François Arago

François Arago | |

|---|---|

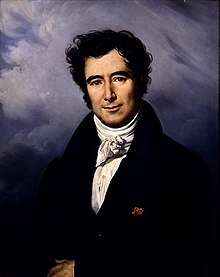

Portrait by Charles de Steuben | |

| President of the Executive Commission | |

| In office 9 May 1848 – 28 June 1848 | |

| Preceded by | Jacques-Charles Dupont de l'Eure (as President of the Provisional Government) |

| Succeeded by | Louis-Eugène Cavaignac (as Chief of the Executive Power) |

| Minister of War | |

| In office 5 April 1848 – 11 May 1848 | |

| President | Jacques-Charles Dupont de l'Eure |

| Preceded by | Louis-Eugène Cavaignac |

| Succeeded by | Jean-Baptiste-Adolphe Charras |

| Minister of the Navy | |

| In office 24 February 1848 – 4 May 1848 | |

| President | Jacques-Charles Dupont de l'Eure |

| Preceded by | Louis Napoléon Lannes |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Grégoire Casy |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 26 February 1786 Estagel, Roussillon, France |

| Died | 2 October 1853 (aged 67) Paris, Seine, France |

| Resting place | Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris |

| Political party | Moderate Republican |

| Spouse |

Lucie Carrier-Besombes

(m. 1811; died 1829) |

| Children | Emmanuel Arago Alfred Gabriel |

| Alma mater | École Polytechnique |

| Profession | Astronomer, physicist, mathematician |

| Known for | Rotary polarization Polarizer Eddy currents Fresnel–Arago laws Arago spot Arago's rotations Arago telescope |

| Awards | Copley Medal |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy, mathematics, physics |

| Institutions | Bureau des Longitudes, French Academy of Sciences, Paris Observatory |

| Patrons | Siméon Denis Poisson Pierre-Simon Laplace |

| Signature | |

| |

Dominique François Jean Arago (Catalan: Domènec Francesc Joan Aragó), known simply as François Arago (French: [fʁɑ̃swa aʁaɡo]; Catalan: Francesc Aragó, IPA: [fɾənˈsɛsk əɾəˈɣo]; 26 February 1786 – 2 October 1853), was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer, freemason,[1] supporter of the Carbonari revolutionaries[2] and politician.

Early life and work

[edit]Arago was born at Estagel, a small village of 3,000[3] near Perpignan, in the département of Pyrénées-Orientales, France, where his father held the position of Treasurer of the Mint. His parents were François Bonaventure Arago (1754–1814) and Marie Arago (1755–1845).

Arago was the eldest of four brothers. Jean (1788–1836) emigrated to North America and became a general in the Mexican army. Jacques Étienne Victor (1799–1855) took part in Louis de Freycinet's exploring voyage in the Uranie from 1817 to 1821, and on his return to France devoted himself to his journalism and the drama. The fourth brother, Étienne Vincent (1802–1892), is said to have collaborated with Honoré de Balzac in The Heiress of Birague, and from 1822 to 1847 wrote a great number of light dramatic pieces, mostly in collaboration.[4]

Showing decided military tastes, François Arago was sent to the municipal college of Perpignan, where he began to study mathematics in preparation for the entrance examination of the École Polytechnique. Within two years and a half he had mastered all the subjects prescribed for examination, and a great deal more, and, on going up for examination at Toulouse, he astounded his examiner by his knowledge of J.-L. Lagrange's work.[4][5]

Towards the close of 1803, Arago entered the École Polytechnique, Paris, but apparently found the professors there incapable of imparting knowledge or maintaining discipline. The artillery service was his ambition, and in 1804, through the advice and recommendation of Siméon Poisson, he received the appointment of secretary to the Paris Observatory. He now became acquainted with Pierre-Simon Laplace, and through his influence was commissioned, with Jean-Baptiste Biot, to complete the meridian arc measurements which had been begun by J. B. J. Delambre, and interrupted since the death of P. F. A. Méchain in 1804 (the meridian arc of Delambre and Méchain). Arago and Biot left Paris in 1806 and began operations along the mountains of Spain. Biot returned to Paris after they had determined the latitude of Formentera, the southernmost point to which they were to carry the survey.[4] Arago continued the work until 1809, his purpose being to measure a meridian arc in order to determine the exact length of a metre.

After Biot's departure, the political ferment caused by the entrance of the French into Spain extended to the Balearic Islands, and the population suspected Arago's movements and his lighting of fires on the top of Mount Galatzó (Catalan: Mola de l'Esclop) as the activities of a spy for the invading army.[5] Their reaction was such that he was obliged to give himself up for imprisonment in the fortress of Bellver in June 1808. On 28 July he escaped from the island in a fishing-boat, and after an adventurous voyage he reached Algiers on 3 August. From there he obtained a passage in a vessel bound for Marseille, but on 16 August, just as the vessel was nearing Marseille, it fell into the hands of a Spanish corsair. With the rest the crew, Arago was taken to Roses, and imprisoned first in a windmill, and afterwards in a fortress, until the town fell into the hands of the French, when the prisoners were transferred to Palamos.[4][5]

After three months' imprisonment, Arago and the others were released on the demand of the dey of Algiers, and again set sail for Marseille on 28 November, but then within sight of their port they were driven back by a northerly wind to Bougie on the coast of Africa. Transport to Algiers by sea from this place would have occasioned a weary delay of three months; Arago, therefore, set out over land, guided by a Muslim priest, and reached it on Christmas Day. After six months in Algiers he once again, on 21 June 1809, set sail for Marseille, where he had to undergo a monotonous and inhospitable quarantine in the lazaretto, before his difficulties were over. The first letter he received, while in the lazaretto, was from Alexander von Humboldt; and this was the origin of a connection which, in Arago's words, "lasted over forty years without a single cloud ever having troubled it."[4]

Scientific studies

[edit]Arago had succeeded in preserving the records of his survey; and his first act on his return home was to deposit them in the Bureau des Longitudes at Paris. As a reward for his adventurous conduct in the cause of science, he was elected a member of the French Academy of Sciences, at the remarkably early age of twenty-three, and before the close of 1809 he was chosen by the council of the École Polytechnique to succeed Gaspard Monge in the chair of analytical geometry. At the same time he was named by the emperor one of the astronomers of the Paris Observatory, which was accordingly his residence till his death. It was in this capacity that he delivered his remarkably successful series of popular lectures in astronomy, which were continued from 1812 to 1845.[4]

In 1818 or 1819 he proceeded along with Biot to execute geodetic operations on the coasts of France, England and Scotland. They measured the length of the seconds pendulum at Leith, Scotland, and in the Shetland Islands, the results of the observations being published in 1821, along with those made in Spain. Arago was elected a member of the Bureau des Longitudes immediately afterwards, and contributed to each of its Annuals, for about twenty-two years, important scientific notices on astronomy and meteorology and occasionally on civil engineering, as well as interesting memoirs of members of the Academy.[4]

Arago's earliest physical researches were on the pressure of steam at different temperatures, and the velocity of sound, 1818 to 1822. His magnetic observations mostly took place from 1823 to 1826. He discovered rotatory magnetism, what has been called Arago's rotations, and the fact that most bodies could be magnetized; these discoveries were completed and explained by Michael Faraday.

Arago warmly supported Augustin-Jean Fresnel's optical theories, helping to confirm Fresnel's wave theory of light by observing what is now known as the spot of Arago. The two philosophers conducted together those experiments on the polarization of light which led to the inference that the vibrations of the luminiferous ether were transverse to the direction of motion, and that polarization consisted of a resolution of rectilinear propagation into components at right angles to each other. The subsequent invention of the polariscope and discovery of Rotary polarization are due to Arago. He invented the first polarization filter in 1812.[6] He was the first to perform a polarimetric observation of a comet when he discovered polarized light from the tail of the Great Comet of 1819.[7]

The general idea of the experimental determination of the velocity of light in the manner subsequently effected by Hippolyte Fizeau and Léon Foucault was suggested by Arago in 1838, but his failing eyesight prevented his arranging the details or making the experiments.

Arago's fame as an experimenter and discoverer rests mainly on his contributions to magnetism in the co-discovery with Léon Foucault of eddy currents, and still more to optics. He showed that a magnetic needle, made to oscillate over nonferrous surfaces, such as water, glass, copper, etc., falls more rapidly in the extent of its oscillations according as it is more or less approached to the surface. This discovery, which earned him the Copley Medal of the Royal Society in 1825, was followed by another, that a rotating plate of copper tends to communicate its motion to a magnetic needle suspended over it, which he called "magnetism of rotation"[8][9][10] but (after Faraday's explanation of 1832[11]: 283 ) is now known as eddy current. Arago is also fairly entitled to be regarded as having proved the long-suspected connexion between the aurora borealis and the variations of the magnetic elements.[4] In 1827 he was elected an associated member of the Royal Institute of the Netherlands, when that institute became the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1851, he became foreign member.[12] In 1828, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

In optics, Arago not only made important optical discoveries on his own, but is credited with stimulating the genius of Jean-Augustin Fresnel, with whose history, as well as that of Étienne-Louis Malus and Thomas Young, this part of his life is closely interwoven.

Shortly after the beginning of the 19th century the labours of at least three philosophers were shaping the doctrine of the undulatory, or wave, theory of light. Fresnel's arguments in favour of that theory found little favour with Laplace, Poisson and Biot, the champions of the emission theory; but they were ardently espoused by Humboldt and by Arago, who had been appointed by the Academy to report on the paper.[4] This was the foundation of an intimate friendship between Arago and Fresnel, and of a determination to carry on together further fundamental laws of the polarization of light known by their means. As a result of this work, Arago constructed a polariscope, which he used for some interesting observations on the polarization of the light of the sky. He also discovered the power of rotatory polarization exhibited by quartz.[13]

Among Arago's many contributions to the support of the undulatory hypothesis, comes the experimentum crucis which he proposed to carry out for measuring directly the velocity of light in air and in water and glass. On the emission theory the velocity should be accelerated by an increase of density in the medium; on the wave theory, it should be retarded. In 1838 he communicated to the Academy the details of his apparatus, which utilized the relaying mirrors employed by Charles Wheatstone in 1835 for measuring the velocity of the electric discharge; but owing to the great care required in the carrying out of the project, and to the interruption to his labours caused by the revolution of 1848, it was the spring of 1850 before he was ready to put his idea to the test; and then his eyesight suddenly gave way. Before his death, however, the retardation of light in denser media was demonstrated by the experiments of H. L. Fizeau and B. L. Foucault, which, with improvements in detail, were based on the plan proposed by him.[4]

Politics and legacy

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2022) |

In 1830, Arago, who always professed liberal opinions of the republican type, was elected a member of the chamber of deputies for the Pyrénées-Orientales département, and he employed his talents of eloquence and scientific knowledge in all questions connected with public education, the rewards of inventors, and the encouragement of the mechanical and practical sciences. Many of the most creditable national enterprises, dating from this period, are due to his advocacy – such as the reward to Louis Daguerre for the invention of photography, the grant for the publication of the works of Fermat and Laplace, the acquisition of the museum of Cluny, the development of railways and electric telegraphs, the improvement of the reneile. In 1839, Arago reported the invention of photography to stunned listeners of a joint meeting of the academies of Arts and Sciences.

In 1830, Arago also was appointed director of the Observatory, and as a member of the chamber of deputies he was able to obtain grants of money for rebuilding it in part, and for the addition of magnificent instruments. In the same year, too, he was chosen perpetual secretary of the Academy of Sciences, the place of Joseph Fourier. Arago threw himself into its service, and by his faculty of making friends he gained at once for it and for himself a worldwide reputation. As perpetual secretary it was his duty to pronounce historical eulogies on deceased members; and for this duty his rapidity and facility of thought, and his happy piquancy of style, and his extensive knowledge peculiarly adapted him. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1832.[14]

In 1834, Arago again visited Scotland, to attend the meeting of the British Association at Edinburgh. From this time till 1848 he led a life of comparative quiet – although he continued to work within the Academy and the Observatory to produce a multitude of contributions to all departments of physical science – but on the fall of Louis-Philippe he left his laboratory to join the Provisional Government (24 February 1848). He was entrusted with two important functions, that had never before been given to one person, viz. the ministry of marine and colonies (24 February 1848 – 11 May 1848) and ministry of war (5 April 1848 – 11 May 1848); in the former capacity he improved rations in the navy and abolished flogging. He also abolished political oaths of all kinds and, against an array of moneyed interests, succeeded in procuring the abolition of slavery in the French colonies.

On 10 May 1848, Arago was elected a member of the Executive Power Commission, a governing body of the French Republic. He was made President of the Executive Power Commission (11 May 1848) and served in this capacity as provisional head of state until 24 June 1848, when collective resignation of the commission was submitted to the National Constituent Assembly. At the beginning of May 1852, when the government of Louis Napoleon required an oath of allegiance from all its functionaries, Arago peremptorily refused, and sent in his resignation of his post as astronomer at the Bureau des Longitudes. This, however, the prince president declined to accept, and made "an exception in favour of a savant whose works had thrown lustre on France, and whose existence the government would regret to embitter."

Cape Gregory in Oregon was named by Captain Cook on 12 March 1778 after Saint Gregory, the saint of that day; it was renamed Cape Arago after François Arago.[15]

Last years

[edit]Arago remained a consistent republican to the end, and after the coup d'état of 1852, though suffering first from diabetes, then from Bright's disease, complicated by dropsy, he resigned his post as astronomer rather than take the oath of allegiance. Napoleon III gave directions that the old man should be in no way disturbed, and should be left free to say and do what he liked. In the summer of 1853 Arago was advised by his physicians to try the effect of his native air, and he accordingly set out to the eastern Pyrenees, but this was ineffective and he died in Paris. His grave is at the famous Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Arago was an atheist.[16]

Named after Arago

[edit]

- The study association for Applied Physics at the University of Twente was named after Arago.

- His name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

- The outer main-belt asteroid 1005 Arago, an inner ring of Neptune, the lunar crater Arago as well as the Martian crater Arago were also named in his honor.[17]

- Two French cable ships were named after him, the François Arago of 1882 and the Arago of 1914/1931.

Honours

[edit] Kingdom of Belgium: Officer of the Order of Leopold.[18]

Kingdom of Belgium: Officer of the Order of Leopold.[18]- 1842 Prussian Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts.[19]

Publications

[edit]

Arago's works were published after his death under the direction J. A. Barral, in 17 vols., 8vo, 1854–1862 (F. Arago (1854), Jean-Augustin Barral (ed.), Œuvres complètes de Francois Arago (in French), Paris, Leipzig: Gide et J. Baudry, doi:10.5962/BHL.TITLE.20983, Wikidata Q51430135); also separately his Astronomie populaire, in 4 vols.; Notices biographiques, in 3 vols.; Indices scientifiques, in 5 vols.; Voyages scientifiques, in 1 vol.; Grimoires scientifiques, in 2 vols.; Mélanges, in I vol.; and Tables analytiques et documents importants (with portrait), in 1 vol.

English translations of the following portions of Arago's works have appeared:

- Treatise on Comets, by C. Gold, C.B. (London, 1833); also translated W. H. Smyth and Grant (London, 1861)

- Euloge of James Watt, by Muirhead (London, 1839); also translated, with notes, by Brougham

- Popular Lectures on Astronomy, by Walter Kelly and Rev. L. Tomlinson (London, 1854); also translated by Dr W. H. Smyth and Prof. R. Grant, 2 vols. (London, 1855)

- Arago's Autography, translated by the Rev. Baden Powell (London, 1855, 58)

- Arago's Meteorological Essays, with introduction by Alexander von Humboldt, translated under the supervision of Colonel Edward Sabine (London, 1855)

- François Arago; et al. (1859), Biographies of distinguished scientific men, Boston: Ticknor and Fields, doi:10.5962/BHL.TITLE.19132, Wikidata Q51427133

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Victor SCHOELCHER Républicain et franc-maçon, Anne GIROLLET, ed. Maçonnique Française, p. 26

- ^ Dictionnaire universel de la Franc-Maçonnerie By Monique Cara, Jean-Marc Cara, Marc Jode

- ^ "Francois Arago". The Canadian Journal. 2: 159. 1854. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Arago, Dominique François Jean". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 312–313.

- ^ a b c F. Arago (1859), The history of my youth, Boston: Ticknor and Fields, doi:10.5962/BHL.TITLE.19132, Wikidata Q51427133

- ^ Hellemans, Alexander; Bunch, Bryan (1988). The Timetables of Science. Simon & Schuster. p. 261. ISBN 0671621300.

- ^ Kolokolova, Ludmilla (2015). Polarimetry of Stars and Planetary Systems. Cambridge University Press. p. 380. ISBN 978-1-107-04390-9.

- ^ Annales de chimie et de physique (1824), vol. 27, page 363: "M. Arago communique verbalement les résultats de quelques expériences qu'il a faites sur l'influence que les métaux et beaucoup d'autres substances exercent sur l'aiguille aimantée, et qui a pour effet de diminuer rapidement l'amplitude des oscillations sans altérer sensiblement leur durée. Il promet, à ce sujet, un Mémoire détaillé." (Mr. Arago orally communicates the results of some experiments that he has conducted on the influence that metals and many other substances exert on a magnetic needle, which has the effect of rapidly reducing the amplitude of the oscillations without altering significantly their duration. He promises, on this subject, a detailed memoir.)

- ^ Arago (1826). ""Note concernant les Phénomènes magnétiques auxquels le mouvement donne naissance" (Note concerning magnetic phenomena that motion creates)". Annales de chimie et de physique. 32: 213–223.

- ^ Babbage, C.; Herschel, J.W.F. (1825). "Account of the repetition of M. Arago's experiments on the magnetism manifested by various substances during the act of rotation". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 115: 467–496. Bibcode:1825RSPT..115..467B. doi:10.1098/rstl.1825.0023.

- ^ Philosospical magazine 1840

- ^ "Dominique François Jean Arago (1786–1853)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Arago (1811) "Mémoire sur une modification remarquable qu'éprouvent les rayons lumineux dans leur passage à travers certains corps diaphanes et sur quelques autres nouveaux phénomènes d'optique" (Memoir on a remarkable modification that light rays experience during their passage through certain translucent substances and on some other new optical phenomena), Mémoires de la classe des sciences mathématiques et physiques de l'Institut Impérial de France, 1st part : 93–134.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter A" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ McArthur, Lewis A.; McArthur, Lewis L. (2003) [1928]. Oregon Geographic Names (7th ed.). Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0875952772.

- ^ "The same Arago who spent his time criticizing unfounded myths now peddled them. Arago the atheist now spoke of souls." Theresa Levitt, The shadow of enlightenment: optical and political transparency in France, 1789–1848, page 105.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2012). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 139. ISBN 978-3-642-29718-2.

- ^ Almanach royal officiel de Belgique/1841 p118

- ^ Orden Pour le Mérite für Wissenschaften und Künste (1975). Die Mitglieder des Ordens. 1 1842-1881 (PDF). Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag. p. 2. ISBN 3-7861-6189-5.

Further reading

[edit]- F. Arago (1859), The history of my youth, Boston: Ticknor and Fields, doi:10.5962/BHL.TITLE.19132, Wikidata Q51427133

- Hahn, Roger (1970). "Arago, Dominique François Jean". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 200–203. ISBN 0-684-10114-9.

- Lequeux, James (2008), François Arago, un savant généreux, Paris: EDP-Sciences, ISBN 978-2-86883-999-2

- Walter Baily, A Mode of producing Arago's Rotation. 28 June 1879. (Philosophical magazine: a journal of theoretical, experimental and applied physics. Taylor & Francis., 1879)

External links

[edit]- Works by François Arago at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about François Arago at the Internet Archive

- Works by François Arago at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Obituary Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 1854, volume 14, page 102

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "François Arago", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- The 0 meridian in Paris misused in The Da Vinci Code is in fact an art project by the Dutch artist Jan Dibbets (1941) made in 1987 as a tribute to the astronomer François Arago (1786–1853)

- S.V. Arago The study association for applied physics (Dutch) at the University of Twente is named after François Arago.

- Portrait of Francois F. Arago from the Lick Observatory Records Digital Archive, UC Santa Cruz Library's Digital Collections Archived 27 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- « Arago et l’Observatoire de Paris », Virtual exhibition on Paris Observatory digital library

- 1786 births

- 1853 deaths

- 19th-century heads of state of France

- People from Pyrénées-Orientales

- Politicians from Occitania (administrative region)

- Moderate Republicans (France)

- Heads of state of France

- Ministers of war of France

- Ministers of marine and the colonies

- Members of the 2nd Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy

- Members of the 3rd Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy

- Members of the 4th Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy

- Members of the 5th Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy

- Members of the 6th Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy

- Members of the 7th Chamber of Deputies of the July Monarchy

- Members of the 1848 Constituent Assembly

- Members of the National Legislative Assembly of the French Second Republic

- 19th-century French mathematicians

- Scientists from Catalonia

- 19th-century French astronomers

- French atheists

- French Freemasons

- 19th-century French physicists

- Vision scientists

- French people of the Revolutions of 1848

- École Polytechnique alumni

- Members of the French Academy of Sciences

- Honorary Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- Honorary members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences

- Members of the Royal Academy of Belgium

- Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- Officers of the French Academy of Sciences

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Foreign members of the Royal Society

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)

- Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery

- 18th-century atheists

- 19th-century atheists

- Members of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities