East Malaysia

East Malaysia (Malay: Malaysia Timur), or the Borneo States,[1] also known as Malaysian Borneo, is the part of Malaysia on and near the island of Borneo, the world's third-largest island. East Malaysia comprises the states of Sabah, Sarawak, and the Federal Territory of Labuan. The small independent nation of Brunei comprises two enclaves in Sarawak. To the south and southeast is the Indonesian portion of Borneo, Kalimantan.[2] East Malaysia lies to the east of Peninsular Malaysia (also known as the States of Malaya), the part of the country on the Malay Peninsula. The two are separated by the South China Sea.[3][4]

East Malaysia is less populated and has fewer developed settlements than West Malaysia. While West Malaysia contains the country's major cities (Kuala Lumpur, Johor Bahru, and Georgetown), East Malaysia is larger and much more abundant in natural resources, particularly oil and gas reserves. In the pan-regional style, city status is reserved for only a few settlements, including Kuching, Kota Kinabalu and Miri. Various other significant settlements are classified as towns, including many with over 100,000 residents. East Malaysia includes a significant portion of the biodiverse Borneo lowland rain forests and Borneo montane rain forests.

States and territories

[edit]East Malaysia or the Borneo States comprise 2 of the 13 states, and one out of the three federal territories of Malaysia.

History

[edit]Some parts of present-day East Malaysia, especially the coastal regions, were once part of the thalassocracy of the Sultanate of Brunei.[5] However, most parts of the interior region consisted of independent tribal societies.[6]

In 1658, the northern and eastern coasts of Sabah were ceded to the Sultanate of Sulu while the west coast of Sabah and most of Sarawak remained part of Brunei.[7] In 1888, Sabah and Sarawak together with Brunei became British protectorates.[8] In 1946, they became separate British colonies.[9][10]

Federation

[edit]Sabah (formerly British North Borneo) and Sarawak were separate British colonies from Malaya, and did not become part of the Federation of Malaya in 1957. Later on however, the then Federation merged with the self-governing State of Singapore and the British Colonies of North Borneo (now known as Sabah) and Sarawak under the Malaysia Agreement as the States of Malaya, the Borneo States of Sabah and Sarawak, and the State of Singapore of the new Federation called Malaysia on 16 September 1963, now known as Malaysia Day. Singapore left the Federation two years later in 1965 after being expelled[11] by then the Prime Minister of Malaysia, Tunku Abdul Rahman. Previously, there were efforts to unite Brunei, Sabah, and Sarawak under the North Borneo Federation but that failed after the Brunei Revolt occurred.

The Borneo States retained a higher degree of local government and legislative autonomy than the States of Malaya. For example, both states have their own immigration controls, requiring Malaysian citizens from West Malaysia to carry passports or identity cards when visiting East Malaysia.

The islands of Labuan were once part of North Borneo in 1946 before becoming a Federal Territory in Malaysia on 16 April 1984. It was used to establish a centre for offshore finance in 1990.

Since 2010, there has been some speculation and discussion, at least on the ground level, about the possibility of secession from the Federation of Malaysia[12] because of allegations of resource mishandling, illegal processing of immigrants, etc.[13]

Administration

[edit]The Borneo States of Sabah and Sarawak joined the Federation of Malaysia as equal partners with Malaya and Singapore. Sabah and Sarawak retained their rights covered under the Malaysia Agreement of 1963 and their degree of autonomy compared to the other states in Peninsular Malaysia. For example, the Malaysian Borneo States have separate laws regulating the entry of citizens from other states in Malaysia (including the other East Malaysian state), whereas, in Peninsular Malaysia, there are no restrictions on interstate travel or migration, including visitors from East Malaysia. There are also separate land laws governing Sabah and Sarawak, as opposed to the National Land Code, which governs Peninsular Malaysia.

In December 2021, constitutional amendments were passed to restore the status of Sabah and Sarawak as equal partners to Malaya, with 199 members of Parliament backing the amendment bill without opposition. Apart from restoring Article 1(2) to its pre-1976 wording, the bill defines Malaysia Day for the first time and redefines the federation with the inclusion of Malaysia Agreement (MA63). Previously, only Merdeka Day (independence day of the Federation of Malaya) was defined, and the federation was defined merely by the Malaya Agreement 1957.[14] The Constitution (Amendment) Act 2022 received royal assent on 19 January 2022 and came into force on 11 February 2022.[15][16]

With regard to the administration of justice, the courts in East Malaysia are part of the federal court system in Malaysia. The Constitution of Malaysia provides that there shall be two High Courts of co-ordinate jurisdiction.[17] The High Court in Malaya and the High Court in Sabah and Sarawak (formerly the High Court in Borneo). The current Chief Judge of Sabah and Sarawak is Abang Iskandar Abang Hashim from Sarawak. His office is the fourth highest in the Malaysian judicial system (behind the Chief Judge of Malaya, President of the Court of Appeal, and Chief Justice of Malaysia).

Politics

[edit]Compared to West Malaysia, political parties in Sarawak and Sabah started relatively late. This first political party in Sarawak emerged in 1959 while the first political party in Sabah emerged in August 1961. Sarawak held its first local authorities election in 1959 and did not have any directly elected legislature until 1970. Sabah only held its first district council election in December 1962 and first direct election in April 1967. Both the states were new and had little experience in organised, competitive politics. Therefore, there had been the appearance and rapid disappearance of political parties in Sarawak and Sabah within a short period of time, with some parties took opportunistic moves to form alliances without a definite loyalty to a certain political alignment. The ethnic composition of East Malaysia is also different from West Malaysia. The indigenous people in both Sarawak and Sabah do not form an absolute majority, while the non-native population in East Malaysia mainly consisting of entirely Chinese. Political parties in Sarawak and Sabah were formed largely based on communal lines and can be categorised roughly into native non-Muslim, native Muslim, and non-native parties. With the support of the Malaysia federal government, native Muslim parties in Sabah and Sarawak were strengthened. In Sabah, the native Muslim party United Sabah National Organisation (USNO) first clinged on the chief minister post in 1965 and later consolidated its power in 1967. In Sarawak, native Muslim party named Parti Bumiputera (which later regrouped into Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu (PBB) held the chief minister post since 1970.[18]

In 1976, all the Sabah and Sarawak MPs (except 4 absentees) supported the Malaysian parliament bill which downgraded both the states from being equal partners to Malaya as a whole, to one of the 13 states in the federation.[19]

Since 2008, East Malaysia played a more significant role in the national political landscape. The loss of two-thirds majority of Barisan Nasional (BN) government in the West Malaysia caused the BN to rely on East Malaysian politicians to cling on power.[20] After the conclusion of 2013 Malaysian general election, there was an increase in ministers and deputy ministers allocation for East Malaysia in the Malaysian Cabinet from 11 out of 57 portfolios in 2008 election to 20 out of 61 portfolios.[21][22] There had been no prime minister or deputy prime minister coming from East Malaysia until 2022,[23][24] when Fadillah Yusof became the first deputy prime minister from East Malaysia.[25] On several occasions, the federal government chaired its weekly cabinet meetings in Kuching instead of Putrajaya.[26][27]

As of 2012, Sarawak, Sabah and Labuan held a total of 57 out 222 seats (25.68%) in the Malaysian parliament.[28] Since 2014, Sarawak have been actively seeking for devolution of powers from the Malaysian federal government.[29] In October 2018, both Sabah and Sarawak chief ministers met to discuss common goals in demanding from the Malaysian federal government regarding the rights stipulated inside the Malaysia Agreement.[30] In December 2021, constitutional amendments were passed to restore the status of Sabah and Sarawak as equal partners to Malaya, with 199 members of Parliament backing the amendment bill without opposition. Apart from restoring Article 1(2) to its pre-1976 wording, the bill defines Malaysia Day for the first time and redefines the federation with the inclusion of Malaysia Agreement (MA63). Previously, only Merdeka Day (independence day of the Federation of Malaya) was defined, and the federation was defined merely by the Malaya Agreement 1957.[14] The Constitution (Amendment) Act 2022 received royal assent on 19 January 2022 and came into force on 11 February 2022.[15][16]

Physical geography

[edit]

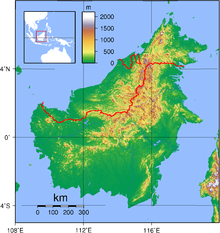

The landscape of East Malaysia is mostly lowland rain forests with areas of mountain rain forest towards the hinterland.

The total area of East Malaysia is 198,447 km2, representing approximately 60% of the total land area of Malaysia and 26.4% of the total area of Borneo, which is 50% bigger than Peninsular Malaysia at 132,490 square kilometres (51,150 sq mi), comparable with South Dakota or Great Britain.

East Malaysia contains the five highest mountains in Malaysia, the highest being Mount Kinabalu at 4095 m, which is also the highest mountain in Borneo and the 10th highest mountain peak in Southeast Asia. It also contains the two longest rivers in Malaysia – Rajang River and Kinabatangan River.[31]

Banggi Island in Sabah and Bruit Island in Sarawak are the two largest islands that are located entirely within Malaysia.[31] The largest island is Borneo, which is shared with Indonesia and Brunei.[32] The second largest island is Sebatik Island, in Sabah, which is shared with Indonesia.[33][34]

Sarawak contains the Mulu Caves within Gunung Mulu National Park. Its Sarawak Chamber is the largest (by area) known cave chamber in the world. The Gunung Mulu National Park was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in November 2000.[35]

Sabah's attractions include World Heritage Site Kinabalu Park (which includes Mount Kinabalu),[36] and Sipadan Island (a diving and bio-diversity hot-spot).[37]

Geology

[edit]Several oil and gas fields have been discovered offshore, including the Samarang oil field (1972) offshore Sabah, the Baronia oil field (1967) offshore Sarawak, and the Central Luconia natural gas fields (1968), also offshore Sarawak.[38] The Baronia Field is a domal structural trap between two east–west growth faults, which produces from late Miocene sandstones interbedded with siltstones and clays at 2 km depth in 75 m of water.[38]: 431 The Samarang Field produces from late Miocene sandtones in an alternating sequence of sandstones, siltstones and clays in an anticline at a depth of about 3 km in water 9–45 m.[38]: 431 The Central Luconia Gas Fields produce from middle to late Miocene carbonate platform and pinnacle reefs from 1.25 to 3.76 km deep and water depths 60-100m.[38]: 436–437

Population

[edit]Ethnicity in East Malaysia (as of 2010)

The total population of East Malaysia in 2010 was 5.77 million (3.21 million in Sabah, 2.47 million in Sarawak, and 0.09 million in Labuan),[39] which represented 20.4% of the population of Malaysia. A significant part of the population of East Malaysia today reside in towns and cities. The largest city and urban centre is Kuching, which is also the capital of Sarawak and has a population of over 600,000 people. Kota Kinabalu is the second largest, and one of the most important cities in East Malaysia. Kuching, Kota Kinabalu, and Miri are the only three places with city status in East Malaysia. Other important towns include Sandakan and Tawau in Sabah, Sibu and Bintulu in Sarawak, and Victoria in Labuan. The 2020 estimated population is 6 million (3,418,785 in Sabah, 2,453,677 in Sarawak and 95,120 in Labuan).

The earliest inhabitants of East Malaysia were the Dayak people and other related ethnic groups such as the Kadazan-Dusun people. These indigenous people form a significant portion, but not the majority, of the population. For hundreds of years, there has been significant migration into East Malaysia and Borneo from many parts of the Malay Archipelago, including Java, the Lesser Sunda Islands, Sulawesi, and Sulu. More recently, there has been immigration from India and China.

The indigenous inhabitants were originally animists. Islamic influence began as early as the 15th century, while Christian influence started in the 19th century.

The indigenous inhabitants are generally partisan and maintain culturally distinct dialects of the Malay language, in addition to their own ethnic languages. Approximately over one-tenth of the population of Sabah and Labuan, and almost a quarter of the population of Sarawak, is composed of local Chinese communities. The local Malay/Muslims consists approximately 13.6% in East Malaysia, with over two-thirds of Malay/Muslims in East Malaysia resides in the state of Sarawak, predominantly found in the city of Kuching and the surrounding areas. While among Indian communities, unlike their fellows in Peninsular Malaysia where they are considered as one of the several major ethnic groups in Peninsula, their population in East Malaysia was quite tiny, consists just about 0.3%, with the majority of them resides in the urban areas such as Kota Kinabalu, Tawau, Labuan and Miri, in addition to Kuching.

However, the demography of Sabah has been altered dramatically with the alleged implementation of Project IC in the 1990s. Citizenships are alleged to be granted to immigrants from Indonesia and Philippines in order to keep the UMNO ruling party in power.[40] Royal Commission of Inquiry (RCI) has been conducted from 11 August 2012 to 20 September 2013. The outcome of the investigation was submitted to the prime minister on 19 May 2014.[41] The report was released on 3 December 2014 after 6 months delay. It stated that Project IC might have existed, which was responsible for a sudden spike in the state population. However, the report did not pinpoint any responsibility except for "corrupt officials" who took advantage of the system.[42]

Education

[edit]East Malaysia currently has two public universities, namely Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS) and Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS). Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM) also has branch campuses in both states. Labuan's own institution of higher education is Universiti Malaysia Sabah Labuan International Campus, which has a branch in Sepanggar Bay, Kota Kinabalu. All prospective university entrants from Sabah, Sarawak, and Labuan must sit the examinations of one matriculation college, Kolej Matrikulasi Labuan.

UCSI University, Sarawak Campus, University College of Technology Sarawak (UCTS) Tunku Abdul Rahman University College (Sabah campus), International University College of Technology Twintech (Sabah campus), and Open University Malaysia (Sabah campus) have local private university branch campuses in East Malaysia. Curtin University, Malaysia and Swinburne University of Technology Sarawak Campus are foreign university branch campuses in Sarawak.

There are 4 teacher training colleges (Malay: Maktab Perguruan) in Sarawak, and 4 teacher training colleges in Sabah.[43]

Transport

[edit]The Pan Borneo Highway connects Sabah, Sarawak, and Brunei. The road has been poorly maintained since it was built. The narrow road is dark at night without any street lights and there are many danger spots, sharp bends, blind spots, potholes, and erosion.[44] However, federal government funds have been allocated for the upgrade of the highway, which will be carried out in stages until completion in 2025.[45]

The major airports in East Malaysia are Kuching International Airport, Labuan Airport and Kota Kinabalu International Airport. Kota Kinabalu International Airport has also become the second largest airport in Malaysia, with an annual capacity of 12 million passengers – 9 million for Terminal 1 and 3 million for Terminal 2. There are frequent air flights by including Malaysia Airlines (MAS) and AirAsia between East Malaysia and Peninsular Malaysia. Other ports of entry to East Malaysia include Sibu Airport, Bintulu Airport, and Miri Airport in Sarawak, Sandakan Airport and Tawau Airport in Sabah. MAS also operates international flights to major cities in East Malaysia.[46]

The rural areas in Borneo can only be accessed by air or river boat. River transport is especially prevalent in Sarawak because there are many large and long rivers, with Rajang River being the most used. Rivers are used by boats and ferries for communications (i.e. mail) and passenger transport between inland areas and coastal towns. Timber is also transported via vessels and log carriers down the rivers of Sarawak.[46]

The Labuan Ferry operates boat express and vehicle ferries from Labuan Island to Sabah, Sarawak and Brunei.[47] Ferries have overtaken air travel as the chief transportation mode on and off the island.

Economy

[edit]Shipyards in Sabah and Sarawak build steel vessels for offshore supply, tug, barge and river ferries when compared to shipyards in Peninsular Malaysia that focus on building steel and aluminium vessels for the government as well as oil and gas companies. This makes the shipyards in Sabah and Sarawak more competitive and innovative in design, process and material, compared to the shipyards in peninsular Malaysia, where the big projects are dependent on government funding.[48]

Security

[edit]The state of Sabah has been subjected to attacks by Moro pirates and militants since the 1960s and intensification in 1985, 2000, 2013. The Eastern Sabah Security Zone (ESSZONE) and Eastern Sabah Security Command (ESSCOM) were established on 25 March 2013 to tighten security in the region. Since 2014, a 12-hour dusk-to-dawn curfew has been imposed on six Sabah east coast districts.[49]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Bill for 'Borneo states' instead of 'East Malaysia'". The Star. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Commission regulation Official Journal of the European Union

- ^ "Location". Malaysia Travel.org.uk. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ "Malay Peninsula". HarperCollins Publishers. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ Saunders, Graham E. (2002), A History of Brunei, RoutlegdeCurzon, p. 45, ISBN 9780700716982, retrieved 5 October 2009

- ^ Singh, Ranjit (2000). The Making of Sabah, 1865–1941: The Dynamics of Indigenous Society. University of Malaya Press. ISBN 978-983-100-095-3.

- ^ The Report: Sabah 2011. Oxford Business Group. 2011. p. 179. ISBN 9781907065361. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Charles, de Ledesma; Mark, Lewis; Pauline, Savage (2003). Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei. Rough Guides. p. 723. ISBN 978-1-84353-094-7. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

In 1888, the three states of Sarawak, Sabah, and Brunei were transformed into protectorates, a status which handed over the responsibility for their foreign policy to the British in exchange for military protection.

- ^ Porritt, Vernon L. (1997). British Colonial Rule in Sarawak, 1946–1963. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-983-56-0009-8. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ^ "British North Borneo Becomes Crown Colony". Kalgoorlie Miner. Trove. 18 July 1946. p. 1. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ "Singapore History". eresources.nlb.gov.sg. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Push for Sabah, S'wak's independence: Next stop UN Archived 7 September 2012 at archive.today. Malaysia-today.net (2010-04-02). Retrieved on 2013-07-29.

- ^ Sarawak Watch [dead link]

- ^ a b "Dewan Rakyat finally passes key constitutional amendments to recognise MA63". Malay Mail. 14 December 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Constitution (Amendment) Act 2022 (Act A1642)". Federal Legislation Portal, Attorney General's Chambers (Malaysia). Archived from the original on 17 September 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Amendments to federal constitution come into force Friday - Wan Junaidi". Bernama. 11 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ "Malaysia | Standing International Forum of Commercial Courts". sifocc.org. Archived from the original on 8 November 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ R.S., Milne; K.J., Ratnam (2014). Malaysia: New States in a New Nation. Routledge. pp. 69–72. ISBN 978-1-135-16061-6. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ Chia, Jonathan (19 October 2016). "All round aye from Sabah, Sarawak". The Borneo Post. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ Meredith, L Weiss (17 October 2014). Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Malaysia. Routledge. p. 89. ISBN 9781317629597. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "20 ministers, deputy ministers from East Malaysia". Sin Chew Daily. 16 May 2013. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ "The new cabinet, by party and in numbers". Malaysiakini. 15 May 2013. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ Chieh, Yow Hong (27 October 2011). "East Malaysian DPM gratuitous, says Dr M". The Malaysian Insider. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ "Appoint DPMs from East M'sia, Putrajaya urged". Malaysiakini. 15 June 2014. Archived from the original on 16 June 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ "Profile: Fadillah Yusof creates history as first East Malaysian appointed DPM". New Straits Times. 3 December 2022. Archived from the original on 15 September 2023. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- ^ Pei Pei, Goh (4 May 2016). "PM Najib chairs cabinet meeting in Kuching". New Straits Times. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ "PM Anwar chairs cabinet meeting in Kuching". The Borneo Post. 16 September 2023. Archived from the original on 17 September 2023. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ Rintod, Luke (8 March 2012). "'Sabah, Sarawak's 'right' to have more parliament seats'". Free Malaysia Today. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ Harding, Andrew (December 2017). "Devolution of Powers in Sarawak: A Dynamic Process of Redesigning Territorial Governance in a Federal System". Asian Journal of Comparative Law. 12 (2): 257–279. doi:10.1017/asjcl.2017.13. ISSN 2194-6078. S2CID 158009054.

- ^ Sharon, Ling (11 October 2018). "Sabah and Sarawak CMs meet, have common goals over Malaysian Agreement 1963". The Star (Malaysia). Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ a b Geography, Malaysiahistorical.com.my, archived from the original on 27 April 2010, retrieved 16 July 2010

- ^ "Motorcycle tour description and itinerary for the Borneo-East Malaysia motorcycle tour". Asian Bike Tour. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ^ "Dive The Kakaban Island". De 'Gigant Tours. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ^ "Sebatik Island off Sabah, Malaysia 1965". The Band of Her Majesty's Royal Marines. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ^ "Gunung Mulu National Park". UNESCO.org. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ^ "Kinabalu Park". UNESCO.org. Archived from the original on 14 June 2010. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ^ Noreen (10 January 2010). "Diving at Sipadan Island, Borneo – An Untouched Piece of Art". Aquaviews: Online Scuba Magazine. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ^ a b c d Scherer, F.C., 1980, Exploration in East Malaysia Over the Past Decade, in Giant Oil and Gas Fields of the Decade, AAPG Memoir 30, Halbouty, M.T., editor, Tulsa, American Association of Petroleum Geologists, ISBN 0891813063, p. 424

- ^ "Chart 3: Population distribution by state, Malaysia, 2010" (PDF). Population Distribution and Basic Demographic Characteristics 2010 (in Malay and English). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. p. 2 (p. 13 in PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ "SPECIAL REPORT: Sabah's Project M (subscription required)". Malaysiakini. 27 June 2006. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "RCI report on Sabah's illegal immigrants handed to PM, Agong". The Malay Mail. 19 May 2014. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ Chi, Melissa (3 December 2014). "'Corrupt officials' blamed for Sabah problems, but RCI says hands tied". The Malay Mail. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ "Institut Pendidikan Guru (Teachers' Training Institute)". Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia (Malaysian Ministry of Education). Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

IPG Kampus Sarawak, IPG Kampus Tun Abdul Razak, IPG Kampus Batu Lintang(1st page), IPG Kampus Rajang (2nd page)

- ^ Then, Stephen (13 September 2013). "Repair Pan Borneo Highway now, says Bintulu MP following latest fatal accident". The Star. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Pan Borneo Highway project will be carried out in stages, says minister". The Star. 14 November 2013. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Getting To Borneo By Air, By Car, By Train". Asia Web Direct. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "New Ferry launched for Labuan-Sabah-Brunei sea route". The Star. 2 May 2015. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015.

- ^ van der Heide, Egide (2018). Port Development in Malaysia: An Introduction to the Country's Evolving Port Landscape (PDF). Kingdom of the Netherlands: Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Malaysia. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Chan, Julia (5 November 2014). "Sabah curfew renewed for the seventh time". The Malay Mail. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Andrew Harding & James Chin, 50 years of Malaysia: Archived 13 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine Federalism revisited (Marshall Cavendish 2014)

- James Chin The 1963 Malaysia Agreement (MA63): Sabah And Sarawak and the Politics of Historical Grievances (Amsterdam University Press, 2919)

- Cabinet Memorandum. Policy in regard to Malaya and Borneo. Memorandum by the Secretary of State for the Colonies. 29 August 1945

- Manila Accord (31 July 1963)

- Exchange of notes constituting an agreement relating to the implementation of the Manila Accord of 31 July 1963

- Acts of the Parliament of the United Kingdom Malaysia Act 1963

- Agreement relating to Malaysia between United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Federation of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore

External links

[edit]- Virtual Malaysia Archived 24 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine – The Official Portal of the Ministry of Tourism, Malaysia

- mulucaves.org Mulu Caves Project