Passiflora

| Passiflora | |

|---|---|

| |

| Passiflora incarnata | |

| |

| P. quadrangularis unripe fruit | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malpighiales |

| Family: | Passifloraceae |

| Subfamily: | Passifloroideae |

| Tribe: | Passifloreae |

| Genus: | Passiflora L. |

| Type species | |

| Passiflora incarnata L.[1] | |

| Species | |

|

About 550, see list | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

List

| |

Passiflora, known also as the passion flowers or passion vines, is a genus of about 550 species of flowering plants, the type genus of the family Passifloraceae.

Description

[edit]They are mostly tendril-bearing vines, with some being shrubs or trees. They can be woody or herbaceous.[3]

Passion flowers produce regular and usually showy flowers with a distinctive corona. There can be as many as eight concentric coronal series, as in the case of P. xiikzodz.[3] The flower is pentamerous (except for a few Southeast Asian species) and ripens into an indehiscent fruit with numerous seeds.

The fruit ranges from 5–20 centimetres (2–8 in) long and 2.5–5 cm (1–2 in) across, depending upon the species or cultivar.

Chemistry

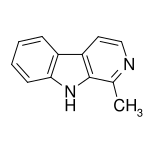

[edit]Many species of Passiflora have been found to contain beta-carboline harmala alkaloids,[4][5][6] some of which are MAO inhibitors. The flower and fruit have only traces of these chemicals, but the leaves and the roots often contain more.[6] The most common of these alkaloids is harman, but harmaline, harmalol, harmine, and harmol are also present.[4][5] The species known to bear such alkaloids include: P. actinia, P. alata (winged-stem passion flower), P. alba, P. bryonioides (cupped passion flower), P. caerulea (blue passion flower), P. capsularis, P. decaisneana, P. edulis (passion fruit), P. eichleriana, P. foetida (stinking passion flower), P. incarnata (maypop), P. quadrangularis (giant granadilla), P. suberosa, P. subpeltata and P. warmingii.[5]

Other compounds found in passion flowers are coumarins (e.g. scopoletin and umbelliferone), maltol, phytosterols (e.g. lutenin) and cyanogenic glycosides (e.g. gynocardin) which render some species, i.e. P. adenopoda, somewhat poisonous. Many flavonoids and their glycosides have been found in Passiflora, including apigenin, benzoflavone, homoorientin, 7-isoorientin, isoshaftoside, isovitexin (or saponaretin), kaempferol, lucenin, luteolin, n-orientin, passiflorine (named after the genus), quercetin, rutin, saponarin, shaftoside, vicenin and vitexin. Maypop, blue passion flower (P. caerulea), and perhaps others contain the flavone chrysin. Also documented to occur at least in some Passiflora in quantity are the hydrocarbon nonacosane and the anthocyanidin pelargonidin-3-diglycoside.[4][5][7]

The genus is rich in organic acids including formic, butyric, linoleic, linolenic, malic, myristic, oleic and palmitic acids as well as phenolic compounds, and the amino acid α-alanine. Esters like ethyl butyrate, ethyl caproate, n-hexyl butyrate and n-hexyl caproate give the fruits their flavor and appetizing smell. Sugars, contained mainly in the fruit, are most significantly d-fructose, d-glucose and raffinose. Among enzymes, Passiflora was found to be rich in catalase, pectin methylesterase and phenolase.[4][5]

Taxonomy

[edit]Passiflora is the most species rich genus of both the family Passifloraceae and the tribe Passifloreae. With over 550 species, an extensive hierarchy of infrageneric ranks is required to represent the relationships of the species. The infrageneric classification of Passiflora not only uses the widely used ranks of subgenus, section and series, but also the rank of supersection.

The New World species of Passiflora were first divided among 22 subgenera by Killip (1938) in the first monograph of the genus.[8] More recent work has reduced these to 4, which are commonly accepted today (in order from most basally to most recently branching):[9]

- Astrophea (Americas, ~60 species), trees and shrubs with simple, unlobed leaves

- Passiflora (Americas, ~250 species), woody vines with large flowers and elaborate corolla

- Deidamioides (Americas, 13 species), woody or herbaceous vines

- Decaloba (Americas, Asia and Australasia, ~230 species), herbaceous vines with palmately veined leaves

Some studies have shown that the segregate Old World genera Hollrungia and Tetrapathaea are nested within Passiflora, and form a fifth subgenus (Tetrapathaea).[10] Other studies support the current four subgenus classification.[11]

Relationships below the subgenus level are not known with certainty and are an active area of research. The Old World species form two clades – supersection Disemma (part of subgenus Decaloba) and subgenus Tetrapathaea. The former is composed of 21 species divided into sections Disemma (three Australian species), Holrungiella (one New Guinean species) and Octandranthus (seventeen south and east Asian species).[12]

The remaining (New World) species of subgenus Decaloba are divided into seven supersections. Supersection Pterosperma includes four species from Central America and southern Mexico. Supersection Hahniopathanthus includes five species from Central America, Mexico and northernmost South America. Supersection Cicea includes nineteen species, with apetalous flowers. Supersection Bryonioides includes twenty-one species, with a distribution centered on Mexico. Supersection Auriculata includes eight species from South America, one of which is also found in Central America. Supersection Multiflora includes nineteen species. Supersection Decaloba includes 123 species.[13]

Distribution

[edit]Passiflora has a largely neotropic distribution, unlike other genera in the family Passifloraceae, which includes more Old World species (such as the genus Adenia). The vast majority of Passiflora are found in Mexico, Central America, the United States and South America, although there are additional representatives in Southeast Asia and Oceania.[14] New species continue to be identified: for example, P. xishuangbannaensis and P. pardifolia have only been known to the scientific community since 2005 and 2006, respectively.

Some species of Passiflora have been naturalized beyond their native ranges. For example, the blue passion flower (P. caerulea) now grows wild in Spain.[15] The purple passionfruit (P. edulis) and its yellow relative flavicarpa have been introduced in many tropical regions as commercial crops.

Ecology

[edit]Passion flowers have floral structures adapted for biotic pollination. Pollinators of Passiflora include bumblebees, carpenter bees (e.g., Xylocopa sonorina), wasps, bats, and hummingbirds (especially hermits such as Phaethornis); some others are additionally capable of self-pollination. Passiflora often exhibit high levels of pollinator specificity, which has led to frequent coevolution across the genus. The sword-billed hummingbird (Ensifera ensifera) is a notable example: it, with its immensely elongated bill, is the sole pollinator of 37 species of high Andean Passiflora in the supersection Tacsonia.[16]

The leaves are used for feeding by the larvae of a number of species of Lepidoptera. Famously, they are exclusively targeted by many butterfly species of the tribe Heliconiini. The many defensive adaptations visible on Passiflora include diverse leaf shapes (which help disguise their identity), colored nubs (which mimic butterfly eggs and can deter Heliconians from ovipositing on a seemingly crowded leaf), extrafloral nectaries, trichomes, variegation, and chemical defenses.[17] These, combined with adaptations on the part of the butterflies, were important in the foundation of coevolutionary theory.[18][19]

Recent studies have shown that passiflora both grow faster and protect themselves better in high-nitrogen soils. In low-nitrogen environments, passiflora focus on growth rather than defense and are more vulnerable to herbivores.[20]

The following lepidoptera larvae are known to feed on Passiflora:

- Longwing butterflies (Heliconiinae)

- Cydno longwing (Heliconius cydno), one of few Heliconians to feed on multiple species of Passiflora[21]

- Gulf fritillary (Agraulis vanillae), which feeds on several species of Passiflora, such as Passiflora lutea, Passiflora affinis,[22][23] stinking passion flower (P. foetida),[24] and Maypop (P. incarnata)

- American Sara longwing (Heliconius sara)

- Red postman (Heliconius erato)

- Asian leopard lacewing (Cethosia cyane)

- Postman butterfly (Heliconius melpomene) prefer P. menispermifolia and P. oerstedii

- Zebra longwing (Heliconius charithonia) feed on yellow passion flower, two-flowered passion flower (P. biflora), and corky-stemmed passion flower (P. suberosa).

- Banded orange (Dryadula phaetusa) feed on P. tetrastylis.

- Julia butterfly (Dryas iulia) feed on yellow passion flower and P. affinis.

- Swift moth Cibyra serta

- Tawny Coster (Acraea terpsicore) feed on Passiflora edulis,[25] Passiflora foetida[25] and Passiflora subpeltata[25]

The generally high pollinator and parasite specificity in Passiflora may have led to the tremendous morphological variation in the genus. It is thought to have among the highest foliar diversity among all plant genera,[8] with leaf shapes ranging from unlobed to five-lobed frequently found on the same plant.[26] Coevolution can be a major driver of speciation, and may be responsible for the radiation of certain clades of Passiflora such as Tacsonia.

The bracts of the stinking passion flower are covered by hairs which exude a sticky fluid. Many small insects get stuck to this and get digested to nutrient-rich goo by proteases and acid phosphatases. Since the insects usually killed are rarely major pests, this passion flower seems to be a protocarnivorous plant.[27]

Banana passion flower or "banana poka" (P. tarminiana), originally from Central Brazil, is an invasive weed, especially on the islands of Hawaii. It is commonly spread by feral pigs eating the fruits. It overgrows and smothers stands of endemic vegetation, mainly on roadsides. Blue passion flower (P. caerulea) is an invasive species in Spain and considered likely to threaten ecosystems there.[15]

On the other hand, some species are endangered due to unsustainable logging and other forms of habitat destruction. For example, the Chilean passion flower (P. pinnatistipula) is a rare vine growing in the Tropical Andes southwards from Venezuela between 2,500 and 3,800 metres (8,200 and 12,500 ft) in altitude, and in Coastal Central Chile, where it only occurs in a few tens of square kilometres of fog forest by the sea, near Zapallar. P. pinnatistipula has a round fruit, unusual in Tacsonia group species like banana passion flower and P. mixta, with their elongated tubes and brightly red to rose-colored petals.[citation needed]

Notable and sometimes economically significant pathogens of Passiflora are several sac fungi of the genus Septoria (including S. passiflorae), the undescribed proteobacterium called "Pseudomonas tomato" (pv. passiflorae), the Potyvirus passionfruit woodiness virus, and the Carlavirus Passiflora latent virus.

Adverse effects

[edit]Passion flower is not recommended during pregnancy because it may induce contractions.[28][4] Consuming passion flower products may cause drowsiness, nausea, dizziness, abnormal heart rhythms, asthma, or rhinitis.[28][4]

Uses

[edit]Ornamental

[edit]

A number of species of Passiflora are cultivated outside their natural range for both their flowers and fruit. Hundreds of hybrids have been named; hybridizing is currently being done extensively for flowers, foliage and fruit. The following hybrids and cultivars have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit:

- 'Amethyst'[29]

- P. × exoniensis[30] (Exeter passion flower)

- P. × violacea[31]

During the Victorian era the flower (which in all but a few species lasts only one day) was very popular, and many hybrids were created using the winged-stem passion flower (P. alata), the blue passion flower (P. caerulea) and other tropical species.

Many cool-growing Passiflora from the Andes Mountains can be grown successfully for their beautiful flowers and fruit in cooler Mediterranean climates, such as the Monterey Bay and San Francisco in California and along the western coast of the U.S. into Canada. One blue passion flower or hybrid even grew to large size at Malmö Central Station in Sweden.[32]

Passion flowers have been a subject of studies investigating extranuclear inheritance; paternal inheritance of chloroplast DNA has been documented in this genus.[33] The plastome of the two-flowered passion flower (P. biflora) has been sequenced.

Fruit

[edit]

Most species have round or elongated edible fruit.

- The passion fruit or maracujá (P. edulis) is cultivated extensively in the Caribbean, South America, south Florida and South Africa for its fruit, which is used as a source of juice. A small pink fruit that wrinkles easily and a larger shiny yellow to orange fruit are traded under this name. The latter is usually considered just a variety of flavicarpa, but seems to be more distinct.[citation needed]

- Sweet granadilla (P. ligularis) is another widely grown species. In large parts of Africa and Australia it is the plant called "passionfruit": confusingly, in South African English the latter species is more often called granadilla (without an adjective). Its fruit is somewhat intermediate between the two sold as P. edulis.

- Maypop (P. incarnata), a common species in the southeastern US. This is a subtropical representative of this mostly tropical family. However, unlike the more tropical cousins, this particular species is hardy enough to withstand the cold down to −20 °C (−4 °F) before its roots die (it is native as far north as Pennsylvania and has been cultivated as far north as Boston and Chicago.) The fruit is sweet, yellowish, and roughly the size of a chicken's egg; it enjoys some popularity as a native plant with edible fruit and few pests.

- Giant granadilla (giant tumbo or badea, P. quadrangularis), water lemon (P.laurifolia) and sweet calabash (P. maliformis) are Passiflora species locally famed for their fruit,[34] but not widely known elsewhere as of 2008[update].[citation needed]

- The blue passionflower (Passiflora caerulea) produces bright orange fruit with numerous seeds. While the fruit is edible, it is often described as being bland in comparison to other edible passionfruit, or with a flavour vaguely similar to blackberries.[35]

- Wild maracuja are the fruit of P. foetida, which are popular in Southeast Asia.

- Banana passionfruits are the very elongated fruits of P. tripartita var. mollissima and P. tarminiana. These are locally eaten, but their invasive properties make them a poor choice to grow outside of their native range.[36][37]

Ayahuasca analog

[edit]A native source of beta-Carbolines (e.g., passion flower in North America) is mixed with Desmanthus illinoensis (Illinois bundleflower) root bark to produce a hallucinogenic drink called prairiehuasca, which is an analog of the shamanic brew ayahuasca.[38]

Traditional medicine and dietary supplement

[edit]Passiflora incarnata (maypop) leaves and roots have a long history of use as a traditional medicine by Native Americans in North America and were adapted by European colonists.[28][4] The fresh or dried leaves of maypop are used to make a tea that is used as a sedative.[28] Passionflower as dried powder or an extract is used as a dietary supplement.[28] There is insufficient clinical evidence for using passionflower to treat any medical condition.[28][4]

Passionflower is classified as generally recognized as safe for use as a food ingredient in the U.S.[39]

In culture

[edit]

The passion in passion flower purportedly refers to the passion of Jesus in Christian theology;[40] the word passion comes from the Latin passio, meaning 'suffering'. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Spanish Christian missionaries adopted the unique physical structures of this plant, particularly the numbers of its various flower parts, as symbols of the last days of Jesus and especially his crucifixion:[41]

- The pointed tips of the leaves were taken to represent the Holy Lance.

- The tendrils represent the whips used in the flagellation of Christ.

- The ten petals and sepals represent the ten faithful apostles (excluding St. Peter, who denied Jesus three times, and Judas Iscariot, who betrayed him).

- The flower's radial filaments, which can number more than a hundred and vary from flower to flower, represent the crown of thorns.

- The chalice-shaped ovary with its receptacle represents the Holy Grail.

- The three stigmas represent three nails and the five anthers below them five hammers or five wounds (four by the nails and one by the lance).

- The blue and white colors of many species' flowers represent Heaven and Purity.

- In addition, the flower is open for three days, symbolising the three years of Jesus' ministry.[42]

The flower has been given names related to this symbolism throughout Europe since the 15th century. In Spain, it is known as espina de Cristo ('thorn of Christ'). Older Germanic names[43] include Christus-Krone ('Christ's crown'), Christus-Strauss ('Christ's bouquet'),[44] Dorn-Krone ('crown of thorns'), Jesus-Lijden ('Jesus' passion'), Marter ('passion')[45] or Muttergottes-Stern ('Mother of God's star').[46]

Outside the Roman Catholic heartland, the regularly shaped flowers have reminded people of the face of a clock. In Israel they are known as "clock-flower" (שעונית) and in Greece as "clock plant" (ρολογιά); in Japan too, they are known as tokeisō (時計草, 'clock plant'). In Hawaiian, they are called lilikoʻi;[47] lī is a string used for tying fabric together, such as a shoelace, and liko means 'to spring forth leave'.[48]

In India, it is known as Krishnakamala because of its dark violet blue colour which resembles Bhagwan Krishna.

Gallery

[edit]-

Bud of the passion flower

-

Passiflora 'Incense', a hybrid of the Brazilian species P. cincinnata and the American species P. incarnata

-

Passiflora caerulea 'Clear Sky', a tetraploid selection of P. caerulea

-

Passion flower bloom in water

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Passiflora | International Plant Names Index. (n.d.). Retrieved January 8, 2024, from https://www.ipni.org/n/328300-2

- ^ "Passiflora L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ a b Ulmer, Torsten; McDougal, John M. (2004). Passiflora - Passion Flowers of the World. Portland: Timber Press. pp. 158–159.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Passion flower". Drugs.com. 1 July 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Duke (2008)

- ^ a b Jim Meuninck (2008). Medicinal Plants of North America: A Field Guide. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1461745815.

- ^ Dhawan, et al. (2002)

- ^ a b Killip, E.P. (1938). The American Species of Passifloraceae. Chicago, US: Field Museum of Natural History.

- ^ Feuillet, C.; MacDougal, J. (2004). "A new infrageneric classification of Passiflora L. (Passifloraceae)". Passiflora. 13 (2): 34–35, 37–38.

- ^ Krosnick, S.E.; Ford, A.J.; Freudenstein, J.V. (2009). "Taxonomic Revision of Passiflora Subgenus Tetrapathea Including the Monotypic Genera Hollrungia and Tetrapathea (Passifloraceae), and a New Species of Passiflora". Systematic Botany. 34 (2): 375–385. doi:10.1600/036364409788606343. S2CID 86038282.

- ^ Hansen, K.A.; Gilbert, L.E.; Simpson, B.B.; Downie, S.R.; Cervi, A.C.; Jansen, R.K. (2006). "Phylogenetic Relationships and Chromosome Number Evolution in Passiflora". Systematic Botany. 31 (1): 138–150. doi:10.1600/036364406775971769. S2CID 4820527.

- ^ Shawn Elizabeth Krosnick, PhD thesis, Phylogenetic relationships and patterns of morphological evolution in the Old Word species of Passiflora (subgenus Decaloba: supersection Disemma and subgenus Tetrapathaea) Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "MBG: Research: Passiflora Research Network". mobot.org.

- ^ Krosnick, S.E.; Porter-Utley, K.E.; MacDougal, J.M.; Jørgensen, P.M.; McDade, L.A. (2013). "New insights into the evolution of Passiflora subgenus Decaloba (Passifloraceae): phylogenetic relationships and morphological synapomorphies". Systematic Botany. 38 (3): 692–713. doi:10.1600/036364413x670359. S2CID 85840835.

- ^ a b Sanz-Elorza, M.; Dana, E.; Sobrino, E. (2001). "Listado de plantas alóctonas invasoras reales y potenciales en España". Lazaroa. 22. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ Abrahamczyk, S. (2014). "Escape from extreme specialization: passionflowers, bats and the sword-billed hummingbird". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 281 (1795): 20140888. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0888. PMC 4213610. PMID 25274372.

- ^ de Castro, É.C.P.; Zagrobelny, M.; Cardoso, M.Z.; Bak, S. (2017). "The arms race between heliconiine butterflies and Passiflora plants - new insights on an ancient subject". Biological Reviews. 93 (1): 555–573. doi:10.1111/brv.12357. PMID 28901723. S2CID 23953807.

- ^ Ehrlich, P.R.; Raven, P.H. (1964). "Butterflies and Plants: A Study in Coevolution". Evolution. 18 (4): 586–608. doi:10.2307/2406212. JSTOR 2406212.

- ^ Benson, W.W; Brown, K.S.; Gilbert, L.E. (1975). "Coevolution of plants and herbivores: passion flower butterflies". Evolution. 29 (4): 659–680. doi:10.2307/2407076. JSTOR 2407076. PMID 28563089.

- ^ Morrison, Colin R.; Hart, Lauren; Wolf, Amelia A.; Sedio, Brian E.; Armstrong, Wyatt; Gilbert, Lawrence E. (3 March 2024). "Growth-chemical defence-metabolomic expression trade-off is relaxed as soil nutrient availability increases for a tropical passion vine". Functional Ecology. 38 (5): 1320–1337. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.14537. ISSN 0269-8463.

- ^ Merrill, R.M.; Naisbit, R.E.; Mallet, J.; Jiggins, C.D. (2013). "Ecological and genetic factors influencing the transition between host-use strategies in sympatric Heliconius butterflies" (PDF). Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 26 (9): 1959–1967. doi:10.1111/jeb.12194. PMID 23961921. S2CID 11632731.

- ^ Knight, R.J.; Payne, J.A.; Schnell, R.J.; Amis, A.A. (1995). "'Byron Beauty', An Ornamental Passion Vine for the Temperate Zone" (PDF). HortScience. 30 (5): 1112. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI.30.5.1112.

- ^ Neck, Raymond W. (1976). "Lepidopteran Foodplant Records from Texas" (PDF). The Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera. 15 (2): 75–82. doi:10.5962/p.333709. S2CID 248733989. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ^ Soule, J.A. 2012. Butterfly Gardening in Southern Arizona. Tierra del Soule Press, Tucson, AZ

- ^ a b c Nitin, Ravikanthachari; Balakrishnan, V. C.; Churi, Paresh V.; Kalesh, S.; Prakash, Satya; Kunte, Krushnamegh (10 April 2018). "Larval host plants of the butterflies of the Western Ghats, India". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 10 (4): 11495. doi:10.11609/jott.3104.10.4.11495-11550. ISSN 0974-7907.

- ^ Chitwood, D.; Otoni, W. (2017). "Divergent leaf shapes among Passiflora species arise from a shared juvenile morphology". Plant Direct. 1 (5): e00028. doi:10.1002/pld3.28. PMC 6508542. PMID 31245674.

- ^ Radhamani et al. (1995)

- ^ a b c d e f "Passionflower". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, US National Institutes of Health. 1 September 2016. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Passiflora 'Amethyst' AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Passiflora × exoniensis AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Passiflora × violacea AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Petersen (1966)

- ^ E.g. Hansen et al. (2006)

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 336.

- ^ "Passiflora caerulea (Blue Passion Flower)". Gardenia.net. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Smith, Clifford W. "Impact of Alien Plants on Hawai'i's Native Biota". University of Hawaii. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ The University of Georgia - Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health and the National Park Service (17 February 2011). "Invasive Plant Atlas of the United States". Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ Hegnauer, R.; Hegnauer, M. (1996). Caesalpinioideae und Mimosoideae Volume 1 Part 2. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 199. ISBN 9783764351656.

- ^ "Permitted Flavoring Agents and Related Substances; In: Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21". US Food and Drug Administration. 1 April 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ Kostka, Arun Oswin. "Flowers in Christian Symbolism".

- ^ Roger L. Hammer (6 January 2015). Everglades Wildflowers: A Field Guide to Wildflowers of the Historic Everglades, including Big Cypress, Corkscrew, and Fakahatchee Swamps. Falcon Guides. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-1-4930-1459-0.

- ^ Brewer, Ebenezer Cobham. The Wordsworth Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (2001 ed.). Wordsworth Reference. p. 826.

- ^ Marzell (1927)

- ^ "Christ's flower" is a mistranslation of Marzell (1927)

- ^ "Martyr" is a mistranslation of Marzell (1927)

- ^ Muttergottes-Schuzchen (or -Schurzchen) is a nonsensical misreading of Marzell (1927)

- ^ Mary Kawena Pukui; Samuel Hoyt Elbert (2003). "lookup of lilikoʻi". in Hawaiian Dictionary. Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaii Press. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ Pukui et al. (1992)

External links

[edit]- "Passiflora" at the Encyclopedia of Life

- The Passiflora Society International

- Killip, The American Species of Passifloraceae, Fieldiana, Bot. 19 (1938)

- Passiflora online

- Passiflora edulis Archived 5 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Passiflora Picture Gallery

- Chilean Passiflora pictures

- A list of Heliconius Butterflies and the Passiflora species their larvae consume