East China Sea EEZ disputes

There are disputes between China, Japan, Taiwan and South Korea over the extent of their respective exclusive economic zones (EEZs) in the East China Sea.

The dispute between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and Japan concerns the different application of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which both nations have ratified.[1] China proposed the application of UNCLOS, considering the natural prolongation of its continental shelf, advocating that the EEZ extends as far as the Okinawa Trough.[2][3] Its Ministry of Foreign Affairs has stated that "the natural prolongation of the continental shelf of China in the East China Sea extends to the Okinawa Trough and beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of China is measured,"[2] which is applicable to the relevant UNCLOS provisions that support China's right to the natural shelf.[2][3]

In 2012, China presented a submission under the UNCLOS concerning the outer limits of the continental shelf to the UN.[4] Japan, based on UNCLOS, proposed the Median line division of the EEZ.[5]

Under the United Nations' Law of the Sea, the PRC claims the disputed ocean territory as its own Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) due to its being part of PRC's natural extension of its continental shelf, while Japan claims the disputed ocean territory as its own EEZ because it is within 200 nautical miles (370 km) from Japan's coast, and proposed a median line as the boundary between the EEZ of China and Japan. About 40,000 square kilometres (15,000 square miles) of EEZ are in dispute. China and Japan both claim 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) of EEZ rights, but the East China Sea width is only 360 nautical miles (670 km; 410 mi). China claims an EEZ extending to the eastern end of the Chinese continental shelf (based on UNCLOS III) which goes deep into the Japanese's claimed EEZ.[6]

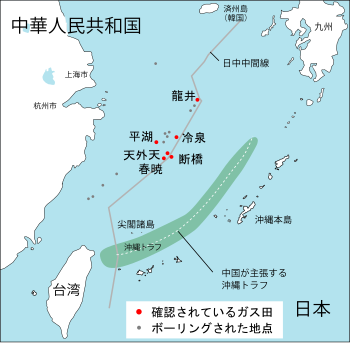

In 1995, the People's Republic of China (PRC) discovered an undersea natural gas field in the East China Sea, namely the Chunxiao gas field,[7] which lies within the Chinese EEZ while Japan believes it is connected to other possible reserves beyond the median line.[8] Japan has objected to PRC development of natural gas resources in the East China Sea near an area where the two countries Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) claims overlap. The specific development in dispute is the PRC's drilling in the Chunxiao gas field, which is located in undisputed areas on China's side, three or four miles (6 km) west of the median line proposed by Japan. Japan maintains that although the Chunxiao gas field rigs are on the PRC side of a median line that Tokyo regards as the two sides' sea boundary, they may tap into a field that stretches underground into the disputed area.[9] Japan therefore seeks a share in the natural gas resources. The gas fields in the Xihu Sag area in the East China Sea (Canxue, Baoyunting, Chunxiao, Duanqiao, Wuyunting, and Tianwaitian) are estimated to hold proven reserves of 364 BCF of natural gas. Commercial operations began 2006. In June 2008, both sides agreed to jointly develop the Chunxiao gas fields.[9][10]

Rounds of disputes about island ownership in the East China Sea have triggered both official and civilian protests between China and Japan.[11]

The dispute between PRC and South Korea concerns Socotra Rock, a submerged reef on which South Korea has constructed a scientific research station. While neither country claims the rock as territory, the PRC has objected to Korean activities there as a breach of its EEZ rights.[12]

South Korea opened a museum in central Seoul in 2012 to back its claim to the Liancourt Rocks. Visitors can walk around a large 3-D model of the island and examine video and computerized content on the island's history and nature. Video screens show live footage of the island from a fixed camera. In January 2018 the Japanese government opened a small museum in Tokyo displaying maps and documents to defend its territorial claims against neighboring South Korea and China.[13]

See also

[edit]- Chinese imperialism

- Territorial disputes of Japan

- Territorial disputes of the People's Republic of China

References

[edit]- ^ Koo, Min Gyo (2009). Island Disputes and Maritime Regime Building in East Asia. Springer. pp. 182–183. ISBN 9781441962232.

- ^ a b c Wang, Yuanyuan (2012). "China to submit outer limits of continental shelf in East China Sea to UN". Xinhua. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012.

- ^ a b Guo, Rongxing (2006). Territorial Disputes and Resource Management: A Global Handbook. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc. p. 104. ISBN 9781600214455.

- ^ Yu, Runze (2012-12-15). "China reports to UN outer limits of continental shelf in E. China Sea". SINA English. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013.

- ^ "Diplomatic Bluebook 2006" (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. p. 43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-08.

- ^ Pike, John. "Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands". Globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 2004-11-17.

- ^ Kim, Sun Pyo (2004). Maritime Delimitation and Interim Arrangements in North East Asia. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 285. ISBN 9789004136694.

- ^ Bush, Richard C. (2010). The Perils of Proximity: China-Japan Security Relations. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. p. 76. ISBN 9780815704744.

- ^ a b Fackler, Martin (19 June 2008). "China and Japan in Deal Over Contested Gas Fields". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024.

- ^ Ersan, Yagmur (2013-07-25). "China, Japan conflict on Chunxiao/Shirakaba gas field". The Journal of Turkish Weekly. Archived from the original on January 25, 2014. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- ^ "Chinese, Japanese Stage Protests Over East China Sea Islands". Voice of America. 2008-10-15. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012.

- ^ You, Ki-Jun (19 March 2012). "Marine Scientific Research in Northeast Asia". In Nordquist, Myron H.; Moore, John Norton; Soons, Alfred H. A.; et al. (eds.). The Law of the Sea Conventions: US Accession and Globalization. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 499. ISBN 978-90-04-20136-1.

- ^ "Museum opens in Tokyo, displaying documents to defend claims to disputed isles". Japan Today. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

Further reading

[edit]- Chan, Steve. China's Troubled Waters: Maritime Disputes in Theoretical Perspective (Cambridge UP, 2016) excerpt

- Hawksley, Humphrey. Asian Waters: The Struggle Over the South China Sea and the Strategy of Chinese Expansion (2018) excerpt

- Peterson, Alexander M. "Sino-Japanese Cooperation in the East China Sea: A Lasting Arrangement?" 42 Cornell International Law Journal 441 (2009).

- Yea, Andy. "Maritime territorial disputes in East Asia: a comparative analysis of the South China Sea and the East China Sea." Journal of Current Chinese Affairs 40.2 (2011): 165–193. Online