Ealing

| Ealing | |

|---|---|

| |

Location within Greater London | |

| Population | 85,014 (2011 Census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TQ175805 |

| • Charing Cross | 7.5 mi (12.1 km) E |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | W5, W13 |

| Postcode district | NW10 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Ealing (/ˈiːlɪŋ/) is a district in West London, England, 7.5 miles (12.1 km) west of Charing Cross in the London Borough of Ealing.[2] It is the administrative centre of the borough and is identified as a major metropolitan centre in the London Plan.[3]

Ealing was historically an ancient parish in the county of Middlesex. Until the urban expansion of London in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was a rural village.[4] Improvement in communications with London, culminating with the opening of the railway station in 1838, shifted the local economy to market garden supply and eventually to suburban development. By 1902 Ealing had become known as the "Queen of the Suburbs" due to its greenery, and because it was halfway between city and country.[5][6]

As part of the growth of London in the 20th century, Ealing significantly expanded and increased in population. It became a municipal borough in 1901 and part of Greater London in 1965. It is now a significant commercial and retail centre with a developed night-time economy. Ealing has the characteristics of both leafy suburban and inner-city development. The Pitshanger neighbourhood and some others retain the lower density, greenery and architecture of suburban villages.[7] Ealing's town centre is often referred to as Ealing Broadway, the name of both a railway interchange and a shopping centre.

Most of Ealing, including the commercial district, Ealing Broadway, South Ealing, Ealing Common, Montpelier, Pitshanger and most of Hanger Hill fall under the W5 postcode. Areas to the north-west of the town centre such as Argyle Road and West Ealing fall under W13 instead. West Twyford north-east of the town centre, near Hanger Hill, falls under the NW10 postcode area. The population of Ealing (including Northfields) was 85,014 at the 2011 census.

History

[edit]Toponymy

[edit]Ealing's name derives from the Gillingas, a Saxon tribe mentioned in a charter issued by Æthelred of Mercia around the year 700.[8] The Gillingas themselves took their name from a patriarch or chief called Gilla.[9] The place-name appears as Yllinges around the year 1170 and as Elyng in 1553.[9]

Early history

[edit]Archaeology evinces parts of Ealing have been lived in by neanderthal humans – the Lower Palaeolithic Age.[10] The typical stone tool type of neanderthals, the Mousterian, is not found in south-east England, but Levallois type may be consistent with the hand axes found.[10] These primitive hunters span a period of at least 300,000 years in Britain.[10] Of the Iron Age, Milne lists six Carthaginian and pre-Roman bronze coins from Middlesex: Ashford and Ealing (Carthage coins); Edmonton (Seleucid (2), Rhegium, Bithynia coins). These are not so significant as for similar and more plentiful finds from Dorset, and Milne suggests that some represent parts of imported bronze scrap.[11]

The Church of St. Mary's, the parish church's priest for centuries fell to be appointed by the Bishop of London, earliest known to be so in c. 1127, when he gave the great tithes to Canon Henry for keeping St. Paul's cathedral school.[12] The church required frequent repair in the 1650s and was so ruinous in about 1675 that services were held elsewhere for several years. Worshippers moved to a wooden tabernacle in 1726 and the steeple fell in 1729, destroying the church, before its rebuilding.[12] In the 12th century Ealing was amid a fields- and villages-punctuated forest covering most of the county from the southwest to the north of the City of London.

The earliest surviving English census is that for Ealing in January 1599. This list was a tally of all 85 households in Ealing village giving the names of the inhabitants, together with their ages, relationships and occupations. It survives in manuscript form at The National Archives (piece E 163/24/35), and was transcribed and printed by K J Allison for Ealing Historical Society in 1961.

Settlements were scattered throughout the parish. Many of them were along what is now called St. Mary's Road, near to the church in the centre of the parish. There were also houses at Little Ealing, Ealing Dean, Haven Green, Drayton Green and Castlebar Hill.

The parish of Ealing was far from wholly divided among manors, such as those of Ealing, Gunnersbury and Pitshanger. These when used for crops were mostly wheat, but also barley and rye, with considerable pasture for cows, draught animals, sheep and recorded poultry keeping. There were five free tenements on Ealing manor in 1423: Absdons in the north, Baldswells at Drayton, Abyndons and Denys at Ealing village, and Sergeaunts at Old Brentford. It is likely that there had once been 32 copyhold tenements, including at least 19 virgates of 20 rateable acres and 9 half virgates. When created the copyhold land amounted to not more than 540 acres (2.2 km2), a total increased before 1423 by land at Castlebar Hill.[13]

Ealing had an orchard in 1540 and others in 1577–8 and 1584.[13] Numbers increased, as were orchards often taken out of open fields, by 1616 in Crowchmans field, in 1680–1 in Popes field, and in 1738 in Little North field.[13] Some lay as far north as the centre of the parish. River Long field and adjoining closes at West Ealing contained 1,008 fruit trees in 1767, including 850 apple trees, 63 plum, and 63 cherry.[13]

Ealing demesne in 1318 had a windmill, which was rebuilt in 1363–4. This was destroyed in or before 1409 and may have been repaired by 1431, when it was again broken.[13]

Great Ealing School was founded in 1698 by the Church of St Mary's. This became the "finest private school in England" and had many famous pupils in the 19th century such as William S. Gilbert, composer and impresario, and Cardinal Newman – since 2019 recognised as a saint. As the zone became built-up, the school declined and closed in April 1908.[14] The earliest maps of just the parish of Ealing survive from the 18th century; John Speed and others having made maps of Middlesex, more than two centuries before.

At Ealing a fair was held on the green in 1822, when William Cobbett chronicled he was diverted by crowds of Cockneys headed there. The fair, of unknown origin, was held from 24 to 26 June until suppressed in 1880.[13]

The manor included Old Brentford and its extensive Thames fisheries, and in 1423 tenants of Ealing manor rented three fisheries in the Thames.[13] In 1257 the king ordered the Bishop whoever it may be from time to time (sede vacante) to provide 8,000-10,000 lampreys and other fish for owning the manor, impliedly per year, which shows the extent of the local catch.[13]

Suburb of London

[edit]With the exception of driving animals into London on foot, the transport of heavy goods tended be restricted to those times when the non-metalled roads were passable due to dry weather. With the passing of the Toll Road Act, this highway was gravelled and so the old Oxford Road became an increasingly busy and important thoroughfare running from east to west through the centre of the parish. This road was later renamed as Uxbridge Road. The well-to-do of London began to see Ealing as a place to escape from the smoke and smells. In 1800 the architect John Soane bought Payton Place and renamed it Pitzhanger Manor, not to live but just for somewhere green and pleasant, where he could entertain his friends and guests. Soon afterward, in 1801, the Duke of Kent bought a house at Castlebar. Soon, more affluent Londoners followed but with the intention of taking up a permanent residence which was conveniently close to London. The only British prime minister to be assassinated, Spencer Perceval, made his home at Elm House. Up until that point, Ealing was mostly made up of open countryside and fields where, as in previous centuries, the main occupation was farming.

Old inns and public houses

[edit]As London grew in size, more food and materials went in and more finished goods came out. Since dray horses can only haul loads a few miles per day, frequent overnight stops were needed. To satisfy this demand a large number of inns were situated along the Uxbridge Road, where horses could be changed and travellers refresh themselves, prompting its favour by highwaymen. Stops in Ealing included The Feathers, The Bell, The Green Man and The Old Hats. At one point in history there were two pubs called the Old Hat(s) either side of one of the many toll gates on the Uxbridge Road in West Ealing. Following the removal of the toll gate the more Westernmost pub was renamed The Halfway House.

Expansion

[edit]As London developed, the area became predominantly market gardens which required a greater proportion of workers as it was more labour-intensive. Ealing Grove School was established in 1834, integrating both academic and agricultural education. In the 1850s, with improved travel (the Great Western Railway and two branches of the Grand Union Canal), villages began to grow into towns and merged into unbroken residential areas. At this time Ealing began to be called the "Queen of the Suburbs".

Mount Castle Tower, an Elizabethan structure which stood at the top of Hanger Hill, was used as a tea-stop in the 19th century. It was demolished to make way for Fox's Reservoir in 1881. This reservoir, with a capacity of 3 million imperial gallons (14,000 m3), was erected north of Hill Crest Road, Hanger Hill, in 1888 and a neighbouring reservoir for 50 million imperial gallons (230,000 m3) was constructed c. 1889. This supply of good water helped to make Ealing more attractive than ever.

Mount Castle Tower was also known as Hanger Hill Tower, and as such it was a vital viewing point for the Anglo-French Survey (1784–1790), which linked the Royal Greenwich Observatory with the Paris Observatory via a chain of trigonometric readings. This survey was led in England by General William Roy. Hanger Hill Tower was its northernmost observation point, and from it sightings were made to places such as St Ann's Hill in Chertsey, Banstead, Upper Norwood, and the Greenwich Observatory itself.

Modern Victorian suburb

[edit]

The most important changes to Ealing occurred in the 19th century. The building of the Great Western Railway in the 1830s, part of which passed through the centre of Ealing, led to the opening of a railway station on the Broadway in 1879, originally called Haven Green. In the next few decades, much of Ealing was rebuilt, predominantly semi-detached housing designed for the rising middle-class. Gas mains were laid and an electricity generating station was built. Better transport links, including horse buses as well as trains, enabled people to more easily travel to work in London. All this, whilst living in what was still considered to be the countryside. Although much of the countryside was rapidly disappearing during this period of rapid expansion, parts of it were preserved as public parks, such as Lammas Park and Ealing Common. Pitzhanger Manor and the extensive 28 acres (110,000 m2) grounds on which it stands, was sold to the council in 1901 by Sir Spencer Walpole, which had been bought by his father the Rt. Hon. Spencer Horatio Walpole and thus became Walpole Park.[15]

During the Victorian period, Ealing became a town. This meant that good, well-metalled roads had to be built, and schools and public buildings erected. To protect public health, the newly created Board of Health for Ealing commissioned London's first modern drainage and sewage systems here. Just as importantly, drinking fountains providing wholesome and safe water were erected by public prescription. Ealing Broadway became a major shopping centre. The man responsible for much of all this was Charles Jones, Borough Surveyor from 1863 to 1913. He directed the planting of the horse chestnut trees on Ealing Common and designed Ealing Town Hall, both the present one and the older structure which is now a bank (on the Mall). He even oversaw the purchase of the Walpole estate grounds and its conversion into a leisure garden for the general public to enjoy and promenade around on Sundays.

Queen of the Suburbs

[edit]

In 1901, Ealing Urban District was incorporated as a municipal borough, Walpole Park was opened and the first electric trams ran along the Uxbridge Road. As part of its permit to operate, the electric tram company was required to incorporate the latest in modern street lighting into its overhead catenary supply, along the Ealing section of the Uxbridge Road. A municipally-built generating station near Clayponds Avenue supplied power to more street lighting that ran northward, up and along Mount Park Road and the surrounding streets.

It was of this area centred around Mount Park Road that Nikolaus Pevsner remarks as ”epitomising Ealing's reputation as 'Queen of the Suburbs'..”[16] In a very short time, Ealing had become a modern and fashionable country town, free of the grime, soot and smells of industrialised London, and yet only minutes away from it by modern transport.[17] The Borough Surveyor, Charles Jones, first re-used the term in the preface of his book Ealing from Village to Corporate Town of 1902, already used for Surbiton and Richmond, stressing his view that it was already recognised as of having such an identity.[18][19][20] The fairly ornate, many-roomed houses set in "sylvan beauty and floriculture" (civic trees and gardens) stood out to Jones. Mount Park Road and side roads keep much of the original character. Some neighbourhoods have resisted conversions into bed-sits, unlike many of the other original London suburbs.[21]

In the 1900s and 1910s, the Brentham Garden Suburb was built. During the interwar period several garden estates, said to be one of the best examples of classic suburbia in mock Tudor style, were built near Hanger Lane.[22] Hanger Hill Garden Village adjoining is likewise a conservation area. In the 1930s Ealing Village's mid-rise, green-setting apartment blocks were built, today Grade II (initial, mainstream) category-listed and having gated grounds.[23]

With the amalgamation of the surrounding municipal boroughs in 1965, Ealing Town Hall became the administrative centre for the new London Borough of Ealing. Today, this also includes its offices at Perceval House just next to it. Later in 1984, the Ealing Broadway Centre was completed which includes a shopping centre and a town square.

Geography

[edit]

Ealing is in the heart of west London. A relatively narrow section of the A406 North Circular Road, London bisects the east of it. The nascent M4 motorway also runs almost adjacent to the south.

It is less than two miles from the Tideway (London's upper estuary of the Thames) at the local apex of Kew Bridge that links to the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Ealing has parks and open spaces, such as Ealing Common, Walpole, Lammas, Cleveland, Hanger Hill, Montpelier, and Pitshanger Parks. The River Brent flows through the latter.

Demographics

[edit]

The largest ethnic group in the 2011 census for the Ealing Broadway ward was White British, at 45%. The second largest was Other White, at 21%. The most spoken foreign language was Polish, followed by French and Japanese.[24] The nearby Hanger Hill ward has the city's largest Japanese community.[25]

Transport

[edit]

Ealing is served by Ealing Broadway station on the Great Western Main Line and the London Underground in London fare zone 3. It is also served by five other tube stations at North Ealing, South Ealing, Hanger Lane, Northfields, Park Royal and Ealing Common. The Piccadilly line operates at Park Royal, North Ealing, Ealing Common, South Ealing and Northfields; the Central line at Ealing Broadway and Hanger Lane; and the District line at Ealing Broadway and Ealing Common. The stations at Ealing Broadway and West Ealing are served by National Rail operators Great Western Railway and TfL Rail.

Early in the 21st century Transport for London (TFL) planned to reintroduce an electric tram line along the Uxbridge Road (the West London Tram scheme), but this was abandoned in August 2007 in the face of fierce local opposition.[citation needed] Ealing Broadway and West Ealing stations became part of the Elizabeth line in 2022. A total of 18 buses (including night buses) serve Ealing Broadway.

Economy and culture

[edit]

Ealing has a developed night-time economy backed by numerous pubs and restaurants on The Mall, The Broadway and New Broadway (forming part of the greater Uxbridge Road).

Studios

[edit]

Ealing is best known for its film studios, which are the oldest in the world and are known especially for the Ealing comedies, including Kind Hearts and Coronets, Passport to Pimlico, The Ladykillers and The Lavender Hill Mob. The studios were taken over by the BBC in 1955, with one consequence being that Ealing locations appeared in television programmes including Doctor Who (notably within an iconic 1970 sequence in which deadly shop mannequins menaced local residents) to Monty Python's Flying Circus. Most recently, these studios have again been used for making films, including Notting Hill and The Importance of Being Earnest. St Trinian's, a remake of the classic film, was produced by Ealing Studios; some locations in Ealing can be seen in this film.

Most recently, Ealing Studios was the set for the famous Downton Abbey historical television series, of which the below stairs and servant's hall were filmed there. On 16 March 2015, the workplace received a visit from the Duchess of Cambridge to observe current productions, as well as meet the cast and crew of the series stated.[26]

For 14 years, Ealing lacked any cinema houses, after the closure of the Ealing Empire in 2008. 2022 saw the opening of the Ealing Project, a multi-functional community space centred around a cinema.[27]

Renovation began on the New Broadway street cinema in late 2012. Work is underway as of Spring 2021 for 'Filmworks' Archived 27 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, an Art Deco apartment-and-cinema block featuring a Picturehouse cinema. Local group Pitshanger Pictures shows classic movies in St Barnabas Millennium Hall on Pitshanger Lane.[28]

Ealing has a theatre on Mattock Lane, The Questors Theatre.

Religion

[edit]

Regarded by many as Ealing's premier architectural work, St Peter's Church, Ealing is on Mount Park Road north of central Ealing.[29] The ancient parish church of Ealing is St Mary's, in St Mary's Road. Standing near Charlbury Grove, Ealing Abbey was founded by a community of Roman Catholic Benedictine monks in 1897. Twinned with the convent of St. Augustine's Priory, the large abbey is an example of a traditional, working monastery. There are over fifteen churches in the suburb of Ealing, including Our Lady Mother of the Church, a Polish Roman Catholic church in the Mall, near Ealing Broadway.[citation needed] There are two well-established synagogues, the Ealing United Synagogue (Orthodox),[30] which celebrated its centenary in November 2019, and the Ealing Liberal Synagogue,[31] which was founded in 1943. In surrounding suburbs, there are two mosques in Acton, one in West Ealing, and two in Southall. There are large Muslim, Hindu and Sikh communities in Southall.[citation needed]

Music

[edit]

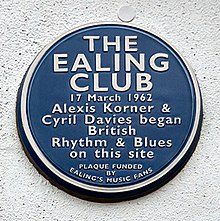

Mick Jagger and Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones famously first met Brian Jones in 1962 at the Ealing Jazz Club, opposite Ealing Broadway station. Other artists who performed at the club include Rod Stewart and Manfred Mann. The Jazz Club is now a nightclub called the Red Room.

The Beatles alighted at West Ealing station (the old building) in March 1964 to complete the filming of ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ at Edgehill Road in West Ealing.

Dusty Springfield lived in Kent Gardens, West Ealing as a teenager and attended St. Anne's Convent school in Little Ealing Lane.[32][33]

Brand New Heavies core members (drummer Jan Kincaid, guitarist Simon Bartholomew and bassist Andrew Levy) all hail from Ealing, where they formed the group in 1985.[34]

An August 2013 article in the Huffington Post claimed that Ealing could claim to be the home of rock music because of the catalyst effect of the Ealing Club on British musicians.[35]

Britney Spears filmed part of the music video for her song "Criminal" at The Corner Shop, 24 The Avenue.[citation needed]

Two members of the punk band Zatopeks grew up in Ealing, and the group frequently makes nostalgic or ironic references to the borough in its lyrics.[36][37]

Mitch Mitchell of the Jimi Hendrix Experience was born there in 1947.[38]

White Lies are also from Ealing.[39]

Sport

[edit]Ealing is home to Ealing Trailfinders Rugby Club. Due to the nearby football teams, Brentford Football Club and Queens Park Rangers, it long lacked its own. Since late 2008, Ealing Town Football Club has been registered with the Football Association and competes. Other football clubs such Old Actonians youth FC, Pitshanger youth FC[40] and Non-League football club Hanwell Town F.C. play in local leagues.

Gaelic Games have a prominent role in the Irish community in Ealing with successful clubs such as St. Joseph's GAA and Tir Chonaill GAA in neighbouring Perivale and Greenford.

Ealing has a local running club: Ealing, Southall & Middlesex AC,[41] founded in 1920. It counted double Olympic champion Kelly Holmes among its several club records to her name.[42] members.[43]

ESC D3 Triathlon Club is also based in Ealing. D3 Triathletes compete in triathlons both locally and internationally across all distances and formats including Olympic Distance and Ironman. Though an independent club it is supported by the Ealing Swimming Club based at Gurnell Leisure Centre.[44]

Cricket

[edit]Ealing Cricket Club was founded in 1870[45] and their main ground is on Corfton Road.[46] Ealing CC has a significant success record, with 11 Middlesex County Cricket League championship titles to their name.[47] Ealing field six senior teams that compete in the Middlesex County Cricket League (a designated ECB Premier League)[47] and a Woman's team in the Middlesex Cricket Women's League.[48] They also have an established junior training section that play competitive cricket in the Middlesex Junior Cricket Association.[49]

Festivals

[edit]Ealing is the host to several annual festivals. The first festival to be regularly staged was the Jazz Festival which is held in Walpole Park. An annual Beer Festival was then started and organised by the Campaign for Real Ale and originally held in the Ealing Town Hall. Due to its popularity, it had outgrown the space available at the Town Hall after a few years, so it too then transferred to the park, where they now have room to offer over 200 real ales. Each cask is supplied with individual cooling jackets to maintain the beer at exactly the right temperature. This event is run by keen volunteers. The success of these events encouraged the local council to license a broader range of festivals.

- Ealing Music and Film Valentine Festival[50]

- Ealing Beer Festival [51]

- Blues Festival[52]

- Comedy Festival[52]

- Jazz Festival[52]

- Opera in the Park[52]

In fiction

[edit]- The exterior of a suburban house in Hanger Hill was used as the house from which Reggie Perrin sets off for work in episodes of ‘The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin’ in the late 1970s.

- Ealing is the fictional setting based upon Ealing in Propershite's serial epic 'Bike Show' [53]

- Ealing was the setting for children's comedy show Rentaghost.[54]

- Ealing was the setting for part of a book in the Lockwood & Co book series.[55]

- A blue plaque commemorating the birthplace of Charles Hamilton, creator of Billy Bunter, is in the Ealing Broadway Centre.[56]

- In James Hilton's novel Goodbye, Mr Chips (1934), Katherine, the lovely young wife of the shy schoolmaster protagonist Mr Chipping, is said to have been living with an aunt in Ealing following the death of her parents.[57]

- Ealing and the surrounding area is mentioned in Aldous Huxley's Brave New World (1932). Lenina observes a Delta gymnastic display in the Ealing stadium as she flies overhead in a helicopter with Henry Foster.[58]

- In Doctor Who and related media:

- The John Sanders department store (now a branch of Marks & Spencer) was the location for the scenes of the Autons breaking through the shop window and beginning their killing rampage in the 1970 story Spearhead from Space.[59]

- On returning Ace home to the adjoining village/district of Perivale in Survival (the final serial of the 1963–1989 series), she and the Seventh Doctor ventured into Ealing and visited The Drayton Court.[59]

- In the Doctor Who spin-off series The Sarah Jane Adventures, Sarah Jane and the other regular characters lived in Ealing, and the majority of the stories were set there (although actually filmed in and around Cardiff).[59]

- Companion Clara Oswald and the Maitland family live in South Ealing.[60]

- The main character Kendra Tamale of the book Marshmallows for Breakfast by Dorothy Koomson, was said to have grown up or lived in Ealing or nearby.[61]

- George Bowling, the protagonist in Coming Up for Air by George Orwell, lived in Ealing before moving to West Bletchley.[62]

- The police station of the opening titles of Dixon of Dock Green is what was Ealing police station, at 5 High Street, just north of Ealing Green.[63][64]

- H. G. Wells' The War of the Worlds Ch. 16: "The Exodus from London". The author describing the alien deployment of poisonous, ground hugging, black vapour: "Another bank drove over Ealing, and surrounded a little island of survivors on Castle Hill, alive, but unable to escape." 'Castle Hill' was the name given in the author's time to the Victorian housing estate that sits upon Castlebar Hill and the original name of West Ealing railway station.[65]

- Thomas Merton, in his autobiography Seven Story Mountain, tells of living in Ealing for a time with his Aunt and Uncle.[66]

- Keith Stewart, the protagonist in Nevil Shute's Trustee from the Toolroom, lives in West Ealing.[67]

- Jenni Fortune, a character in Sebastian Faulks' A Week in December, lives in Drayton Green, West Ealing.[68]

Language

[edit]Ealing has been described by The Guardian as "the nation's hotspot for Polish speaking".[69]

After English, the most common languages were (in 2017) Polish (8%), Punjabi (8%), Somali (7%), Arabic (6%), Urdu (5%), and Tamil (4%). The biggest increase over the 5 years to April 2017 was Polish and tapering off – 4,363 Polish-speaking children in 2017 was 41 more than in 2016.[70]

Media

[edit]Westside 89.6FM is a community station mainly for the borough from studios based in neighbouring Hanwell. Blast Radio is the student station for the University of West London based at Ealing Studios who broadcast across the area on (RSL) in May. A digital local newspaper exists for the borough.[71]

EALING.NEWS is an independent community news website covering all of Ealing’s seven towns and soft-launched in July 2022. [72]

Politics

[edit]Ho Chi Minh worked as either a chef or dish washer (reports vary) at the Drayton Court Hotel in West Ealing.[73]

The North Korean Embassy is at 73 Gunnersbury Avenue.[74][75]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Ealing is made of six wards in the London Borough of Ealing: Cleveland, Ealing Broadway, Ealing Common, Hanger Hill, Northfield, and Walpole. "2011 Census Ward Population Estimates | London DataStore". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ Ealing Council. "Welcome to Ealing: Your Guide to Living in Ealing".

- ^ Mayor of London (February 2008). "London Plan (Consolidated with Alterations since 2004)" (PDF). Greater London Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2010.

- ^ Youngs, Frederic (1979). Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England. Vol. I: Southern England. London: Royal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-901050-67-0.

- ^ "The Queen of the Suburbs". independent.co.uk. 8 September 2000.

- ^ "Was Ealing the 'Queen of the Suburbs'? - Ealing News Extra". ealingnewsextra.co.uk. 30 October 2015. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Ealing- 'The Queen of the Suburbs'". Your Local Guardian.

- ^ Hoops, Johannes (1998). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Vol. 12 (2nd ed.). Berlin and New York: De Gruyter. p. 110. ISBN 3-11-016227-X.

- ^ a b Mills, David (2010). A Dictionary of London Place-Names (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956678-5.

- ^ a b c 'Archaeology: The Lower Palaeolithic Age', in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 1 ed. J S Cockburn, H P F King and K G T McDonnell (London, 1969), pp. 11-21. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol1/pp11-21

- ^ 'Archaeology: The Iron Age', in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 1 ed. J S Cockburn, H P F King and K G T McDonnell (London, 1969), pp. 50-64. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol1/pp50-64

- ^ a b Diane K Bolton, Patricia E C Croot and M A Hicks, Ealing and Brentford: Churches, Ealing', in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 7 ed. T F T Baker and C R Elrington (London, 1982), pp. 150-153. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol7/pp150-153

- ^ a b c d e f g h Diane K Bolton, Patricia E C Croot and M A Hicks, 'Ealing and Brentford: Economic history', in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 7, ed. T F T Baker and C R Elrington (London, 1982), pp. 131-144. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol7/pp131-144

- ^ Oates, Jonathan (May 2008). "The days when this grand school truly was 'great'" (PDF). Around Ealing. UK: Ealing Council: 27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- ^ Neaves, Cyrill (1971). A history of Greater Ealing. United Kingdom: S. R. Publishers. pp. 65, 66. ISBN 978-0-85409-679-4.

- ^ Pevsner N B L (1991). The buildings of England, London 3: North-West. ISBN 0-300-09652-6

- ^ Peter Hounsell (2005) The Ealing Book. Queen of the suburbs. Page 87. Historical Publications. ISBN 1-905286-03-1

- ^ "Was Ealing the 'Queen of the Suburbs'?". Ealing News Extra. 30 October 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ^ White, John Foster. "EALING QUEEN OF THE SUBURBS" (PDF).

- ^ Street Trees in Britain: A History, Mark Johnston and Windgather Press, Oxbow Books (Oxford, UK & Havertown, PA & Melita Press, Malta), 2017

- ^ John Foster White (1986) Ealing: Queen of the suburbs walk. Ealing Civic Society (2009 Ed). Accessed 7 November 2010

- ^ "Hanger Hill - Hidden London". hidden-london.com.

- ^ "Don't mock it". 12 November 2005. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ Services, Good Stuff IT. "Ealing Broadway - UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data.

- ^ "Demographics - Hidden London". hidden-london.com.

- ^ The Duchess of Cambridge visits the set of Downton Abbey at Ealing Studios. Accessed 7 February 2021

- ^ Ealing Project - About Us

- ^ Pitshanger Pictures Archived 24 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Details of movie screenings in St Barnabas Millennium Hall, Pitshanger Lane, W5 1QG. Accessed 29 August 2011

- ^ Cherry, B. and Pevsner, N. 'The Buildings of England London 3: North West', Yale, 2002

- ^ "EalingsSynagogue.com". Ealingsynagogue.com. Archived from the original on 18 February 2010. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- ^ "EalingLiberalsSynagogue.or.uk". Ealingliberalsynagogue.org.uk.

- ^ "Dusty Springfield - Forever Ealing!". THE EALING CLUB. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Obituary: Dusty Springfield". 4 March 1999. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ Sedazzari, Matteo (2008). "The Brand New Heavies speak to ZANI". Zani. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Sexual Ealing: Was Rock Music Born in London W5?". The Huffington Post UK. 28 August 2013.

- ^ "LETRAS - Letras de músicas e músicas para ouvir". Letras.com.br.

- ^ "Songtext: Zatopeks - Turn To Gold Blues". MusicPlayOn. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ Sweeting, Adam (14 November 2008). "Mitch Mitchell". The Guardian. United Kingdom. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ Hayes, Alex (17 December 2008). "Ealing band are critics favourite with 2009 album". Ealing Times. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Pitshanger Football Club". www.pitchero.com.

- ^ "Ealing Southall & Middlesex Athletics Club".

- ^ "UK Athletics Power of 10 Athlete Profiles – Kelly Holmes". Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ "Ealing, Southall & Middlesex Club Records". Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ "D3 Ealing Triathletes". D3 Triathlon. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ "Founded in 1833". historicengland.org.uk. Historic England. 2 August 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "About Us". ealing.play-cricket.com. Ealing CC. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Middlesex County Cricket League". middlesexccl.play-cricket.com. MCCL. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Middlesex Cricket Women's League". mwcl.play-cricket.com. MCWL. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Middlesex Junior Cricket Association". mca.play-cricket.com. MJCA. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Ealing Music and Film Valentine Festival". The Ealing Music and Film Festival Trust.

- ^ Michael Flynn. "Ealing Beer Festival 2014".

- ^ a b c d "Ealing Festivals". Ealing Council.

- ^ "Bike Show ep. 1". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Bentley, David (6 November 2014). "Remember children's TV series Rentaghost? It's 30 years since the end of Birmingham show". Birmingham Mail. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ Stroud, Jonathan (2016). Lockwood & Co: The Creeping Shadow. Random House. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-4481-9605-0.

- ^ "Billy Bunter". London Remembers. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ Hilton, James (1934). Goodbye, Mr Chips. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-553-27321-2. [page needed]

- ^ Huxley, Aldous (2008). Brave New World. Random House. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-4070-2101-0.

- ^ a b c "Dr Who and its links to the borough". Ealing News Extra. 20 October 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ Shown on the network map when she logs on in The Bells of Saint John, their home is immediately north of the intersection of S. Ealing Rd. and Pope's Ln.

- ^ Koomson, Dorothy (2017). Marshmallows for Breakfast. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1-60751-700-9. [page needed]

- ^ Orwell, George (1939). Coming Up for Air. UK: Victor Gollancz. pp. 138–141.

- ^ "Ealing and Brentford: Public services | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk.

- ^ McEwan, Kate (1983). Ealing Walkabout: Journeys into the History of a London Borough. Cheshire, UK: Nick Wheatly Associates. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-9508895-0-4.

- ^ "Ealing and Brentford: Growth of Ealing". British History Online.

- ^ Merton, Thomas (1948). The Seven Storey Mountain. Harcourt Brace. [page needed]

- ^ Shute, Nevil (1960). Trustee from the Toolroom. London: Heinemann.[page needed]

- ^ Faulks, Sebastian (2009). A Week in December. Random House. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-09-179445-3.

- ^ Booth, Robert (30 January 2013). "Polish becomes England's second language". The Guardian.

- ^ "Equalities in Ealing" (PDF). ealing.gov.uk. Ealing Council. April 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ "Ealing's Local Web site". www.ealingtoday.co.uk.

- ^ "EALING.NEWS - The Voice of our 7 Towns". www.ealing.news.

- ^ "The Drayton Court Hotel". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ^ "Foreign embassies in the UK". GOV.UK. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Inside North Korea's London embassy". The Guardian. 4 November 2014. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Bibliography

- Oates, Jonathan (31 July 2006). Foul Deeds and Suspicious Deaths in Ealing (paperback). Barnsley, South Yorkshire UK: Wharncliffe Books. ISBN 978-1-84563-012-6.

- Hounsell, Peter (1991). Ealing and Hanwell Past (Hardback). London UK: Historical Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-0-948667-13-8.

- Neaves, Cyrill (1971). A history of Greater Ealing. United Kingdom: S. R. Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85409-679-4.

- McEwan, Kate (1983) [1983]. Ealing Walkabout (Paperback). Cheshire: Pulse Publications. ISBN 978-0-9508895-0-4.

- Essen, Richard (1996). Britain in Old Photographs: Ealing & Northfields. Gloucestershire: Alan Smith Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-0-7509-1176-4.

Further reading

[edit]- James Thorne (1876), "Ealing", Handbook to the Environs of London, London: John Murray, hdl:2027/mdp.39015063815669

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Home of Ealing.com for residents

- Ealing Studios (archived 12 December 1998)

- Ealing on Facebook (Official page)