Early history of fantasy

Elements of the supernatural and the fantastic were an element of literature from its beginning, though the idea of a distinct genre, in the modern sense, is less than two centuries old.

Ancient

[edit]Near East

[edit]The Epic of Gilgamesh was written over generations following the supposed reign of King Gilgamesh, and is seen as a mythologized version of his life. This figure is sometimes an influence and, more rarely, a figure in modern fantasy.[1]

Ancient India

[edit]India has a long tradition of fantastical stories and characters, dating back to Vedic mythology. Several modern fantasy works such as RG Veda draw on the Rig-Veda as a source. Hindu mythology was an evolution of the earlier Vedic mythology and had many more fantastical stories and characters, particularly in the Indian epics, such as the Mahabharata by Vyasa, and the Ramayana by Valmiki, both of which were influential in Asia. The Panchatantra (Fables of Bidpai) was influential in Europe and the Middle East. It used various animal fables and magical tales to illustrate the central Indian principles of political science. Talking animals endowed with human qualities have now become a staple of modern fantasy.[2]

The Baital Pachisi (Vikram and the Vampire) is a collection of various fantasy tales set within a frame story about an encounter between King Vikramāditya and a Vetala, an early mythical creature resembling a vampire. According to Richard Francis Burton and Isabel Burton, the Baital Pachisi "is the germ which culminated in the Arabian Nights, and which inspired the Golden Ass of Apuleius, Boccacio's Decamerone, the Pentamerone, and all that class of facetious fictitious literature."[3]

Greco-Roman

[edit]

Classical mythology is replete with fantastical stories and characters, the best known (and perhaps the most relevant to modern fantasy) being the works of Homer (Greek) and Virgil (Roman).[4]

The contribution of the Greco-Roman world to fantasy is vast and includes: The hero's journey (also the figure of the chosen hero); magic gifts donated to win (including the ring of power as in the Gyges story contained in the Republic of Plato), prophecies (the oracle of Delphi), monsters and creatures (especially Dragons), magicians and witches with the use of magic.[citation needed]

The philosophy of Plato has had great influence on the fantasy genre. In the Christian Platonic tradition, the reality of other worlds, and an overarching structure of great metaphysical and moral importance, has lent substance to the fantasy worlds of modern works.[5] The world of magic is largely connected with the Roman Greek world. With Empedocles, the elements, they are often used in fantasy works as personifications of the forces of nature.[6] Concerns other than magic include the use of a mysterious tool endowed with special powers (the wand); the use of a rare magical herb; and a divine figure that reveals the secret of the magical act.[citation needed]

Myths especially important for fantasy include: The myth of Titans; the Gods of Olympus; Pan; Theseus, the hero who killed the Minotaur (with the labyrinth); Perseus, the hero who killed Medusa ( with the gift of magic objects and weapons); Heracles is probably the best known Greek hero; Achilles; the riddling Sphinx; Odysseus; Ajax; Jason (of the Argonauts); Female sorcerers as well Circe, Calypso and goddess Hecate; Daedalus and Icarus.[citation needed]

Medieval

[edit]East Asia

[edit]The figures of Chinese dragons were influential on the modern fantasy use of the dragon, tempering the greedy, thoroughly evil, even diabolical Western dragon; many modern fantasy dragons are humane and wise.[citation needed]

Chinese traditions have been particularly influential in the vein of fantasy known as Chinoiserie, including such writers as Ernest Bramah and Barry Hughart.[7]

Taoist beliefs about neijin and its influence on martial arts have been a major influence on wuxia, a subgenre of the martial arts film that is sometimes fantasy, when the practice of wuxia is used fictitiously to achieve super-human feats, as in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.[8]

Islamic Middle East

[edit]

The most well known fiction from the Islamic world was The Book of One Thousand and One Nights (Arabian Nights), which was a compilation of many ancient and medieval folk tales. The epic took form in the tenth century and reached its final form by the fourteenth century; the number and type of tales have varied from one manuscript to another.[9] All Arabian fairy tales were often called "Arabian Nights" when translated into English, regardless of whether they appeared in The Book of One Thousand and One Nights, in any version, and a number of tales are known in Europe as "Arabian Nights" despite existing in no Arabic manuscript.[9]

This epic has been influential in the West since it was translated in the 18th century, first by Antoine Galland.[10] Many imitations were written, especially in France.[11] Various characters from this epic have themselves become cultural icons in Western culture, such as Aladdin, Sinbad and Ali Baba. Part of its popularity may have sprung from the increasing historical and geographical knowledge, so that places of which little was known and so marvels were plausible had to be set further "long ago" or farther "far away"; this is a process that continue, and finally culminate in the fantasy world having little connection, if any, to actual times and places.[citation needed]

A number of elements from Persian and Arabian mythology are now common in modern fantasy, such as genies, bahamuts, magic carpets, magic lamps, etc.[11] When L. Frank Baum proposed writing a modern fairy tale that banished stereotypical elements, he included the genie as well as the dwarf and the fairy as stereotypes to go.[12]

The Shahnameh, the national epic of Iran, is a mythical and heroic retelling of Persian history. Amir Arsalan was also a popular mythical Persian story.

Europe

[edit]

Medieval European sources of fantasy occurred primarily in epic poetry and in the Fornaldarsagas, Norse and Icelandic sagas, both of which are based on ancient oral tradition. The influence of these works on the German Romantics, as well as William Morris, and J. R. R. Tolkien means that their influence on later fantasy has been large.[13]

Anglo-Saxon

[edit]Beowulf is among the best known of the Nordic tales in the English speaking world, and has had deep influence on the fantasy genre; although it was unknown for centuries and so not developed in medieval legend and romance, several fantasy works have retold the tale, such as John Gardner's Grendel.[14]

Norse

[edit]Norse mythology, as found in the Elder Edda and the Younger Edda, includes such figures as Odin and his fellow Aesir, and dwarves, elves, dragons, and giants.[15] These elements have been directly imported into various fantasy works, and have deeply influenced others, both on their own and through their influence on Nordic sagas, Romanticism, and early fantasy writers.

The Fornaldarsagas, literally tales of times past, or Legendary sagas, occasionally drew upon these older myths for fantastic elements. Such works as Grettis saga carried on that tradition; the heroes often embark on dangerous quests where they fight the forces of evil, dragons, witchkings, barrow-wights, and rescue fair maidens.[16]

More historical sagas, such as Völsunga saga and the Nibelungenlied, feature conflicts over thrones and dynasties that also reflect many motifs commonly found in epic fantasy.[13]

The starting point of the fornaldarsagas' influence on the creation of the Fantasy genre is the publication, in 1825, of the most famous Swedish literary work Frithjof's saga, which was based on the Friðþjófs saga ins frœkna, and it became an instant success in England and Germany. It is said to have been translated twenty-two times into English, twenty times into German, and once at least into every European language, including modern Icelandic in 1866. Their influence on authors, such as J. R. R. Tolkien, William Morris and Poul Anderson and on the subsequent modern fantasy genre is considerable, and can perhaps not be overstated.[citation needed]

Celtic

[edit]

Celtic folklore and legend has been an inspiration for many fantasy works. The separate folklore of Ireland, Wales, and Scotland has sometimes been used indiscriminately for "Celtic" fantasy, sometimes with great effect; other writers have distinguished to use a single source.[17]

The Welsh tradition has been particularly influential, owing to its connection to King Arthur and its collection in a single work, the epic Mabinogion.[17] One influential retelling of this was the fantasy work of Evangeline Walton: The Island of the Mighty, The Children of Llyr, The Song of Rhiannon, and Prince of Annwn. A notable amount of fiction has been written in the area of Celtic fantasy.[18]

The Irish Ulster Cycle and Fenian Cycle have also been plentifully mined for fantasy.[17]

Scottish tradition is less used, perhaps because of the spurious nature of the Ossian cycle, a nineteenth-century fraud claiming to have much older sources.[17]

Its greatest influence was, however, indirect. Celtic folklore and mythology provided a major source for the Arthurian cycle of chivalric romance: the Matter of Britain. Although the subject matter was heavily reworked by the authors, these romances developed marvels until they became independent of the original folklore and fictional, an important stage in the development of fantasy.[19]

Finnish

[edit]The Finnish epic, the Kalevala, although not published until the 19th century, is compiled from oral tradition dating back to an earlier period. J. R. R. Tolkien cited it, with the Finnish language he learned from it, as a major inspiration behind the Silmarillion.[20]

Renaissance

[edit]

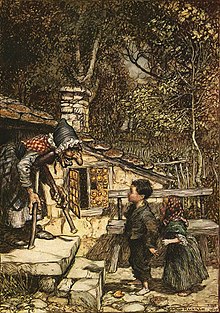

During the Renaissance, Giovanni Francesco Straparola wrote and published The Facetious Nights of Straparola, a collection of stories, many of which are literary fairy tales Giambattista Basile wrote and published the Pentamerone, a collection of literary fairy tales, the first collection of stories to contain solely the stories later to be known as fairy tales. Both of these works includes the oldest recorded form of many well-known (and more obscure) European fairy tales.[21] This was the beginning of a tradition that would both influence the fantasy genre and be incorporated in it, as many works of fairytale fantasy appear to this day.[22]

Although witchcraft and wizardry were both more commonly believed to be actual at the time, such motifs as the fairies in William Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, the Weird Sisters in Macbeth and Prospero in The Tempest (or Doctor Faustus in Christopher Marlowe's play) were deeply influential on later works of fantasy.[citation needed]

In a work on alchemy in the 16th century, Paracelsus identified four types of beings with the four elements of alchemy: gnomes, earth elementals; undines, water elementals; sylphs, air elementals; and salamanders, fire elementals.[23] Most of these beings are found in folklore as well as alchemy; their names are often used interchangeably with similar beings from folklore.[24]

The Enlightenment

[edit]

Literary fairy tales, such as those of Charles Perrault (1628 – 1703), and Madame d'Aulnoy (c.1650 – 1705), became popular early in the Age of Enlightenment. Many of Perrault's tales became fairy tale staples, and influenced latter fantasy as such. Indeed, when Madame d'Aulnoy termed her works contes de fée (fairy tales), she invented the term that is now generally used for the genre, thus distinguishing such tales from those involving no marvels.[25] This would influence later writers, who took up the folk fairy tales in the same manner, in the Romantic era.[26]

Several fantasies aimed at an adult readership were published in 18th century France, including Voltaire's "contes philosophique" "The Princess of Babylon" (1768) and "The White Bull" (1774), and Jacques Cazotte's Faustian novel The Devil in Love.[27]

This era, however, was notably hostile to fantasy. Writers of the new types of fiction such as Defoe, Richardson, and Fielding were realistic in style, and many early realistic works were critical of fantastical elements in fiction.[28] Aside from a few tales of witchcraft and ghost stories, very little fantasy was written during this time.[26] Even children's literature saw little fantasy; it aimed at edifying and deplored fairy tales as lies.[29]

Romanticism

[edit]

Romanticism, a movement of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, was a dramatic reaction to Rationalism, challenging the priority of reason and promoting the importance of imagination and spirituality. Its success in rehabilitating imagination was of fundamental importance to the evolution of fantasy, and its interest in medieval romances providing many motifs to modern fantasy.[30]

In the later part of the Romantic tradition, in reaction to the spirit of the Enlightenment, folklorists collected folktales, epic poems, and ballads, and brought them out in printed form. The Brothers Grimm were inspired in their collection, Grimm's Fairy Tales, by the movement of German Romanticism. Many other collectors were inspired by the Grimms and the similar sentiments. Frequently their motives stemmed not merely from Romanticism, but from Romantic nationalism, in that many were inspired to save their own country's folklore: sometimes, as in the Kalevala, they compiled existing folklore into an epic to match other nation's; sometimes, as in Ossian, they fabricated folklore that should have been there. These works, whether fairy tale, ballads, or folk epics, were a major source for later fantasy works.[31]

Despite the nationalistic elements confusing the collections, this movement not only preserved many instances of the folktales that involved magic and other fantastical elements, it provided a major source for later fantasy.[32] Indeed, the literary fairy tale developed so smoothly into fantasy that many later works (such as Max Beerbohm's The Happy Hypocrite and George MacDonald's Phantastes) that would now be called fantasies were called fairy tales at the time they written.[33] J. R. R. Tolkien's seminal essay on fantasy writing was titled "On Fairy Stories."

Ossian and the ballads also provided an influence to fantasy indirectly, through their influence on Sir Walter Scott, who began the genre of historical fiction.[34] Very few of his works contain fantastic elements; in most, the appearance of such is explained away,[35] but in its themes of adventure in a strange society, this led to the adventures set in foreign lands, by H. Rider Haggard and Edgar Rice Burroughs,[36] Although Burrough's works fall in the area of science fiction because of their (often thin) justifications for their marvels,[37] Haggard's included many fantastic elements.[38] The works of Alexandre Dumas, père, romantic historical fiction, contained many fantasy tropes in their realistic settings.[39] All of these authors influenced fantasy for the plots, characters and landscapes used—particularly in the sword and sorcery genre, with such writers as Robert E. Howard.[40]

References

[edit]- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Gilgamesh", p. 410. ISBN 0-312-19869-8.

- ^ Richard Matthews (2002). Fantasy: The Liberation of Imagination, p. 8–10. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93890-2.

- ^ Isabel Burton, Preface, in Richard Francis Burton (1870), Vikram and The Vampire.

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Taproot texts", p 921 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ Stephen Prickett, Victorian Fantasy p 229 ISBN 0-253-17461-9

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Elemental" p 313-4, ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Chinoiserie", p 189 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ Eric Yin, "A Definition of Wuxia and Xia"

- ^ a b John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Arabian fantasy", p 51 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ L. Sprague de Camp, Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy, p 10 ISBN 0-87054-076-9

- ^ a b John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Arabian fantasy", p 52 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ James Thurber, "The Wizard of Chitenango", p 64 Fantasists on Fantasy edited by Robert H. Boyer and Kenneth J. Zahorski, ISBN 0-380-86553-X

- ^ a b John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Nordic fantasy", p 692 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Beowulf", p 107 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Nordic fantasy", p 691 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Saga", p 831 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ a b c d John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Celtic fantasy", p 275 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ Michael Moorcock, Wizardry & Wild Romance: A Study of Epic Fantasy p 101 ISBN 1-932265-07-4

- ^ Colin Manlove, Christian Fantasy: from 1200 to the Present p 12 ISBN 0-268-00790-X

- ^ Tom Shippey, The Road to Middle-earth, p 242-243, ISBN 0-618-25760-8

- ^ Steven Swann Jones, The Fairy Tale: The Magic Mirror of Imagination, Twayne Publishers, New York, 1995, ISBN 0-8057-0950-9, p38

- ^ L. Sprague de Camp, Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy, p 11 ISBN 0-87054-076-9

- ^ Carole B. Silver, Strange and Secret Peoples: Fairies and Victorian Consciousness, p 38 ISBN 0-19-512199-6

- ^ C.S. Lewis, The Discarded Image, p135 ISBN 0-521-47735-2

- ^ Zipes, Jack David (2001). The Great Fairy Tale Tradition. W W Norton & Company. p. 858. ISBN 978-0-393-97636-6.

- ^ a b De Camp, Lyon Sprague (1976). Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers. Arkham House. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-87054-076-9.

- ^ Stableford, Brian (2009). The A to Z of Fantasy Literature. Scarecrow Press. p. xx. ISBN 978-0-8108-6829-8.

- ^ Carter, Lin (1976). Realms of Wizardry. Doubleday Books. pp. xiii–xiv. ISBN 9780385113939. OCLC 1345652143.

- ^ Lochhead, Marion (1977). The Renaissance of Wonder in Children's Literature. Canongate. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-903937-28-3.

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Romanticism", p 821 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ Michael Moorcock, Wizardry & Wild Romance: A Study of Epic Fantasy p 35 ISBN 1-932265-07-4

- ^ Philip Martin, The Writer's Guide to Fantasy Literature: From Dragon's Liar to Hero's Quest, pp. 38-42, ISBN 0-87116-195-8.

- ^ W.R. Irwin, The Game of the Impossible, p 92-3, University of Illinois Press, Urbana Chicago London, 1976

- ^ Michael Moorcock, Wizardry & Wild Romance: A Study of Epic Fantasy p 79 ISBN 1-932265-07-4

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Scott, (Sir) Walter", p 845 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ Michael Moorcock, Wizardry & Wild Romance: A Study of Epic Fantasy p 80-1 ISBN 1-932265-07-4

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Burroughs, Edgar Rice", p 152 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Haggard, H. Rider ", p 444-5 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Dumas, Alexandre père", p 300 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ^ Michael Moorcock, Wizardry & Wild Romance: A Study of Epic Fantasy p 82 ISBN 1-932265-07-4