Drepanosaurus

| Drepanosaurus Temporal range: Late Triassic

| |

|---|---|

| |

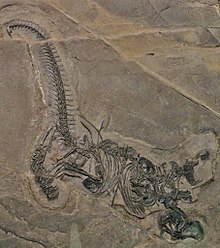

| Fossil | |

| |

| Sketetal diagram scale bar = 1 cm | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | †Drepanosauromorpha |

| Family: | †Drepanosauridae |

| Genus: | †Drepanosaurus Pinna, 1979 |

| Species: | †D. unguicaudatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Drepanosaurus unguicaudatus Pinna, 1979

| |

Drepanosaurus (/drəˌpænəˈsɔːrəs/; "sickle lizard") is a genus of arboreal (tree-dwelling) reptile that lived during the Triassic Period. It is a member of the Drepanosauridae, a group of diapsid reptiles known for their prehensile tails. Drepanosaurus was probably an insectivore, and lived in a coastal environment in what is now modern day Italy, as well as in a streamside environment in the southwestern United States.

Description

[edit]

Drepanosaurus is known to have a huge claw on the "index finger" (digit II) of each hand along with the tail claw. The skull of Drepanosaurus has never been found and is still unknown; however, the skull of Drepanosaurus was likely similar to other drepanosaurs, such as Megalancosaurus. Megalancosaurus' skull was approximately the same size as its enlarged claws, and had a bird-like jaw and head shape.[1]

The forelimb of Drepanosaurus is highly modified compared to other vertebrates. Its ulna was modified into a robust, crescent-shaped site for muscle attachment. The elongated carpal bone functionally replaced the ulna. Additional forelimb musculature would have attached to the withers.[2] The animal's second digit bore a large claw, reminiscent of those found in dinosaurs such as Noasaurus and Baryonyx. However, it is more likely that Drepanosaurus used its claw like the modern pygmy anteater, tearing through bark and insect nests to find invertebrate prey. Some researchers have forwarded the more far-fetched proposal that the claw was used to excavate burrows, but this is not unanimously agreed upon.[3]

The dorsal neural spine humps of Drepanosaurus are much taller along all succeeding spines reaching down to the sacrum. Sacral and anterior caudal neural spines are very low, if present at all, and neural spines are elongated, showing expanded dorsal margins after those areas. The scapula was robust with a 70 degree bend. The humerus and radius were short, while the ulna was replaced by an ulnare and shifted to the elbow, taking a disc-like form. This skeletal configuration change is thought to have adapted as a result of the large claw on digit II requiring a large muscle in order to operate. The pelvis was large with the pubis forming the majority of the ventral portion. The hind limbs of Drepanosaurus were much larger than the forelimbs, with the tibia and fibula being broadly separated.[4]

Discovery and classification

[edit]Discovered in northern Italy in 1979, Drepanosaurus was named by Giovanni Pinna, a paleontologist and museologist.[5] The species name is Drepanosaurus unguicaudatus.[6] It is derived from the Greek for "sickle lizard." Only one incomplete adult specimen has been found. Another partial specimen of Drepanosaurus was found in New Mexico's Chinle Formation in 2016.[7]

Drepanosaurus is part of the clade Drepanosauridae, which is nested in the larger clade Drepanosauromorpha. Drepanosauromorphs are sometimes considered part of the group Protorosauria which may or may not be a natural group (i.e., monophyletic). In any case, it is clear that drepanosaurs are diapsid reptiles.

Paleobiology

[edit]

Drepanosaurus is hypothesized to have been an insectivore, using the claws on the second digits to lift bark and dig into crevices and grooves on trees to find insects.

It has been suggested that Drepanosaurus was also a digging animal, and could use the clawed tail as a tool for unearthing insects. However, it is not thought that Drepanosaurus's tail was flexible enough to be used for digging, especially since many characteristics point to an arboreal lifestyle.

Paleoecology

[edit]

Being only 45–50 centimetres (18–20 in) in length, Drepanosaurus likely spent its time in trees using its clawed hands and feet to climb from branch to branch, as well as its prehensile tail, much like a chameleon. The claw on the tip of the tail may have also been used to grip branches.[5] Drepanosaurus is much larger than its relatives, more than double the length of Megalancosaurus. Most drepanosaurs are thought to be tree-dwelling insectivores with similar body structures to Drepanosaurus, except for minor differences usually dealing with forelimb configuration and head shape disparities.

Drepanosaurus inhabited forests in what is now northern Italy. Relatives have been found in other parts of Italy and New Mexico, as well as New Jersey, in similar paleoenvironments.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wedel, M. (2007). "Drepanosauromorpha, the "monkey lizards"". ucmp.berkeley.edu.

- ^ Harris, J.D.; Downs, A. (2002). "A drepanosaurid pectoral girdle from the Ghost Ranch (Whitaker) Coelophysis Quarry (Chinle Group, Rock Point Formation, Rhaetian), New Mexico". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (1): 70–75. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0070:ADPGFT]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 53339494.

- ^ Renestò, S.; Fraser, N.C. (2010). "Drepanosaurid (Reptilia: Diapsida) remains from a Late Triassic fissure infilling at Cromhall Quarry (Avon, Great Britain)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (3): 703–705. doi:10.1671/A1101. S2CID 128645833.

- ^ Renestò, S. (1994). "The shoulder girdle and anterior limb of Drepanosaurus unguicaudatus (Reptilia, Neodiapsida) from the upper Triassic (Norian) of Northern Italy". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 111 (3): 247–264. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1994.tb01485.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ a b Pinna, G. (1980). "Drepanosaurus unguicaudatus, nuovo genere e nuova specie di Lepidosauro del trias alpino". Atti della Soc Ital di Sci Nat del Mus Civ di Storia Nat di Milano. 121: 181–192.

- ^ Senter, P. (2004). "Phylogeny of Drepanosauridae (Reptilia: Diapsida)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 2 (3): 257–268. doi:10.1017/S1477201904001427. ISSN 1477-2019. S2CID 83840423.

- ^ Pritchard, Adam C.; Turner, Alan H.; Irmis, Randall B.; Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Smith, Nathan D. (2016). "Extreme Modification of the Tetrapod Forelimb in a Triassic Diapsid Reptile". Current Biology. 26 (20): 2779–2786. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.084. ISSN 0960-9822.

- ^ Colbert, Edwin H.; Olsen, Paul E. (2001). "A New and Unusual Aquatic Reptile from the Lockatong Formation of New Jersey (Late Triassic, Newark Supergroup)". American Museum Novitates. 3334: 1–24. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2001)334<0001:ANAUAR>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0003-0082.