Rubicon (protein)

| RUBCN | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | RUBCN, RUBICON, SCAR15, KIAA0226, RUN and cysteine rich domain containing beclin 1 interacting protein, rubicon autophagy regulator | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

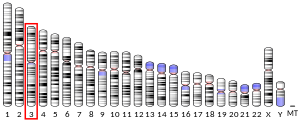

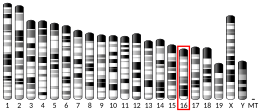

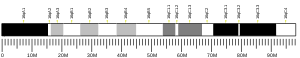

| External IDs | OMIM: 613516; MGI: 1915160; HomoloGene: 15687; GeneCards: RUBCN; OMA:RUBCN - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rubicon (run domain Beclin-1-interacting and cysteine-rich domain-containing protein) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the RUBCN gene.[5][6] Rubicon is one of the few known negative regulators of autophagy, a cellular process that degrades unnecessary or damaged cellular components.[7] Rubicon is recruited to its sites of action through interaction with the small GTPase Rab7,[7][8] and impairs the autophagosome-lysosome fusion step of autophagy through inhibition of PI3KC3-C2 (class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex 2).[7][9]

Negative modulation of Rubicon is associated with reduction of aging and aging-associated diseases: knockout of Rubicon increases lifespan in roundworms and female fruit flies,[10] and in mice decreases kidney fibrosis and α-synuclein accumulation.[10]

In addition to regulation of autophagy, Rubicon has been shown to be required for LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP) and LC3-associated endocytosis (LANDO).[11] Rubicon has also been shown to negatively regulate the innate immune response through direct interaction with multiple downstream regulatory molecules.[12][13][14]

Structure

[edit]

Rubicon consists of 972 amino acids and has an N-terminal RUN domain, a middle region (MR), and a C-terminal Rubicon homology (RH) domain.[15]

The Rubicon homology domain is rich in cysteine residues and binds at least 4 divalent Zinc ions, forming zinc finger motifs.[7] The structural basis for interaction between Rubicon and GTP-bound Rab7 has been experimentally determined (PDB ID: 6WCW).[7][16]

Function

[edit]The function of the N-terminal RUN domain are unknown, but it is required for autophagy suppression.[17] The middle region contains the PI3K-binding domain (PIKBD), which mediates inhibition of PI3KC3-C2.[9] The C-terminal Rubicon homology domain mediates interaction with Rab7, and is shared by other RH domain-containing autophagy regulatory proteins, including PLEKHM1 and Pacer (also known as RUBCNL, Rubicon-like Autophagy Enhancer).[7]

Autophagy-dependent

[edit]Rubicon suppresses autophagy through association with and inhibition of PI3KC3-C2.[18] Specifically, Rubicon directly binds PI3KC3-C2[19][5] and inhibits recruitment of PI3KC3-C2 to the membrane through conformational modulation of the Beclin-1 subunit.[9] This activity prevents PI3KC3-directed generation of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PI3P) at the autophagosome membrane, and a resulting failure to recruit machinery that directs autophagosome-lysosome fusion.[9] Rubicon is targeted to its site of action through direct interaction with Rab7, which decorates late endosomes and late autophagosomes.[7][8]

Autophagy-independent

[edit]Rubicon has been shown to suppress the innate immune response and in some cases exacerbate viral replication.[12] Rubicon suppresses cytokine responses through interaction with NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO),[12] interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3)[14] and caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 9 (CARD9).[13]

Role in aging and disease

[edit]Aging-related diseases

[edit]Rubicon expression levels increase with age in mice and other model organisms, suggesting that Rubicon may cause age-associated decrease of autophagy.[10] Since reduced autophagy is associated with aging and age-related diseases, modulation of Rubicon has been identified as a potential therapeutic target.[7][9]

In mice, Rubicon knockout reduces α-synuclein accumulation in the brain and reduces interstitial fibrosis in the kidney.[10]

Aging

[edit]Rubicon knockout increases lifespan in roundworms (C. elegans) through modulation of autophagy, and also increases lifespan in female fruit flies (D. melanogaster).[10]

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

[edit]Rubicon levels are increased in mouse models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).[20] Knockout of Rubicon in hepatocytes improves liver steatosis and autophagy, suggesting that Rubicon contributes to NAFLD pathogenesis.[20]

Metabolic disease

[edit]Age-dependent decline of Rubicon expression in adipose tissues may exacerbate metabolic disorders due to excessive autophagic activity.[21]

Salih ataxia (SCAR15)

[edit]A single nucleotide deletion mutation within Rubicon is the cause of Salih ataxia (OMIM ID: 615705). Salih ataxia (also known as spinocerebellar ataxia, autosomal recessive 15 or SCAR15) is a form of spinocerebellar ataxia characterized by progressive loss of coordination of hands, gait, speech, and eye movement.[22] The disease was discovered in children carrying a mutation (c.2624delC p.Ala875ValfsX146) causing a frameshift mutation and an erroneous open reading frame in the Rubicon-coding gene starting from Alanine 875.[23] The resulting disruption of the C-terminal domain impairs Rubicon subcellular localization with Rab7 and late endosomes.[24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000145016 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000035629 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b Zhong Y, Wang QJ, Li X, Yan Y, Backer JM, Chait BT, et al. (April 2009). "Distinct regulation of autophagic activity by Atg14L and Rubicon associated with Beclin 1-phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase complex". Nature Cell Biology. 11 (4): 468–476. doi:10.1038/ncb1854. PMC 2664389. PMID 19270693.

- ^ "RUBCN - Run domain Beclin-1-interacting and cysteine-rich domain-containing protein - Homo sapiens (Human) - RUBCN gene & protein". www.uniprot.org. Retrieved 2022-05-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bhargava HK, Tabata K, Byck JM, Hamasaki M, Farrell DP, Anishchenko I, et al. (July 2020). "Structural basis for autophagy inhibition by the human Rubicon-Rab7 complex". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (29): 17003–17010. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11717003B. doi:10.1073/pnas.2008030117. PMC 7382272. PMID 32632011.

- ^ a b Tabata K, Matsunaga K, Sakane A, Sasaki T, Noda T, Yoshimori T (December 2010). "Rubicon and PLEKHM1 negatively regulate the endocytic/autophagic pathway via a novel Rab7-binding domain". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 21 (23): 4162–4172. doi:10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0495. PMC 2993745. PMID 20943950.

- ^ a b c d e Chang C, Young LN, Morris KL, von Bülow S, Schöneberg J, Yamamoto-Imoto H, et al. (January 2019). "Bidirectional Control of Autophagy by BECN1 BARA Domain Dynamics". Molecular Cell. 73 (2): 339–353.e6. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.035. PMC 6450660. PMID 30581147.

- ^ a b c d e Nakamura S, Oba M, Suzuki M, Takahashi A, Yamamuro T, Fujiwara M, et al. (February 2019). "Suppression of autophagic activity by Rubicon is a signature of aging". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 847. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-08729-6. PMC 6381146. PMID 30783089.

- ^ Heckmann BL, Teubner BJ, Tummers B, Boada-Romero E, Harris L, Yang M, et al. (July 2019). "LC3-Associated Endocytosis Facilitates β-Amyloid Clearance and Mitigates Neurodegeneration in Murine Alzheimer's Disease". Cell. 178 (3): 536–551.e14. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.056. PMC 6689199. PMID 31257024. (Erratum: doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.033, PMID 33306957)

- ^ a b c Fang P, Yu H, Li M, He R, Zhu Y, Liu S (September 2019). "Rubicon: a facilitator of viral immune evasion". Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 16 (9): 770–771. doi:10.1038/s41423-019-0248-7. PMC 6804746. PMID 31164715.

- ^ a b Yang CS, Rodgers M, Min CK, Lee JS, Kingeter L, Lee JY, et al. (March 2012). "The autophagy regulator Rubicon is a feedback inhibitor of CARD9-mediated host innate immunity". Cell Host & Microbe. 11 (3): 277–289. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.019. PMC 3615900. PMID 22423967.

- ^ a b Kim JH, Kim TH, Lee HC, Nikapitiya C, Uddin MB, Park ME, et al. (July 2017). "Rubicon Modulates Antiviral Type I Interferon (IFN) Signaling by Targeting IFN Regulatory Factor 3 Dimerization". Journal of Virology. 91 (14): e00248–17. doi:10.1128/JVI.00248-17. PMC 5487567. PMID 28468885.

- ^ "RUBCN - Run domain Beclin-1-interacting and cysteine-rich domain-containing protein - Homo sapiens (Human) - RUBCN gene & protein". www.uniprot.org. Retrieved 2022-05-30.

- ^ "RCSB PDB - 6WCW: Structure of human Rubicon RH domain in complex with GTP-bound Rab7". RCSB Protein Data Bank. Retrieved 2022-06-30.

- ^ Sun Q, Zhang J, Fan W, Wong KN, Ding X, Chen S, Zhong Q (January 2011). "The RUN domain of rubicon is important for hVps34 binding, lipid kinase inhibition, and autophagy suppression". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (1): 185–191. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.126425. PMC 3012973. PMID 21062745.

- ^ Minami S, Nakamura S, Yoshimori T (2021). "Rubicon in Metabolic Diseases and Ageing". Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 9: 816829. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.816829. PMC 8784836. PMID 35083223.

- ^ Matsunaga K, Saitoh T, Tabata K, Omori H, Satoh T, Kurotori N, et al. (April 2009). "Two Beclin 1-binding proteins, Atg14L and Rubicon, reciprocally regulate autophagy at different stages". Nature Cell Biology. 11 (4): 385–396. doi:10.1038/ncb1846. PMID 19270696. S2CID 205286778.

- ^ a b Tanaka S, Hikita H, Tatsumi T, Sakamori R, Nozaki Y, Sakane S, et al. (December 2016). "Rubicon inhibits autophagy and accelerates hepatocyte apoptosis and lipid accumulation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice". Hepatology. 64 (6): 1994–2014. doi:10.1002/hep.28820. PMID 27637015. S2CID 205902404.

- ^ Yamamuro T, Kawabata T, Fukuhara A, Saita S, Nakamura S, Takeshita H, et al. (August 2020). "Age-dependent loss of adipose Rubicon promotes metabolic disorders via excess autophagy". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 4150. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.4150Y. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17985-w. PMC 7434891. PMID 32811819.

- ^ "Spinocerebellar ataxia, autosomal recessive, 15". www.uniprot.org. Retrieved 2022-05-30.

- ^ Assoum M, Salih MA, Drouot N, H'Mida-Ben Brahim D, Lagier-Tourenne C, AlDrees A, et al. (August 2010). "Rundataxin, a novel protein with RUN and diacylglycerol binding domains, is mutant in a new recessive ataxia". Brain. 133 (Pt 8): 2439–2447. doi:10.1093/brain/awq181. PMID 20826435.

- ^ Assoum M, Salih MA, Drouot N, Hnia K, Martelli A, Koenig M (December 2013). "The Salih ataxia mutation impairs Rubicon endosomal localization". Cerebellum. 12 (6): 835–840. doi:10.1007/s12311-013-0489-4. PMID 23728897. S2CID 12372770.