Lutein

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

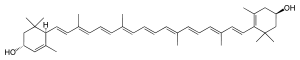

| IUPAC name

(3R,6R,3′R)-β,ε-Carotene-3,3′-diol

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(1R,4R)-4-{(1E,3E,5E,7E,9E,11E,13E,15E,17E)-18-[(4R)-4-Hydroxy-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-en-1-yl]-3,7,12,16-tetramethyloctadeca-1,3,5,7,9,11,13,15,17-nonaen-1-yl}-3,5,5-trimethylcyclohex-2-en-1-ol | |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.401 |

| E number | E161b (colours) |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C40H56O2 | |

| Molar mass | 568.871 g/mol |

| Appearance | Red-orange crystalline solid |

| Melting point | 190 °C (374 °F; 463 K)[1] |

| Insoluble | |

| Solubility in fats | Soluble |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Lutein (/ˈljuːtiɪn, -tiːn/;[2] from Latin luteus meaning "yellow") is a xanthophyll and one of 600 known naturally occurring carotenoids. Lutein is synthesized only by plants, and like other xanthophylls is found in high quantities in green leafy vegetables such as spinach, kale and yellow carrots. In green plants, xanthophylls act to modulate light energy and serve as non-photochemical quenching agents to deal with triplet chlorophyll, an excited form of chlorophyll which is overproduced at very high light levels during photosynthesis. See xanthophyll cycle for this topic.

Animals obtain lutein by ingesting plants.[3] In the human retina, lutein is absorbed from blood specifically into the macula lutea,[4] although its precise role in the body is unknown.[3] Lutein is also found in egg yolks and animal fats.

Lutein is isomeric with zeaxanthin, differing only in the placement of one double bond. Lutein and zeaxanthin can be interconverted in the body through an intermediate called meso-zeaxanthin.[5] The principal natural stereoisomer of lutein is (3R,3′R,6′R)-beta,epsilon-carotene-3,3′-diol. Lutein is a lipophilic molecule and is generally insoluble in water. The presence of the long chromophore of conjugated double bonds (polyene chain) provides the distinctive light-absorbing properties. The polyene chain is susceptible to oxidative degradation by light or heat and is chemically unstable in acids.

Lutein is present in plants as fatty-acid esters, with one or two fatty acids bound to the two hydroxyl-groups. For this reason, saponification (de-esterification) of lutein esters to yield free lutein may yield lutein in any ratio from 1:1 to 1:2 molar ratio with the saponifying fatty acid.

As a pigment

[edit]This xanthophyll, like its sister compound zeaxanthin, has primarily been used in food and supplement manufacturing as a colorant due to its yellow-red color.[3][6] Lutein absorbs blue light and therefore appears yellow at low concentrations and orange-red at high concentrations.

Many songbirds (like golden oriole, evening grosbeak, yellow warbler, common yellowthroat and Javan green magpies, but not American goldfinch or yellow canaries[7]) deposit lutein obtained from the diet into growing tissues to color their feathers.[8][9]

Role in human eyes

[edit]Although lutein is concentrated in the macula – a small area of the retina responsible for three-color vision – the precise functional role of retinal lutein has not been determined.[3]

Macular degeneration

[edit]In 2013, findings of the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS2) showed that a dietary supplement formulation containing lutein reduced progression of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) by 25 percent.[10][11] However, lutein and zeaxanthin had no overall effect on preventing AMD, but rather "the participants with low dietary intake of lutein and zeaxanthin at the start of the study, but who took an AREDS formulation with lutein and zeaxanthin during the study, were about 25 percent less likely to develop advanced AMD compared with participants with similar dietary intake who did not take lutein and zeaxanthin."[11]

In AREDS2, participants took one of four AREDS formulations: the original AREDS formulation, AREDS formulation with no beta-carotene, AREDS with low zinc, AREDS with no beta-carotene and low zinc. In addition, they took one of four additional supplement or combinations including lutein and zeaxanthin (10 mg and 2 mg), omega-3 fatty acids (1,000 mg), lutein/zeaxanthin and omega-3 fatty acids, or placebo. The study reported that there was no overall additional benefit from adding omega-3 fatty acids or lutein and zeaxanthin to the formulation. However, the study did find benefits in two subgroups of participants: those not given beta-carotene, and those who had little lutein and zeaxanthin in their diets. Removing beta-carotene did not curb the formulation's protective effect against developing advanced AMD, which was important given that high doses of beta-carotene had been linked to higher risk of lung cancers in smokers. It was recommended to replace beta-carotene with lutein and zeaxanthin in future formulations for these reasons.[10]

- Three subsequent meta-analyses of dietary lutein and zeaxanthin concluded that these carotenoids lower the risk of progression from early stage AMD to late stage AMD.[12][13][14]

- An updated 2023 Cochrane review of 26 studies from several countries, however, concluded that dietary supplements containing zeaxanthin and lutein alone have little effect when compared to placebo on the progression of AMD.[15] In general, there remains insufficient evidence to assess the effectiveness of dietary or supplemental zeaxanthin or lutein in treatment or prevention of early AMD.[16][15]

Cataract research

[edit]There is preliminary epidemiological evidence that increasing lutein and zeaxanthin intake lowers the risk of cataract development.[3][17][18] Consumption of more than 2.4 mg of lutein/zeaxanthin daily from foods and supplements was significantly correlated with reduced incidence of nuclear lens opacities, as revealed from data collected during a 13- to 15-year period in one study.[19]

Two meta-analyses confirm a correlation between high diet content or high serum concentrations of lutein and zeaxanthin and a decrease in the risk of cataract.[20][21] There is only one published clinical intervention trial testing for an effect of lutein and zeaxanthin supplementation on cataracts. The AREDS2 trial enrolled subjects at risk for progression to advanced age-related macular degeneration. Overall, the group getting lutein (10 mg) and zeaxanthin (2 mg) were NOT less likely to progress to needing cataract surgery. The authors speculated that there may be a cataract prevention benefit for people with low dietary intake of lutein and zeaxanthin, but recommended more research.[22]

In diet

[edit]Lutein is a natural part of a human diet found in orange-yellow fruits and flowers, and in leafy vegetables. According to the NHANES 2013-2014 survey, adults in the United States consume on average 1.7 mg/day of lutein and zeaxanthin combined.[23] No recommended dietary allowance currently exists for lutein. Some positive health effects have been seen at dietary intake levels of 6–10 mg/day.[24] The only definitive side effect of excess lutein consumption is bronzing of the skin (carotenodermia).[citation needed]

As a food additive, lutein has the E number E161b (INS number 161b) and is extracted from the petals of African marigold (Tagetes erecta).[25] It is approved for use in the EU[26] and Australia and New Zealand.[27] In the United States lutein may not be used as a food coloring for foods intended for human consumption, but can be added to animal feed and is allowed as a human dietary supplement often in combination with zeaxanthin. Example: lutein fed to chickens will show up in skin color and egg yolk color.[28][29]

Some foods contain relatively high amounts of lutein:[3][17][30][31][32][33]

| Product | Lutein + zeaxanthin[3] (micrograms per 100 grams) |

|---|---|

| nasturtium (yellow flowers, lutein levels only) | 45,000[31] |

| pot marigold (yellow and orange flowers, lutein levels only) | 29,800 |

| kale (raw) | 39,550 |

| kale (cooked) | 18,246 |

| dandelion leaves (raw) | 13,610 |

| nasturtium (leaves, lutein levels only) | 13,600[31] |

| turnip greens (raw) | 12,825 |

| spinach (raw) | 12,198 |

| spinach (cooked) | 11,308 |

| swiss chard (raw or cooked) | 11,000 |

| turnip greens (cooked) | 8,440 |

| collard greens (cooked) | 7,694 |

| watercress (raw) | 5,767 |

| garden peas (raw) | 2,593 |

| romaine lettuce | 2,312 |

| zucchini (courgettes) | 2,125 |

| brussels sprouts | 1,590 |

| broccoli, raw | 1,403 |

| pistachio nuts | 1,205 |

| broccoli, cooked | 1,121 |

| carrot (cooked) | 687 |

| maize/corn | 642 |

| egg (hard boiled) | 353 |

| avocado (raw) | 271 |

| carrot (raw) | 256 |

| kiwifruit | 122 |

Safety

[edit]In humans, the Observed Safe Level (OSL) for lutein, based on a non-government organization evaluation, is 20 mg/day.[34] Although much higher levels have been tested without adverse effects and may also be safe, the data for intakes above the OSL are not sufficient for a confident conclusion of long-term safety.[3][34] Neither the U.S. Food and Drug Administration nor the European Food Safety Authority considers lutein an essential nutrient or has acted to set a tolerable upper intake level.[3]

Commercial value

[edit]The lutein market is segmented into pharmaceutical, dietary supplement, food, pet food, and animal and fish feed. The pharmaceutical market for lutein is estimated to be about US$190 million, and the nutraceutical and food categories are estimated to be about US$110 million. Pet food and other animal applications for lutein are estimated at US$175 million annually. This includes chickens (usually in combination with other carotenoids), to get color in egg yolks, and fish farms to color the flesh closer to wild-caught color.[35] In the dietary supplement industry, the major market for lutein is for products with claims of helping maintain eye health.[36] Newer applications are emerging in oral and topical products for skin health. Skin health via orally consumed supplements is one of the fastest growing areas of the US$2 billion carotenoid market.[37]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ MSDS at Carl Roth (Lutein Rotichrom, German).

- ^ "Lutein", Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Carotenoids". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis. July 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ Bernstein, P. S.; Li, B; Vachali, P. P.; Gorusupudi, A; Shyam, R; Henriksen, B. S.; Nolan, J. M. (2015). "Lutein, Zeaxanthin, and meso-Zeaxanthin: The Basic and Clinical Science Underlying Carotenoid-based Nutritional Interventions against Ocular Disease". Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 50: 34–66. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.10.003. PMC 4698241. PMID 26541886.

- ^ Krinksy, Norman; Landrum, John; Bone, Richard (2003). "Biological Mechanisms of the Protective Role of Lutein and Zeaxanthin in the Eye". Annual Review of Nutrition. 23 (1): 171–201. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.23.011702.073307. PMID 12626691.

- ^ "Maintaining color stability". Natural Products Insider, Informa Exhibitions, LLC. 1 August 2006. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ Mary E. Rawles, "The Integumentary System", in A. J. Marshall (ed.), 2012, "Biology and Comparative Physiology of Birds", vol. 1, p. 220. ISBN 9781483263793.

- ^ McGraw KJ, Beebee MD, Hill GE, Parker RS (August 2003). "Lutein-based plumage coloration in songbirds is a consequence of selective pigment incorporation into feathers". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part B, Biochemistry & Molecular Biology. 135 (4): 689–96. doi:10.1016/S1096-4959(03)00164-7. PMID 12892761.

- ^ Gill, Victoria. "Sold for a song: The forest birds captured for their tuneful voices". BBC News. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ a b "NIH study provides clarity on supplements for protection against blinding eye disease". US National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. 5 May 2013. Archived from the original on 15 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ a b "The AREDS Formulation and Age-Related Macular Degeneration". US National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. November 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ Liu R, Wang T, Zhang B, et al. (2014). "Lutein and zeaxanthin supplementation and association with visual function in age-related macular degeneration". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 56 (1): 252–8. doi:10.1167/iovs.14-15553. PMID 25515572.

- ^ Wang X, Jiang C, Zhang Y, et al. (2014). "Role of lutein supplementation in the management of age-related macular degeneration: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Ophthalmic Res. 52 (4): 198–205. doi:10.1159/000363327. PMID 25358528. S2CID 5055854.

- ^ Ma L, Dou HL, Wu YQ, et al. (2012). "Lutein and zeaxanthin intake and the risk of age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Br. J. Nutr. 107 (3): 350–9. doi:10.1017/S0007114511004260. PMID 21899805.

- ^ a b Evans, Jennifer R.; Lawrenson, John G. (13 September 2023). "Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for slowing the progression of age-related macular degeneration". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (9): CD000254. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000254.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 10498493. PMID 37702300.

- ^ "Lutein + Zeaxanthin Content of Selected Foods". Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis. 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ a b SanGiovanni JP, Chew EY, Clemons TE, Ferris FL, Gensler G, Lindblad AS, Milton RC, Seddon JM, Sperduto RD (September 2007). "The relationship of dietary carotenoid and vitamin A, E, and C intake with age-related macular degeneration in a case-control study: AREDS Report No. 22". Archives of Ophthalmology. 125 (9): 1225–32. doi:10.1001/archopht.125.9.1225. PMID 17846363.

- ^ Moeller SM, Voland R, Tinker L, Blodi BA, Klein ML, Gehrs KM, Johnson EJ, Snodderly DM, Wallace RB, Chappell RJ, Parekh N, Ritenbaugh C, Mares JA (2008). "Associations between age-related nuclear cataract and lutein and zeaxanthin in the diet and serum in the Carotenoids in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study, an Ancillary Study of the Women's Health Initiative". Arch Ophthalmol. 126 (3): 354–64. doi:10.1001/archopht.126.3.354. PMC 2562026. PMID 18332316.

- ^ Barker Fm, 2nd (2010). "Dietary supplementation: effects on visual performance and occurrence of AMD and cataracts". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 26 (8): 2011–23. doi:10.1185/03007995.2010.494549. PMID 20590393. S2CID 206965363.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Liu XH, Yu RB, Liu R, Hao ZX, Han CC, Zhu ZH, Ma L (2014). "Association between lutein and zeaxanthin status and the risk of cataract: a meta-analysis". Nutrients. 6 (1): 452–65. doi:10.3390/nu6010452. PMC 3916871. PMID 24451312.

- ^ Ma L, Hao ZX, Liu RR, Yu RB, Shi Q, Pan JP (2014). "A dose-response meta-analysis of dietary lutein and zeaxanthin intake in relation to risk of age-related cataract". Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 252 (1): 63–70. doi:10.1007/s00417-013-2492-3. PMID 24150707. S2CID 13634941.

- ^ Chew EY, SanGiovanni JP, Ferris FL, Wong WT, Agron E, Clemons TE, Sperduto R, Danis R, Chandra SR, Blodi BA, Domalpally A, Elman MJ, Antoszyk AN, Ruby AJ, Orth D, Bressler SB, Fish GE, Hubbard GB, Klein ML, Friberg TR, Rosenfeld PJ, Toth CA, Bernstein P (2013). "Lutein/zeaxanthin for the treatment of age-related cataract: AREDS2 randomized trial report no. 4". JAMA Ophthalmol. 131 (7): 843–50. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.4412. PMC 6774801. PMID 23645227.

- ^ NHANES 2013-2014 survey results, reported as What We Eat In America

- ^ Seddon JM, Ajani UA, Sperduto RD (November 1994). "Dietary carotenoids, vitamins A, C, and E, and advanced age-related macular degeneration. Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group". JAMA. 272 (18): 1413–20. doi:10.1001/jama.272.18.1413. PMID 7933422.

- ^ WHO/FAO Codex Alimentarius General Standard for Food Additives

- ^ UK Food Standards Agency: "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code."Standard 1.2.4 - Labelling of ingredients". 8 September 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ Rajput, N; Naeem, M; Ali, S; Zhang, J F; Zhang, L; Wang, T (1 May 2013). "The effect of dietary supplementation with the natural carotenoids curcumin and lutein on broiler pigmentation and immunity". Poultry Science. 92 (5): 1177–1185. doi:10.3382/ps.2012-02853. PMID 23571326.

- ^ Lokaewmanee, Kanda; Yamauchi, Koh-en; Komori, Tsutomu; Saito, Keiko (2011). "Enhancement of Yolk Color in Raw and Boiled Egg Yolk with Lutein from Marigold Flower Meal and Marigold Flower Extract". Journal of Poultry Science. 48 (1): 25–32. doi:10.2141/jpsa.010059. ISSN 1346-7395. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ^ USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 23 (2010) Archived 3 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Niizu, P.Y.; Delia B. Rodriguez-Amaya (2005). "Flowers and Leaves of Tropaeolum majus L. as Rich Sources of Lutein". Journal of Food Science. 70 (9): S605–S609. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb08336.x. ISSN 1750-3841.

- ^ Eisenhauer, Bronwyn; Natoli, Sharon; Liew, Gerald; Flood, Victoria M. (9 February 2017). "Lutein and Zeaxanthin—Food Sources, Bioavailability and Dietary Variety in Age-Related Macular Degeneration Protection". Nutrients. 9 (2): 120. doi:10.3390/nu9020120. PMC 5331551. PMID 28208784.

- ^ Manke Natchigal, A.; Oliveira Stringheta, A.C.; Corrêa Bertoldi, M.; Stringheta, P.C. (2012). "QUANTIFICATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF LUTEIN FROM TAGETES (TAGETES PATULA L.) AND CALENDULA (CALENDULA OFFICINALIS L.) FLOWERS". Acta Hortic. 939, 309–314. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ a b Shao A, Hathcock JN (2006). "Risk assessment for the carotenoids lutein and lycopene". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 45 (3): 289–98. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2006.05.007. PMID 16814439.

The OSL risk assessment method indicates that the evidence of safety is strong at intakes up to 20mg/d for lutein, and 75 mg/d for lycopene, and these levels are identified as the respective OSLs. Although much higher levels have been tested without adverse effects and may be safe, the data for intakes above these levels are not sufficient for a confident conclusion of long-term safety.

- ^ Lokaewmanee, Kanda & Yamauchi (2011). "Enhancement of Yolk Color in Raw and Boiled Egg Yolk with Lutein from Marigold Flower Meal and Marigold Flower Extract". The Journal of Poultry Science. 48: 25–32. doi:10.2141/jpsa.010059 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Campbell, J. (14 January 2021). "Natural Eye Supplements Care For Your Long-Term Vision". Intechra Health. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ FOD025C The Global Market for Carotenoids, BCC Research