COVID-19 pandemic in China

This article needs to be updated. The reason given is: The intro lacks info on the overall course of the pandemic, including the zero-covid policies and the 2022-2023 surge. It has too much focus on Macau. The page lacks any map or up-to-date graph. (June 2023) |

| COVID-19 pandemic in China | |

|---|---|

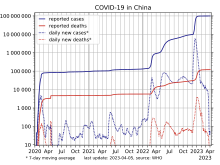

Rolling average of confirmed COVID-19 cases per day in mainland China | |

| Disease | COVID-19 |

| Virus strain | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Location | China |

| First outbreak | Wuhan, Hubei[1] |

| Index case | 1 December 2019 (5 years, 2 weeks and 3 days ago) |

| Recovered | 309,259[2] |

| Vaccinations | |

| History of the People's Republic of China |

|---|

|

|

|

The COVID-19 pandemic in China is part of the worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). China was the first country to experience an outbreak of the disease, the first to impose drastic measures in response (including lockdowns and face mask mandates), and one of the first countries to bring the outbreak under control.

The first wave of the disease manifested as the 2019–2020 COVID-19 outbreak in mainland China, beginning with a cluster of mysterious pneumonia cases, mostly related to the Huanan Seafood Market, in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province. It was first reported to the local government on 27 December 2019, and published on 31 December. On 8 January 2020, a new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) was identified as the cause of the pneumonia by Chinese scientists.[4] By 29 January, the virus was found to have spread to all provinces of mainland China.[5][6][7] The virus was first confirmed to have spread to Hong Kong on 23 January 2020, thus originating the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong.[8] Confirmed cases were generally transferred to Princess Margaret Hospital's Infectious Disease Centre for isolation and centralized treatment. On 5 February, after a five-day strike by front-line medical workers, the Hong Kong government closed all but three border control points – Hong Kong International Airport, Shenzhen Bay Control Point, and Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge Control Point remaining open. The first case of the disease in Macau was confirmed on 22 January 2020, originating the COVID-19 pandemic in Macau. The city saw nine more cases by 4 February, but no more cases until 15 March, when imported cases began to appear.[9] Until 26 April 2021, the city had 49 cumulative confirmed cases of COVID-19, all of those having recovered, and no deaths from the disease.[10] Stringent government measures[11] have included the 15-day closure of all 81 casinos in the territory in February; in addition, effective 25 March, the territory disallowed connecting flights at its airport as well as entry by all non-residents (with the exception of residents of mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan), and from 6 April, the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge was closed to public transport and most other traffic.

Government response

From the start, the Chinese government response pursued a zero-COVID strategy, which aimed to eliminate transmission of the virus within the country and allow resumption of normal economic and social activity; by late 2021 it was one of few countries still pursuing this approach.[12]

On 1 February 2020, the People's Bank of China announced it would temporarily suspend the inclusion of mortgage and credit card payments in the credit record of people impacted by the pandemic.[13]: 134 Private financial credit scoring companies, including Sesame Credit, suspended financial credit ratings.[13]: 134 Various cities established mechanisms to incentivize companies to provide pandemic relief, with measures including whitelisting (referred to in China as redlisting) for those donating funds and supplies with benefits like simplified administrative procedures, increased policy support, or increased financial support.[13]: 135 Following a speech by Xi Jinping emphasizing areas of regulatory compliance, provinces and cities promulgated regulations emphasizing heavy penalties for price hikes, violence against doctors, counterfeit medical supplies, refusal to comply with pandemic prevention measures, and wildlife trade violations.[13]: 134

By late February 2020, the pandemic had been brought under control in most Chinese provinces. On 25 February, the reported number of newly confirmed cases outside mainland China exceeded those reported from within for the first time.[14] By the summer of 2020, widespread community transmission in mainland China had been ended, and restrictions were eased there.[15] As of October 2020 China's economy continued to broaden recovery from the recession during the pandemic, with stable job creation and record international trade growth, although retail consumption was still slower than predicted.[16][17]

By August 2021, China had donated 700 million vaccine doses abroad, an amount more than all other countries had combined.[18]: 199

In 2022, infection rates increased, and on 3 April 2022, China reported 13,146 new cases of COVID-19 in the past 24 hours, which was the highest single-day total of new cases since the height of the 2020 outbreak.[19]

Mainland China

Based on retrospective analysis published in The Lancet in late January 2020, the first confirmed patient started experiencing symptoms on 1 December 2019,[20] though the South China Morning Post later reported that a retrospective analysis showed the first case may have been a 55-year-old patient from Hubei province as early as 17 November 2019.[21][22]

The outbreak went unnoticed until 26 December 2019, when Zhang Jixian, director of the Department of Respiratory Medicine at Hubei Xinhua Hospital, noticed a cluster of patients with pneumonia of unknown origin, several of whom had connections to the Huanan Seafood Market.[23] She subsequently alerted the hospital, as well as municipal and provincial health authorities, which issued an alert on 30 December.[23][24] Results from patient samples obtained on 29–30 December indicated the presence of a novel coronavirus, related to SARS.[23]

On 22 January, 2020 Hubei launched a Class 2 Response to Public Health Emergency.[25] Ahead of the Hubei authorities, a Class 1 Response to Public Health Emergency, the highest response level was announced by the mainland province of Zhejiang on 23 January.[26][27] Around 23 January 2020, stringent measures such as lockdown of Wuhan and the wider Hubei province and face mask mandates were introduced,[28] which lowered and delayed the epidemic peak according to epidemiology modelling.[29] Guangdong and Hunan followed suit later on the day. On the following day, Hubei[30] and 13 other mainland provinces[31][32][33][34] also launched a Class 1 Response. By January 29, 2020 all parts of mainland had initiated a Class 1 Response after Tibet upgraded its response level on that day.[35]

Within three weeks of the first known cases, the government built sixteen large mobile hospitals in Wuhan and sent 40,000 medical staff to the city.[36]: 137 Implementing these measures made Chinese perceptions of the government's response more favorable.[37]: 256

Yet, by 29 January, the virus was found to have spread to all provinces of mainland China.[5][6][38] Hubei Province party secretary Jiao Chaoliang was removed from office for failing to contain the outbreak.[39]: 194–195 On 31 January 2020 the World Health Organization declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.[38] A severe shortage of face masks and other protective gear[40] led several countries in February 2020 to send international aid, including medical supplies, to China.[41][42][43]

In June 2020, the Sinopharm BIBP vaccine (BBIBP-CorV) was authorized for emergency use in China. On July 22 2020 Chinese authorities started the emergency use of COVID-19 vaccines.[44] As of July 2022, it was estimated that about 89.7% of the country's population had received a vaccine, and about 56% of the population had received a booster dose.[45]

China was one of a small number of countries that have pursued an elimination strategy, sustaining low case numbers between the 2020 outbreak until early 2022. China's response to the initial Wuhan COVID-19 outbreak has been both praised and criticised. Some have criticised the censorship of information that might be unfavorable for local officials. Observers have attributed this to a culture of institutional censorship affecting the country's press and Internet. The government censored whistleblowers, journalists, and social media posts about the outbreak. During the beginning of the pandemic, the Chinese government made efforts to clamp down on discussion and hide reporting about it. Efforts to fund and control research into the virus's origins and to promote fringe theories about the virus have continued up to the present.[46] In October 2020, The Lancet Infectious Diseases reported: "While the world is struggling to control COVID-19, China has managed to control the pandemic rapidly and effectively."[47] By late 2020, China had contained the first wave of COVID-19.[48]: 170

E-commerce contributed substantially to China's COVID-19 pandemic response by facilitating fast delivery of personal protective equipment, food, and daily use consumer goods during lockdowns.[48]: 159

Ultimately, lockdowns in China were highly effective in reducing the spread of COVID-19; for several years, there was wide public consensus in China that the benefits outweighed the costs.[49]: 67

December 2022 surge

Nationwide protests broke out in November 2022 amid growing discontent among residents over the zero-COVID policy and the resulting economic costs.[50] Following the easing of the Zero-COVID strategy in December 2022, Beijing reported a surge in COVID-19 infections.[51][52] It was reported that restaurants and food delivery services had closed due to staff infections, and pharmacies had been emptied of medicine and disinfectant solution.[53] On 22 December, a report by UK research firm Airfinity modelling based on regional Chinese data estimated that more than 5,000 people were dying each day from COVID-19 in China, with cases rising fastest in Beijing and Guangdong province.[54] Internal minutes from a meeting of China's National Health Commission held on 21 December revealed that as many as 248 million people in China might have contracted COVID-19 over the first 20 days of December, and up to 37 million on a single day.[55]

On 23 December 2022 Qingdao's municipal health chief Bo Tao stated that the city was seeing "between 490,000 and 530,000" new infections each day and on the same day, Dongguan's health commission declared on its Weixin account that the city had 250,000 to 300,000 people being infected every day.[56] Officials in Yulin, a city of 3.6 million people in Shaanxi province, logged 157,000 new infections with models estimating more than a third of the city's population had already been infected. [57] On 25 December 2022, the National Health Commission announced that it would no longer report daily COVID-19 figures,[58] and Zhejiang provincial government said it was battling around a million new infections a day and expected the number to be doubling in days ahead.[59]

Special administrative regions

Hong Kong

Hong Kong was relatively unscathed by the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak and had a flatter epidemic curve than most other places, which observers consider remarkable given its status as an international transport hub. Furthermore, its proximity to China and its millions of mainland visitors annually would make it vulnerable.[60] Some experts now believe the habit of wearing masks in public since the SARS epidemic of 2003 may have helped keep its confirmed infections at 845, with four deaths, by the beginning of April.[60] In a study published in April 2020 in the Lancet, the authors expressed their belief that border restrictions, quarantine and isolation, social distancing, and behavioural changes such as wearing masks likely all played a part in the containment of the disease up to the end of March.[61] Others attributed the success to critical thinking of citizens who have become accustomed to distrusting the competence and political motivations of the government, the World Health Organization, and the Chinese Communist Party.[62]

After a much smaller second wave in late March and April 2020 caused by overseas returnees rushing to beat mandatory quarantine,[63] Hong Kong saw a substantial uptick in COVID cases in July, with more than a hundred cases being reported several days in a row until early August. Experts attributed this third wave to imported cases – sea crew, aircrew members, and domestic helpers made up the majority of 3rd wave infections.[64] In late November 2020, the city entered a fourth wave, called "severe" by Chief Executive Carrie Lam. The initial driver behind the fourth wave was a group of dance clubs in which wealthy, predominantly female Hong Kongers danced together and had dance lessons with mostly younger male dance instructors.[65] Measures taken in response included a suspension of school classroom teaching until the end of the year, and an order for restaurants to seat only two persons per table and close at 10:00 p.m. taking effect on 2 December;[66] a further tightening of restrictions saw, among other measures, a 6 pm closing time of restaurants starting from 10 December, and a mandate for authorities to order partial lockdowns in locations with multiple cases of COVID-19 until all residents were tested.[67] From late January 2021, the government pursued repeatedly locked down residential buildings to conduct mass testing. A free mass vaccination program with the Sinovac vaccine and Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine was launched on 26 February 2021.[citation needed] The government sought to counter the vaccine hesitancy by material incentives, which led to an acceleration of vaccinations in June.[68]

Hong Kong is one of few countries and territories to pursue a "zero-COVID" elimination strategy, by essentially closing all its borders and, until February 2022, subjecting even mild and asymptomatic cases to hospitalisation, and sometimes isolation extending over several weeks. The fifth, Omicron variant driven wave of the pandemic emerging in late December 2021[69] caused the health system to be stretched to its limits, the mandatory hospitalization to be abandoned,[70] and led several experts to question the zero-COVID strategy. Some even considered it counterproductive, due to it having nourished hopes that the city would eventually become free of the virus, and thus having led to a low COVID-19 vaccination rate in the city.[71] Most of the deaths in the fifth wave were among the unvaccinated elderly.[72]

Macau

At a press conference in February 2020, Ho Iat Seng welcomed mainland Chinese people to make use of Macau's free medical service. This created controversy online, with users worrying that people from the mainland would come to Macau and spread the virus. Afterwards, Secretary for Administration and Justice Cheong Weng Chon (張永春) said that any patients from outside Macau who had COVID-19 would need to pay their own medical bills; they would be able to apply for a fee waiver, and the government would make a decision based on their financial situation and effects on the public.[73]

When Guangdong became the province with the second-most cases in China, Macau still had tens of thousands of people going to and from Zhuhai every day. Many people asked for the border to be closed, but the government repeatedly said that a complete closure was not possible. Ho Iat Seng said, "If we closed all the ports of entry, who would remove the trash? Who would handle security? How would we get fresh produce? These are the issues we're thinking about."[74][75]

Republic of China (Taiwan)

Since its establishment after the Chinese Civil War, the PRC has claimed the territories governed by the Republic of China (ROC), a separate political entity today commonly known as Taiwan, as a part of its territory. The Chinese government regards the island of Taiwan as its Taiwan Province. Historically, the Taiwanese government has also stated that it is the legitimate government of all of China.

The virus was confirmed to have spread to Taiwan on 21 January 2020, with the first case being a 50-year-old woman who had been teaching in Wuhan, China.[76] The Taiwanese government integrated data from the national health care system, immigration, and customs authorities to aid in the identification and response to the virus. Government efforts are coordinated through the National Health Command Center (NHCC) of the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control, established to aid in disaster management for epidemics following the 2003 SARS outbreak.[77][78] The Journal of the American Medical Association says Taiwan engaged in 124 discrete action items to prevent the spread of the disease, including early screening of flights from Mainland China and the tracking of individual cases.[79][80]

Starting 19 March 2020, foreign nationals were barred from entering Taiwan with some exceptions such as those carrying out the remainder of business contracts and those holding valid Alien Resident Certificates, diplomatic credentials, or other official documentation and special permits.[81] Restrictions have since been relaxed for foreign university students and those seeking medical treatment in Taiwan, subject to prior government approval.[82][83] All who are admitted into the country must complete a fourteen-day quarantine upon arrival, except for business travelers from countries determined to be at low or moderate risk, who are subject to five- or seven-day quarantines and must submit to a COVID-19 test.[84][85]

In response to the worldwide spike in cases in October and November 2020, Taiwan announced that all travelers to and transiting through Taiwan, regardless of nationality, origin, or purpose, must submit a negative COVID-19 test performed within three working days of arrival.[86][87][88][89] Exceptions are granted to travelers responding to family emergencies or arriving from countries where on-demand or self-paid tests are unavailable, but they are required to be seated apart from other passengers and take a self-paid test immediately on arrival in Taiwan.[90]

In 2020, the pandemic had a smaller impact in Taiwan than in most other industrialized countries, with a total of seven deaths.[91][92] The number of active cases in this first wave peaked on 6 April 2020, at 307 cases, the overwhelming majority of which were imported.[93] Taiwan's handling of the outbreak has received international praise for its effectiveness in quarantining people.[80][94]

However, an outbreak among Taiwanese crew members of the state-owned China Airlines in late April 2021 led to a sharp surge in cases, mainly in the Greater Taipei area, from mid May. In response, the closure of all schools in the area from kindergarten to high schools was mandated for two weeks, and national borders were closed for at least a month to those without a residence permit, among other measures.[95] In addition to a low testing rate and the recent shortening of the quarantine period for pilots to just three days,[96] Taiwanese medical experts said that they had expected the flare-up due to the emergence of more transmissible variants of the coronavirus (the Alpha variant was found in many of those linked to the China Airlines cluster[96]), combined with the slow progress of Taiwan's vaccination campaign. Critics linked the latter issue to several factors, including Taiwan's strategy of focusing on its own vaccine development and production, making it less ready to quickly buy overseas vaccines once those became available; and hesitation among residents to get vaccinated due to previously low case numbers.[97] Additionally, heavy reporting on rare side effects of the AstraZeneca vaccine was believed to have played a role. Demand for vaccines greatly increased, however, with the surge in cases from May 2021.[98]

As of 23 April 2022, 14,214,319 tests had been conducted in Taiwan, of which 51,298 were confirmed cases, including 856 deaths.[99]

References

- ^ Sheikh, Knvul; Rabin, Roni Caryn (10 March 2020). "The Coronavirus: What Scientists Have Learned So Far". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ 截至12月8日24时新型冠状病毒肺炎疫情最新情况 (in Chinese (China)). National Health Commission. 8 December 2022. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Mathieu, Edouard; Ritchie, Hannah; Rodés-Guirao, Lucas; Appel, Cameron; Giattino, Charlie; Hasell, Joe; Macdonald, Bobbie; Dattani, Saloni; Beltekian, Diana; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban; Roser, Max (2020–2024). "Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)". Our World in Data. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ Khan, Natasha (9 January 2020). "New Virus Discovered by Chinese Scientists Investigating Pneumonia Outbreak". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b 眾新聞 | 【武漢肺炎大爆發】西藏首宗確診 全國淪陷 內地確診累計7711宗 湖北黃岡疫情僅次武漢. 眾新聞 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b Chappell, Bill (30 January 2020). "Coronavirus Has Now Spread To All Regions Of mainland China". NPR. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus declared global health emergency". BBC News. 31 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Cheung, Elizabeth (22 January 2020). "China coronavirus: death toll almost doubles in one day as Hong Kong reports its first two cases". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020.

- ^ Keegan, Matthew (24 March 2020). "Lessons From Macau, the Densely Populated Region Beating Back COVID-19". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 10 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "Macao Government Special webpage against Epidemics". Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, Macau. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ Lou, Loretta (26 March 2021). "Casino capitalism in the era of COVID-19: examining Macau's pandemic response". Social Transformations in Chinese Societies. 17 (2): 69–79. doi:10.1108/STICS-09-2020-0025. S2CID 233650925. Archived from the original on 25 April 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ Normile, Dennis (19 November 2021). "'Zero COVID' is getting harder—but China is sticking with it". Science. 374 (6570): 924. Bibcode:2021Sci...374..924N. doi:10.1126/science.acx9657. eISSN 1095-9203. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 34793217. S2CID 244403712.

- ^ a b c d Brussee, Vincent (2023). Social Credit: The Warring States of China's Emerging Data Empire. Singapore: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 9789819921881.

- ^ "WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the mission briefing on COVID-19 – 26 February 2020". World Health Organization. 26 February 2020. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Lancet, The (25 July 2020). "COVID-19 and China: lessons and the way forward". The Lancet. 396 (10246): 213. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31637-8. PMC 7377676. PMID 32711779.

- ^ "China's economy continues to bounce back from virus slump". BBC News. 19 October 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ "China's economic recovery continues but signals mixed in October". Nikkei Asia. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Cheng, Wenting (2023). China in Global Governance of Intellectual Property: Implications for Global Distributive Justice. Palgrave Socio-Legal Studies series. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-031-24369-1.

- ^ "China reports 13,000 Covid cases, most since end of Wuhan's first wave". France 24. 4 March 2022. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Huang, Chaolin; Wang, Yeming; Li, Xingwang; Ren, Lili; Zhao, Jianping; Hu, Yi; Zhang, Li; Fan, Guohui; Xu, Jiuyang; Gu, Xiaoying; Cheng, Zhenshun (15 February 2020). "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China". The Lancet. 395 (10223): 497–506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7159299. PMID 31986264.

- ^ "China's first confirmed Covid-19 case traced back to November 17". South China Morning Post. 13 March 2020. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Davidson, Helen (13 March 2020). "First Covid-19 case happened in November, China government records show—report". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Yu, Gao; Yanfeng, Peng; Rui, Yang; Yuding, Feng; Danmeng, Ma; Murphy, Flynn; Wei, Han; Shen, Timmy (29 February 2020). "In Depth: How Early Signs of a SARS-Like Virus Were Spotted, Spread, and Throttled". Caixin Global. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ www.bjnews.com.cn. "武汉疾控证实:当地现不明原因肺炎病人,发病数在统计". www.bjnews.com.cn. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ 湖北省人民政府关于加强新型冠状病毒感染的肺炎防控工作的通告. Hubei Province People's Government. 21 January 2020. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ 杨利, ed. (23 January 2020). 浙江新增新型冠状病毒感染的肺炎确诊病例17例. Provincial Health Commission of Zhejiang via The Beijing Times. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ 俞菀 (23 January 2020). 周楚卿 (ed.). 浙江:新增新型冠状病毒感染肺炎确诊病例17例 启动重大公共突发卫生事件一级响应 (in Chinese (China)). Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ Cadell, Cate; Chen, Yawen (8 April 2020). "'Painful lesson': how a military-style lockdown unfolded in Wuhan". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Prem, Kiesha; Liu, Yang; Russell, Timothy W.; Kucharski, Adam J.; Eggo, Rosalind M.; Davies, Nicholas; Flasche, Stefan; Clifford, Samuel; Pearson, Carl A. B.; Munday, James D.; Abbott, Sam (1 May 2020). "The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: a modelling study". The Lancet Public Health. 5 (5): e261–e270. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30073-6. ISSN 2468-2667. PMC 7158905. PMID 32220655.

- ^ 多个省市启动一级响应抗击疫情,为何湖北省却不是最快的?. 第一财经 [China Business Network]. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ 北京市启动重大突发公共卫生事件一级响应. Beijing Youth Daily. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ 上海、天津、重庆、安徽启动重大突发公共卫生事件一级响应机制. Xinhua News Agency. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ 储白珊 (24 January 2020). 福建启动重大突发公共卫生事件一级响应机制. 福建日报. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ 苏子牧 (24 January 2020). 【武汉肺炎疫情】中国14省市启动一级响应. 多维新闻. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ 中国内地31省份全部启动突发公共卫生事件一级响应. Caixin. 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Jin, Keyu (2023). The New China Playbook: Beyond Socialism and Capitalism. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-1-9848-7828-1.

- ^ Shi, Song (2023). China and the Internet: Using New Media for Development and Social Change. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9781978834736.

- ^ a b "Coronavirus declared global health emergency". BBC News. 31 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Marquis, Christopher; Qiao, Kunyuan (2022). Mao and Markets: The Communist Roots of Chinese Enterprise. New Haven: Yale University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv3006z6k. ISBN 978-0-300-26883-6. JSTOR j.ctv3006z6k. OCLC 1348572572. S2CID 253067190.

- ^ Safi (now), Michael; Rourke (earlier), Alison; Greenfield, Patrick; Giuffrida, Angela; Kollewe, Julia; Oltermann, Philip (3 February 2020). "China issues 'urgent' appeal for protective medical equipment – as it happened". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ "Equatorial Guinea donates $2m to China to help combat coronavirus". Africanews. 5 February 2020. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "Feature: Japan offers warm support to China in battle against virus outbreak – Xinhua". Xinhuanet.com. 13 February 2020. Archived from the original on 10 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ "China's Xi Writes Thank-You Letter to Bill Gates for Virus Help". Bloomberg. 21 February 2020. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ "中国于7月22日启动新冠疫苗紧急使用 接种人数超2万". Jiefang Daily. 23 August 2020. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Liu, Roxanne; Tian, Yew Lun (24 July 2022). "Two years after drive began, China reveals Xi Jinping received local COVID vaccine". The Age. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 24 July 2022. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ Cheng, Maria; Kang, Dake; McNeil, Sam (30 December 2020). "China clamps down in hidden hunt for coronavirus origins". AP News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ Burki, Talha (8 October 2020). "China's successful control of COVID-19". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 20 (11): 1240–1241. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30800-8. PMC 7544475. PMID 33038941.

- ^ a b Liu, Lizhi (2024). From Click to Boom: The Political Economy of E-Commerce in China. Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9780691254111. ISBN 9780691254104. JSTOR jj.14527541.

- ^ Zhang, Angela Huyue (2024). High Wire: How China Regulates Big Tech and Governs Its Economy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197682258.

- ^ "Protests erupt across China in unprecedented challenge to Xi Jinping's zero-Covid policy". CNN. 26 November 2022. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ Kang, Dake (24 December 2022). "Packed ICUs, crowded crematoriums: COVID roils Chinese towns". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ Feng, Emily (23 December 2022). "Fears of a 'dark COVID winter' in rural China grow as the holiday rush begins". NPR. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "As Covid Spreads Fast, Beijing Isn't in Lockdown. But It Feels Like It". The New York Times. 13 December 2022. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "China COVID deaths probably running above 5,000 per day - UK research firm Airfinity". Reuters. 22 December 2022. Archived from the original on 6 January 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "China Estimates Covid Surge Is Infecting 37 Million People a Day". Bloomberg. 23 December 2022. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Chinese Cities Reveal Covid Cases Surpassing National Tally". Time. 24 December 2022. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ Che, Chang (25 December 2022). "Covid Is Spreading Rapidly in China, New Signs Suggest". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ Griffiths, Robbie (25 December 2022). "China has stopped publishing daily COVID data amid reports of a huge spike in cases". NPR. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ "China's Zhejiang has 1 mln daily COVID cases, expected to double". Reuters. 25 December 2022. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ^ a b "To mask or not to mask: WHO makes U-turn while US, Singapore abandon pandemic advice and tell citizens to start wearing masks". South China Morning Post. 4 April 2020. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Cowling, Benjamin; Ali, Sheikh Taslim; Ng, Tiffany; Tsang, Tim; Li, Julian; Fong, Min Whui; et al. (17 April 2020). "Impact assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: an observational study". The Lancet. 5 (5): e279–e288. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30090-6. PMC 7164922. PMID 32311320.

- ^ Tufekci, Zeynep (12 May 2020). "How Hong Kong Did It". The Atlantic. MSN. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "How Hong Kong squashed its second coronavirus wave". Fortune. 21 April 2020. Archived from the original on 13 December 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Ting, Victor; Cheung, Elizabeth (21 July 2020). "How did Hong Kong's third wave of Covid-19 infections start?". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ "Dance off: the niche social scene behind Hong Kong's biggest Covid-19 cluster". South China Morning Post. 26 November 2020. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ Kwan, Rhoda (30 November 2020). "Hong Kong tightens Covid-19 rules – group gatherings limited to 2, eateries to close 10pm, new hotline for rule-breakers". Hong Kong Free Press. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ Chau, Candice (8 December 2020). "Hong Kong plans partial lockdowns for Covid-19 hotspots and more tests, as number of new infections surges". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ Soo, Zen (17 June 2021). "Get a jab, win a condo: Hong Kong tries vaccine incentives". AP News. Archived from the original on 13 February 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ Lam, Nadia (12 January 2022). "Coronavirus: how Omicron is spreading in Hong Kong wave triggered by Cathay Pacific aircrew and a relative linked to 32 other confirmed infections". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Su, Xinqi; Chen, Dene-Hern (21 February 2022). "Covid-19: 2 years on, Hong Kong reels in worst-ever outbreak – how did we get here?". Hong Kong Free Press. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Master, Farah (21 February 2022). "Analysis: Hong Kong's 'zero-COVID' success now worsens strains of Omicron spike". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Torode, Greg; Roantree, Anne Marie (13 March 2022). "Hong Kong reports 32,430 COVID cases, 264 deaths". Reuters. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ "衛局:不獲批追收鄂婦治療費". 澳門日報. 7 February 2020. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020.

- ^ "當斷不斷 反受其亂 防控疫戰 封關制勝". 訊報. 7 February 2020. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020.

- ^ "賀一誠:澳門不會封關 目前經濟損失仍可承擔". AASTOCKS.COM. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ Chen, Wei-ting; Kao, Evelyn (21 February 2020). "WUHAN VIRUS/Taiwan confirms 1st Wuhan coronavirus case (update)". Central News Agency. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ Wang, C. Jason; Ng, Chun Y.; Brook, Robert H. (3 March 2020). "Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: Big Data Analytics, New Technology, and Proactive Testing". JAMA. 323 (14): 1341–1342. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3151. PMID 32125371. S2CID 211831388.

- ^ Dewan, Angela; Pettersson, Henrik; Croker, Natalie (16 April 2020). "As governments fumbled their coronavirus response, these four got it right. Here's how". CNN. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Duff-Brown, Beth (3 March 2020). "How Taiwan Used Big Data, Transparency and a Central Command to Protect Its People from Coronavirus". Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and the Stanford School of Medicine. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ a b Jennings, Ralph (4 March 2020). "Why Taiwan Has Just 42 Coronavirus Cases while Neighbors Report Hundreds or Thousands". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ Chang, Ming-hsuan; Huang, Frances; Chen, Christie. "Taiwan to bar entry of foreign nationals to combat COVID-19 (Update)". Central News Agency. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Chang, Ming-hsun; Chen, Wei-ting; Cheng, Chih-chung; Kao, Evelyn (22 July 2020). "Taiwan to allow return of all final year international students". Central News Agency. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Yen, William (23 July 2020). "Taiwan to allow entry of foreign nationals seeking medical care". Central News Agency. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Yen, William (2 August 2020). "Hong Kong and Australia removed from low risk category: CECC". Central News Agency of the Republic of China. Focus Taiwan. Archived from the original on 23 July 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "Regulations concerning short-term business travelers' applications for shortened quarantine periods in Taiwan". Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "12月1日秋冬防疫專案啟動,請民眾及醫療院所主動配合相關措施" [The autumn and winter epidemic prevention project was launched on 1 December. The public and medical institutions are requested to actively cooperate with relevant measures] (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ Liao, George (16 November 2020). "Taiwan announces basics of new virus prevention measures". Taiwan News. Luis Ko. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Chen, Wei-ting; Yeh, Joseph (18 November 2020). "Negative COVID-19 tests compulsory for all arrivals next month". Central News Agency of the Republic of China. Focus Taiwan. Archived from the original on 18 November 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ "FAQs concerning COVID-19 RT-PCR test reports issued within 3 days of boarding". Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. 24 March 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ Hsu, Chih-wei; Chang, Ming-hsuan; Yeh, Joseph (25 November 2020). "CECC lists exemptions from compulsory COVID-19 tests for all arrivals". Central News Agency of the Republic of China. Focus Taiwan. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ "新增1例境外移入COVID-19病例,自美國入境" (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. 11 April 2021. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban; Beltekian, Diana; Mathieu, Edouard; Hasell, Joe; MacDonald, Bobbie; Giattino, Charlie; Appel, Cameron; Rodés-Guirao, Lucas; Roser, Max (26 May 2020). "Taiwan: Coronavirus Pandemic Country Profile". Our World in Data. Global Change Data Lab. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ 2020/4/28 14:00 中央流行疫情指揮中心嚴重特殊傳染性肺炎記者會 [28 April 2020 Press Conference on the Severe Pneumonia held by the Central Epidemic Command Center] (in Chinese). Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. 28 April 2020. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Barron, Laignee (13 March 2020). "Coronavirus Lessons from Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong". Time. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ Yang, William (18 May 2021). "Is Taiwan's COVID success story in jeopardy?". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021 – via MSN News.

- ^ a b Tan, Yvette (20 May 2021). "Covid-19: What went wrong in Singapore and Taiwan?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Zhong, Raymond; Chien, Amy Chang (21 May 2021). "'This Day Was Bound to Come': Taiwan Confronts a Covid Flare-Up". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Zennie, Michael; Tsai, Gladys (21 May 2021). "How a False Sense of Security, and a Little Secret Tea, Broke Down Taiwan's COVID-19 Defenses". Time. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ "Taiwan Centers for Disease Control". Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

External links

- Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases and historical data by Johns Hopkins University

- Reports on the COVID-19 pandemic in China, by the PRC National Health Commission

- Coronavirus China updates and news Archived 28 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine. China in Coronavirus Global international portal. Available in English, French, Spanish, Russian and more.