Dudley Carleton, 1st Viscount Dorchester

Dudley Carleton, 1st Viscount Dorchester (10 March 1573 – 15 February 1632) was an English art collector, diplomat and Secretary of State.

Early life

[edit]He was the second son of Anthony Carleton of Brightwell Baldwin, Oxfordshire, and of Joyce Goodwin, daughter of John Goodwin of Winchendon, Buckinghamshire. He was born on 10 March 1573, and educated at Westminster School and Christ Church, Oxford, where he graduated B.A, in 1595, M.A. in 1600.[1] After graduating he took employment with Sir Edward Norreys at Ostend, as secretary.[2] In 1598 he attended Francis Norreys, nephew of Sir Edward, on a diplomatic mission to Paris led by Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham.[3] In 1603 he became secretary to Thomas Parry, ambassador in Paris, but left the position shortly, for one in the household of Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland.[4]

Carleton was returned to the parliament of 1604 as member for St Mawes. As a parliamentarian, Carleton was an apologist for the court line in unpopular causes, as in the debate over the "Apology" of 1604.[5]

Through his connection with the Earl of Northumberland, his name was associated with the Gunpowder Plot in 1605. Carleton was out of the country in November 1605; Francis Norreys (by now Earl of Berkshire) had gone to Spain earlier in the year with the Earl of Nottingham who was Ambassador in Madrid;[6] and Carleton had accompanied him. Norreys fell ill in Paris on the journey home, and Carleton was in Paris when it was discovered that the plotters' house, adjacent to the vault that had contained the gunpowder under Parliament, had been sublet, by Thomas Percy in May 1604, by using the names of Carleton and another member of the Northumberland household.[7] Summoned to return, Carleton was detained for a month, but was released through the influence of Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury.[8] Cecil in fact knew well enough that Carleton had been held up in Paris from September, from letters detailing the treatment of Norreys who was a political ally.[3]

Ambassador to the Venetian Republic

[edit]In 1610 he was knighted and sent as ambassador to Venice, where he was the means of concluding the Treaty of Asti. Much of his work was tied up with religious affairs. While there he sent the ex-Carmelite Giulio Cesare Vanini to England;[9] he also helped Giacomo Castelvetro out the Inquisition's prison in 1611.[10] For the king he commissioned in 1613 a report from Paolo Sarpi on the theology of Conrad Vorstius.[11] On his staff were Isaac Wake, and Nathaniel Brent who would later smuggle Sarpi's history of the Council of Trent out for publication in London.[12]

Carleton as a diplomat had a wide general correspondence, as well as letters from George Abbot, the Archbishop of Canterbury, concerned with English apostates and possible conversions of Catholics.[13] He exchanged information with intelligencers such as Sarpi who had a large network,[14] and recruited informants, such as the Neapolitan jurist Giacomo Antonio Marta.[15] Encouraged by Walter Cope, he began also to look for works of art for Charles, Duke of York and the Earl of Salisbury;[16] Carleton, like his predecessor in Venice Sir Henry Wotton, effectively promoted Italian aesthetics and the Grand Tour to the Stuart upper crust and looked for Venetian works of art that might be acquired by Charles I (then Duke of York) and other members of the Whitehall Group.[17]

Ambassador to the United Provinces

[edit]Carleton returned home in 1615, and next year was appointed ambassador to the Netherlands. Anglo-Dutch relations were central to foreign policy and Carleton succeeded in improving these, through the Amboyna massacre, commercial disputes between the two countries, and the tendency of James I to seek alliance with Spain.

The religious situation in the Netherlands had become fraught, during the Twelve Years' Truce, with the Calvinist–Arminian debate that had taken the form of a clash between Remonstrants and Counter-Remonstrants. Carleton used Matthew Slade as informant, who was a Contra-Remonstrant partisan.[18] Maurice of Nassau supported the Contra-Remonstrants and Calvinist orthodoxy, and was vying for dominance in all seven provinces, resisted by Johan van Oldenbarnevelt who backed the Remonstrants. Carleton was himself an orthodox Genevan Calvinist, who also saw the divisive quarrel as weakening an ally. He weighed in on Maurice's side, and in line with the thinking of Abbot and the king pressed for the national Synod of Dort. His public intervention in the affair of the Balance (a Remonstrant pamphlet criticizing Carleton) represented a crucial escalation of the religious conflict, which strengthened the Contra-Remonstrant cause.[19] A British delegation, which he helped to choose with Abbot, was led by George Carleton, a cousin.[4] The Synod in 1618–9 resolved the theological issue, somewhat in arrears of political developments on the ground but providing the keystone to Maurice's control.

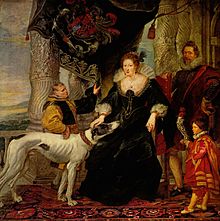

Carleton at the same time continued his interests in the art trade. He exchanged marbles for paintings with Rubens, served as an intermediary for collectors like Lord Somerset, Lord Pembroke, Lord Buckingham and sent Lord Arundel paintings by Daniel Mytens and Gerard van Honthorst.[20]

As the build-up to the Palatinate campaign of 1620 began, Carleton realised the great limitations of the diplomatic line he had been pursuing and the influence he had: Maurice and James had quite different intentions concerning Frederick V, Elector Palatine, who was nephew (respectively son-in-law) to the two men. Maurice, in crude terms, was happy to have war over the border in Germany tying up the Spanish, while James wanted peace. Frederick did as Maurice wished in claiming the crown of Bohemia, was heavily defeated in the Battle of White Mountain and set off the Thirty Years' War, and lost the Palatinate.[21] It was in Carleton's house at The Hague that Frederick and his queen Elizabeth of Bohemia took refuge in 1621.

Carleton returned to England in 1625 with George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, and was made Vice-Chamberlain of the Household and a privy councillor.

In both Houses

[edit]Shortly afterwards he took part in an abortive mission to France in favour of the Huguenots and to inspire a league against the House of Habsburg. On his return in 1626 he found the attention of Parliament, to which he had been elected for Hastings, completely occupied with the attack on Buckingham. Carleton endeavoured to defend his patron, and supported the king's exercise of royal prerogative. On 12 May he warned that the king if thwarted might follow "new counsels".[22]

His further career in the Commons was cut short by his elevation in May to the peerage as Baron Carleton of Imber Court. In the debate over Roger Maynwaring he put the argument that the book being complained of should not be burned, in case the king was offended.[23] Shortly afterwards he was dispatched on another mission to The Hague, on return from which he was created Viscount Dorchester in July 1628. He was active in forwarding the conferences between Buckingham and Contarini for a peace with France on the eve of Buckingham's intended departure for La Rochelle, which was prevented by the Duke's assassination.

The Personal Rule

[edit]In December 1628 Dorchester was made principal Secretary of State, making him a leading figure of the Personal Rule of Charles I. He worked with the efficient bureaucrat Sir John Coke, a master of the paperwork but deliberately excluded from the more arcane foreign negotiations. Dorchester came to full responsibility for matters of foreign policy.[24]

He died on 15 February 1632, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Correspondence

[edit]His surviving letters cover practically the whole history of foreign affairs in the period 1610–1628. His letters as ambassador at The Hague, January 1616 to December 1620, were first edited by Philip Yorke, in 1757; his correspondence from The Hague in 1627 by Sir Thomas Phillipps in 1841; other letters are printed in the letter collection Cabala from the 17th century,[25] and in Thomas Birch's Court and Times of James I and Charles I, but most remained in manuscript among the state papers. His regular correspondent John Chamberlain kept up with Carleton from 1597 to the end of his life in 1628, and 452 of Chamberlain's letters survive.[26] John Hales was employed by Carleton to report on the proceedings of the Synod of Dort, and the correspondence was published in 1659.[27] Carleton and Chamberlain belonged to an intellectual circle including also Thomas Allen, the physician William Gent, William Gilbert and Mark Ridley.[28]

Carleton's letters are considered, in particular, a major source for information on the patronage networks of the period, in terms of their actual functioning. When Carleton's family connection Henry Savile died in 1622, leaving the position of Provost of Eton College vacant, Carleton took great interest in the post on his own behalf (he had expressed an interest to Chamberlain already in 1614). It was supposed to be for a cleric, but Savile was a layman. Thomas Murray became Provost; but he died in 1623. Buckingham would have the last word, and the Spanish match interfered; Carleton played the princess card of the favour of Elizabeth of Bohemia, but the nomination had become a free-for-all. Murray's widow had the provostship for while to help support seven children; Robert Aytoun, rumour had it, might marry her. Carleton gave Buckingham a marble chimney for York House, while his colleague Wotton gave pictures. In the end the post went to Wotton in 1624 who had reversions of legal offices that could be manipulated to satisfy William Becher, another diplomat with his hat in the ring, and with a definite promise from Buckingham.[29]

Family

[edit]Carleton married in November 1607 the widowed Anne, Lady Tredway (née Gerrard), daughter of George Gerrard and Margaret Dacres, Margaret married Henry Savile as her second husband. Anne died in 1627, leaving no living children. He then married in 1630 Anne (née Glemham), widow of Paul Bayning, 1st Viscount Bayning, and daughter of Sir Henry Glemham and Lady Anne Sackville; she died in 1639, and their one child died young. The title Viscount Dorchester died with him.[4][30] His heirs were the sons of his elder brother, George: Sir John Carleton, 1st Baronet and John's half-brother Sir Dudley Carleton.

See also

[edit]- Baron Dorchester

- Viscount Bayning

- Secretary of State (England)

- Vice-Chamberlain of the Household

- Privy council

References

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Dorchester, Dudley Carleton, Viscount". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Carleton, Dudley, Lord (CRLN626D)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ a b Hugh Trevor-Roper, Europe's Physician: The Various Life of Sir Theodore de Mayerne (2006), p. 103.

- ^ a b c Reeve, L. J. "Carleton, Dudley". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4670. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Theodore K. Rabb, Jacobean Gentleman: Sir Edwin Sandys, 1561–1629 (1998), p. 105.

- ^ Dictionary of National Biography, Norris, Francis, Earl of Berkshire (1579–1623), by Sidney Lee. Published 1894.

- ^ Nicholls, Mark. "Fawkes, Guy". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9230. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Dictionary of National Biography, Carleton, Sir Dudley, Viscount Dorchester (1573–1632), diplomatist, by Augustus Jessopp. Published 1886.

- ^ Galileo Project Page

- ^ Martin, John. "Castelvetro, Giacomo". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50429. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ David Wootton, Paolo Sarpi: Between Renaissance and Enlightenment (2002), p. 91; Google Books.

- ^ Hegarty, A. J. "Brent, Sir Nathaniel". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3324. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ James Doelman, King James I and the Religious Culture of England (2000), p. 105; Internet Archive.

- ^ Joad Raymond, News Networks in Seventeenth Century Britain and Europe, p. 38; Google Books.

- ^ Paul F. Grendler, The University of Mantua, the Gonzaga and the Jesuits, 1584–1630 (2009), p. 99; Google Books.

- ^ Jeremy Brotton, The Sale of the Late King's Goods (2007) pp. 41–2.

- ^ Linda Levy Peck, Consuming Splendor: society and culture in seventeenth-century England (2005), p. 174; Google Books.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ Helmer Helmers, "English public diplomacy in the Dutch Republic, 1609–1619", The Seventeenth Century 36:3 (2021), 413-437. [1]

- ^ M. F. S. Hervey, The Life, Correspondence and Collections of Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, Cambridge 1921, p. 297.

- ^ Jonathan I. Israel, The Dutch Republic (1998), p. 469.

- ^ Glenn Burgess, The Politics of the Ancient Constitution (1992), p. 181.

- ^ J. P. Sommerville, Politics and Ideology in England 1603–1640 (1986), p. 130.

- ^ Kevin Sharpe, The Personal Rule of Charles I (1992) pp. 154–5.

- ^ Cabala: sive scrinia sacra: Mysteries of state and government in letters of illustrious persons and great agents in the reigns of Henry the Eighth, Queen Elizabeth, K: James, and the late King Charls: In two parts, in which the secrets of empire and public manage of affairs are contained: With many remarkable passages no where else published (1654); archive.org.

- ^ Finkelpearl, P. J. "Chamberlain, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5046. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Greenslade, Basil. "Hales, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11914. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Mordechai Feingold (1984). The Mathematicians' Apprenticeship: Science, Universities and Society in England, 1560–1640. CUP Archive. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-521-25133-4. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ Linda Levy Peck, Court Patronage and Corruption in Early Stuart England (1993), pp. 62–67.

- ^ Goulding, R. D. "Savile, Sir Henry". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24737. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

[edit]- memorial in Westminster Abbey

- "Archival material relating to Dudley Carleton, 1st Viscount Dorchester". UK National Archives.

- Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Dorchester, Dudley Carleton, Viscount". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 421–422.

- 1573 births

- 1632 deaths

- 16th-century English nobility

- 17th-century English diplomats

- Ambassadors of England to the Netherlands

- Ambassadors of England to the Republic of Venice

- Burials at Westminster Abbey

- English MPs 1604–1611

- English MPs 1626

- Members of the pre-1707 English Parliament for constituencies in Cornwall

- Peers of England created by Charles I

- Nobility from Oxfordshire

- Secretaries of state of the Kingdom of England

- Viscounts in the Peerage of England