SpaceX Dragon

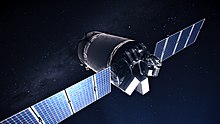

Dragon is a family of spacecraft developed and produced by American private space transportation company SpaceX.

The first variant, later named Dragon 1, flew 23 cargo missions to the International Space Station (ISS) between 2010 and 2020 before retiring. Design of this version, not designed to carry astronauts, was funded by NASA with $396 million awarded through the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services program and contracted to ferry cargo under the Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) program.

An improved version, the Dragon 2, was introduced in 2019 and has both crewed and cargo versions. The first un-crewed flight test (Demo-1) took place in March 2019, followed by a crewed flight test (Demo-2) in May 2020. Since those flight tests, the Crew Dragon has become one of the primary spacecraft ferrying crew to and from the ISS. While the Cargo Dragon continues to carry cargo under the CRS program.

SpaceX has also proposed versions named Red Dragon for Mars exploration and Dragon XL to provide Gateway Logistics Services to the Lunar Gateway.

Name

[edit]SpaceX's CEO, Elon Musk, named the spacecraft after the 1963 song "Puff, the Magic Dragon" by Peter, Paul and Mary, reportedly as a response to critics who considered his spaceflight projects impossible.[1] Early on, it had been named Magic Dragon, and t-shirts had been printed with this name.[2] As late as September 2012, SpaceX board member Steve Jurvetson was still referring to it as "The Magic Dragon, Puffed to the sea."[3] That was his caption to a photo of the capsule several months after it had completed its COTS 2 demo flight where the spacecraft had accomplished its first docking with the ISS. This song, ostensibly composed for children, had long been associated with perceived references to smoking marijuana. In 2008, Elon Musk confirmed that the association between the song and marijuana was the reason behind the name Dragon, saying that "so many people thought I [must be] smoking weed to do this venture."[4]

Dragon 1

[edit]Dragon 1 was the original Dragon iteration, providing cargo service to the ISS. It flew 23 missions between 2010 and 2020, when it was retired. On May 25, 2012, NASA astronaut Don Pettit operated the Canadarm2 to grapple the first SpaceX Dragon and berth it to the Harmony module. This marked the first time a private spacecraft had ever rendezvoused with the ISS. The Dragon capsule was carrying supplies for the ISS, and the successful capture demonstrated the feasibility of using privately developed spacecraft to resupply the station. Pettit was also the first to enter the uncrewed supply ship on May 26, making him the first astronaut in the history of space exploration to successfully enter a commercially-built and operated spacecraft in orbit. During the capture, he was quoted saying, "Houston, Station, we've got us a dragon by the tail."

Dragon 2

[edit]

An improved version, the Dragon 2, was introduced in 2019 and has two versions: Crew Dragon and Cargo Dragon. The first un-crewed flight test (Demo-1) took place in March 2019, followed by a crewed flight test (Demo-2) in May 2020.

The Crew Dragon is one of the primary spacecraft ferrying crew members to and from the ISS and on private missions. The Cargo Dragon carries cargo to the ISS under the CRS program.

Red Dragon

[edit]Red Dragon was a cancelled version of the Dragon spacecraft that had been previously proposed to fly farther than Earth orbit and transit to Mars via interplanetary space. In addition to SpaceX's own privately funded plans for an eventual Mars mission, NASA Ames Research Center had developed a concept called Red Dragon. Red Dragon was to be a low-cost Mars mission that would use Falcon Heavy as the launch vehicle and trans-Martian injection vehicle, and the SpaceX Dragon 2-based capsule to enter the atmosphere of Mars. The concept was originally envisioned for launch in 2018 as a NASA Discovery mission, then alternatively for 2022, but was never formally submitted for funding within NASA.[5] The mission would have been designed to return samples from Mars to Earth at a fraction of the cost of NASA's own sample-return mission, which was projected in 2015 to cost US$6 billion.[5]

On 27 April 2016, SpaceX announced its plan to go ahead and launch a modified Dragon lander to Mars in 2018.[6][7] However, Musk cancelled the Red Dragon program in July 2017 to focus on developing the Starship system instead.[8][9] The modified Red Dragon capsule would have performed all entry, descent and landing (EDL) functions needed to deliver payloads of 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb) or more to the Martian surface without using a parachute. Preliminary analysis showed that the capsule's atmospheric drag would slow it enough for the final stage of its descent to be within the abilities of its SuperDraco retro-propulsion thrusters.[10][11]

Dragon XL

[edit]

On 27 March 2020, SpaceX revealed the Dragon XL resupply spacecraft to carry pressurized and unpressurized cargo, experiments and other supplies to NASA's planned Lunar Gateway under a Gateway Logistics Services (GLS) contract.[12][13] The equipment delivered by Dragon XL missions could include sample collection materials, spacesuits and other items astronauts may need on the Gateway and on the surface of the Moon, according to NASA. It will launch on SpaceX Falcon Heavy rockets from LC-39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.[14]

The Dragon XL will stay at the Gateway for 6 to 12 months at a time, when research payloads inside and outside the cargo vessel could be operated remotely, even when crews are not present.[14] Its payload capacity is expected to be more than 5,000 kilograms (11,000 lb) to lunar orbit.[15] There is no requirement for a return to Earth. At the end of the mission the Dragon XL must be able to undock and dispose of the same mass it can bring to the Gateway, by moving the spacecraft to a heliocentric orbit.[16]

On February 22, 2023, NASA discussed the Dragon XL's development for the first time since its 2020 unveiling, with Mark Wiese, NASA's manager of deep space logistics for the Gateway program, answering during a panel at SpaceCom that NASA has been working with SpaceX to run a series of studies to refine the Dragon XL design and examine cargo configurations and other capabilities that could be enabled by the spacecraft.[17] Wiese also elaborated that Dragon XL would be used for initial missions, and stating that “[NASA] talked to [SpaceX] about Starship evolution and how it all worked together, but we’re not there yet because it's still in a development phase” insinuating that Starship will eventually replace Dragon XL once it completes development.[17]

On March 29, 2024, NASA released an article outlining the mission of Artemis IV, which is to be the first crewed mission to the Lunar Gateway slated for 2028, stating that the Dragon XL will be used to resupply and carry science experiments, however, Artemis IV will take place concurrently with a Starship launch which will dock at the Gateway and help with the assembly of the station.[18]

See also

[edit]- Comparison of space station cargo vehicles

- List of human spaceflight programs

- Space Shuttle successors

References

[edit]- ^ "5 Fun Facts About Private Rocket Company SpaceX". Space.com. 21 May 2012. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ Tom Markusic, founder of Firefly Aerospace, explains the name of the Dragon spacecraft during his early days working at Space X (YouTube video of Nov 14, 2022 lecture at the University of Texas at Austin, Aerospace Engineering Department, published Nov 17, 2022)

- ^ Jurvetson, Steve (7 September 2012). "The Magic Dragon". Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Elon Musk, CEO and CTO, Space Exploration Technologies Corp (SpaceX) explains how he picked the names 'Falcon' and 'Dragon', Google Zeitgeist'08 talk "10 Years In / 10 Years Out", September 18, 2008 (YouTube, published on Sep 22, 2008)

- ^ a b Wall, Mike (10 September 2015). ""Red Dragon" Mars Sample-Return Mission Could Launch by 2022". Space.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ @SpaceX (27 April 2016). "Planning to send Dragon to Mars as soon as 2018. Red Dragons will inform overall Mars architecture, details to come" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Newmann, Dava (27 April 2016). "Exploring Together". blogs.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Berger, Eric (19 July 2017). "SpaceX appears to have pulled the plug on its Red Dragon plans". arstechnica.com. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ Grush, Loren (19 July 2017). "Elon Musk suggests SpaceX is scrapping its plans to land Dragon capsules on Mars". The Verge. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Wall, Mike (31 July 2011). ""Red Dragon" Mission Mulled as Cheap Search for Mars Life". Space.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ "NASA ADVISORY COUNCIL (NAC) – Science Committee Report" (PDF). NASA Ames Research Center. 1 November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Potter, Sean (27 March 2020). "NASA Awards Artemis Contract for Gateway Logistics Services". NASA. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (27 March 2020). "SpaceX wins NASA commercial cargo contract for lunar Gateway". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen. "NASA picks SpaceX to deliver cargo to Gateway station in lunar orbit". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "Dragon XL revealed as NASA ties SpaceX to Lunar Gateway supply contract". 27 March 2020. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "NASA delays starting contract with SpaceX for Gateway cargo services". 15 April 2021. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ a b Foust, Jeff (24 February 2023). "NASA plans to start work this year on first Gateway logistics mission". SpaceNews. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- ^ Hambleton, Kathryn; Williams, Catherine E. (29 March 2024). "NASA's Artemis IV: Building First Lunar Space Station". NASA. Retrieved 4 June 2024.