Draft:Wartime Premiership of H.H. Asquith

| An editor has marked this as a promising draft and requests that, should it go unedited for six months, G13 deletion be postponed, either by making a dummy/minor edit to the page, or by improving and submitting it for review. Last edited by Paulturtle (talk | contribs) 2 days ago. (Update) |

| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about yourself, your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by Paulturtle (talk | contribs) 2 days ago. (Update) |

The Earl of Oxford and Asquith | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |

| In office 5 April 1908 – 5 December 1916 | |

| Monarchs | |

| Preceded by | Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman |

| Succeeded by | David Lloyd George |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

| In office 10 December 1905 – 12 April 1908 | |

| Prime Minister | Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman |

| Preceded by | Austen Chamberlain |

| Succeeded by | David Lloyd George |

| Home Secretary | |

| In office 18 August 1892 – 25 June 1895 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Henry Matthews |

| Succeeded by | Matthew White Ridley |

| Secretary of State for War | |

| In office 30 March 1914 – 5 August 1914 | |

| Preceded by | J. E. B. Seely |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Kitchener |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office 12 February 1920 – 21 November 1922 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Donald Maclean |

| Succeeded by | Ramsay MacDonald |

| In office 6 December 1916 – 14 December 1918 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George |

| Preceded by | Sir Edward Carson |

| Succeeded by | Donald Maclean |

| Leader of the Liberal Party | |

| In office 30 April 1908 – 14 October 1926 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman |

| Succeeded by | David Lloyd George |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Herbert Asquith 12 September 1852 Morley, West Riding of Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 15 February 1928 (aged 75) Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire, England |

| Resting place | All Saints' Church, Sutton Courtenay |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 10, including Raymond, Herbert, Arthur, Violet, Cyril, Elizabeth, Anthony |

| Education | |

| Profession | Barrister |

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, KG, PC, KC, FRS (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, served as the Liberal Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 until 1916, the last to lead that party in government without a coalition. Asquith took the United Kingdom into the First World War, but resigned amid political conflict in December 1916 and was succeeded by his War Secretary David Lloyd George.

Stalemate brought deepening resentment against the government, and against Asquith personally, as the population at large and the press lords in particular, blamed him for a lack of energy in the prosecution of the war.[1] It also created divisions within the Cabinet between the "Westerners", including Asquith, who supported the generals in believing that the key to victory lay in ever greater investment of men and munitions in France and Belgium,[2] and the "Easterners", led by Churchill and Lloyd George, who believed that the Western Front was in a state of irreversible stasis and sought victory through action in the East.[3] Lastly, it highlighted divisions between those politicians, and newspaper owners, who thought that military strategy and actions should be determined by the generals, and those who thought politicians should make those decisions.[4] Asquith's view was made clear in his memoirs: "Once the governing objectives have been decided by Ministers at home – the execution should always be left to the untrammeled discretion of the commanders on the spot."[5] Lloyd George's counter view was expressed in a letter of early 1916 in which he asked "whether I have a right to express an independent view on the War or must (be) a pure advocate of opinions expressed by my military advisers?"[6] These divergent opinions lay behind the two great crises that would, within 14 months, see the collapse of the last ever fully Liberal administration and the advent of the first coalition, the Dardanelles Campaign and the Shell Crisis.[7]

Words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words words.

Outbreak of the war

[edit]British attempt to broker peace

[edit]

Unlike the apparently inexorable slide to war between March and September 1939, war in 1914 came relatively suddenly after a few weeks of crisis.[8] The British political world was focussed on the crisis in Ulster, whilst the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in Sarajevo on 28 June had been little noticed in Britain, and had soon been chased off the front pages by the death of Joseph Chamberlain.[9]

Cassar considers that initially: "The country was overwhelmingly opposed to intervention."[10] Much of Asquith's cabinet was similarly inclined, Lloyd George writing in his memoirs: "The Cabinet was hopelessly divided – fully one third, if not one half, being opposed to our entry into the War."[11] Lloyd George himself was largely opposed, and as late as 27 July, he told a journalist; "There could be no question of our taking part in any war in the first instance. He knew of no Minister who would be in favour of it."[12]

After nearly a month, the crisis escalated with Austria-Hungary's ultimatum to Serbia on 23 July, for which an answer was required by 25 July; it was soon clear that Serbia would accept most of the demands but that Austria-Hungary would settle for nothing less than complete capitulation. On 24 July Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey proposed a four-power conference of Britain, France, Italy and Germany to mediate between Austria-Hungary and Russia, Serbia's patron; Asquith reported to the King that the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum could well lead to a continental war, but that he expected the UK to stay out.[8][9] On 24 July he wrote to Venetia; "We are within measurable, or imaginable, distance of a real Armageddon. Happily there seems to be no reason why we should be anything more than spectators."[13] Grey again proposed a four-power conference on 26 July. On Sunday 26 July Asquith wrote that “The curious thing is that on many, if not most, of the points Austria has a good and Servia (sic) a very bad case. But the Austrians are quite the stupidest people (as the Italians are the most perfidious) … many people will think that it is a case of a Big Power wantonly bullying a little one.”[8][9] Grey's attempt to broker peace was rejected by Germany as "not practicable".[12]

Asquith keeps Britain's options open

[edit]On Monday 27 July Asquith was busy with Ireland.[14] After the collapse of Grey’s plan for four-power talks on Tuesday 28 July, it was clear that hostilities on the continent were now very likely, although it was still not yet certain what form they would take or whether Britain should be involved. After dinner with Churchill and the Russian Ambassador Asquith went to the Foreign Office for late night talks with Grey and Haldane.[14]

During the continuing escalation Asquith "used all his experience and authority to keep his options open"[15] On Wednesday 29 July, the day after Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, two decisions were taken at Cabinet. Firstly, the Armed Forces were placed on alert: the “Precautionary Period” was declared and the War Book which Haldane had long prepared was opened at 2pm. Secondly, the Cabinet agreed to guarantee the neutrality of Belgium, as Gladstone's Government had done during the Franco-Prussian War, but Asquith informed the King that Britain’s response to any violation of Belgian neutrality would be decided on grounds of policy rather than strict legality. Grey was authorised to tell the German and French ambassadors that Britain had not yet made a decision as to whether or on what terms to join in or stand aside. Asquith wrote to Venetia (29 July) that he wanted Britain to keep out if possible, but that no formal announcement to that effect would be made:[16][17] "The worst thing we could do would be to announce to the world at the present moment that in no circumstances would we intervene."[18]

Asquith and Grey shared a commitment to Anglo-French unity and believed that openly backing France and Russia would make them more intransigent, without necessarily deterring Germany, but Asquith's caution was also motivated by a need to keep the Liberal Party united. Arthur Ponsonby MP presented Grey with a petition (29 July) to stay out from 22 Liberal backbenchers, and next day he told Asquith that as many as nine tenths of the Liberal Party opposed intervention.[16][17] A party truce was provisionally agreed between Asquith and Bonar Law on 30 July.[19] All the Liberal press apart from the Westminster Gazette wanted Britain to stay out; the Manchester Guardian (31 July) attacked the way in which Britain appeared to have been secretly committed to the side of France and Tsarist Russia - the latter regime was deeply unpopular with Liberal opinion.[16][17]

On the night of Friday 31 July Asquith, who had cancelled his plans to get away to Anglesey for the weekend, drafted a personal appeal from the King to the Tsar to stop the Russian mobilisation against Austria-Hungary which had begun the previous day, after a hint from the embassy in Berlin that this might help to dampen German bellicosity. He took it to the Palace and had the King woken to sign it.[20]

Saturday 1 August saw a difficult Cabinet from 11am to 1.30pm. Morley and Simon apparently wanted Britain to stay out, whilst Grey threatened to resign if the Cabinet pledged not to intervene under any circumstances. Churchill (First Lord of the Admiralty) was bellicose and (according to Asquith) talked for at least half of the meeting, whereas Lloyd George was “more sensible and statesmanlike” and favoured keeping Britain’s options open at the moment. Asquith himself still wanted to keep out but reckoned he would have to resign if Grey did. (CHECK PRIMARY SOURCE TO GET EXACTLY WHAT HE SAID)[21][22]

Continental war

[edit]The German Kaiser issued an ultimatum to Russia and France late on 1 August.[23] From this point Asquith recognised the inevitability of war[24] and committed himself to participation, despite continuing Cabinet opposition; "There is a strong party reinforced by Ll George[,] Morley and Harcourt who are against any kind of intervention. Grey will never consent and I shall not separate myself from him."[25] On Sunday 2 August the German Ambassador Prince Lichnowsky called on Asquith over breakfast and begged him not to intervene in the impending war; Asquith replied it was up to Germany not to invade Belgium or to attack the French coast.[26]

The first of two Cabinets on Sunday 2 August was from 11am to 2pm. Grey informed his colleagues that the French fleet was concentrated in the Mediterranean under an Anglo-French naval agreement of 1912, and after much difficulty it was agreed that Grey should tell the French Ambassador Paul Cambon and the Germans that the Royal Navy would not allow the German navy to conduct hostile operations in the Channel. John Burns resigned, although he was persuaded to stay until the evening. Asquith secured agreement to mobilise the fleet.[27][28][26]

Seven of the Cabinet doves met at Beauchamp’s house for lunch that day.[14] Lloyd George now seemed to be siding with the doves, whilst Asquith's priority was to stick with Grey. Crewe, McKenna and Samuel formed a third, more moderate group. Bonar Law then sent a letter on behalf of the Conservatives offering full support if the government backed France and Russia; Asquith replied that the government was under no obligation, real or implied, to help them. A second Cabinet was held from 6.30pm to 8pm that evening. On the way back from dinner at Reginald McKenna’s house Asquith saw the crowds swarming around Buckingham Palace, and recalled Robert Walpole’s saying “Now they are ringing the bells; in a few weeks they’ll be wringing their hands”.[29][28]

Britain goes to war

[edit]On the morning of Monday 3 August Asquith received letters of resignation from Morley and Simon; Beauchamp turned up to that morning's Cabinet meeting but resigned "in person". Lloyd George held back, moved by news that Belgium had rejected Germany’s ultimatum demanding passage for her army across her soil, and was going to fight. Asquith persuaded the four resignees to sit on the front bench during Grey’s hour long speech in the House of Common that afternoon.[30][31] Grey spoke "with gravity and unexpected eloquence,"[30] and called for British action "against the unmeasured aggrandisement of any power".[32] Liddell Hart considered that this speech saw the "hardening (of) British opinion to the point of intervention".[33] Asquith received a visit from Bonar Law who was worried that the party truce might lead to “jiggery pokery” over Home Rule and Welsh Disestablishment.[30][31]

Another Cabinet was held on the morning of Tuesday 4 August. News that German troops had invaded Belgium allowed Asquith to lead an almost united Liberal Party to war. Sir John Simon (to whom Asquith had written the previous evening imploring him to stay) and Lord Beauchamp agreed not to resign ("a slump in resignations" as Asquith put it). John Morley and John Burns did resign and did not attend Cabinet. Asquith visited the King and then in the afternoon the House of Commons was informed that an ultimatum had been given to Germany expiring midnight Berlin time (11pm London time).[34][35] Margot Asquith described the moment of expiry: "(I joined) Henry in the Cabinet room. Lord Crewe and Sir Edward Grey were already there and we sat smoking cigarettes in silence ... The clock on the mantelpiece hammered out the hour and when the last beat of midnight (sic) struck it was as silent as dawn. We were at War."[36]

Final months of the Liberal government: August 1914 – May 1915

[edit]Asquith's wartime Liberal government

[edit]With other parties promising to co-operate, Asquith's government declared war on behalf of a united nation, Asquith bringing "the country into war without civil disturbance or political schism".[37]

The first months of the War saw a revival in Asquith's popularity. Bitterness from earlier struggles temporarily receded and the nation looked to Asquith, "steady, massive, self-reliant and unswerving",[38] to lead them to victory. But Asquith's peacetime strengths ill-equipped him for what was to become perhaps the first total war and, before its end, he would be out of office forever and his party would never again form a majority government.[39]

Beyond the replacement of Morley and Burns,[40] Asquith made one other significant change to his cabinet. He relinquished the War Office and appointed the non-partisan but Tory-inclined Lord Kitchener of Khartoum.[41] Kitchener was a figure of national renown and his participation strengthened the reputation of the government.[42] Whether it increased its effectiveness is less certain.[43] Overall, it was a government of considerable talent with Lloyd George remaining as chancellor,[44] Grey as Foreign Secretary,[45] and Churchill at the Admiralty.[41]

The invasion of Belgium by German forces, the touch paper for British intervention, saw the Kaiser's armies attempt a lightning strike through Belgium against France, while holding Russian forces on the Eastern Front.[46] To support the French, Asquith's cabinet authorised the despatch of the British Expeditionary Force.[47] The ensuing Battle of the Frontiers in the late summer and early autumn of 1914 saw the final halt of the German advance at the First Battle of the Marne, which established the pattern of attritional trench warfare on the Western Front that continued until 1918.[48]

Dardanelles Campaign

[edit]

The Dardanelles Campaign was an attempt by those favouring an Eastern strategy to end the stalemate on the Western Front.[49] It envisaged an Anglo-French landing on Turkey's Gallipoli Peninsula and a rapid advance to Constantinople which would see the exit of Turkey from the conflict.[50] However, the plan never enjoyed the full support of Admiral Fisher, the First Sea Lord,[51] or of Kitchener and, rather than providing decisive leadership, Asquith sought to arbitrate between these two and Churchill, leading to procrastination and delay.[52] After an initial failed attempt to force the Dardanelles by naval gunfire, Allied troops established bridgeheads on the Gallipoli Peninsula, but a delay in providing sufficient reinforcements allowed the Turks to regroup, leading to a stalemate Jenkins described "as immobile as that which prevailed on the Western Front".[52]

Shell Crisis of May 1915

[edit]The opening of 1915 saw growing division between Lloyd George and Kitchener over the supply of munitions for the army. Lloyd George considered that a munitions department, under his control, was essential to coordinate "the nation's entire engineering capacity".[53] Kitchener favoured the continuance of the current arrangement whereby munitions were sourced through contracts between the War Office and the country's armaments manufacturers. As so often, Asquith sought compromise through committee, establishing a group to "consider the much vexed question of putting the contracts for munitions on a proper footing".[54] This did little to dampen press criticism[55] and, on 20 April, Asquith sought to challenge his detractors in a major speech at Newcastle; "I saw a statement the other day that the operations of our army were being crippled by our failure to provide the necessary ammunition. There is not a word of truth in that statement."[56]

The press response was savage: 14 May 1915 saw the publication in The Times of a letter from their correspondent Charles à Court Repington which ascribed the British failure at the Battle of Aubers Ridge to a shortage of high explosive shells. Thus opened a fully-fledged crisis, the Shell Crisis. The prime minister's wife correctly identified her husband's chief opponent, the Press baron, and owner of The Times, Lord Northcliffe; "I'm quite sure Northcliffe is at the bottom of all this,"[57] but failed to recognise the clandestine involvement of Sir John French, who leaked the details of the shells shortage to Repington.[58] Northcliffe claimed that "the whole question of the supply of the munitions of war is one on which the Cabinet cannot be arraigned too sharply."[59] Attacks on the government and on Asquith's personal lethargy came from the left as well as the right, C. P. Scott, the editor of The Manchester Guardian writing; "The Government has failed most frightfully and discreditably in the matter of munitions."[60]

Other events

[edit]Failures in both the East and the West began a tide of events that was to overwhelm Asquith's Liberal Government.[61] Strategic setbacks combined with a shattering personal blow when, on 12 May 1915, Venetia Stanley announced her engagement to Edwin Montagu. Asquith's reply was immediate and brief, "As you know well, this breaks my heart. I couldn't bear to come and see you. I can only pray God to bless you – and help me."[62] Venetia's importance to him is illustrated by a letter written in mid-1914; "Keep close to me beloved in this most critical time of my life. I know you will not fail."[63] Her engagement; "a very treacherous return after all the joy you've given me", left him devastated.[64] Significant though the loss was personally, its impact on Asquith politically can be overstated.[65] The historian Stephen Koss notes that Asquith "was always able to divide his public and private lives into separate compartments (and) soon found new confidantes to whom he was writing with no less frequency, ardour and indiscretion."[66]

This personal loss was immediately followed, on 15 May, by the resignation of Admiral Fisher after continuing disagreements with Churchill and in frustration at the disappointing developments in Gallipoli.[67] Aged 74, Fisher's behaviour had grown increasingly erratic and, in frequent letters to Lloyd George, he gave vent to his frustrations with the First Lord of the Admiralty; "Fisher writes to me every day or two to let me know how things are going. He has a great deal of trouble with his chief, who is always wanting to do something big and striking."[68] Adverse events, press hostility, Tory opposition and personal sorrows assailed Asquith, and his position was further weakened by his Liberal colleagues. Cassar considers that Lloyd George displayed a distinct lack of loyalty,[69] and Koss writes of the contemporary rumours that Churchill had "been up to his old game of intriguing all round" and reports a claim that Churchill "unquestionably inspired" the Repington Letter, in collusion with Sir John French.[70] Lacking cohesion internally, and attacked from without, Asquith determined that his government could not continue and he wrote to the King, "I have come decidedly to the conclusion that the [Government] must be reconstituted on a broad and non-party basis."[71]

First Coalition: May 1915 – December 1916

[edit]

The formation of the First Coalition saw Asquith display the political acuteness that seemed to have deserted him.[72] But it came at a cost. This involved the sacrifice of two old political comrades: Churchill, who was blamed for the Dardanelles fiasco, and Haldane, who was wrongly accused in the press of pro-German sympathies.[71] The Tories under Bonar Law made these removals a condition of entering government and, in sacking Haldane, who "made no difficulty," [73] Asquith, committed "the most uncharacteristic fault of (his) whole career".[74] In a letter to Grey, Asquith wrote of Haldane; "He is the oldest personal and political friend that I have in the world and, with him, you and I have stood together for the best part of 30 years."[75] But he was unable to express these sentiments directly to Haldane, who was greatly hurt. Asquith handled the allocation of offices more successfully, appointing Bonar Law to the relatively minor post of Colonial Secretary,[76] taking responsibility for munitions from Kitchener and giving it, as a new ministry, to Lloyd George and placing Balfour at the Admiralty, in place of Churchill, who was demoted to the sinecure Cabinet post of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Overall the Liberals held 12 Cabinet seats, including most of the important ones, while the Tories held 8.[77] Despite this outcome, many Liberals were dismayed, the sacked Charles Hobhouse writing; "The disintegration of the Liberal Party is complete. Ll.G. and his Tory friends will soon get rid of Asquith."[78] From a party, and a personal, perspective, the creation of the First Coalition was seen as a "notable victory for (Asquith), if not for the allied cause".[72] But Asquith's dismissive handling of Bonar Law also contributed to his own and his party's later destruction.[79]

War re-organisation

[edit]Having reconstructed his government, Asquith attempted a re-configuration of his war-making apparatus. The most important element of this was the establishment of the Ministry of Munitions,[80] followed by the re-ordering of the War Council into a Dardanelles Committee, with Maurice Hankey as secretary and with a remit to consider all questions of war strategy.[81] But criticism of Asquith's style continued. The Earl of Crawford, who had joined the Government as Minister of Agriculture, described his first Cabinet meeting; "It was a huge gathering, so big that it is hopeless for more than one or two to express opinions on each detail[...] Asquith somnolent – hands shaky and cheeks pendulous. He exercised little control over debate, seemed rather bored, but good humoured throughout." Lloyd George was less tolerant, Lord Riddell recording in his diary; "(He) says the P.M. should lead not follow and (Asquith) never moves until he is forced, and then it is usually too late."[82] And crises, as well as criticism, continued to assail the Prime Minister, "envenomed by intra-party as well as inter-party rancour".[83]

Conscription

[edit]

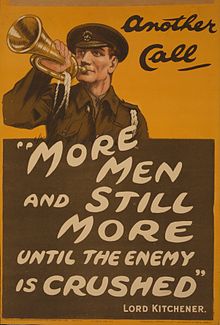

The insatiable demand for manpower for the Western Front had been foreseen early on. A volunteer system had been introduced at the outbreak of war, and Asquith was reluctant to change it for political reasons, as many Liberals, and almost all of their Irish Nationalist and Labour allies, were strongly opposed to conscription.[84] Volunteer numbers dropped,[85] not meeting the demands for more troops for Gallipoli, and much more strongly, for the Western Front.[86] This made the voluntary system increasingly untenable; Asquith's daughter Violet wrote in March 1915; "Gradually every man with the average number of limbs and faculties is being sucked out to the war."[87] In July 1915, the National Registration Act was passed, requiring compulsory registration for all men between the ages of 18 and 65.[88] This was seen by many as the prelude to conscription but the appointment of Lord Derby as Director-General of Recruiting instead saw an attempt to rejuvenate the voluntary system, the Derby Scheme.[89] Asquith's slow steps towards conscription continued to infuriate his opponents, Sir Henry Wilson writing to Leo Amery; "What is going to be the result of these debates? Will 'wait and see' win, or can that part of the Cabinet that is in earnest and is honest force that damned old Squiff into action?"[90] The Prime Minister's balancing act, within Parliament and within his own party, was not assisted by a strident campaign against conscription conducted by his wife. Describing herself as "passionately against it",[91] Margot Asquith engaged in one of her frequent influencing drives, by letters and through conversations, which had little impact other than doing "great harm" to Asquith's reputation and position.[92]

By the end of 1915, it was clear that conscription was essential and Asquith laid the Military Service Act in the House of Commons on 5 January 1916.[93] The Act introduced conscription of single men, and was extended to married men later in the year. Asquith's main opposition came from within his own party, particularly from Sir John Simon, who resigned. Asquith described Simon's stance in a letter to Sylvia Henley; "I felt really like a man who had been struck publicly in the face by his son."[94] Some years later, Simon acknowledged his error; "I have long since realised that my opposition was a mistake."[95] Asquith's achievement in bringing the bill through without breaking up the government was considerable, his wife writing; "Henry's patience and skill in keeping Labour in this amazing change in England have stunned everyone,"[96] but the long struggle "hurt his own reputation and the unity of his party".[97]

Ireland

[edit]On Easter Monday 1916, a group of Irish Volunteers and members of the Irish Citizen Army seized a number of key buildings and locations in Dublin and elsewhere. There was heavy fighting over the next week before the Volunteers were forced to surrender.[98] Distracted by conscription, Asquith and the Government were slow to appreciate the developing danger, [99] which was exacerbated when, after hasty courts martial, a number of the Irish leaders were executed. On 11 May Asquith crossed to Dublin and, after a week of investigation, decided that the island's governance system was irredeemably broken,[100] He turned to Lloyd George for a solution. With his customary energy, Lloyd George brokered a settlement which would have seen Home Rule introduced at the end of the War, with the exclusion of Ulster.[101] However, neither he, nor Asquith, appreciated the extent of Tory opposition, the plan was strongly attacked in the House of Lords, and was abandoned thereafter.[102] The episode damaged Lloyd George's reputation, but also that of Asquith, Walter Long speaking of the latter as; "terribly lacking in decision".[103] It also further widened the divide between Asquith and Lloyd George, and encouraged the latter in his plans for government reconstruction; "Mr. A gets very few cheers nowadays."[104]

Progress of the war

[edit]

Fall: November–December 1916

[edit]The events that led to the collapse of the First Coalition were exhaustively chronicled by almost all of the major participants,[105] (although Asquith himself was a notable exception), and have been minutely studied by historians in the 100 years since.[106] Although many of the accounts and studies differ in detail, and present a somewhat confusing picture overall, the outline is clear. As Adams wrote; "The Prime Minister depended upon [a] majority [in] Parliament. The faith of that majority in Asquith's leadership had been shaken and the appearance of a logical alternative destroyed him."[107]

Nigeria debate and Lord Lansdowne's memorandum

[edit]

The touch paper for the final crisis was the unlikely subject of the sale of captured German assets in Nigeria.[108] As Colonial Secretary, the Conservative leader Bonar Law led the debate and was subject to a furious attack by Sir Edward Carson. The issue itself was trivial,[109] but the fact that Law had been attacked by a leading member of his own party, and was not supported by Lloyd George (who absented himself from the House only to dine with Carson later in the evening), was not.[110] Margot Asquith immediately sensed the coming danger; "From that night it was quite clear that Northcliffe, Rothermere, Bonar, Carson, Ll.G (and a man called Max Aitken) were going to run the Government. I knew it was the end."[111] Grey was similarly prescient, writing; "Lloyd George means to break up the Government."[112] Bonar Law saw the debate as a threat to his own political position,[113] as well as another instance of lack of grip by the government.[114] The situation was further inflamed by the publication of a memorandum on future prospects in the war by Lord Lansdowne.[115] Circulated on 13 November, it considered, and did not dismiss, the possibility of a negotiated settlement with the Central Powers. Asquith's critics immediately assumed that the memorandum represented his own views and that Lansdowne was being used a stalking horse,[116] Lord Crewe going so far as to suggest that the Lansdowne Memorandum was the "veritable causa causans[a] of the final break-up".[117]

Triumvirate gathers

[edit]On 20 November 1916 Lloyd George, Carson and Bonar Law met at the Hyde Park Hotel.[118] The meeting was organised by Max Aitken who was to play central roles both in the forthcoming crisis and in its subsequent historiography.[119] Max Aitken was a Canadian adventurer, millionaire, and close friend of Bonar Law.[120] His book on the fall of the First Coalition, Politicians and the War 1914–1916, although always partial and sometimes inaccurate, gives a detailed insider's view of the events leading up to Asquith's political demise.[121] The trio agreed on the necessity of overhauling the government and further agreed on the mechanism for doing so; the establishment of a small War Council, chaired by Lloyd George, with no more than five members and with full executive authority for the conduct of the war.[122] Asquith was to be retained as prime minister, and given honorific oversight of the War Council, but day to day operations would be directed by Lloyd George.[118] This scheme, although often reworked, remained the basis of all proposals to reform the government until Asquith's fall on 6 December. Until almost the end, both Bonar Law,[123] and Lloyd George,[124] wished to retain Asquith as premier. But Aitken,[121] Carson[125] and Lord Northcliffe emphatically did not.[126]

Power without responsibility

[edit]

Lord Northcliffe's role was critical, as was the use Lloyd George made of him, and of the press in general. Northcliffe's involvement also highlights the limitations of both Aitken's and Lloyd George's accounts of Asquith's fall. Both minimised Northcliffe's part in the events. In his War Memoirs, Lloyd George stated emphatically; "Lord Northcliffe was never, at any stage, brought into our consultations."[127] Aitken supported this; "Lord Northcliffe was not in active co-operation with Lloyd George."[128] But these claims are contradicted by others. In their biography of Northcliffe, Pound and Harmsworth record Northcliffe's brother Rothermere writing contemporaneously; "Alfred has been actively at work with Ll.G. with a view to bringing about a change."[129] Riddell recorded is his diary for 27 May 1916; "LG never mentions directly that he sees Northcliffe but I am sure they are in daily contact."[130] Margot Asquith was also certain of Northcliffe's role, and of Lloyd George's involvement, although she obscured both of their names when writing in her diary; "I only hope the man responsible for giving information to Lord N- will be heavily punished: God may forgive him; I never can."[131]They are also contradicted by events; Northcliffe met with Lloyd George on each of the three days just prior to Lloyd George's resignation, on 1, 2 and 3 December,[132] including two meetings on 1 December, both before and after Lloyd George put his revised proposals for the War Council to Asquith.[133] It seems improbable that ongoing events were not discussed and that the two men confined their conversations to negotiating article circulation rights for Lloyd George once he had resigned, as Pound and Harmsworth weakly suggest.[134] The attempts made by others to use Northcliffe and the wider press also merit consideration. In this regard, some senior military officers were extremely active; Robertson, for example, writing to Northcliffe in October 1916; "The Boche gives me no trouble compared with what I meet in London. So any help you can give me will be of Imperial value."[135] Lastly, the actions of Northcliffe's newspapers must be considered – in particular The Times editorial on 4 December which led Asquith to reject Lloyd George's final War Council proposals.[136] Thompson, Northcliffe's most recent biographer, concludes; "From the evidence, it appears that Northcliffe and his newspapers should be given more credit than they have generally received for the demise of the Asquith government in December 1916."[137]

To-ing and fro-ing

[edit]Bonar Law met again with Carson and Lloyd George on 25 November and, with Aitken's help, drafted a memorandum for Asquith's signature.[138] This would see a "Civilian General Staff", with Lloyd George as chairman and Asquith as president, attending irregularly but with the right of referral to Cabinet as desired.[138] This, Bonar Law presented to Asquith, who committed to reply on Monday the following week.[139] His reply was an outright rejection; the proposal was impossible "without fatally impairing the confidence of colleagues, and undermining my own authority."[139] Law took Asquith's response to Carson and Lloyd George at Law's office in the Colonial Office. All were uncertain of the next steps.[140] Bonar Law decided it would be appropriate to meet with his senior Conservative colleagues, something he had not previously done.[141] He saw Austen Chamberlain, Lord Curzon and Lord Robert Cecil on Thursday 30 November. All were united in opposition to Lloyd George's War Council plans, Chamberlain writing; "(we) were unanimously of opinion (sic) that (the plans) were open to grave objection and made certain alternative proposals."[142] Lloyd George had also been reflecting on the substance of the scheme and, on Friday 1 December, he met with Asquith to put forward an alternative. This would see a War Council of three, the two Service ministers and a third without portfolio. One of the three, presumably Lloyd George although this was not explicit, would be chairman. Asquith, as Prime Minister, would retain "supreme control."[143] Asquith's reply the same day did not constitute an outright rejection, but he did demand that he retain the chairmanship of the council.[144] As such, it was unacceptable to Lloyd George and he wrote to Bonar Law the next day (Saturday 2 December); "I enclose copy of P.M.'s letter. The life of the country depends on resolute action by you now."[145]

Last four days: Sunday 3 December to Wednesday 6 December

[edit]Sunday 3 December

[edit]Sunday 3 December saw the Conservative leadership meet at Bonar Law's house, Pembroke Lodge.[146] They gathered against a backdrop of ever-growing press involvement, in part fermented by Max Aitken.[147] That morning's Reynold's News, owned and edited by Lloyd George's close associate Henry Dalziel, had published an article setting out Lloyd George's demands to Asquith and claiming that he intended to resign and take his case to the country if they were not met.[148] At Law's house, the Conservatives present drew up a resolution which they demanded Law present to Asquith.[149] This document, subsequently the source of much debate, stated that "the Government cannot continue as it is; the Prime Minister (should) tender the resignation of the Government" and, if Asquith was unwilling to do that, the Conservative members of the Government would "tender (their) resignations."[150] The meaning of this resolution is unclear, and even those who contributed to it took away differing interpretations.[151] Chamberlain felt that it left open the option of either Asquith or Lloyd George as premier, dependent on who could gain greater support. Curzon, in a letter of that day to Lansdowne, stated no one at the Pembroke Lodge meeting felt that the war could be won under Asquith's continued leadership and that the issue for the Liberal politicians to resolve was whether Asquith remained in a Lloyd George administration in a subordinate role, or left the government altogether.[152] Max Aitken's claim that the resolution's purpose was to ensure that "Lloyd George should go"[153] is not supported by most of the contemporary accounts,[154] or by the assessments of most subsequent historians. As one example, Gilmour, Curzon's biographer, writes that the Unionist ministers; "did not, as Beaverbrook alleged, decide to resign themselves in order to strengthen the Prime Minister's hand against Lloyd George..(their intentions) were completely different."[155] Similarly, Adams, Bonar Law's latest biographer, describes Aitken's interpretation of the resolution as "convincingly overturned."[156] Ramsden is equally clear; "the Unionist ministers acted to strengthen Lloyd George's hand, from a conviction that only greater power for Lloyd George could put enough drive into the war effort."[157]

Bonar Law then took the resolution to Asquith, who had, unusually, broken his weekend at Walmer Castle to return to Downing Street.[158] At their meeting, Bonar Law sought to convey the content of his colleagues' earlier discussion but failed to produce the resolution itself.[159] That it was never actually shown to Asquith is incontrovertible, and Asquith confirmed this in his writings.[160] Bonar Law's motives in not handing it over are more controversial. Law himself maintained he simply forgot.[161] Jenkins charges him with bad faith, or neglect of duty.[162] Adams suggests Law's motives were more complex – the resolution also contained a clause condemning the involvement of the press – prompted by the Reynold's News story of that morning[163] – and that, in continuing to seek an accommodation between Asquith and Lloyd George, Law felt it prudent not to share the actual text.[164]

The outcome of the interview between Law and Asquith was clear, even if Law had not been.[165] Asquith immediately decided that an accommodation with Lloyd George, and a substantial reconstruction to placate the Unionist ministers, were required.[166] He summoned Lloyd George and together they agreed a compromise that was, in fact, little different to Lloyd George's 1 December proposals.[167] The only substantial amendment was that Asquith would have daily oversight of the War Council's work and a right of veto.[167] Grigg sees this compromise as "very favourable to Asquith."[168] Cassar is less certain; "The new formula left him in a much weaker position[, his] authority merely on paper for he was unlikely to exercise his veto lest it bring on the collective resignation of the War Council."[169] Nevertheless, both Asquith, Lloyd George, and Bonar Law who had rejoined them at 5.00 p.m., felt a basis for a compromise had been reached and they agreed that Asquith would issue a bulletin that evening announcing the reconstruction of the Government.[169] Crewe, who joined Asquith at Montagu's house at 10.00 p.m. recorded; "accommodation with Mr. Lloyd George would ultimately be achieved, without sacrifice of (Asquith's) position as chief of the War Committee; a large measure of reconstruction would satisfy the Unionist Ministers."[170]

Despite Lloyd George's denials of collaboration, the diary for 3 December by Northcliffe's factotum Tom Clarke, records that; "The Chief returned to town and at 7.00 o'clock he was at the War Office with Lloyd George."[171] Meanwhile Duff Cooper was invited to dinner at Montagu's Queen Anne's Gate house, he afterwards played bridge with Asquith, Venetia Montagu and Churchill's sister-in-law "Goonie", recording in his diary : "..the P.M. more drunk than I have ever seen him, (..) so drunk that one felt uncomfortable ... an extraordinary scene."[172]

Monday 4 December

[edit]The bulletin was published on the morning of Monday 4 December. It was accompanied by an avalanche of press criticism, all of it intensely hostile to Asquith.[173] The worst was a leader in Northcliffe's Times.[174] This had full details of the compromise reached the day before, including the names of those suggested as members of the War Council. More damagingly still, it ridiculed Asquith, claimed he had conspired in his own humiliation and would henceforth be "Prime Minister in name only."[173] Lloyd George's involvement is uncertain; he denied any,[175] but Asquith was certain he was the source.[176] The author was certainly the editor, Geoffrey Dawson, with some assistance from Carson. But it seems likely that Carson's source was Lloyd George.[132]

The leak prompted an immediate reaction from Asquith; "Unless the impression is at once corrected that I am being relegated to the position of an irresponsible spectator of the War, I cannot possibly go on."[175] Lloyd George's reply was prompt and conciliatory; "I cannot restrain nor I fear influence Northcliffe. I fully accept in letter and in spirit your summary of the suggested arrangement – subject of course to personnel."[177] But Asquith's mind was already turning to rejection of the Sunday compromise and outright confrontation with Lloyd George.[178]

It is unclear exactly whom Asquith spoke with on 4 December. Beaverbrook and Crewe state he met Chamberlain, Curzon and Cecil.[179][180] Cassar follows these opinions, to a degree.[181] But Chamberlain himself was adamant that he and his colleagues met Asquith only once during the crisis and that was on the following day, Tuesday 5 December. Chamberlain wrote at the time "On Tuesday afternoon the Prime Minister sent for Curzon, Bob Cecil and myself. This is the first and only time the three of us met Asquith during those fateful days."[182] His recollection is supported by details of their meetings with Bonar Law and other colleagues,[182] in the afternoon, and then in the evening of the 4th,[183] and by most modern historians, e.g. Gilmour[184] and Adams.[185] Crawford records how little he and his senior Unionist colleagues were involved in the key discussions, and by implication, how much better informed were the press lords, writing in his diary; "We were all in such doubt as to what had actually occurred, and we sent out for an evening paper to see if there was any news!"[186] Asquith certainly did meet his senior Liberal colleagues on the evening of 4 December, who were unanimously opposed to compromise with Lloyd George and who supported Asquith's growing determination to fight.[178] His way forward had been cleared by his tendering the resignation of his government to the King earlier in the day.[181] Asquith also saw Bonar Law who confirmed that he would resign if Asquith failed to implement the War Council agreement as discussed only the day before.[187] In the evening, and having declined two requests for meetings, Asquith threw down the gauntlet to Lloyd George by rejecting the War Council proposal.[188]

Tuesday 5 December

[edit]

Lloyd George accepted the challenge by return of post, writing; "As all delay is fatal in war, I place my office without further parley at your disposal."[188] Asquith had anticipated this response, but was surprised by a letter from Arthur Balfour, who until that point had been removed from the crisis by illness.[189] On its face, this letter merely offered confirmation that Balfour believed that Lloyd George's scheme for a smaller War Council deserved a chance and that he had no wish to remain at the Admiralty if Lloyd George wished him out. Jenkins argues that Asquith should have recognised it as a shift of allegiance.[189] Asquith discussed the crisis with Lord Crewe and they agreed an early meeting with the Unionist ministers was essential. Without their support, "it would be impossible for Asquith to continue."[190]

Asquith's meeting with Chamberlain, Curzon and Cecil at 3.00 p.m. only highlighted the weakness of his position.[165] They unanimously declined to serve in a Government that did not include Bonar Law and Lloyd George,[191] as a Government so constituted offered no "prospect of stability." Their reply to Asquith's follow-up question as to whether they were serve under Lloyd George caused him even more concern. The "Three Cs" stated they would serve under Lloyd George if he could create the stable Government they considered essential for the effective prosecution of the War.[192] The end was near and a further letter from Balfour declining to reconsider his earlier decision brought it about. The Home Secretary, Herbert Samuel, recorded in a contemporaneous note; "We were all strongly of opinion, from which [Asquith] did not dissent, that there was no alternative [to resignation]. We could not carry on without LlG and the Unionists and ought not to give the appearance of wishing to do so."[193] At 7.00 p.m., having been Prime Minister for eight years and 241 days, Asquith went to Buckingham Palace and tendered his resignation.[194] Describing the event to a friend sometime later, Asquith wrote; "When I fully realised what a position had been created, I saw that I could not go on without dishonour or impotence, or both."[195] That evening, he dined at Downing Street with family and friends, his daughter-in-law Cynthia describing the scene; "I sat next to the P.M. – he was too darling – rubicund, serene, puffing a guinea cigar and talking of going to Honolulu."[196] Cynthia believed that he would be back "in the saddle" within a fortnight with his position strengthened.[197]

Later that evening Bonar Law, who had been to the Palace to receive the King's commission, arrived to enquire whether Asquith would serve under him. Lord Crewe described Asquith's reply as "altogether discouraging, if not definitely in the negative."[194][b]

Wednesday 6 December

[edit]I am personally very sorry for poor old Squiff. He has had a hard time and even when 'exhilarated' seems to have had more capacity and brain power than any of the others. However, I expect more action and less talk is needed now

General Douglas Haig on Asquith's fall (6 December)[199]

Wednesday saw an afternoon conference at Buckingham Palace, hosted by the King and chaired by Balfour.[200] There is some doubt as to the originator of the idea,[200] although Adams considers that it was Bonar Law.[201] This is supported by a handwritten note of Aitken's, reproduced in A.J.P. Taylor's life of that politician, which reads: "6th Wed. Meeting at BL house with G. (Lloyd George) and C. (Carson) – Decide on Palace Conference."[202] Conversely, Crewe suggests that the suggestion came jointly from Lord Derby and Edwin Montagu.[203] However it came about, it did not bring the compromise the King sought. Within two hours of its breakup, Asquith, after consulting his Liberal colleagues,[204] except for Lloyd George, declined to serve under Bonar Law,[201] who accordingly declined the King's commission.[205] At 7.00 p.m. Lloyd George was invited to form a Government. In just over twenty four hours he had done so, forming a small War Cabinet instead of the mooted War Council, and at 7.30 p.m. on Thursday 7 December he kissed hands as Prime Minister.[206] His achievement in creating a government was considerable, given that almost all of the senior Liberals sided with Asquith.[207] Balfour's acceptance of the Foreign Office made it possible.[208] Others placed a greater responsibility on Asquith as the author of his own downfall, Churchill writing; "A fierce, resolute Asquith, fighting with all his powers would have conquered easily. But the whole trouble arose from the fact that there was no fierce resolute Asquith to win this war or any other."[209]

The Asquiths finally vacated 10 Downing Street on 9 December. Asquith, not normally given to displays of emotion, confided to his wife that he felt he had been stabbed.[210] He likened himself (10 December) to the Biblical character Job, although he also commented that Aristide Briand's government was also under strain in France.[211] Lord Newton wrote in his diary of meeting Asquith at dinner a few days after the fall; "It became painfully evident that he was suffering from an incipient nervous breakdown and before leaving the poor man completely collapsed."[212] Asquith was particularly appalled at Balfour's behaviour,[213] especially as he had argued against Lloyd George to retain Balfour at the Admiralty.[214] Writing years later, Margot's spleen was still evident; "between you and me, this is what hurt my husband more than anything else. That Lloyd George (a Welshman!) should betray him, he dimly did understand, but that Arthur should join his enemy and help to ruin him, he never understood."[214]

Asquith's fall was met with rejoicing in much of the British and Allied press and sterling rallied against the German mark on the New York markets. Press attacks on Asquith continued and indeed increased after the publication of the Dardanelles Report.[215]

Wartime Opposition Leader

[edit]ADD David French Strategy of the Lloyd George Coalition Grey later paid tribute to Asquith’s willingness to give credit to successful ministers and to take responsibility himself for things that went wrong. [216] Asquith soon came to be regarded as the “Last of the Romans”. [217]

Asquith supported the government candidate at a by-election in the spring of 1917. At his insistence, Liberal activity in the constituencies was largely at a standstill anyway. He did not protest when overseas sale of “The Nation” was banned and abstained on the Corn Production Bill. In the Commons he welcomed US entry into the war in April 1917 and endorsed female suffrage. After urging by C.P.Scott Lloyd George sought his advice about Ireland in May 1917, but thought him “perfectly sterile”. [218] In May 1917 he was offered the post of Lord Chancellor, which carried a 10k salary and a 5k pension, but refused after consulting Crewe. Asquith was a supporter of the idea of the League of Nations and of proportional representation.[219] Asquith toured the Western Front at Haig’s invitation in Sep 1917. [218] In September 1917 there was initial War Cabinet disagreement at how to respond to the peace feelers from German Foreign Minister von Kuhlmann. Asquith spoke at Leeds to the National War Aims Committee, urging that Germany must return Alsace-Lorraine to France but also that the Allies must not permit Germany to make gains at the expense of the Russian Republic. Asquith had been briefed by Eric Drummond, a senior foreign office official, as Lloyd George was thought to be toying with the latter option. (but only if generals said Allies couldn’t win). [220] He spoke at Liverpool in October 1917. [219][218] Late in 1917 Lloyd George moved to set up an inter-Allied Supreme War Council to reassert political control over strategy, contrary to the wishes of the British generals, who still enjoyed a great deal of press support. After Lloyd George's Paris speech (12 November) in which he scoffed at the Allies' Western Front "victories" and said that "when he saw the appalling casualty lists he wish(ed) it had not been necessary to win so many of them," Asquith (briefed by Robertson) rose to loud cheers to debate the matter in the Commons (19 November), amid talk of Austen Chamberlain withdrawing support from the government. Lloyd George survived by claiming that the aim of the Supreme War Council was purely to "coordinate" policy. [221] [222] Asquith’s speech on the Supreme War Council on 19 November, at which he argued that the general’s control of strategy should not be interfered with, was lacklustre. The Northcliffe Press outside, and Carson inside the Commons, backed Lloyd George with some reluctance because of his determination to win the war. [223] Asquith was urged by some Liberal MPs, including frontbenchers, to back Lansdowne, after his call for a negotiated peace in his Letter of 29 November. But in a speech at Birmingham on 11 December he gave only a cautious welcome to the Lansdowne Letter but urged that the war continue until Germany had been made to disgorge her conquests, although unlike Lloyd George three days later he did not advocate (REPHRASE) democracy in Germany.[224][225] [219] Lloyd George and Asquith (and Edward Grey, who had been persuaded with some reluctance to attend) breakfasted together on 5 January 1918. The meeting had been arranged by Lord Buckmaster and C.P.Scott who were keen to promote Liberal reunion. They discussed Lloyd George’s upcoming Caxton Hall speech to the TUC outlining British War Aims. Margot claimed that Asquith, along with Smuts and Lord Robert Cecil, had had far more input into them than Lloyd George was willing to admit in public. [226] By 13 Feb 1918 Haldane recorded that Margot was actively intriguing with H A Gwynne for a political combination of Asquith and Lansdowne, a combination of which Haldane “in the main deplore(d)” [227] Asquith was also active in Parliament when Lloyd George, keen to refocus British efforts against Turkey rather than on the Western Front, removed Robertson as CIGS early in 1918. In a House of Commons made angry by the press war between allies of Lloyd George and the generals, Asquith (12 February) was greeted with cheers for two minutes. Lloyd George ended the debate by challenging the House of Commons to bring down the government; the unappealing thought of Asquith returning as prime minister was one of the factors in his surviving the crisis. [228] [229] Asquith did not do much about the removal of Robertson, although he would have had the support of HA Gwynne. [230] Asquith also played little active part in the debate on Irish Conscription in early 1918. [218] 1 May Henry Wilson recorded that Asquith was under much pressure to attack Lloyd George. [230] Maurice wrote to Asquith on 6 May 1918, forewarning him but saying that he had decided not to consult him. [231] 9 May Asquith moved for a Select Committee. Trevor Wilson described his contribution to the debate as “innocuous”; Asquith denied any hostility to Lloyd George or even acceptance of Maurice’s charges. 10 May editor of Manchester Guardian wrote to a friend that Asquith was “discredited”. Koss believes that Asquith wanted to damage Lloyd George, but not to force a general election which the Liberals would very likely lose. [230] Around this time Pemberton Billing made his scurrilous accusations (in “The Vigilante”) that the Asquiths were among the 47,000 public figures corrupted by German agents with sexual favours. Reading visited him on 28 May 1918 to offer him any post in government except Prime Minister. Asquith took the unusual step of writing a memorandum stating that he did not trust Lloyd George enough to serve under him. [232] He spoke at Manchester in September 1918, where he spoke at a large audience with an overflow, and called for a “clean peace”.[219][218] On 8 October 1918 Asquith met with Lansdowne, Grey, Reading and Gilbert Murray about the Peace Talks. [233] In late October further overtures were made to Asquith to join the government as Lord Chancellor. Asquith apparently said that he also distrusted Balfour enough to not want to serve with him. Koss argues that now that the war was clearly almost won Asquith no longer had any reason for not criticising Lloyd George, and was passing off pique as principle. [232]

New Material to be worked in

[edit]Course of the War

[edit]Continued Allied failure and heavy losses at the Battle of Loos between September and October 1915 ended any remaining confidence in the British commander, Sir John French and in the judgement of Lord Kitchener.[234] Asquith resorted to a favoured stratagem and, persuading Kitchener to undertake a tour of the Gallipoli battlefield in the hope that he could be persuaded to remain in the Mediterranean as Commander-in-Chief,[235] took temporary charge of the War Office himself.[236] He then replaced French with Sir Douglas Haig; the latter recording in his diary for 10 December 1915; "About 7 pm I received a letter from the Prime Minister marked 'Secret' and enclosed in three envelopes. It ran 'Sir J. French has placed in my hands his resignation ... Subject to the King's approval, I have the pleasure of proposing to you that you should be his successor.'"[237] Asquith also appointed Sir William Robertson as Chief of the Imperial General Staff with increased powers, reporting directly to the Cabinet and with the sole right to give them military advice, relegating the Secretary of State for War to the tasks of recruiting and supplying the army.[238] Lastly, he instituted a smaller Dardanelles Committee, re-christened the War Committee,[239] with himself, Balfour, Bonar Law, Lloyd George and Reginald McKenna as members[240] although, as this soon increased, the Committee continued the failings of its predecessor, being "too large and lack(ing) executive authority".[241] None of this saved the Dardanelles Campaign and the decision to evacuate was taken in December,[242] resulting in the resignation from the Duchy of Lancaster of Churchill,[243] who wrote, "I could not accept a position of general responsibility for war policy without any effective share in its guidance and control."[240] Further reverses took place in the Balkans: the Central Powers overran Serbia, forcing the Allied troops which had attempted to intervene back towards Salonika.[244]

Early 1916 saw the start of the German offensive at Verdun, the "greatest battle of attrition in history".[245] In late May, the only significant Anglo-German naval engagement of the War took place at The Battle of Jutland. Although a strategic success,[246] the greater loss of ships on the Allied side brought early dismay.[247] Lord Newton, Paymaster General and Parliamentary spokesman for the War office in Kitchener's absence, recorded in his diary; "Stupefying news of naval battle off Jutland. Whilst listening to the list of ships lost, I thought it the worst disaster that we had ever suffered."[248] This despondency was compounded, for the nation, if not for his colleagues, when Lord Kitchener was killed in the sinking of HMS Hampshire on 5 June.[249]

Asquith first considered taking the vacant War Office himself but then offered it to Bonar Law, who declined it in favour of Lloyd George.[250] This was an important sign of growing unity of action between the two men and it filled Margot Asquith with foreboding; "I look upon this as the greatest political blunder of Henry's lifetime, ... We are out: it can only be a question of time now when we shall have to leave Downing Street."[251][252]

Asquith followed this by agreeing to hold Commissions of Inquiry into the conduct of the Dardanelles and of the Mesopotamian campaign, where Allied forces had been forced to surrender at Kut.[253] Sir Maurice Hankey, Secretary to the War Committee, considered that; "the Coalition never recovered. For (its) last five months, the function of the Supreme Command was carried out under the shadow of these inquests."[254] But these mistakes were overshadowed by the limited progress and immense casualties of the Battle of the Somme, which began on 1 July 1916, and then by another devastating personal loss, the death of Asquith's son Raymond, on 15 September at the Battle of Flers–Courcelette.[255] Asquith's relationship with his eldest son had not been easy. Raymond wrote to his wife in early 1916; "If Margot talks any more bosh to you about the inhumanity of her stepchildren you can stop her mouth by telling her that during my 10 months exile here the P.M. has never written me a line of any description."[256] But Raymond's death was shattering, Violet writing; "...to see Father suffering so wrings one",[257] and Asquith passed much of the following months "withdrawn and difficult to approach".[258] The War brought no respite, Churchill writing that; "The failure to break the German line in the Somme, the recovery of the Germanic powers in the East [i.e. the defeat of the Brusilov Offensive], the ruin of Roumania and the beginnings of renewed submarine warfare strengthened and stimulated all those forces which insisted upon still greater vigour in the conduct of affairs."[259]

Launch Pad

[edit]Bonar Law

[edit]A party truce was provisionally agreed between Asquith and Bonar Law on 30 July.[19]

Bonar Law sent a letter to Asquith on behalf of the Conservatives on 2 August offering full support if the government backed France and Russia. Asquith replied that the government was under no obligation, real or implied, to help them.[26]

On Monday 3 August, the day of Grey’s hour-long speech to the House of Commons, Bonar Law visited Asquith to express his concerns that the war or the party truce might be an excuse for “jiggery pokery” over Home Rule and Welsh Disestablishment.[31]

Bonar Law’s motives were partly a sense of patriotic duty and party a sense of partisan advantage, that it was better to let an Asquith Government take the difficult decisions whilst trying to maintain the support of Labour and the Irish Nationalists. Chamberlain, Long, Lansdowne, Curzon and Derby were all unenthusiastic. [260] Bonar Law may have accepted the Colonies rather than the Exchequer or Munitions because of the criminal prosecution pending against William Jacks & Company, in which his brother John Law was still a partner. Two other partners were eventually found guilty and imprisoned. [261]

Kitchener

[edit]Long

[edit]Walter Long asked for the Home Office in May 1915 but was appointed President of the Local Government Board.[261]

Simon

[edit]Simon declined the Woolsack in May 1915, saying that he preferred “the sack rather than the woolsack”. [81][262]

Lloyd George

[edit]Roy Jenkins writes "Lloyd George was a principal participant in most quarrels at this time". Bonar Law commented that Lloyd George was both the Prime Minister's right hand man and Leader of the Opposition. On 12 October 1916 Lloyd George spoke in support of Carson's demand that more men be provided for the Army, although it was unclear where they were to come from without stripping men from industry or extending conscription to Ireland.[263]

Venetia

[edit]Asquith was writing an average of a letter a day to Miss Stanley, 26 in August 1914, often of 500-1000 words. Between January and March 1915 he wrote her 141 letters and 4 in one day on 30 March, 3,000 words in total. Venetia was in London to train as a nurse at Whitechapel, and he often went for a drive with her on Friday afternoons.[264]

On 22 April 1915 he wrote to Venetia “You will tell me, won’t you, the real truth at once?” He was also upset at Rupert Brooke’s death at Lemnos. Early in May 1915 he stayed with Venetia and her family, and for the first time worried that he bored her. Venetia was due to start as a nurse at Wimereux Military Hospital on 10 May but was struck down by fever. Asquith visited her for ten minutes then walked back to Downing Street with Montagu who had also been there. On Tuesday 11 May he wrote her two letters and called to see her, but was not allowed to see her. On Wednesday 12 May she wrote to tell him that she was engaged to Montagu, whose proposal she had rejected with horror two years earlier. She converted to Judaism so he could keep his fortune. Venetia married on 24 July, and any letters from Asquith to her after that were in reply to initiatives on her part. Venetia was, in Jenkins’ view, probably a bit crushed by the intensity of his feelings. [265]

1914-15

[edit]The party truce was formally confirmed on 28 August. Liberals, Conservatives and Labour agreed not to fight one another at by-elections in Britain (Ireland was not included). Bonar Law, many of his MPs fighting in the forces, was sure that the next general election would see a Conservative majority, but wished to see the Liberals carry responsibility for the war effort until then.[19]

5 August Kitchener War Secretary.[35]

Asquith was impressed by Kitchener’s contempt for public opinion. As early as Cabinet on 26 August, Churchill ranted on about the need for conscription (Lord Emmott thought him “both stupid and boring” and observed that Asquith was “contemptuous”), but Asquith, who pointed out that that the Liberal Party would be divided on the issue, was able to leave Kitchener to deal with the matter on the grounds that he did not yet have enough equipment for those who had volunteered.[266]

Much Liberal opinion saw the war as a betrayal of Liberal principles, and came increasingly to resent the greater state control made necessary by the war effort, and to advocate democracy in Germany and (Britain’s ally) Russia, as well as open diplomacy and a clampdown on armaments companies; the latter two would be important political issues in the postwar period.[267]

Asquith privately sympathised with radical criticism of state control, but saw his juggling act between radicals and Conservatives not just as a matter of political tactics but of a duty to maintain national unity. He also took an interest in longer-term postwar plans for which the credit was taken by others. He delighted in Lady Tree’s witticism “Do you take an interest in the war?”[268]

Tory opinion still suspicious after “Bloody Week” in Ulster. Worse after Irish Home Rule and Welsh Disestablishment (over the protests of the Archbishop of Canterbury) were put onto the statute book on 15 September, contrary to assurances which had supposedly been given during the party truce. Bonar Law accused Asquith of deception, and led his followers out of the Chamber in protest. Asquith jeered at them as “not really a very impressive spectacle, a lot of middle-aged and for the most part middle-aged gentlemen trying to look like early French revolutionaries in the Tennis Court (LINK)” He wrote to Venetia that “Bonar Law never sank so low in his gutter as today” and that McKenna had had to go upstairs and lie down lest he be tempted to attack him. Redmond scoffed at Bonar Law attacking the integrity of the government whilst saying he wanted to support it. [269]

On 15 September 1914, with the Battle of the Aisne (believed at the time to be a major Allied victory as the Germans were being repulsed from the Marne) in progress, Bonar Law led a mass exodus of Conservative MPs from the Commons. “Bonar Law never sank so low in his gutter as today”.[270]

In late September and early October 1914 Asquith spoke at London, Edinburgh, Cardiff and Dublin, which apart from Newcastle in April 1915 were his only public speeches in the first nine months of the war. He never visited his constituency of East Fife in this period.[270]

Asquith wrote of Kitchener in October 1914 “K. who generally finds thing out sooner or later – as a rule rather later”.[271]

By the end of October Kitchener had revised his earlier estimate and thought the war would end sooner through ammunition shortage. [272]

War Council set up in late November 1914, not initially a threat to Kitchener.[273]

A War Council was set up in November 1914. It contained Asquith, Churchill, Lloyd George, Kitchener, Grey and Balfour, the only Tory. Haldane joined in January 1915 and Hankey was secretary. By early 1915 the Cabinet was back to one meeting a week.[274]

On 29 December 1914 Churchill wrote to Asquith recommending Fisher’s scheme for landings in the Baltic rather than leaving British armies “to chew barbed wire in Flanders”. On 31 December he proposed an attack on Gallipoli as well as the Baltic, and urged more frequent meetings of the War Council. Lloyd George, who favoured an Allied presence at Salonika and was already critical of Kitchener, also wrote to Asquith on 31 December urging more frequent War Council meetings.[275]

Asquith (5 December 1914) professed himself “altogether opposed” to an attack on the Dardanelles. Lloyd George favoured landings in the Balkans and against the Turks in Syria. At Asquith’s behest Hankey circulated a paper (28 December) advocating an attack on the Dardanelles to seize Constantinople. “Are there not other alternatives than sending our armies to chew barbed wire in Flanders” Churchill had earlier favoured a Dardanelles attack, and wrote to Asquith on 29 December 1914 advocating an assault on Schleswig-Holstein, which would enable Britain to seize the Kiel Canal, take control of the Baltic and help land a Russian army near Berlin.[276]

By the start of 1915 both Asquith and Lloyd George felt there was a need for some kind of victory.[277]

After consulting Hankey, Churchill moved back in favour of an attack on the Dardanelles. The Foreign Office also favoured the scheme as likely to encourage Balkan countries to join the Allies, as did Kitchener, although he was reluctant to release troops. Greek reluctance to allow Allied troops to land at Salonika also helped Britain’s leaders move towards the Dardanelles plan, which was adopted in principle by the War Council on 13 January 1915 – Asquith kept quiet until the end before concurring, adding that it might encourage Italy to join the Allies. Asquith also had to broker an agreement between Churchill and Fisher, who was sceptical of the Dardanelles plan but agreed, to his subsequent regret, to cancel his resignation when Asquith backed Churchill. [276]

The War Council met on 7, 8 and 13 January 1915. Asquith, Sir John French, Balfour, Kitchener, Fisher, Churchill, Sir Arthur Wilson, Crewe, Grey and Lloyd George attended, although as Asquith met Venetia Stanley shortly afterward we do not have a detailed account of what was said. The topic of the intermingling of the Kitchener armies (explain) came up. Asquith was a westerner by inclination, so did not demand any shift in resources away from the BEF and towards amphibious operations.[278]

The original plan was for a purely naval attack on the Dardanelles. Fisher did not want to dissipate the Grand Fleet by sending modern battleships to attack Turkey, and wanted troops used as well.[279]

Fisher was an early bird and Churchill a night owl, so in practice they operated something of a shift system. Fisher and Churchill came to Asquith on 28 January so that he could resolve their differences. They agreed to an attack on the Dardanelles provided Churchill abandoned his plan to bombard Zeebrugge.[280]

Argument raged throughout February as to whether the 29th Division, Britain’s last fresh division of regular troops and which Kitchener was unwilling to release, should be used. Asquith thought that it should, but was unwilling to overrule Kitchener. The naval bombardment began at the end of February 1915, throwing away the advantage of surprise and alerting the Turks to reinforce their positions. Kitchener finally agreed to release the 29th Division on 10 March, but it was not yet in theatre by the time of the next major naval bombardment on 18 March.[281]

Asquith would have preferred a greater commitment of troops, but was unwilling to overrule Kitchener.[282]

Asquith remained “an incomparable technician” who had predicted the course of events and managed his own party beautifully. But wartime showed his placid habits and active social life in a poor light. From the start of 1915 there was criticism, even from some of his own ministers, of his frequent attendance at dinner parties at which government secrets were alleged to be discussed.[283]

Long holidays were now impossible but he often read in the Athenaeum Library in the late afternoon. Venetia was in London to train as a nurse at Whitechapel, and he often went for a drive with her on Friday afternoons, before catching the train out of London to Walmer Castle (Lord Beauchamp was Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports at the time), which was conveniently between London and the front, for the weekend.[264]

In January 1915 he fell to his knees and wept for Percy Illingworth. Grey had to lecture him about need to remove his children’s German governess from Number Ten. Rumours abounded that the Asquith family had German links (financial or romantic) or entertained German prisoners. Margot urged Leo Maxse not to attack Haldane for his supposed German sympathies.[284]

Attacks on Liberal ministers (Harcourt, Haldane) were led by WAS Hewins, Sir Richard Cooper, Lord Charles Beresford, Joynson-Hicks, Ronald McNeill, Jesse Collings – but were quietly condoned by Bonar Law, Carson and Long.[285]

On the death of Percy Ilingworth, Asquith appointed John Gulland (he rejected Donald Maclean as “quite an impossible person”) Chief Whip, announced 25 January 1915. He lacked the skill to supervise activity in the Parliamentary Party and in the constituencies. Asquith himself spent a great deal of time mediating between colleagues.{sfn|Koss|p=176-7}}

Lloyd George and Montagu came back from Paris (9 February 1915) critical of the weakness of the Coalition government (LINK UNION SACREE) there, to Asquith’s delight.[286]

In early February 1915 Asquith was toying with the idea of appointing Churchill Viceroy of India after the war.[287]

From early 1915, Churchill and Horatio Bottomley were already agitating for coalition. Bonar Law and Lansdowne were invited to attend the War Council on 10 February but thought it best not to attend further meetings rather than risk antagonising their own party. [286]

In mid March 1915 Churchill was rumoured to be intriguing to make Balfour, whom he constantly invited to the Admiralty, Foreign Secretary instead of Sir Edward Grey. Asquith wrote of him “I regard his future with many misgivings … He will never get to the top in English politics, with all his wonderful gifts; to speak with the tongue of men and angels, and to spend laborious days and nights in administration, is no good if a man does not inspire trust.”[287]

Bonar Law helped get a Welsh Church measure through on 15 March 1915, although this irritated the Conservative backbenchers even more.[288] In March 1915 the Welsh MPs whom he likened to “moutons enrages … baa’ed and bleated and tossed their crinkled horns as if they were in a gale on one of their native mountainsides.” the Archbishop of Canterbury had stirred them up that afternoon.[270]

On 22 March General Hamilton, newly arrived to take command, persuaded Admiral deRobeck to delay further attacks until the troops were ready, which was not expected to be until 10 April. Fisher stood firm against Churchill’s and Asquith’s urgings that the navy push on more aggressively, even at the cost of losing ships. Amphibious landings were finally launched on the Gallipoli Peninsula, which the Turks had had ample time to reinforce and fortify, on 25 April. At the end of the first week of May 1915 Admiral de Robeck, who wanted more naval attacks, was recalled to London. Churchill was not keen as he wanted to offer some of the Dardanelles fleet to Italy (for use against Austria-Hungary in the Adriatic) as a sweetener for joining the Allies. On 12 May HMS “Queen Elizabeth”, the most modern battleship in the world, was withdrawn because of the risk of U-Boat attacks, to Kitchener’s fury and a virtual admission of failure.[52]

His Newcastle speech in April 1915 was one of his few major public speeches at this period.[270] 20 April 1915 Asquith Newcastle speech on munitions. [273]

On 10 May 1915 Lord Salisbury urged the appointment of a more vigorous Under-Secretary for War (in place of Asquith’s brother-in-law H.J.Tennant) to take some of the strain off Kitchener.[289]