Dora Wheeler Keith

Dora Wheeler Keith | |

|---|---|

Miss Dora Wheeler by William Merritt Chase, oil on canvas, 1883, collection Cleveland Museum of Art | |

| Born | Lucy Dora Wheeler March 12, 1856 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | December 7, 1940 (aged 84) Brooklyn, New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Prospect Cemetery in Jamaica, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Realist painter; illustrator; designer |

| Spouse | Boudinot Keith |

| Parent(s) | Thomas Mason Wheeler Candace Thurber Candace Thurber Wheeler |

| Signature | |

Dora Wheeler Keith (née Lucy Dora Wheeler; March 12, 1856 – December 7, 1940), also known as Mrs. Boudinot Keith, was a portrait artist, muralist, designer and illustrator of books and magazines, and designer of tapestries for her mother Candace Wheeler's firm, the Associated Artists.

Biography

[edit]Birth, early education, and marriage

[edit]Dora Wheeler was born Lucy Dora Wheeler at Nestledown, the Hollis (near Jamaica), Long Island, NY, country house her parents, Candace Wheeler (née Thurber) and Thomas Mason Wheeler, had built in 1854. Artist Sanford Gifford had cradled Dora in his arms and her mother remarked, "It was inevitable that this child should grow up a painter; it began in her babyhood."[1]

Her mother Candace Wheeler was an author, artist/designer, entrepreneur, and a nationally known expert on decorative textiles and interiors, celebrated for championing women as artists and designers.[2] Her father Thomas Mason Wheeler was a businessman involved with shipping in New York harbor, a "clever progressive man" supportive of his wife and daughter in their artistic aspirations.[3]

Dora attended a Quaker school on Stuyvesant Square and subsequently "Miss Haines and Mlle. de Janon's", a New York finishing school on Grammercy Park near the Wheelers' town house.[4] In Europe, where her family spent periods of time after the Civil War, she was enrolled at a boarding school in Wiesbaden, Germany, at ages 9–10 and 15, and also in Zurich, Switzerland. She also spent time with her family in Paris while recovering from illness. They spent summers in Montreux, Switzerland, and at Luc sur Mer, on the French coast.[5][6]

According to her mother, an accident on a long flight of marble stairs in Europe "had much to do with Dora's future, for the absolute bodily inaction which seemed to be a condition of her recovery was so at odds with her mental activity that it resulted in the constant use of her pencil. For months she drew incessantly..."[7]

Dora had already established herself as a young artist, first working with her mother at the Associated Artists, then with a series of book illustrations and portraits of famous authors when in 1890 she married lawyer Boudinot Keith (1859–1925).[8][9] After the marriage she often worked under the name Dora Wheeler Keith, while in later years using the name Mrs. Boudinot Keith for philanthropy such as donating the famous Chase portrait to the Cleveland Museum of Art in 1922, and a collection of 27 Associated Artists textiles to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1928.[10] Dora had two children, a son Elisha, an aspiring landscape painter who died of disease in the Battle of the Somme in the First World War, and a daughter Lois, later Mrs. Clyde V. Simpson.[11][12] Mrs. Keith visited her son’s grave in France in a Gold Star Mother contingent in 1929.

Art training

[edit]

The Wheelers cultivated the company of artists, and were early patrons of the Tenth Street Studio artists who were to be dubbed the Hudson River School.[14] Family friends in Dora's youth included Frederic Edwin Church, Sanford Gifford, Jervis McEntee, John Frederick Kensett, John Lafarge, Worthington Whittredge, Albert Bierstadt, George Inness and J. Alden Weir.[15]

As a young lady in New York, Dora received private instruction from artist William Merritt Chase, from 1879 to 1881.[16][17] She and her friends Rosina and Lydia Emmet were Chase's first pupils and he remained her mentor and close friend throughout his life, an inspiring teacher "not only giving exhaustively of his stored knowledge of how to do things, but fostering as well the will to do it."[18] In subsequent years Dora Wheeler and Chase periodically worked together, for instance collaborating on a series of theatrical tableaux at Madison Square Garden to raise funds for the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty in 1884; she also served on the Executive Board of Chase's Shinnecock Hills school.[19][20]

After her tutelage with Chase, Wheeler studied art in New York at the Art Students League and spent two years at the Académie Julian in Paris.[21][19] While studying in Paris in 1885 she completed one of her earliest designs depicting women in art and literature for which she was to become famous: Penelope Unraveling her Tapestry At Night inspired by Homer's Oddessy, now the only figurative tapestry by the Associated Artists known to survive.[22]

Career as an artist

[edit]Dora Wheeler's first artwork published under her own name was a Christmas card design that won first prize in the Prang competition in 1881.[23] During the 1880s Wheeler enjoyed success as a book and magazine illustrator, and published chromolithographs in Art Amateur.[24] She designed the covers, title page and illustrations for her mother's books, Content in a Garden (New York and Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1901) and Doubledarling and the Dreamspinner (New York, Fox Duffield, 1905); and a cover for Edgar Allen Poe's collected works (New York, Harper and Brothers,1884).[25] She also illustrated Mary D. Brine's My Boy and I (1881); Lucy Larcom's The Cross and the Grail (1886); Mary Matthews Baines' Epithalamium (1889); Annie Flint's Sunbeam Stories and Others (1897); Parsifal (c. 1904); and Annie Flint's Vignettes of Onteora (1914).[26] During the 1880s, Dora Wheeler also embarked on a series of portraits of the leading literary lights of her time, including Harriet Beecher Stowe, Frank Stockton, William Dean Howells, Charles Dudley Warner, and Walt Whitman.[21][27] Her portrait of close Wheeler family friend Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known by his pen name Mark Twain (executed during a visit to Hartford in 1886), as well as her portraits of his wife and daughters, now hang in the Mark Twain House in Hartford, Connecticut.[21][27][28]

Dora Wheeler's first major public project was a mural painted on canvas and mounted on the ceiling of the Library of the Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893.[30] The New York Times said of the mural: "[t]here was a time when no woman would ever have dreamed of undertaking a piece of elaborate mural painting. Yet a New York woman —Mrs. Dora Wheeler Keith — has accomplished results in this field which must astonish even the most enthusiastic believer in women's capabilities. It is an extraordinary achievement in its line..." After the fair the mural was reportedly purchased by the New York State commissioner and installed in the capital building in Albany; it was destroyed there in a fire in 1911.[31][32] Wheeler also exhibited the painting Daphne's Nymphs in the rotunda of the Woman's Building.[31][33]

Dora Wheeler maintained three studios: a refurbished garret at the Associated Artists headquarters, 115 East 23rd Street; at the Wheeler's summer retreat in the Catskills; and in Thomasville, GA, at the Wheelers' winter house, Wintergreen. Chase painted his portrait of Dora in her 23rd Street studio against a shimmering gold silk backdrop, possibly one of the Associated Artists' embroidered fabrics.[19][34] The painting was intended as an exhibition piece for the 1883 European art season and received a gold medal in Munich; it is now in the Cleveland Museum of Art.[35]

Dora's New York studio became a popular rendezvous for artists, writers, and luminaries of contemporary New York, perhaps, her mother thought, because of the "novelty of the introduction of the women element."[36] Lillie Langty for whom Dora had designed three silk tapestries featuring Cupids at play, was a visitor to Dora's studio. Another day "who but Oscar Wilde should wander in one afternoon" (self-invited—Candace speculated nobody was willing to introduce him).[37][38] John Singer Sargent rented her studio for a season, where he painted the portrait La Carmencita now in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris, and the portrait of Beatrix Goelet called The Little Girl and the Parrot.[39][40] Swedish artist Anders Zorn painted in Dora's studio the year following.[31]

Dora's Catskills studio was built in a corner of the garden at Pennyroyal, the family's summer house at the Catskills mountain artist colony called Onteora, co-founded by her mother. Her young nephew Henry L. Stimson used to play with her brother Dunham Wheeler in a corner of the house nicknamed "the Armory"; she painted Stimson's portrait as a child.[41] She also painted portraits of many celebrated visitors on the east wall of Pennyroyal; only her chalk drawing of Mark Twain has survived renovations.[32][42][19]

Dora and her mother Candace were inseparable; they collaborated on art and business endeavors and lived together or nearby most of their lives, even after Dora's marriage to Boudinot Keith: "the two were so close it is hard to delineate where Candace Wheeler ended and Dora Wheeler began."[43] They collaborated on books as author and designer/illustrator, respectively. Dora was the primary figure designer for textiles for her mother's enterprise Associated Artists, producing tapestry designs including those used in the parlor of the Vanderbilt Mansion.[29] Her needlewoven tapestries showing Minnehaha, the Winged Moon, and The Birth of Psyche, hung in a London exhibition of American Art with John Lafarge stained glass windows.[38]

She was elected an academician of the National Academy of Design in 1906.[32]

Death

[edit]Dora Wheeler died in December 1940.[21] She was survived by her daughter, Mrs. Clyde V. Simpson; two nieces, Miss Candace Stimson and Mrs. George Riggs of Port Washington; and by her nephew Henry L. Stimson, then Secretary of War serving President Franklin Roosevelt on the eve of the Second World War.[21]

Gallery and museum collections

[edit]Little is left of the tapestries and nothing known of possible surviving elements of the Chicago mural, for which Dora Wheeler Keith was most famous in her day, that may have escaped the Albany fire of 1911.[44] She is now known primarily for portraits represented in the collections of the Brooklyn Museum, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Boston Public Library, the New York Historical Society, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Princeton University, the Smithsonian Institution National Portrait Gallery, the High Museum of Art, and in private collections.[21][45]

-

Penelope Unraveling Her Work at Night, 1886 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

-

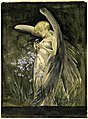

Fairy in Irises, 1888 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

-

Portrait of Laurence Hutton, 1894 (Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton)

Illustrations in books

[edit]Mary Dow Brine, My Boy and I, or, On the Road to Slumberland (Cambridge: University Press, J. Wilson and son, 1881). Cover design, llustrations, and lettering by Wheeler.

Candace Wheeler, Prize Painting Book: Good Times (New York: White and Stokes, 1881). Illustrations and lettering by Wheeler.

Dora Wheeler, Illustrator. "Old Crummels: His Tale" (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1881).

Lucy Larcom, The Cross and the Grail (Chicago: Women's Temperance Pub'n Association: 1887). Illustrations and lettering by Wheeler.

Mary Mathews Barnes, Epithalamion (New York and London: Putnam's, 1889). Illustrations and lettering by Wheeler.

Annie Flint, Sunbeam Stories (New York: Bonnell, Silver, 1897). Illustrations by Wheeler Keith and others.

Candace Wheeler, Content in a Garden (New York: Houghton, Mifflin, 1901). Illustrated by Wheeler Keith.

Candace Wheeler, Double Darling and the Dream Spinner (New York: Fox, Duffield, 1905). Illustrations by Wheeler Keith.

Lilian Lida Bell, Carolina Lee (Boston, Page, 1906). Frontispiece by Wheeler Keith.

Annie Austin Flint, The Breaking Point: A Novel (New York: Broadway Publishing, 1916).

Notes

[edit]- ^ Weiss 2022, Chapter 3; Wheeler 1918, p. 130.

- ^ Peck & Irish 2001, p. 3.

- ^ Wheeler 1918, p. 72; Weiss 2022, Chapter 2; Peck & Irish 2001, p. 7.

- ^ Wheeler 1918, p. 234; Weiss 2022, Chapter 4.

- ^ Weiss 2022, Chapters 4 & 5.

- ^ Peck & Irish 2001, p. 17,18, 18.n.78.

- ^ Wheeler 1918, p. 208.

- ^ John Bonner; George William Curtis; Henry Mills Alden (1890). Harper's Weekly. Harper's Magazine Company. pp. 479–.

- ^ Weiss 2023a, Chapters 4 & 5.

- ^ "Portrait of Miss Dora Wheeler by William Merritt Chase". Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art. March 1922. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ Weiss 2023b, Chapters 6 & 7.

- ^ Peck & Irish 2001, p. 56, 81.

- ^ "NEW-YORK WOMAN AT THE FAIR . . . Mrs. Dora Wheeler Keith's Beautiful Painting on the Ceiling of the library of the Women's Building . ". The New York Times. 1893. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ Peck & Irish 2001, p. 11.

- ^ Wheeler 1918, p. 90.

- ^ Peck & Irish 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Weiss 2023a, Chapter 1.

- ^ Wheeler 1918, p. 245.

- ^ a b c d Weiss 2023a, Chapter 4.

- ^ Peck & Irish 2001, p. 175.

- ^ a b c d e f "Obituary, Dora Wheeler Keith" (PDF). Brooklyn Eagle. December 28, 1940. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ Peck & Irish 2001, p. 145.

- ^ Peck & Irish 2001, p. 169.

- ^ Peck & Irish 2001, pp. 171, 122.

- ^ Weiss 2023a, Chapter 4; Weiss 2023b, Chapter 5.

- ^ Weiss 2023a, Chapters 3 and 5; Weiss 2023b, Chapters 3 & 5.

- ^ a b Weiss 2023a, Chapter 5.

- ^ Wheeler 1918, p. 349.

- ^ a b Peck & Irish 2001, p. 47.

- ^ Peck & Irish 2001, p. 56.

- ^ a b c Weiss 2023b, Chapter 2.

- ^ a b c Peck & Irish 2001, p. 176.

- ^ Nichols, K. L. "Women's Art at the World's Columbian Fair & Exposition, Chicago 1893". Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- ^ Wheeler 1918, p. 253.

- ^ Peck & Irish 2001, p. 174, 175.

- ^ Wheeler 1918, p. 259.

- ^ Wheeler 1918, p. 253, 254.

- ^ a b Peck & Irish 2001.

- ^ John Singer Sargent (1890). "La Carmentica (exhibited at Metropolitan Museum of Art)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ^ Weiss 2023a, Chapters 2, 4 & 5.

- ^ Wheeler 1918, p. 24.

- ^ Wheeler 1914, p. 25.

- ^ Peck & Irish 2001, p. 13.

- ^ Susan Dominus (October 7, 2001). "Mother Interior". The New York Times. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

Today, only one [tapestry by] Dora Wheeler, survives intact. Poignantly, it shows Penelope, whose husband, Odysseus, is long gone, postponing her obligation to remarry by unraveling her own weaving -- an act of self-preservation, but also self-defeat.

- ^ "Dora Wheeler portraits listed in the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution". August 21, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

References

[edit]- Peck, Amelia; Irish, Carol (2001). Candace Wheeler: The Art and Enterprise of American Design. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. ISBN 1-58839-002-0.

- Weiss, Ila (2022). Candace Wheeler, A Creative Life: Book One, Genesis (1827-1876). Kindle Direct.

- Weiss, Ila (2023a). Candace Wheeler, A Creative Life: Book Two, Fruition (1886-1892). Kindle Direct.

- Weiss, Ila (2023b). Candace Wheeler, A Creative Life: Book Three, Bounty (1887-1923). Kindle Direct.

- Wheeler, Candace (1918). Yesterdays in a Busy Life. Harper Brothers, NY.

- Wheeler, Candace (1914). Annals of Onteora. privately printed, Erle W. Whitfield, N.Y., (special collections, University of Virginia Library).