globalreligiousfutures.org.

- ^ "Africa :: GABON". CIA The World Factbook. 17 February 2022.

- ^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 17 February 2022.

- ^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 17 February 2022.

- ^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 17 February 2022.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2010: Liberia". United States Department of State. November 17, 2010. Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 22 February 2022.

- ^ A. Lamport, Mark (2021). Encyclopedia of Christianity in the Global South. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 497. ISBN 9781442271579.

Influences—Christian influences in Mauritanian society are limited to the approximately 10,000 foreign nationals living in the country

- ^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 18 February 2022.

- ^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 22 February 2022.

- ^ Dominique Lewis (May 2013). "Nigeria Round 5 codebook (2012)" (PDF). Afrobarometer. p. 62. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 14 February 2022.

- ^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 22 February 2022.

- ^ "The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ "Almost expunged: Somalia's Embattled Christians". 2009-10-22. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- ^ StatsSA National Census results 2012 http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/SAStatistics/SAStatistics2012.pdf

- ^ "Table: Religious Composition by Country, in Numbers". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 18 December 2012. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ^ "Table: Religious Composition by Country, in Percentages". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 18 December 2012. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ^ "The World Factbook". cia.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- ^ "CIA Site Redirect — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 22 February 2022.

- ^ a b Office of International Religious Freedom (12 May 2021). "2020 Report on International Religious Freedom: Tunisia". US Department of State. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ Zambia - 2010 Census of Population and Housing Archived 2016-01-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Religious composition by country Archived 2018-02-19 at the Wayback Machine, Pew Research, Washington DC (2012)

- ^ The Global Catholic Population, Pew Research CenterReligion & Public Life

- ^ Timothy, D.J. (2023). Cultural Heritage and Tourism in Africa. Routledge Cultural Heritage and Tourism Series. Taylor & Francis. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-000-83438-3. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ Zook, M.S.; Haude, S. (2016). Challenging Orthodoxies: The Social and Cultural Worlds of Early Modern Women: Essays Presented to Hilda L. Smith. Taylor & Francis. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-317-16875-1. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ The Catholic Explosion Archived 2011-11-14 at the Wayback Machine, Zenit News Agency, 11 November 2011

- ^ Rachel Donadio, "On Africa Trip, Pope Will Find Place Where Church Is Surging Amid Travail," New York Times, 16 March 2009.

- ^ "Orthodox Christianity in the 21st Century". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 8 November 2017.

Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church has an estimated 36 million adherents, nearly 14% of the world's total Orthodox population.

- ^ Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Population Census Commission (4 June 2012). "Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census Results" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2012.

- ^ "Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church | church, Ethiopia". Encyclopedia Britannica. 23 January 2024.

In the early 21st century the church claimed more than 30 million adherents in Ethiopia.

- ^ "Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church — World Council of Churches". www.oikoumene.org. January 1948.

- ^ "Ethiopia: An outlier in the Orthodox Christian world". Pew Research Center. 28 November 2017.

- ^ "Orthodox Christianity in the 21st Century". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 8 November 2017.

Egypt has the Middle East's largest Orthodox population (an estimated 4 million Egyptians, or 5% of the population), mainly members of the Coptic Orthodox Church.

- ^ "BBC - Religions - Christianity: Coptic Orthodox Church". BBC.

The Coptic Orthodox Church is the main Christian Church in Egypt, where it has between 6 and 11 million members.

- ^ Matt Rehbein (10 April 2017). "Who are Egypt's Coptic Christians?". CNN.

- ^ "Coptic Orthodox Church — World Council of Churches". www.oikoumene.org. January 1948.

- ^ "Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church — World Council of Churches". www.oikoumene.org. January 2003.

- ^ "Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria and All Africa — World Council of Churches". www.oikoumene.org. January 1948. Archived from the original on 6 October 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Sallam, HN; Sallam, NH (2016-03-03). "Religious aspects of assisted reproduction". Facts, Views & Vision in ObGyn. 8 (1). Vlaamse Vereniging voor Obstetrie en Gynaecologie: 33–48. PMC 5096425. PMID 27822349.

- ^ https://ijmra.in/v6i9/Doc/34.pdf. Retrieved 2024-12-02.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Piper, J.; Grudem, W. (2006). Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism. Crossway. p. 421. ISBN 978-1-4335-1918-5. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ Hutchinson, M.; Wolffe, J. (2012). A Short History of Global Evangelicalism. Cambridge University Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-107-37689-2. Retrieved 2024-10-03.

- ^ "In Africa, Pope Francis will find religious vibrancy and violence". 24 November 2015.

- ^ "The phenomenal rise of Christians in Africa". 3 January 2012.

- ^ Jeffrey, G.R. (2008). The Next World War: What Prophecy Reveals about Extreme Islam and the West. Crown Publishing Group. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-307-44619-0. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ "Protestant Countries 2022".

- ^ Bongmba, E.K. (2012). The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to African Religions. Wiley Blackwell Companions to Religion. Wiley. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-118-25554-4. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ Roper, L. (2023). Living I Was Your Plague: Martin Luther's World and Legacy. The Lawrence Stone Lectures. Princeton University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-691-20532-8. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ a b Zurlo, G. (2022). Global Christianity: A Guide to the World's Largest Religion from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. Zondervan Academic. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-310-11363-8. Retrieved 2024-12-02.

- ^ Wainwright, G.; McPartlan, P. (2021). The Oxford Handbook of Ecumenical Studies. Oxford Handbooks. Oxford University Press. p. 512. ISBN 978-0-19-960084-7. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ Yrigoyen, C.; Warrick, S.E. (2013). Historical Dictionary of Methodism. Historical Dictionaries of Religions, Philosophies, and Movements Series. Scarecrow Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8108-7894-5. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ Vaux, K.L. (2013). For Such a Time as This: Evanston Killings, Election, Ethics Consult. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-62189-812-2. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ^ "Church of Nigeria". Anglican-nig.org. 18 April 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Church of Uganda". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on February 12, 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Anglican Church of Kenya". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Episcopal Church of the Sudan". www.oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008.

- ^ "Anglican Church of Southern Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Anglican Church of Tanzania". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Province of the Episcopal Church in Rwanda". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Church of the Province of Central Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Anglican Church of Burundi". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Church of Christ in Congo – Anglican Community of Congo". Oikoumene.org. 20 December 2003. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Church of the Province of West Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "South African Christian". Sachristian.co.za. Archived from the original on 20 June 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Baptist World Alliance - Statistics". www.bwanet.org. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ Nyika, Felix Chimera (2008). Restore the Primitive Church Once More: A Survey of Post Reformation Christian Restorationism. Kachere Series. p. 14.

In the 1990s the New Apostolic Church had almost 300 apostles with 60,000 congregations comprising 16 million members globally.

- ^ Kuligin, Victor (2005). "The New Apostolic Church". Africa Journal of Evangelical Theology. 24 (1): 1–18.

- ^ "Member Churches". 19 May 2013.

- ^ "Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus". News and Events. EECMY. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ "Tanzania | The Lutheran World Federation". www.lutheranworld.org. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ "Madagascar | The Lutheran World Federation". www.lutheranworld.org. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ "Nigeria | The Lutheran World Federation". www.lutheranworld.org. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Namibia | The Lutheran World Federation". www.lutheranworld.org. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ "South Africa | The Lutheran World Federation". www.lutheranworld.org. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ "Cameroon | The Lutheran World Federation". www.lutheranworld.org. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ "Zimbabwe | The Lutheran World Federation". www.lutheranworld.org. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Resource: More Methodist Maps". 5 April 2018.

- ^ "Methodist Church Nigeria". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Methodist Church of Southern Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "United Methodist Church of Ivory Coast". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Methodist Church Ghana". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Methodist Church in Kenya". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Democratic Republic of Congo | Official Free Methodist World Missions".

- ^ "Presbyterian Church of East Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Presbyterian Church of Nigeria". Oikoumene.org. January 1961. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ "Presbyterian Church of Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Church of Christ in Congo – Presbyterian Community of Congo". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Presbyterian Church of Cameroon". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Patrick Johnstone and Jason Mandryk, Operation World: 21st Century Edition (Paternoster, 2001), p. 419 Archived 31 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Presbyterian Church of the Sudan". www.oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011.

- ^ "Presbyterian Church in Cameroon". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Presbyterian Church of Ghana". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Uniting Presbyterian Church in Southern Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Presbyterian Church in Rwanda". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Church of Jesus Christ in Madagascar (FJKM)". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "United Church of Zambia". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Administrator. "Qui sommes-nous?". Eeccameroun.org. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Lesotho Evangelical Church". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Reformed Church of Christ in Nigeria". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 September 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Reformed Church in Zambia". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Evangelical Reformed Church of Angola". Oikoumene.org. January 1995. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ "The Church of Christ in the Sudan among the Tiv (NKST)". Recweb.org. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Evangelical Church of Congo". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Evangelical Congregational Church in Angola". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "United Congregational Church of Southern Africa". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Wariboko, Nimi (2017). "Pentecostalism in Africa". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.120. ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4.

- ^ Soeffner, H.G. (2012). Transnationale Vergesellschaftungen: Verhandlungen des 35. Kongresses der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie in Frankfurt am Main 2010. Herausgegeben in deren Auftrag von Hans-Georg Soeffner. SpringerLink : Bücher (in German). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. p. 67. ISBN 978-3-531-18971-0. Retrieved 2024-10-03.

- ^ "About us", Ethiopian Kale Heywet Church. Retrieved 9 May 2020

- ^ Ethiopian Full Gospel Believers' Church, Overview of EMWACDO Archived 2019-09-20 at the Wayback Machine, etfullgospel.org, Ethiopia, retrieved September 17, 2019

- ^ "About Assemblies of God Nigeria". Archived from the original on 2019-03-08. Retrieved 2020-01-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Meserete Kristos College Newsletter (December 2014): 3.

- ^ Sanneh, L.; McClymond, M. (2016). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to World Christianity. Wiley Blackwell Companions to Religion. Wiley. p. 666. ISBN 978-1-118-55604-7. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ Gordon Melton. "African Initiated Churches". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ "Redemption Camp | Armin Rosen". First Things. January 2018. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ "Church of the Lord (Aladura) Worldwide". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Council of African Instituted Churches". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Church of Christ Light of the Holy Spirit". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "African Church of the Holy Spirit". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 9 September 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "African Israel Nineveh Church". Oikoumene.org. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Statistics and Church Facts | Total Church Membership".

Further reading

[edit]- Cinnamon, John M. "Missionary expertise, social science, and the uses of ethnographic knowledge in colonial Gabon." History in Africa 33 (2006): 413-432. online[permanent dead link]

- Froise, Marjorie. Southern Africa : a factual portrait of the Christian Church in South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia and Swaziland (1989) online

- Froise, Marjorie. World Christianity : South Central Africa : a factual portrait of the Christian church (1991) online

- Hastings, Adrian. A history of African Christianity, 1950-1975 (Cambridge University Press, 1979).

- Hastings Adrian. Church and mission in modern Africa (1967) online

- Hastings Adrian. The Church in Africa, 1450–1950 (Clarendon, 1995). online

- Isichei, Elizabeth (22 February 1995). A History of Christianity in Africa: From Antiquity to the Present. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4674-2081-5.

- Lamport, Mark A. ed. Encyclopedia of Christianity in the global south (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018)

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott. The Great Century: North Africa and Asia 1800 A.D. to 1914 A.D. (A History of The Expansion of Christianity, Volume 5) (1943), Comprehensive scholarly coverage. full text online also online review;

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1944). The Great Century In Northern Africa And Asia AD 1800 AD 1914 Volume VI in A history of the expansion of Christianity. Retrieved 8 May 2024. online review

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott. The twentieth century outside Europe : the Americas, the Pacific, Asia, and Africa : the emerging world Christian community (1962) online

- Meyer, Birgit. "Christianity in Africa: From African independent to Pentecostal-charismatic churches." Annual Review of Anthropology 33 (2004): 447-474. online

- Neill, Stephen. A History of Christian Missions (1986), Global coverage over 19 centuries in 624 pages; online book also see. online review

- Ranger, T.O. and John Weller, eds. Themes in the Christian history of Central Africa (1975) online

Historiography and memory

[edit]- Bongmba, Elias Kifon. "Writing African Christianity: Perspectives from the History of the Historiography of African Christianity." Religion and Theology 23.3-4 (2016): 275-312. online[permanent dead link]

- Etherington. Norman. "Recent Trends in the Historiography of Christianity in Southern Africa" in Critical Readings in The History of Christian Mission: volume 3" ed by Martha Frederiks and Dorottya Nagy. (Brill, 2021) pp 39–66.

- Hastings, Adrian. "African Christian studies, 1967-1999: Reflections of an editor." Journal of religion in Africa 30#1 (2000): 30-44. online

- Maluleke, Tinyiko Sam. "The Quest for Muted Black Voices in History: Some Pertinent Issues in (South) African Mission Historiography" in Critical Readings in The History of Christian Mission: volume 3" ed by Martha Frederiks and Dorottya Nagy. (Brill, 2021) pp 95–115.

- Maxwell, David. "Writing the history of African Christianity: Reflections of an editor." Journal of religion in Africa 36.3-4 (2006): 379-399.