EIF4E

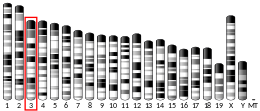

Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E, also known as eIF4E, is a protein that in humans is encoded by the EIF4E gene.[5][6]

Structure and function

[edit]Most eukaryotic cellular mRNAs are blocked at their 5'-ends with the 7-methyl-guanosine five-prime cap structure, m7GpppX (where X is any nucleotide). This structure is involved in several cellular processes including enhanced translational efficiency, splicing, mRNA stability, and RNA nuclear export. eIF4E is a eukaryotic translation initiation factor involved in directing ribosomes to the cap structure of mRNAs as well as other steps in RNA metabolism that require cap-binding. It is a 24-kD polypeptide that exists as both a free form and as part of the eIF4F pre-initiation complex.[7] Many cellular mRNAs require eIF4E in order to be translated into protein. The eIF4E polypeptide is considered by some to be the rate-limiting component of the eukaryotic translation apparatus and is involved in the mRNA-ribosome binding step of eukaryotic protein synthesis.

The other subunits of eIF4F are a 47-kD polypeptide, termed eIF4A,[8] that possesses ATPase and RNA helicase activities, and a 220-kD scaffolding polypeptide, eIF4G.[9][10][11]

Some viruses cut eIF4G in such a way that the eIF4E binding site is removed and the virus is able to translate its proteins without eIF4E. Also some cellular proteins, the most notable being heat shock proteins, do not require eIF4E in order to be translated. Both viruses and cellular proteins achieve this through an internal ribosome entry site in the RNA or through other RNA translation mechanisms such as those going through eIF3d.[12][13]

eIF4E plays roles outside of translation and other cap-binding proteins can engage in cap-dependent translation in an eIF4E-independent manner including factors such as eIF3D, eIF3I, PARN, the nuclear cap-binding complex CBC.[14][15][12][16][17][13][18] Many of these appear to be dependent on both specific features of transcripts as well as cellular context.

eIF4E is found in the nucleus of many mammalian cell types as well as in other species including yeast, drosophila and humans.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26] eIF4E is found in nuclear bodies a subset of which colocalize with PML nuclear bodies, and eIF4E is additionally found diffusely in parts of the nucleoplasm in mammalian.[23][21][24][25][27][28][26] In the nucleus, eIF4E plays well defined roles in the export of selected RNAs which contributes to its oncogenic phenotypes.[29][21][24][25][27][28][30][31][32][33] This relies on the ability of eIF4E to bind the m7G cap of RNAs and the presence of the 50 nucleotide eIF4E sensitivity element (4ESE) in the 3’UTR of sensitive transcripts; although other elements may also play a role. This form of export relies on the CRM1/XPO1 pathway.[21][24][27][34][35][26] Nuclear eIF4E has been shown to play other roles in RNA processing including in m7G capping, alternative polyadenylation and splicing.[36][37][38]

Increased nuclear accumulation of eIF4E as well as increased eIF4E-dependent RNA export, m7G capping and splicing of selected transcripts is characteristic of high-eIF4E AML patient samples.[25][30][38][37] RNAs are selected based on USER codes, or cis-acting elements, within their RNAs for specific levels of RNA processing; thus not all transcripts are sensitive to all levels of regulation (including translation).[35][39][18] For its RNA export function, eIF4E directly binds to the leucine rich pentatricopeptide repeat protein (LRPPRC) which directly binds the dorsal surface of eIF4E and simultaneously to the 4ESE RNA thereby acting as a platform for assembly for the RNA export complex.[26][35] The current model is then LRPPRC binds to CRM1/XPO1 to engage the nuclear pore and traffic the 4ESE RNA to the cytoplasm.[28][26][35] In all, the nuclear functions of eIF4E can have potent impacts on the proteome allowing eIF4E to both re-write the message as well as to increase production of proteins based on increased accumulation in the cytoplasm due to increased export as well as to increased number of ribosomes per transcript in some cases. Its multiple roles in RNA processing require its association of RNAs through the m7G cap, and thus eIF4E can be considered a cap-chaperone protein.

Regulation

[edit]Since eIF4E is an initiation factor that is relatively low in abundance, eIF4E can be controlled at multiple levels.[40][18] Regulation of eIF4E may be achieved at the levels of transcription, RNA stability phosphorylation, subcellular localization and partner proteins.[41]

a. Regulation of eIF4E by Gene Expression and RNA stability

The mechanisms responsible for eIF4E transcriptional regulation are not entirely understood. However, several reports suggest a correlation between myc levels and eIF4E mRNA levels during the cell cycle.[42] The basis of this relationship was further established by the characterization of two myc-binding sites (CACGTG E box repeats) in the promoter region of the eIF4E gene.[43] This sequence motif is shared with other in vivo targets for myc and mutations in the E box repeats of eIF4E inactivated the promoter region, thereby diminishing its expression.

Recent studies shown that eIF4E levels can be regulated at transcriptional level by NFkB and C/EBP.[44][45] Transduction of primary AML cells with IkB-SR resulted not only in reduction of eIF4E mRNA levels, but also re-localization of eIF4E protein.[25] eIF4E mRNA stability are also regulated by HuR and TIAR proteins.[46][47] eIF4E gene amplification has been observed in subset of head and neck and breast cancer specimens.[48]

b. Regulation of eIF4E by Phosphorylation

Stimuli such as hormones, growth factors, and mitogens that promote cell proliferation also enhance translation rates by phosphorylating eIF4E.[49] Although eIF4E phosphorylation and translation rates are not always correlated, consistent patterns of eIF4E phosphorylation are observed throughout the cell cycle; wherein low phosphorylation is seen during G0 and M phase and wherein high phosphorylation is seen during G1 and S phase.[50] This evidence is further supported by the crystal structure of eIF4E which suggests that phosphorylation on serine residue 209 may increase the affinity of eIF4E for capped mRNA.

eIF4E phosphorylation is also related to its ability to suppress RNA export and its oncogenic potential as first shown in cell lines.[51]

c. Regulation of eIF4E by Partner Proteins

Assembly of the eIF4F complex is inhibited by proteins known as eIF4E-binding proteins (4E-BPs), which are small heat-stable proteins that block cap-dependent translation.[41] Non-phosphorylated 4E-BPs interact strongly with eIF4E thereby preventing translation; whereas phosphorylated 4E-BPs bind weakly to eIF4E and thus do not interfere with the process of translation.[52] Furthermore, binding of the 4E-BPs inhibits phosphorylation of Ser209 on eIF4E.[53] Of note, 4E-BP1 is found in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm, indicating that it likely modulates nuclear eIF4Es functions of eIF4E as well.[54] A recent study showed that 4E-BP3 regulated eIF4E dependent mRNA nucleo-cytoplasmic export.[55] There are also many cytoplasmic regulators of eIF4E that bind to the same site as 4E-BP1.

Many other partner proteins has been found that can both stimulate or repress eIF4E activity, such as homeodomain containing proteins, including HoxA9, Hex/PRH, Hox 11, Bicoid, Emx-2 and Engrailed 2.[56][24][57][58][59] While HoxA9 promotes mRNA export and translation activities of eIF4E, Hex/PRH inhibits nuclear functions of eIF4E.[25][60][61] The RNA helicase DDX3 directly binds with eIF4E, modulates translation, and has potential functions in P-bodies and mRNA export.[62][26]

RING domains also bind eIF4E. The promyelocytic leukemia protein PML is a potent suppressor of both the nuclear RNA export and oncogenic activities of eIF4E whereby the RING domain of PML directly binds eIF4E on its dorsal surface suppressing eIF4E's oncogenic activity; and moreover a subset of PML and eIF4E nuclear bodies co-localize.[63][21][64][23][24][28] RNA-eIF4E complexes are never observed in PML bodies consistent with the observation that PML suppresses the m7G cap binding function of eIF4E.[21][64][28] Structural studies show that a related arenavirus RING finger protein, Lassa Fever Z protein, can similarly bind eIF4E on the dorsal surface.[64][65][66]

eIF4E nuclear entry is mediated by its direct interactions with Importin 8 where Importin 8 associates with the m7G cap-binding site of eIF4E.[32] Indeed, reduction in Importin 8 levels reduce the oncogenic potential of eIF4E overexpressing cells and its RNA export function. Importin 8 binds to the cap-binding site of eIF4E and is competed by excess m7G cap analogues as observed by NMR. eIF4E also stimulates the RNA export of Importin 8 RNA thereby producing more Importin 8 protein. There may be additional importins that play this role depending on cell type. Although an initial study suggested that the eIF4E transporter protein 4E-T (eIF4ENIF1) facilitated nuclear entry, later studies showed that this factor rather alters the localization of eIF4E to cytoplasmic processing bodies (P-bodies) and repress translation.[67]

Potyvirus viral protein genome linked (VPg) were found to directly bind eIF4E in its cap-binding site. VPg is covalently linked to its genomic RNA and this interaction allows VPg to act as a "cap."[68][69][16][70] The potyvirus VPg has no sequence or structural homology to other VPg's such as those from poliovirus. In vitro, VPg-RNA conjugates were translated with similar efficiency to m7G-capped RNAs indicating that VPg binds eIF4E and engages the translation machinery; while free VPg (in the absence of conjugated RNA) successfully competes for all the cap-dependent activities of eIF4E in the cell inhibiting translation and RNA export.[70]

d. Regulation of eIF4E cellular localization

Several factors that regulate eIF4E functions also modulate the subcellular localization of eIF4E. For instance, overexpression of PRH/Hex leads to cytoplasmic retention of eIF4E, and thus loss of its mRNA export activity and suppression of transformation.[24] PML overexpression leads to sequestration of eIF4E to nuclear bodies with PML and decrease of eIF4E nuclear bodies containing RNA, which correlates to repressed eIF4E dependent mRNA export and can be modulated by stress.[21][23][25] Overexpression of LRPPRC reduces eIF4E’s co-localization with PML in the nucleus and leads to increased mRNA export activity of eIF4E. As discussed above, Importin 8 brings eIF4E into the nucleus and its overexpression stimulates the RNA export and oncogenic transformation activities of eIF4E in cell lines. Transduction of primary AML cells with IkB-SR resulted not only in reduction of eIF4E mRNA levels, but also re-localization of eIF4E protein.[25]

The Role of eIF4E in Cancer

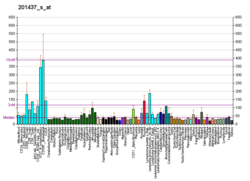

[edit]The role of eIF4E in cancer was established after Lazaris-Karatzas et al. made the discovery that over-expressing eIF4E causes tumorigenic transformation of fibroblasts.[71] Since this initial observation, numerous groups have recapitulated these results in different cell lines.[72] As a result, eIF4E activity is implicated in several cancers including cancers of the breast, lung, and prostate. In fact, transcriptional profiling of metastatic human tumors has revealed a distinct metabolic signature wherein eIF4E is known to be consistently up-regulated.[73]

eIF4E levels are increased in many cancers including acute myeloid leukemia (AML), multiple myeloma, infant ALL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, breast cancer, prostate cancer, head and neck cancer and its elevation generally correlates with poor prognosis.[30][74][75][76][77][78][79][80] In many of these cancers such as AML, eIF4E is enriched in nuclei and several of eIF4E’s activities are found to be elevated in primary patient specimens, including capping, splicing, RNA export, and translation.

In the first clinical trials targeting eIF4E, old antiviral drug ribavirin was used as a m7G cap competitor which had substantial activity in cancer cell lines and animal models associated with dysregulated eIF4E.[81][82][75][31][83][84][85][78][86][87][88][89][90][80] In the first trial to ever target eIF4E, ribavirin monotherapy was demonstrated to inhibit eIF4E activity leading to objective clinical responses including complete remissions in AML patients.[30] Interestingly, relocalization of eIF4E from the nucleus to the cytoplasm correlated with clinical remissions indicative of the relevance of its nuclear activities to disease progression.[30] Subsequent ribavirin trials in AML in combination with antileukemic drugs again showed objective clinical responses including remissions and molecular targeting of eIF4E.[76][91] Clinical responses correlated with reduced nuclear eIF4E and clinical relapse with re-emergence of eIF4E nuclear eIF4E and its RNA export activity in these AML studies. Other studies used ribavirin in combination showed similar promising results in head and neck cancer.[79] Ribavirin impairs all of the activities of eIF4E examined to date (splicing, capping, RNA export and translation). Thus, eIF4E has been successfully therapeutically targetable in humans; however drug resistance to ribavirin is an emergent problem to long term disease control.[84][76][91]

eIF4E has also been targeted by antisense oligonucleotides which were very potent in mouse models of prostate cancer,[92] but in monotherapy trials in humans did not provide clinical benefit likely due to the inefficiency of reducing eIF4E levels in humans compared to mice.[93] There is also an allosteric inhibitor of eIF4E which binds between the cap-binding site and the dorsal surface that is used experimentally.[94]

FMRP represses translation through EIF4E binding

[edit]Fragile X mental retardation protein (FMR1) acts to regulate translation of specific mRNAs through its binding of eIF4E. FMRP acts by binding CYFIP1, which directly binds eIF4e at a domain that is structurally similar to those found in 4E-BPs including EIF4EBP3, EIF4EBP1, and EIF4EBP2. The FMRP/CYFIP1 complex binds in such a way as to prevent the eIF4E-eIF4G interaction, which is necessary for translation to occur. The FMRP/CYFIP1/eIF4E interaction is strengthened by the presence of mRNA(s). In particular, BC1 RNA allows for an optimal interaction between FMRP and CYFIP1.[95] RNA-BC1 is a non-translatable, dendritic mRNA, which binds FMRP to allow for its association with a specific target mRNA. BC1 may function to regulate FMRP and mRNA interactions at synapse(s) through its recruitment of FMRP to the appropriate mRNA.[96]

In addition, FMRP may recruit CYFIP1 to specific mRNAs in order to repress translation. The FMRP-CYFIP1 translational inhibitor is regulated by stimulation of neuron(s). Increased synaptic stimulation resulted in the dissociation of eIF4E and CYFIP1, allowing for the initiation of translation.[95]

Interactions

[edit]EIF4E has been shown to interact with:

. Other direct interactors: PML;[21][64] arenavirus Z protein;[64][63][65][66] Importin 8;[32] potyvirus VPg protein,[70] LRPPRC,[35][26] RNMT[117] and others.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000151247 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000028156 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Pelletier J, Brook JD, Housman DE (August 1991). "Assignment of two of the translation initiation factor-4E (EIF4EL1 and EIF4EL2) genes to human chromosomes 4 and 20". Genomics. 10 (4): 1079–82. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(91)90203-Q. PMID 1916814.

- ^ Jones RM, MacDonald ME, Branda J, Altherr MR, Louis DN, Schmidt EV (May 1997). "Assignment of the human gene encoding eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (EIF4E) to the region q21-25 on chromosome 4". Somatic Cell and Molecular Genetics. 23 (3): 221–223. doi:10.1007/BF02721373. PMID 9330633. S2CID 10683455.

- ^ Sonenberg N, Rupprecht KM, Hecht SM, Shatkin AJ (September 1979). "Eukaryotic mRNA cap binding protein: purification by affinity chromatography on sepharose-coupled m7GDP". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 76 (9): 4345–9. Bibcode:1979PNAS...76.4345S. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.9.4345. PMC 411571. PMID 291969.

- ^ Hutchins AP, Roberts GR, Lloyd CW, Doonan JH (2004). "In vivo interaction between CDKA and eIF4A: a possible mechanism linking translation and cell proliferation". FEBS Lett. 556 (1–3): 91–4. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(03)01382-6. PMID 14706832. S2CID 35343626.

- ^ Hsieh AC, Ruggero D (11 August 2010). "Targeting Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 4E (eIF4E) in Cancer". Clinical Cancer Research. 16 (20): 4914–4920. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0433. PMC 7539621. PMID 20702611.

- ^ Rychlik W, Domier LL, Gardner PR, Hellmann GM, Rhoads RE (February 1987). "Amino acid sequence of the mRNA cap-binding protein from human tissues". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 84 (4): 945–9. Bibcode:1987PNAS...84..945R. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.4.945. PMC 304336. PMID 3469651.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: eIF4E Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E".

- ^ a b de la Parra C, Ernlund A, Alard A, Ruggles K, Ueberheide B, Schneider RJ (2018-08-03). "A widespread alternate form of cap-dependent mRNA translation initiation". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 3068. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.3068D. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05539-0. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6076257. PMID 30076308.

- ^ a b Lee AS, Kranzusch PJ, Doudna JA, Cate JH (2016-08-04). "eIF3d is an mRNA cap-binding protein that is required for specialized translation initiation". Nature. 536 (7614): 96–99. Bibcode:2016Natur.536...96L. doi:10.1038/nature18954. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5003174. PMID 27462815.

- ^ Bukhari SI, Truesdell SS, Lee S, Kollu S, Classon A, Boukhali M, Jain E, Mortensen RD, Yanagiya A, Sadreyev RI, Haas W, Vasudevan S (March 2016). "A Specialized Mechanism of Translation Mediated by FXR1a-Associated MicroRNP in Cellular Quiescence". Molecular Cell. 61 (5): 760–773. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.013. PMC 4811377. PMID 26942679.

- ^ Kumar P, Hellen CU, Pestova TV (2016-07-01). "Toward the mechanism of eIF4F-mediated ribosomal attachment to mammalian capped mRNAs". Genes & Development. 30 (13): 1573–1588. doi:10.1101/gad.282418.116. ISSN 0890-9369. PMC 4949329. PMID 27401559.

- ^ a b Borden KL, Volpon L (2020-09-01). "The diversity, plasticity, and adaptability of cap-dependent translation initiation and the associated machinery". RNA Biology. 17 (9): 1239–1251. doi:10.1080/15476286.2020.1766179. ISSN 1547-6286. PMC 7549709. PMID 32496897.

- ^ Rambout X, Maquat LE (2020-09-01). "The nuclear cap-binding complex as choreographer of gene transcription and pre-mRNA processing". Genes & Development. 34 (17–18): 1113–1127. doi:10.1101/gad.339986.120. ISSN 0890-9369. PMC 7462061. PMID 32873578.

- ^ a b c Mars JC, Ghram M, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Borden KL (2021-12-08). "The Cap-Binding Complex CBC and the Eukaryotic Translation Factor eIF4E: Co-Conspirators in Cap-Dependent RNA Maturation and Translation". Cancers. 13 (24): 6185. doi:10.3390/cancers13246185. ISSN 2072-6694. PMC 8699206. PMID 34944805.

- ^ Lejbkowicz F, Goyer C, Darveau A, Neron S, Lemieux R, Sonenberg N (1992-10-15). "A fraction of the mRNA 5' cap-binding protein, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E, localizes to the nucleus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 89 (20): 9612–9616. Bibcode:1992PNAS...89.9612L. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.20.9612. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 50182. PMID 1384058.

- ^ Dostie J, Lejbkowicz F, Sonenberg N (2000-01-24). "Nuclear Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 4e (Eif4e) Colocalizes with Splicing Factors in Speckles". Journal of Cell Biology. 148 (2): 239–246. doi:10.1083/jcb.148.2.239. ISSN 0021-9525. PMC 2174286. PMID 10648556.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cohen N (2001-08-15). "PML RING suppresses oncogenic transformation by reducing the affinity of eIF4E for mRNA". The EMBO Journal. 20 (16): 4547–4559. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.16.4547. PMC 125576. PMID 11500381.

- ^ Iborra FJ, Jackson DA, Cook PR (2001-08-10). "Coupled Transcription and Translation Within Nuclei of Mammalian Cells". Science. 293 (5532): 1139–1142. doi:10.1126/science.1061216. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 11423616. S2CID 17404294.

- ^ a b c d Topisirovic I, Capili AD, Borden KL (2002-09-01). "Gamma Interferon and Cadmium Treatments Modulate Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 4E-Dependent mRNA Transport of Cyclin D1 in a PML-Dependent Manner". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 22 (17): 6183–6198. doi:10.1128/MCB.22.17.6183-6198.2002. ISSN 1098-5549. PMC 134012. PMID 12167712.

- ^ a b c d e f g Topisirovic I (2003-02-03). "The proline-rich homeodomain protein, PRH, is a tissue-specific inhibitor of eIF4E-dependent cyclin D1 mRNA transport and growth". The EMBO Journal. 22 (3): 689–703. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdg069. PMC 140753. PMID 12554669.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Topisirovic I, Guzman ML, McConnell MJ, Licht JD, Culjkovic B, Neering SJ, Jordan CT, Borden KL (2003-12-01). "Aberrant Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 4E-Dependent mRNA Transport Impedes Hematopoietic Differentiation and Contributes to Leukemogenesis". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (24): 8992–9002. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.24.8992-9002.2003. ISSN 1098-5549. PMC 309660. PMID 14645512.

- ^ a b c d e f g Topisirovic I, Siddiqui N, Lapointe VL, Trost M, Thibault P, Bangeranye C, Piñol-Roma S, Borden KL (2009-04-22). "Molecular dissection of the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) export-competent RNP". The EMBO Journal. 28 (8): 1087–1098. doi:10.1038/emboj.2009.53. ISSN 0261-4189. PMC 2683702. PMID 19262567.

- ^ a b c Culjkovic B, Topisirovic I, Skrabanek L, Ruiz-Gutierrez M, Borden KL (2005-04-25). "eIF4E promotes nuclear export of cyclin D1 mRNAs via an element in the 3′UTR". Journal of Cell Biology. 169 (2): 245–256. doi:10.1083/jcb.200501019. ISSN 1540-8140. PMC 2171863. PMID 15837800.

- ^ a b c d e Culjkovic B, Topisirovic I, Skrabanek L, Ruiz-Gutierrez M, Borden KL (2006-11-06). "eIF4E is a central node of an RNA regulon that governs cellular proliferation". Journal of Cell Biology. 175 (3): 415–426. doi:10.1083/jcb.200607020. ISSN 1540-8140. PMC 2064519. PMID 17074885.

- ^ Rousseau D, Kaspar R, Rosenwald I, Gehrke L, Sonenberg N (1996-02-06). "Translation initiation of ornithine decarboxylase and nucleocytoplasmic transport of cyclin D1 mRNA are increased in cells overexpressing eukaryotic initiation factor 4E". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 93 (3): 1065–1070. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.1065R. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.3.1065. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 40031. PMID 8577715.

- ^ a b c d e Assouline S, Culjkovic B, Cocolakis E, Rousseau C, Beslu N, Amri A, Caplan S, Leber B, Roy DC, Miller WH, Borden KL (2009-07-09). "Molecular targeting of the oncogene eIF4E in acute myeloid leukemia (AML): a proof-of-principle clinical trial with ribavirin". Blood. 114 (2): 257–260. doi:10.1182/blood-2009-02-205153. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 19433856. S2CID 28957125.

- ^ a b Bollmann F, Fechir K, Nowag S, Koch K, Art J, Kleinert H, Pautz A (April 2013). "Human inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression depends on chromosome region maintenance 1 (CRM1)- and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (elF4E)-mediated nucleocytoplasmic mRNA transport". Nitric Oxide. 30: 49–59. doi:10.1016/j.niox.2013.02.083. PMID 23471078.

- ^ a b c Volpon L, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Osborne MJ, Ramteke A, Sun Q, Niesman A, Chook YM, Borden KL (2016-05-10). "Importin 8 mediates m 7 G cap-sensitive nuclear import of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (19): 5263–5268. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.5263V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1524291113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4868427. PMID 27114554.

- ^ Zahreddine HA, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Emond A, Pettersson F, Midura R, Lauer M, Del Rincon S, Cali V, Assouline S, Miller WH, Hascall V, Borden KL (2017-11-07). "The eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E harnesses hyaluronan production to drive its malignant activity". eLife. 6: e29830. doi:10.7554/eLife.29830. ISSN 2050-084X. PMC 5705209. PMID 29111978.

- ^ Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Fernando TM, Marullo R, Calvo-Vidal N, Verma A, Yang S, Tabbò F, Gaudiano M, Zahreddine H, Goldstein RL, Patel J, Taldone T, Chiosis G, Ladetto M, Ghione P (2016-02-18). "Combinatorial targeting of nuclear export and translation of RNA inhibits aggressive B-cell lymphomas". Blood. 127 (7): 858–868. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-05-645069. ISSN 0006-4971. PMC 4760090. PMID 26603836.

- ^ a b c d e Volpon L, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Sohn HS, Blanchet-Cohen A, Osborne MJ, Borden KL (June 2017). "A biochemical framework for eIF4E-dependent mRNA export and nuclear recycling of the export machinery". RNA. 23 (6): 927–937. doi:10.1261/rna.060137.116. ISSN 1355-8382. PMC 5435865. PMID 28325843.

- ^ Davis MR, Delaleau M, Borden KL (April 2019). "Nuclear eIF4E Stimulates 3′-End Cleavage of Target RNAs". Cell Reports. 27 (5): 1397–1408.e4. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.008. PMC 6661904. PMID 31042468.

- ^ a b Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Skrabanek L, Revuelta MV, Gasiorek J, Cowling VH, Cerchietti L, Borden KL (2020-10-27). "The eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E elevates steady-state m 7 G capping of coding and noncoding transcripts". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (43): 26773–26783. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11726773C. doi:10.1073/pnas.2002360117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7604501. PMID 33055213.

- ^ a b Ghram M, Morris G, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Mars JC, Gendron P, Skrabanek L, Revuelta MV, Cerchietti L, Guzman ML, Borden KL (2023-04-03). "The eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E reprograms alternative splicing". The EMBO Journal. 42 (7): e110496. doi:10.15252/embj.2021110496. ISSN 0261-4189. PMC 10068332. PMID 36843541.

- ^ Volpon L, Osborne MJ, Borden KL (2019-05-20). "Biochemical and Structural Insights into the Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor eIF4E". Current Protein & Peptide Science. 20 (6): 525–535. doi:10.2174/1389203720666190110142438. PMID 30636602. S2CID 58587801.

- ^ Duncan R, Milburn SC, Hershey JW (1987-01-05). "Regulated phosphorylation and low abundance of HeLa cell initiation factor eIF-4F suggest a role in translational control. Heat shock effects on eIF-4F". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 262 (1): 380–388. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)75938-9. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 3793730.

- ^ a b Richter JD, Sonenberg N (2005-02-03). "Regulation of cap-dependent translation by eIF4E inhibitory proteins". Nature. 433 (7025): 477–480. Bibcode:2005Natur.433..477R. doi:10.1038/nature03205. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 15690031. S2CID 4347657.

- ^ Rosenwald IB, Rhoads DB, Callanan LD, Isselbacher KJ, Schmidt EV (1993-07-01). "Increased expression of eukaryotic translation initiation factors eIF-4E and eIF-2 alpha in response to growth induction by c-myc". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 90 (13): 6175–6178. Bibcode:1993PNAS...90.6175R. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.13.6175. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 46890. PMID 8327497.

- ^ Jones RM, Branda J, Johnston KA, Polymenis M, Gadd M, Rustgi A, Callanan L, Schmidt EV (September 1996). "An essential E box in the promoter of the gene encoding the mRNA cap-binding protein (eukaryotic initiation factor 4E) is a target for activation by c-myc". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 16 (9): 4754–4764. doi:10.1128/mcb.16.9.4754. ISSN 0270-7306. PMC 231476. PMID 8756633.

- ^ Khanna-Gupta A, Abayasekara N, Levine M, Sun H, Virgilio M, Nia N, Halene S, Sportoletti P, Jeong JY, Pandolfi PP, Berliner N (September 2012). "Up-regulation of Translation Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 4E in Nucleophosmin 1 Haploinsufficient Cells Results in Changes in CCAAT Enhancer-binding Protein α Activity". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 287 (39): 32728–32737. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.373274. PMC 3463350. PMID 22851180.

- ^ Hariri F, Arguello M, Volpon L, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Nielsen TH, Hiscott J, Mann KK, Borden KL (October 2013). "The eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E is a direct transcriptional target of NF-κB and is aberrantly regulated in acute myeloid leukemia". Leukemia. 27 (10): 2047–2055. doi:10.1038/leu.2013.73. ISSN 0887-6924. PMC 4429918. PMID 23467026.

- ^ Mazan-Mamczarz K, Lal A, Martindale JL, Kawai T, Gorospe M (2006-04-01). "Translational Repression by RNA-Binding Protein TIAR". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 26 (7): 2716–2727. doi:10.1128/MCB.26.7.2716-2727.2006. ISSN 1098-5549. PMC 1430315. PMID 16537914.

- ^ Topisirovic I, Siddiqui N, Orolicki S, Skrabanek LA, Tremblay M, Hoang T, Borden KL (2009-03-01). "Stability of Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 4E mRNA Is Regulated by HuR, and This Activity Is Dysregulated in Cancer". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 29 (5): 1152–1162. doi:10.1128/MCB.01532-08. ISSN 1098-5549. PMC 2643828. PMID 19114552.

- ^ Sorrells DL, Black DR, Meschonat C, Rhoads R, De Benedetti A, Gao M, Williams BJ, Li BD (April 1998). "Detection of eIF4E gene amplification in breast cancer by competitive PCR". Annals of Surgical Oncology. 5 (3): 232–237. doi:10.1007/BF02303778. ISSN 1068-9265. PMID 9607624. S2CID 776478.

- ^ Morley SJ, Traugh JA (1990-06-25). "Differential stimulation of phosphorylation of initiation factors eIF-4F, eIF-4B, eIF-3, and ribosomal protein S6 by insulin and phorbol esters". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (18): 10611–10616. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)86990-3. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 2191953.

- ^ Bonneau AM, Sonenberg N (1987-08-15). "Involvement of the 24-kDa cap-binding protein in regulation of protein synthesis in mitosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 262 (23): 11134–11139. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)60935-4. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 3038908.

- ^ Topisirovic I, Ruiz-Gutierrez M, Borden KL (2004-12-01). "Phosphorylation of the Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor eIF4E Contributes to Its Transformation and mRNA Transport Activities". Cancer Research. 64 (23): 8639–8642. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2677. ISSN 0008-5472. PMID 15574771. S2CID 21104713.

- ^ Peter D, Igreja C, Weber R, Wohlbold L, Weiler C, Ebertsch L, Weichenrieder O, Izaurralde E (2015-03-19). "Molecular architecture of 4E-BP translational inhibitors bound to eIF4E". Molecular Cell. 57 (6): 1074–1087. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.017. ISSN 1097-4164. PMID 25702871.

- ^ Whalen SG, Gingras AC, Amankwa L, Mader S, Branton PE, Aebersold R, Sonenberg N (1996-05-17). "Phosphorylation of eIF-4E on serine 209 by protein kinase C is inhibited by the translational repressors, 4E-binding proteins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 271 (20): 11831–11837. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.20.11831. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 8662663.

- ^ Rong L, Livingstone M, Sukarieh R, Petroulakis E, Gingras AC, Crosby K, Smith B, Polakiewicz RD, Pelletier J, Ferraiuolo MA, Sonenberg N (July 2008). "Control of eIF4E cellular localization by eIF4E-binding proteins, 4E-BPs". RNA. 14 (7): 1318–1327. doi:10.1261/rna.950608. ISSN 1355-8382. PMC 2441981. PMID 18515545.

- ^ Chen CC, Lee JC, Chang MC (2012-07-30). "4E-BP3 regulates eIF4E-mediated nuclear mRNA export and interacts with replication protein A2". FEBS Letters. 586 (16): 2260–2266. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.059. PMID 22684010. S2CID 40980342.

- ^ Niessing D, Blanke S, Jäckle H (2002-10-01). "Bicoid associates with the 5′-cap-bound complex of caudal mRNA and represses translation". Genes & Development. 16 (19): 2576–2582. doi:10.1101/gad.240002. ISSN 0890-9369. PMC 187448. PMID 12368268.

- ^ Nédélec S, Foucher I, Brunet I, Bouillot C, Prochiantz A, Trembleau A (2004-07-20). "Emx2 homeodomain transcription factor interacts with eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) in the axons of olfactory sensory neurons". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (29): 10815–10820. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10110815N. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403824101. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 490017. PMID 15247416.

- ^ Brunet I, Weinl C, Piper M, Trembleau A, Volovitch M, Harris W, Prochiantz A, Holt C (November 2005). "The transcription factor Engrailed-2 guides retinal axons". Nature. 438 (7064): 94–98. Bibcode:2005Natur.438...94B. doi:10.1038/nature04110. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 3785142. PMID 16267555.

- ^ Topisirovic I, Borden KL (October 2005). "Homeodomain proteins and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E): an unexpected relationship". Histology and Histopathology. 20 (20): 1275–1284. doi:10.14670/HH-20.1275. ISSN 0213-3911. PMID 16136508.

- ^ Kuroda N, Guo L, Miyazaki E, Hamauzu T, Toi M, Hiroi M, Enzan H (2005-01-01). "The appearance of myofibroblasts and the disappearance of CD34-positive stromal cells in the area adjacent to xanthogranulomatous foci of chronic cholecystitis". Histology and Histopathology. 20 (20): 127–133. doi:10.14670/HH-20.127. ISSN 0213-3911. PMID 15578431.

- ^ Topisirovic I, Kentsis A, Perez JM, Guzman ML, Jordan CT, Borden KL (2005-02-01). "Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 4E Activity Is Modulated by HOXA9 at Multiple Levels". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 25 (3): 1100–1112. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.3.1100-1112.2005. ISSN 1098-5549. PMC 544005. PMID 15657436.

- ^ Shih JW, Tsai TY, Chao CH, Wu Lee YH (2008-01-24). "Candidate tumor suppressor DDX3 RNA helicase specifically represses cap-dependent translation by acting as an eIF4E inhibitory protein". Oncogene. 27 (5): 700–714. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1210687. ISSN 0950-9232. PMID 17667941. S2CID 19781838.

- ^ a b Kentsis A, Gordon RE, Borden KL (2002-11-26). "Control of biochemical reactions through supramolecular RING domain self-assembly". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (24): 15404–15409. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9915404K. doi:10.1073/pnas.202608799. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 137729. PMID 12438698.

- ^ a b c d e Kentsis A, Dwyer EC, Perez JM, Sharma M, Chen A, Pan ZQ, Borden KL (September 2001). "The RING domains of the promyelocytic leukemia protein PML and the arenaviral protein Z repress translation by directly inhibiting translation initiation factor eIF4E 1 1Edited by D. Draper". Journal of Molecular Biology. 312 (4): 609–623. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2001.5003. PMID 11575918.

- ^ a b Kentsis A, Gordon RE, Borden KL (2002-01-22). "Self-assembly properties of a model RING domain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (2): 667–672. doi:10.1073/pnas.012317299. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 117363. PMID 11792829.

- ^ a b Volpon L, Osborne MJ, Capul AA, de la Torre JC, Borden KL (2010-03-23). "Structural characterization of the Z RING-eIF4E complex reveals a distinct mode of control for eIF4E". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (12): 5441–5446. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.5441V. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909877107. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2851782. PMID 20212144.

- ^ Ferraiuolo MA, Basak S, Dostie J, Murray EL, Schoenberg DR, Sonenberg N (2005-09-12). "A role for the eIF4E-binding protein 4E-T in P-body formation and mRNA decay". Journal of Cell Biology. 170 (6): 913–924. doi:10.1083/jcb.200504039. ISSN 1540-8140. PMC 2171455. PMID 16157702.

- ^ German-Retana S, Walter J, Le Gall O (March 2008). "Lettuce mosaic virus: from pathogen diversity to host interactors". Molecular Plant Pathology. 9 (2): 127–136. doi:10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00451.x. ISSN 1464-6722. PMC 6640324. PMID 18705846.

- ^ Coutinho de Oliveira L, Volpon L, Osborne MJ, Borden KL (April 2019). "Chemical shift assignment of the viral protein genome-linked (VPg) from potato virus Y". Biomolecular NMR Assignments. 13 (1): 9–13. doi:10.1007/s12104-018-9842-3. ISSN 1874-2718. PMC 6428624. PMID 30242622.

- ^ a b c Coutinho de Oliveira L, Volpon L, Rahardjo AK, Osborne MJ, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Trahan C, Oeffinger M, Kwok BH, Borden KL (2019-11-26). "Structural studies of the eIF4E–VPg complex reveal a direct competition for capped RNA: Implications for translation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (48): 24056–24065. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11624056C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1904752116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6883836. PMID 31712417.

- ^ Lazaris-Karatzas A, Montine KS, Sonenberg N (1990-06-07). "Malignant transformation by a eukaryotic initiation factor subunit that binds to mRNA 5' cap". Nature. 345 (6275): 544–547. Bibcode:1990Natur.345..544L. doi:10.1038/345544a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 2348862. S2CID 4366949.

- ^ Pelletier J, Graff J, Ruggero D, Sonenberg N (2015-01-15). "TARGETING THE eIF4F TRANSLATION INITIATION COMPLEX: A CRITICAL NEXUS FOR CANCER DEVELOPMENT". Cancer Research. 75 (2): 250–263. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2789. ISSN 0008-5472. PMC 4299928. PMID 25593033.

- ^ Ramaswamy S, Ross KN, Lander ES, Golub TR (January 2003). "A molecular signature of metastasis in primary solid tumors". Nature Genetics. 33 (1): 49–54. doi:10.1038/ng1060. ISSN 1546-1718. PMID 12469122. S2CID 12059602.

- ^ Culjkovic B, Borden KL (2009). "Understanding and Targeting the Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor eIF4E in Head and Neck Cancer". Journal of Oncology. 2009: 981679. doi:10.1155/2009/981679. ISSN 1687-8450. PMC 2798714. PMID 20049173.

- ^ a b Pettersson F, Yau C, Dobocan MC, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Retrouvay H, Puckett R, Flores LM, Krop IE, Rousseau C, Cocolakis E, Borden KL, Benz CC, Miller WH (2011-05-01). "Ribavirin Treatment Effects on Breast Cancers Overexpressing eIF4E, a Biomarker with Prognostic Specificity for Luminal B-Type Breast Cancer". Clinical Cancer Research. 17 (9): 2874–2884. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2334. ISSN 1078-0432. PMC 3086959. PMID 21415224.

- ^ a b c Assouline S, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Bergeron J, Caplan S, Cocolakis E, Lambert C, Lau CJ, Zahreddine HA, Miller WH, Borden KL (2015-01-01). "A phase I trial of ribavirin and low-dose cytarabine for the treatment of relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia with elevated eIF4E". Haematologica. 100 (1): e7–e9. doi:10.3324/haematol.2014.111245. ISSN 0390-6078. PMC 4281321. PMID 25425688.

- ^ Attar-Schneider O, Pasmanik-Chor M, Tartakover-Matalon S, Drucker L, Lishner M (2015-02-28). "eIF4E and eIF4GI have distinct and differential imprints on multiple myeloma's proteome and signaling". Oncotarget. 6 (6): 4315–4329. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.3008. ISSN 1949-2553. PMC 4414192. PMID 25717031.

- ^ a b Zismanov V, Attar-Schneider O, Lishner M, Aizenfeld RH, Matalon ST, Drucker L (February 2015). "Multiple myeloma proteostasis can be targeted via translation initiation factor eIF4E". International Journal of Oncology. 46 (2): 860–870. doi:10.3892/ijo.2014.2774. ISSN 1019-6439. PMID 25422161.

- ^ a b Dunn LA, Fury MG, Sherman EJ, Ho AA, Katabi N, Haque SS, Pfister DG (February 2018). "Phase I study of induction chemotherapy with afatinib, ribavirin, and weekly carboplatin and paclitaxel for stage IVA/IVB human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer". Head & Neck. 40 (2): 233–241. doi:10.1002/hed.24938. PMC 6760238. PMID 28963790.

- ^ a b Urtishak KA, Wang LS, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Davenport JW, Porazzi P, Vincent TL, Teachey DT, Tasian SK, Moore JS, Seif AE, Jin S, Barrett JS, Robinson BW, Chen IM, Harvey RC (2019-03-28). "Targeting EIF4E signaling with ribavirin in infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Oncogene. 38 (13): 2241–2262. doi:10.1038/s41388-018-0567-7. ISSN 0950-9232. PMC 6440839. PMID 30478448.

- ^ Kentsis A, Topisirovic I, Culjkovic B, Shao L, Borden KL (2004-12-28). "Ribavirin suppresses eIF4E-mediated oncogenic transformation by physical mimicry of the 7-methyl guanosine mRNA cap". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (52): 18105–18110. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10118105K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0406927102. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 539790. PMID 15601771.

- ^ Kentsis A, Volpon L, Topisirovic I, Soll CE, Culjkovic B, Shao L, Borden KL (December 2005). "Further evidence that ribavirin interacts with eIF4E". RNA. 11 (12): 1762–1766. doi:10.1261/rna.2238705. ISSN 1355-8382. PMC 1370864. PMID 16251386.

- ^ Volpon L, Osborne MJ, Zahreddine H, Romeo AA, Borden KL (May 2013). "Conformational changes induced in the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E by a clinically relevant inhibitor, ribavirin triphosphate". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 434 (3): 614–619. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.125. PMC 3659399. PMID 23583375.

- ^ a b Zahreddine HA, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Assouline S, Gendron P, Romeo AA, Morris SJ, Cormack G, Jaquith JB, Cerchietti L, Cocolakis E, Amri A, Bergeron J, Leber B, Becker MW, Pei S (2014-07-03). "The sonic hedgehog factor GLI1 imparts drug resistance through inducible glucuronidation". Nature. 511 (7507): 90–93. Bibcode:2014Natur.511...90Z. doi:10.1038/nature13283. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 4138053. PMID 24870236.

- ^ Shi F, Len Y, Gong Y, Shi R, Yang X, Naren D, Yan T (2015-08-28). Eaves CJ (ed.). "Ribavirin Inhibits the Activity of mTOR/eIF4E, ERK/Mnk1/eIF4E Signaling Pathway and Synergizes with Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Imatinib to Impair Bcr-Abl Mediated Proliferation and Apoptosis in Ph+ Leukemia". PLOS ONE. 10 (8): e0136746. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1036746S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136746. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4552648. PMID 26317515.

- ^ Dai D, Chen H, Tang J, Tang Y (January 2017). "Inhibition of mTOR/eIF4E by anti-viral drug ribavirin effectively enhances the effects of paclitaxel in oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 482 (4): 1259–1264. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.12.025. PMID 27932243.

- ^ Volpin F, Casaos J, Sesen J, Mangraviti A, Choi J, Gorelick N, Frikeche J, Lott T, Felder R, Scotland SJ, Eisinger-Mathason TS, Brem H, Tyler B, Skuli N (2017-05-25). "Use of an anti-viral drug, Ribavirin, as an anti-glioblastoma therapeutic". Oncogene. 36 (21): 3037–3047. doi:10.1038/onc.2016.457. ISSN 0950-9232. PMID 27941882. S2CID 21655102.

- ^ Wang G, Li Z, Li Z, Huang Y, Mao X, Xu C, Cui S (December 2017). "Targeting eIF4E inhibits growth, survival and angiogenesis in retinoblastoma and enhances efficacy of chemotherapy". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 96: 750–756. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2017.10.034. PMID 29049978.

- ^ Xi C, Wang L, Yu J, Ye H, Cao L, Gong Z (September 2018). "Inhibition of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E is effective against chemo-resistance in colon and cervical cancer". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 503 (4): 2286–2292. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.06.150. PMID 29959920. S2CID 49634908.

- ^ Jin J, Xiang W, Wu S, Wang M, Xiao M, Deng A (March 2019). "Targeting eIF4E signaling with ribavirin as a sensitizing strategy for ovarian cancer". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 510 (4): 580–586. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.01.117. PMID 30739792. S2CID 73419809.

- ^ a b Assouline S, Gasiorek J, Bergeron J, Lambert C, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Cocolakis E, Zakaria C, Szlachtycz D, Yee K, Borden KL (2023-03-23). "Molecular targeting of the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes in high-eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E refractory/relapsed acute myeloid leukemia patients: a randomized phase II trial of vismodegib, ribavirin with or without decitabine". Haematologica. 108 (11): 2946–2958. doi:10.3324/haematol.2023.282791. ISSN 1592-8721. PMC 10620574. PMID 36951168. S2CID 257733013.

- ^ Graff JR, Konicek BW, Vincent TM, Lynch RL, Monteith D, Weir SN, Schwier P, Capen A, Goode RL, Dowless MS, Chen Y, Zhang H, Sissons S, Cox K, McNulty AM (2007-09-04). "Therapeutic suppression of translation initiation factor eIF4E expression reduces tumor growth without toxicity". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 117 (9): 2638–2648. doi:10.1172/JCI32044. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 1957541. PMID 17786246.

- ^ Hong DS, Kurzrock R, Oh Y, Wheler J, Naing A, Brail L, Callies S, André V, Kadam SK, Nasir A, Holzer TR, Meric-Bernstam F, Fishman M, Simon G (2011-10-15). "A Phase 1 Dose Escalation, Pharmacokinetic, and Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of eIF-4E Antisense Oligonucleotide LY2275796 in Patients with Advanced Cancer". Clinical Cancer Research. 17 (20): 6582–6591. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0430. ISSN 1078-0432. PMC 5036398. PMID 21831956.

- ^ Papadopoulos E, Jenni S, Kabha E, Takrouri KJ, Yi T, Salvi N, Luna RE, Gavathiotis E, Mahalingam P, Arthanari H, Rodriguez-Mias R, Yefidoff-Freedman R, Aktas BH, Chorev M, Halperin JA (2014-08-05). "Structure of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E in complex with 4EGI-1 reveals an allosteric mechanism for dissociating eIF4G". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (31): E3187-95. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111E3187P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1410250111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4128100. PMID 25049413.

- ^ a b Napoli I, Mercaldo V, Boyl PP, Eleuteri B, Zalfa F, De Rubeis S, Di Marino D, Mohr E, Massimi M, Falconi M, Witke W, Costa-Mattioli M, Sonenberg N, Achsel T, Bagni C (September 2008). "The Fragile X Syndrome Protein Represses Activity-Dependent Translation through CYFIP1, a New 4E-BP". Cell. 134 (6): 1042–1054. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.031. PMID 18805096. S2CID 14123165.

- ^ Zalfa F, Giorgi M, Primerano B, Moro A, Di Penta A, Reis S, Oostra B, Bagni C (February 2003). "The fragile X syndrome protein FMRP associates with BC1 RNA and regulates the translation of specific mRNAs at synapses". Cell. 112 (3): 317–27. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00079-5. PMID 12581522. S2CID 14892764.

- ^ a b Ewing RM, Chu P, Elisma F, Li H, Taylor P, Climie S, McBroom-Cerajewski L, Robinson MD, O'Connor L, Li M, Taylor R, Dharsee M, Ho Y, Heilbut A, Moore L, Zhang S, Ornatsky O, Bukhman YV, Ethier M, Sheng Y, Vasilescu J, Abu-Farha M, Lambert JP, Duewel HS, Stewart II, Kuehl B, Hogue K, Colwill K, Gladwish K, Muskat B, Kinach R, Adams SL, Moran MF, Morin GB, Topaloglou T, Figeys D (2007). "Large-scale mapping of human protein-protein interactions by mass spectrometry". Mol. Syst. Biol. 3: 89. doi:10.1038/msb4100134. PMC 1847948. PMID 17353931.

- ^ a b c Connolly E, Braunstein S, Formenti S, Schneider RJ (May 2006). "Hypoxia inhibits protein synthesis through a 4E-BP1 and elongation factor 2 kinase pathway controlled by mTOR and uncoupled in breast cancer cells". Mol. Cell. Biol. 26 (10): 3955–65. doi:10.1128/MCB.26.10.3955-3965.2006. PMC 1489005. PMID 16648488.

- ^ Rual JF, Venkatesan K, Hao T, Hirozane-Kishikawa T, Dricot A, Li N, Berriz GF, Gibbons FD, Dreze M, Ayivi-Guedehoussou N, Klitgord N, Simon C, Boxem M, Milstein S, Rosenberg J, Goldberg DS, Zhang LV, Wong SL, Franklin G, Li S, Albala JS, Lim J, Fraughton C, Llamosas E, Cevik S, Bex C, Lamesch P, Sikorski RS, Vandenhaute J, Zoghbi HY, Smolyar A, Bosak S, Sequerra R, Doucette-Stamm L, Cusick ME, Hill DE, Roth FP, Vidal M (October 2005). "Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein-protein interaction network". Nature. 437 (7062): 1173–8. Bibcode:2005Natur.437.1173R. doi:10.1038/nature04209. PMID 16189514. S2CID 4427026.

- ^ a b c Mader S, Lee H, Pause A, Sonenberg N (September 1995). "The translation initiation factor eIF-4E binds to a common motif shared by the translation factor eIF-4 gamma and the translational repressors 4E-binding proteins". Mol. Cell. Biol. 15 (9): 4990–7. doi:10.1128/MCB.15.9.4990. PMC 230746. PMID 7651417.

- ^ Rao RD, Mladek AC, Lamont JD, Goble JM, Erlichman C, James CD, Sarkaria JN (October 2005). "Disruption of parallel and converging signaling pathways contributes to the synergistic antitumor effects of simultaneous mTOR and EGFR inhibition in GBM cells". Neoplasia. 7 (10): 921–9. doi:10.1593/neo.05361. PMC 1502028. PMID 16242075.

- ^ Eguchi S, Tokunaga C, Hidayat S, Oshiro N, Yoshino K, Kikkawa U, Yonezawa K (July 2006). "Different roles for the TOS and RAIP motifs of the translational regulator protein 4E-BP1 in the association with raptor and phosphorylation by mTOR in the regulation of cell size". Genes Cells. 11 (7): 757–66. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00977.x. PMID 16824195. S2CID 30113895.

- ^ Yang D, Brunn GJ, Lawrence JC (June 1999). "Mutational analysis of sites in the translational regulator, PHAS-I, that are selectively phosphorylated by mTOR". FEBS Lett. 453 (3): 387–90. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00762-0. PMID 10405182. S2CID 5023204.

- ^ Patel J, McLeod LE, Vries RG, Flynn A, Wang X, Proud CG (June 2002). "Cellular stresses profoundly inhibit protein synthesis and modulate the states of phosphorylation of multiple translation factors". Eur. J. Biochem. 269 (12): 3076–85. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02992.x. PMID 12071973.

- ^ a b Kumar V, Sabatini D, Pandey P, Gingras AC, Majumder PK, Kumar M, Yuan ZM, Carmichael G, Weichselbaum R, Sonenberg N, Kufe D, Kharbanda S (April 2000). "Regulation of the rapamycin and FKBP-target 1/mammalian target of rapamycin and cap-dependent initiation of translation by the c-Abl protein-tyrosine kinase". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (15): 10779–87. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.15.10779. PMID 10753870.

- ^ Kumar V, Pandey P, Sabatini D, Kumar M, Majumder PK, Bharti A, Carmichael G, Kufe D, Kharbanda S (March 2000). "Functional interaction between RAFT1/FRAP/mTOR and protein kinase cdelta in the regulation of cap-dependent initiation of translation". EMBO J. 19 (5): 1087–97. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.5.1087. PMC 305647. PMID 10698949.

- ^ Gingras AC, Gygi SP, Raught B, Polakiewicz RD, Abraham RT, Hoekstra MF, Aebersold R, Sonenberg N (June 1999). "Regulation of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation: a novel two-step mechanism". Genes Dev. 13 (11): 1422–37. doi:10.1101/gad.13.11.1422. PMC 316780. PMID 10364159.

- ^ Shen X, Tomoo K, Uchiyama S, Kobayashi Y, Ishida T (October 2001). "Structural and thermodynamic behavior of eukaryotic initiation factor 4E in supramolecular formation with 4E-binding protein 1 and mRNA cap analogue, studied by spectroscopic methods". Chem. Pharm. Bull. 49 (10): 1299–303. doi:10.1248/cpb.49.1299. PMID 11605658.

- ^ Adegoke OA, Chevalier S, Morais JA, Gougeon R, Kimball SR, Jefferson LS, Wing SS, Marliss EB (January 2009). "Fed-state clamp stimulates cellular mechanisms of muscle protein anabolism and modulates glucose disposal in normal men". Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 296 (1): E105–13. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.90752.2008. PMC 2636991. PMID 18957614.

- ^ Pause A, Belsham GJ, Gingras AC, Donzé O, Lin TA, Lawrence JC, Sonenberg N (October 1994). "Insulin-dependent stimulation of protein synthesis by phosphorylation of a regulator of 5'-cap function". Nature. 371 (6500): 762–7. Bibcode:1994Natur.371..762P. doi:10.1038/371762a0. PMID 7935836. S2CID 4360955.

- ^ Kleijn M, Scheper GC, Wilson ML, Tee AR, Proud CG (December 2002). "Localisation and regulation of the eIF4E-binding protein 4E-BP3". FEBS Lett. 532 (3): 319–23. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03694-3. PMID 12482586. S2CID 24527449.

- ^ Poulin F, Gingras AC, Olsen H, Chevalier S, Sonenberg N (May 1998). "4E-BP3, a new member of the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein family". J. Biol. Chem. 273 (22): 14002–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.22.14002. PMID 9593750.

- ^ Dostie J, Ferraiuolo M, Pause A, Adam SA, Sonenberg N (June 2000). "A novel shuttling protein, 4E-T, mediates the nuclear import of the mRNA 5' cap-binding protein, eIF4E". EMBO J. 19 (12): 3142–56. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.12.3142. PMC 203362. PMID 10856257.

- ^ Vary TC, Jefferson LS, Kimball SR (December 1999). "Amino acid-induced stimulation of translation initiation in rat skeletal muscle". Am. J. Physiol. 277 (6 Pt 1): E1077–86. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.6.E1077. PMID 10600798. S2CID 4516850.

- ^ Harris TE, Chi A, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Rhoads RE, Lawrence JC (April 2006). "mTOR-dependent stimulation of the association of eIF4G and eIF3 by insulin". EMBO J. 25 (8): 1659–68. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601047. PMC 1440840. PMID 16541103.

- ^ Gradi A, Imataka H, Svitkin YV, Rom E, Raught B, Morino S, Sonenberg N (January 1998). "A novel functional human eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G". Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 (1): 334–42. doi:10.1128/mcb.18.1.334. PMC 121501. PMID 9418880.

- ^ Osborne MJ, Volpon L, Memarpoor-Yazdi M, Pillay S, Thambipillai A, Czarnota S, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B, Trahan C, Oeffinger M, Cowling VH, Borden KL (March 2022). "Identification and Characterization of the Interaction Between the Methyl-7-Guanosine Cap Maturation Enzyme RNMT and the Cap-Binding Protein eIF4E". Journal of Molecular Biology. 434 (5): 167451. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2022.167451. PMC 9288840. PMID 35026230.

Further reading

[edit]- Jain S, Khuri FR, Shin DM (2004). "Prevention of head and neck cancer: current status and future prospects". Current Problems in Cancer. 28 (5): 265–86. doi:10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2004.05.003. PMID 15375804.

- Culjkovic B, Topisirovic I, Borden KL (2007). "Controlling gene expression through RNA regulons: the role of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E". Cell Cycle. 6 (1): 65–9. doi:10.4161/cc.6.1.3688. PMID 17245113.

- Malys N, McCarthy JE (2010). "Translation initiation: variations in the mechanism can be anticipated". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 68 (6): 991–1003. doi:10.1007/s00018-010-0588-z. PMC 11115079. PMID 21076851. S2CID 31720000.

External links

[edit]- Cap-dependent translation initiation from Nature Reviews Microbiology. A good image and overview of the function of initiation factors.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.