Dzuluinicob

Province of Dzuluinicob u kuchkabal Ts'ulwinikob (Yucatec Maya) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11th cent.–1544 | |||||||||||||||

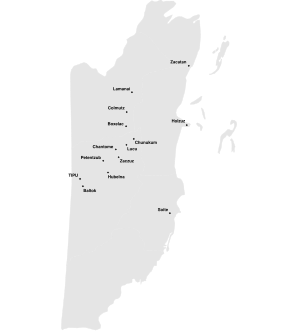

Capital and provincial settlements of Dzuluinicob towards the 16th cent. / in present-day Belize / some locations uncertain / 2022 map following map 2 in Jones 1989 / via Commons[c] | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Dissolved | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Tipu[a] | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Yucatec Maya[b] | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Maya polytheism | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Confederation of towns with aristocratic features | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Postclassic to Spanish conquest | ||||||||||||||

| 10th cent. | |||||||||||||||

• Established | 11th cent. | ||||||||||||||

| 13th cent. | |||||||||||||||

| 1461 | |||||||||||||||

| 1544 | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Belize | ||||||||||||||

a.^ Per Jones 1989, p. 98, Graham 2011, p. 55. b.^ Per Jones 1989, p. 98, Morris et al. 2010, pp. 90–91. c.^ See sec. 'Legacy' subsec. 'Scholarly' in this article for debate regarding inclusion or exclusion of various provincial settlements (eg Lamanai). | |||||||||||||||

Dzuluinicob, or the Province of Dzuluinicob or Ts'ulwinikob, (/zjuːl.ˈwiː.nɪ.kɔːb/ zool-WEE-nih-cawb; Yucatec Maya: u kuchkabal Ts'ulwinikob; Mayan pronunciation: [u kutʃ.ka.ˈbal t͡sʼul.ˌwiː.niː.ˈkoɓ]) was a Postclassic Maya state in the Yucatán Peninsula of the Maya Lowlands.[note 1]

Geography

[edit]Physical

[edit]Dzuluinicob encompassed, at least, most of the Belize River drainage basin.[1][2] Some scholars further locate the drainage basins of the New, Sibun, and Sittee Rivers within the province.[1]

Political

[edit]Dzuluinicob bordered the Chetumal and Waymil provinces to the north, the Mopan and Manche Ch'ol territories to the south, and the Itza, Kowoj, and Yalain polities to the west.[3][4]

History

[edit]Pre-Columbian

[edit]With few notable exceptions, the ninth and tenth centuries of the Classic Maya collapse are thought to have been a period of gradual but marked political and demographic collapse in city-states within what would later become Dzuluinicob.[5][6] Though scarce little is known of the province's pre-Columbian history, given the aforementioned population glut, it has been suggested that Dzuluinicob emerged after a significant wave of immigration into the region.[7][8] It has been further noted that such demographic influx may have been similar and coincident with that which gave rise to the Peten Itza Kingdom, i.e. settlement by northerly aristocratic mayors and their households upon the collapse of Mayapan and consequent disintegration of the regional council of provincial governors.[9][10][note 2] The burgeoning province is thought to have grown much closer to its western neighbours in Peten, given the observed similarity of their pre-Columbian material cultures, than to its northern neighbour, Chetumal, given the observed dissimilarity of their material cultures.[11]

Columbian

[edit]Dzuluinicob is commonly thought to have been the last province conquered during the 1543–1544 Pachecos entrada.[12]

Society

[edit]The province is thought to have been 'a major player in [southern Lowlands] cacao cultivation and trade.'[13] It is further thought to have housed Muzul Maya residents, at least in the capital.[13]

Legacy

[edit]Scholarly

[edit]None of Dzuluinicob's records are extant. Consequently, all scholarship on the province has relied on later Spanish records and modern archaeology. The province was first brought to attention by Grant D. Jones's 1989 Maya Resistance to Spanish Rule, based on 1982–1983 archival research at the General Archive of the Indies.[14][15][16]

The northern half of Belize, which under the Spanish became the greater part of the Bacalar province, was indigenously a province of Yucatec-speakers known as Dzuluinicob. [...] Earlier writers were unaware of the existence of Dzuluinicob and attributed far more influence to the province of Chetumal than it now appears to have had. / Because the sole direct reference to Dzuluinicob as a provincial entity is in a unique early version of Melchor Pacheco's probanza, it would be foolhardy to venture specific claims regarding its territorial limits. I have nonetheless argued throughout this study that Tipu was the political centre of this apparently extensive province, which must have included territory all the way from the Sibun River north to the lower New River.

Aspects of the province as originally delineated have since come into question. For instance, while Jones placed Lamanai within Dzuluinicob, recent literature has noted that pre-Columbian material recovered from Lamanai 'is without any doubt distinctive from that [recovered] at Tipu,' such that 'it is hard to see them [Lamanai and Tipu] as part of a single "provincial" unit.'[18][note 4] Similarly, while Jones originally glossed ts’ul winiko’ob as ‘foreign people,’ in keeping with scholarly consensus then, recent literature has noted that the term might rather mean ‘gentlemen’ or ‘members of the Ts’ul lineage.’[19][20][21][note 5]

Notes and references

[edit]Explanatory footnotes

[edit]- ^ Article-wide notices.

- The Yucatec Mayan orthography in this article follows that of Barrera Vásquez 1980, pp. 41a–44a, except for established names like Dzuluinicob. The province's name is nonetheless spelt Dzuluinikob in Meissner 2014, p. i, and Tz'ul Winikob' in Jones 1998, p. 3.

- Various discordant periodisations of pre-Columbian Maya history are employed in literature (see Periodisation of the history of Belize § Pre-Columbian for relevant background). This article uses Postclassic for AD 900–1500, and Classic for AD 250–900. Earlier periods are not referenced by name.

- Dzuluinicob has been called a chiefdom in lay literature. A distinction has been made, however, between chiefdoms and states, the latter being characterised by more complex forms of sociopolitical organisation than the former (Sharer & Traxler 2006, p. 73, Rice 2004, pp. 4–7). Accordingly, the province is herein designated a state, and not a chiefdom.

- ^ Morris et al. 2010, pp. 85, 90–92, however, suggest a much earlier founding date of circa AD 750–900 for the province, given province-wide dispersal of Ik’hubil-style ceramics during that period.

- ^ The Pacheco probanza is catalogued but not digitised by the Portal de Archivos Españoles under reference number 'ESCRIBANIA,304B'.

- ^ Rather than excluding the New River drainage basin, and thereby excluding Lamanai, from Dzuluinicob, the aforementioned Lamanai–Tipu cultural dissimilarity has led some scholars to exclude the upper portion of the Belize River drainage basin from the province, thereby excluding Tipu as well (Morris et al. 2010, pp. 86, 90).

- ^ The traditional interpretation of ts’ul winiko’ob has been taken to imply that (a) residents of Dzuluinicob were not local to or not culturally similar to those of the northern Maya Lowlands provinces, or (b) they were not under the political or economic influence of the same northern provinces (Jones 1989, pp. 9–12, Walker 2016, pp. 22, 94). The novel interpretations of the term may imply that the province rather housed wealthy or powerful individuals, or that it was ruled by members of the Ts'ul family (Walker 2016, p. 94).

Short citations

[edit]- ^ a b Jones 1989, pp. xvi–xvii, 98.

- ^ Graham 2011, pp. 52, 198.

- ^ Jones 1989, pp. xiv–xvii, 9.

- ^ Graham 2011, p. 54, map 2.4.

- ^ Okoshi et al. 2021, pp. 54, 56–62.

- ^ Arnauld, Beekman & Pereira 2021, cap. 1 introductory sec. para. 6, and concluding sec. para. 1.

- ^ Jones 1989, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Trask 2018, p. 39.

- ^ Quezada 2014, pp. 22, 38.

- ^ Harvey 2018, p. 28.

- ^ Graham 2011, pp. 51–52, 55.

- ^ Quezada 2014, p. 35.

- ^ a b Gomburg 2018, p. 5.

- ^ Graham 2011, pp. 47, 49.

- ^ Jones 1989, pp. xi, xiii, xvi–xvii.

- ^ Walker 2016, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Jones 1989, p. 98.

- ^ Graham 2011, pp. 51, 56–58, 198–199.

- ^ Barrera Vásquez 1980, pp. 892, 923.

- ^ Jones 1989, p. 10.

- ^ Walker 2016, p. 94.

Full citations

[edit]- anon., ed. (2008). A geography of Belize : the land and its people (Rev. 11th ed.). Benque Viejo, Belize: Cubola. OCLC 530699621.

- Arnauld, M. Charlotte; Beekman, Christopher; Pereira, Grégory, eds. (2021). Mobility and Migration in Ancient Mesoamerican Cities. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. OCLC 1178868569.

- Barrera Vásquez, Alfredo, ed. (1980). Diccionario maya Cordemex : maya-español, español-maya. Mérida, Yucatán: Ediciones Cordemex. OCLC 7550928.

- Bracamonte y Sosa, Pedro (2001). La conquista inconclusa de Yucatán : los mayas de la montaña, 1560-1680. Colección Peninsular; Serie Estudios. México, DF: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social : Miguel Angel Porrúa : Universidad de Quintana Roo. ISBN 9707011599. OCLC 49519206.

- Chase, Arlen F.; Rice, Prudence M., eds. (1985). The Lowland Maya Postclassic. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. hdl:2027/txu.059173018481763. ISBN 9780292746435. OCLC 10924247.

- Farris, Nancy M. (1992) [First published 1984 by PUP]. Maya Society under Colonial Rule The Collective Enterprise of Survival (5th corrected reprint of 1st ed.). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691235400. OCLC 1273306087.

- Gomburg, Emmalea (2018). Investigating Possible Scurvy in the Postclassic Maya of Tipu (MA). Hattiesburg, Mississippi: University of Southern Mississippi.

- Graham, Elizabeth A. (2011). Maya Christians and Their Churches in Sixteenth-Century Belize. Maya studies. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. OCLC 751694131.

- Harrison-Buck, Eleanor (2007). Materializing identity among the Terminal Classic Maya: Architecture and ceramics in the Sibun Valley, Belize (PhD). Boston, Massachusetts: Boston University. ProQuest 304897391.

- Harvey, Amanda R. (2018). An Analysis of Maya Foodways: Stable Isotopes and Oral Indicators of Diet in West Central Belize (PhD). Reno, Nev.: University of Nevada, Reno. ProQuest 2082266936.

- Hofling, Charles Andrew, ed. (2011). Mopan Maya - Spanish - English dictionary : diccionario Maya Mopan - Español - Ingles. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press. OCLC 639161518.

- Jones, Grant D. (1989). Maya resistance to Spanish rule : time and history on a colonial frontier. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. hdl:2027/mdp.39015015491791. ISBN 9780826311610. OCLC 20012099.

- Jones, Grant D. (1998). The conquest of the last Maya kingdom. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. hdl:2027/heb.03515. OCLC 38747674.

- Meissner, Nathan J. (2014). Technological systems of small point weaponry of the Postclassic Lowland Maya (a.d. 1400 - 1697) (PhD). Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University. ProQuest 1660540689.

- Messner, Nathan J. (2020). "The Porous Boundary: Comparing Late Postclassic–Early Colonial Maya Projectile Technologies Across Peten and Belize". Ancient Mesoamerica. 31 (3): 526–542. doi:10.1017/S0956536120000140.

- Morandi, Steven J. (2010). Xibun Maya: The archaeology of an early Spanish colonial frontier in southeastern Yucatán (PhD). Boston, Massachusetts: Boston University. ProQuest 305184024.

- Morris, John; Jones, Sherilyne; Awe, Jaime; Thompson, George; Badillo, Melissa, eds. (2010). Archaeological investigations in the eastern Maya lowlands : papers of the 2009 Belize Archaeology Symposium. Research reports in Belizean archaeology. Vol. 7. Belmopan, Belize: Institute of Archaeology, National Institute of Culture and History. ISBN 9789768197368. OCLC 714903259.

- Okoshi, Tsubasa; Chase, Arlen F.; Nondédéo, Philippe; Arnauld, M. Charlotte, eds. (2021). Maya Kingship: Rupture and Transformation from Classic to Postclassic Times. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. OCLC 1193557896.

- Orser, Charles E., ed. (2002). Encyclopedia of Historical Archaeology. London & New York: Routledge. OCLC 47894546.

- Pugh, Timothy W.; Cecil, Leslie G. (2004). Maya Worldviews at Conquest. Mesoamerican Worlds Series. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. OCLC 558844310.

- Quezada, Sergio (2014) [First published 1993 by Colegio de México]. Pueblos y caciques yucatecos, 1550-1580 [Maya lords and lordship : the formation of colonial society in Yucatán, 1350-1600]. Translated by Rugeley, Terry (Revised translation of 1993 Spanish ed.). Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. OCLC 847529166.

- Rice, Prudence M. (2004). Maya Political Science: Time, Astrology, and the Cosmos. The Linda Schele series in Maya and pre-Columbian studies. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. OCLC 60612439.

- Sabloff, Jeremy A.; Andrews V, E. Wyllys, eds. (1986). Late Lowland Maya civilization : classic to postclassic. School of American Research advanced seminar series. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. hdl:2027/txu.059173018481821. ISBN 9780826308368. OCLC 12420464.

- Sharer, Robert J.; Traxler, Loa P., eds. (2006). The Ancient Maya (6th ed.). Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. hdl:2027/mdp.39015062626216. ISBN 9780804748179. OCLC 57577446.

- Smith, Michael E.; Berdan, Frances F., eds. (2003). The postclassic Mesoamerican world. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0874807344. OCLC 50503226.

- Trask, Willa Rachel (2018). Missionization and Shifting Mobility on the Southeastern Maya-Spanish Frontier: Identifying Immigration to the Maya Site of Tipu, Belize Through the Use of Strontium and Oxygen Isotopes (PhD). College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University. hdl:1969.1/174168.

- Walker, Debra S., ed. (2016). Perspectives on the Ancient Maya of Chetumal Bay. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. OCLC 948670056.