Differentiated integration

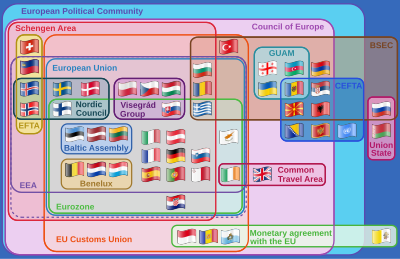

Differentiated integration (DI) is a mechanism that gives countries the possibility to opt out of certain European Union policies while other countries can further engage and adopt them. This mechanism theoretically encourages the process of European integration. It prevents policies that may be in the interest of most states to get blocked or only get adopted in a weaker form.[1] As a result, policies are not implemented uniformly in the EU. In some definitions of differentiated integration, it is legally codified in EU acts and treaties, through the enhanced cooperation procedure, but it can also be the result of treaties which have been agreed to externally to the EU's framework, for example in the case of the Schengen Agreement.[2]

Types of differentiated integration

[edit]In an attempt to resolve confusion around the many kinds of differentiated integration, Alexander Stubb categorised the mechanism into three distinct concepts: multi-speed, variable geometry, and à la carte. Each is respectively pegged to a corresponding variable: time, space, and matter.[3][4]

- In multi-speed DI, objectives are carried by a core group of states who are willing and able to achieve them.[5] Member states who cannot achieve them in the short term are expected to fulfill those same goals at a later time. This approach is supranational in nature. It assumes a clear integrative direction by default for all participating states with the differentiation being time.

- Variable geometry has a less integrative outlook. It starts with the assumption that European states are so different from one another that most common objectives are unattainable. Irreversible separation from one state to another in the process of integration is therefore accepted and permitted, the differentiation here being space. The expected result of this approach is a solid core of states who have gone far in the integration process with peripheral states who have engaged much less in integration.

- In À La Carte DI, states can choose the policy area they wish to participate in. The matter variable in this context refers to policy areas. This approach is fundamentally intergovernmental in nature.[3]

Stubb's initial work can be considered outdated as it does not take into account facets of DI which have more recently been outlined by academics.[6] Some academic literature includes de facto differentiated integration and informal opt-outs focusing on the different ways member states comply with uniform EU rules,[7] others look at groups of member states forming informal differentiated cooperation.[8] Two kinds of differentiated integration can separated: firstly, internal referring to the level of participation of EU members in implementing policies, and secondly, external which looks at the participation of non-member states in implementing EU policies. Furthermore, one can also distinguish horizontal to vertical differentiation, the former analysing the differences in integration from one state to another, the latter looking at integration from one policy area to another across the EU.[9]

Benefits

[edit]DI can be viewed as a solution to deepening integration while widening the EU. It has been argued that DI can circumvent large practical challenges in European integration. In the context of the Eurozone crisis, the Fiscal Compact, for example, was seen as a treaty that would enable states that wished to reform the Eurozone without being blocked by other states who did not wish to do so in the same manner.[10]

The main practical strength of differentiated integration is its ability to move negotiations forward in the context of a heterogeneous Europe. This is seen by many academics as the main benefit of DI.[11] There may be multiple reasons for political impasses to arise. A member state may not wish to join or engage in implementing a policy that is being negotiated by multiple European states. They may also be unable to meet expected imposed criteria at a certain time. This is a key example where Multi-Speed DI can be seen as an effective solution. If unanimous agreement must be met, policies may be dictated by the lowest common denominator or be confronted by political deadlock. Article 20 of the Treaty of the European Union states that "enhanced cooperation shall be adopted by the Council as a last resort when it has established that the objectives of such cooperation cannot be attained within a reasonable period by the Union as a whole".[12]

There have been cases where DI has been viewed as effective in resolving deadlock. Under John Major, the British government did not wish to be part of the common currency nor the proposed social policy in 1992 during the Maastricht Treaty negotiations. The eventual flexibility offered by other member states and EU institutions regarding these key issues for the UK brought two advantages. First, it made it possible for the other states to proceed in negotiation, and second, it relieved political pressure from the British government.[13] This is an example of À La Carte DI where policy specific opt-outs are carried out by an EU member state.[3]

There may be cases where offering opt-outs within the EU's framework is not an accepted path to resolve a political impasse. In these cases, DI can take place outside the EU's framework. The 1985 Schengen agreement is the product of DI through separate treaty making.[14] This example of a variable geometry DI[3] satisfies the wish of both groups. The first group of states could open their borders to each other, deepening the process of integration much further while the states who did not want to participate in this aspect of integration had total freedom to control their borders. Thus, the process of integration can proceed with little obstruction and most parties could fulfil their perceived national interest.[15]

When aggregating the opinions of DI, most academics believe that its benefits outweigh the risks.[1]

Weaknesses

[edit]Concentric circles in variable-geometry DI and overlapping circles present in the À La Carte model entail reinforcing division and potentially alienating states from each other. This issue has been explicitly pointed out by states who felt were being pushed out of negotiations through the use of the enhanced cooperation process. The introduction of EU patents is one such case. Italy and Spain, who had some reservations regarding the language in which patents were to be submitted, explicitly stated that "the envisaged enhanced cooperation does not aim to further the objectives of the Union but to exclude a Member State from the negotiations" when they appealed before the EU Court of Justice.[16]

In the context of future accession to the EU, Schengen creates two possible paths; first, if future EU member states are expected to accept the Schengen agreement, non-Schengen EU states may be more alienated from the rest of the EU, it could even cause current states within the Schengen area to leave it. Second, if future EU member states are not expected to accept the Schengen agreement, DI would bring discrimination towards these new members and may put into question the EU's authority and legitimacy.[17] In both cases, DI brings new long-term challenges.

DI introduces issues regarding solidarity between member states. States that choose to opt-out of certain policies remove themselves from shared risks. Regarding the Schengen case, in 2011, the states directly affected by migration coming from north Africa were those who did not opt-out of the Schengen agreement. At first, solidarity between states that opted-in seemed to have been the core issue, namely between France and Italy. This was mainly due to Italy granting temporary residence permits to migrants who could then move freely within the Schengen area which led France to introduce internal border checks.[18] This crisis led the Italian prime minister to question the value not only to membership of Schengen but also to the EU.[19] In this example, division of Schengen states was present regardless of DI, but additionally, non-Schengen states did not show solidarity as they distanced themselves from the crisis since the beginning. Solidarity of all EU member states could have contributed positively to resolving the crisis, but DI in this case absolved certain states from finding common solutions.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Bellamy, Richard; Kröger, Sandra (2017-07-29). "A demoicratic justification of differentiated integration in a heterogeneous EU". Journal of European Integration. 39 (5): 625–639. doi:10.1080/07036337.2017.1332058. hdl:10871/27757. ISSN 0703-6337. S2CID 73708439. Archived from the original on 2024-05-14. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ Schimmelfennig, Frank; Winzen, Thomas (March 2014). "Instrumental and Constitutional Differentiation in the European Union". JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies. 52 (2): 357. doi:10.1111/jcms.12103. ISSN 0021-9886. S2CID 153796388. Archived from the original on 2023-04-19. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ a b c d Stubb, Alexander C-G. (June 1996). "A Categorization of Differentiated Integration". JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies. 34 (2): 283–295. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.1996.tb00573.x. ISSN 0021-9886. Archived from the original on 2024-05-14. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ Schimmelfennig, Frank (2019-08-28). "Differentiated Integration and European Union Politics". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. p. 4. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1142. ISBN 978-0-19-022863-7. Archived from the original on 2023-05-29. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ Bellamy, Richard (2022). Flexible Europe : differentiated integration, fairness, and democracy. Sandra Kröger, Marta Lorimer. Bristol, UK. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-1-5292-1994-4. OCLC 1291317909. Archived from the original on 2024-05-14. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Tamim, James (2022). "Differentiated Integration in Europe: Navigating Heterogeneity" Archived 2024-05-14 at the Wayback Machine. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.10462.04162. James Tamim

- ^ Andersen, Svein S.; Sitter, Nick (2006-09-01). "Differentiated Integration: What is it and How Much Can the EU Accommodate?". Journal of European Integration. 28 (4): 313–330. doi:10.1080/07036330600853919. ISSN 0703-6337. S2CID 154588158. Archived from the original on 2024-05-14. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ Which Europe? : the politics of differentiated Integration. Kenneth H. F. Dyson, Angelos Sepos. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. 2010. ISBN 978-0-230-55377-4. OCLC 610853030. Archived from the original on 2024-05-14. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Leuffen, Dirk (2013). Differentiated integration : explaining variation in the European Union. Berthold Rittberger, Frank Schimmelfennig. Houndsmill, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-230-24643-0. OCLC 815727629. Archived from the original on 2024-05-14. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ What is Differentiated Integration? – InDivEU Stakeholder Forums – Video I, archived from the original on 2023-04-19, retrieved 2023-04-19

- ^ Kröger, Sandra; Loughran, Thomas (2021-12-26). "The Risks and Benefits of Differentiated Integration in the European Union as Perceived by Academic Experts". JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies. 60 (3): 702–720. doi:10.1111/jcms.13301. hdl:10871/127933. ISSN 0021-9886. S2CID 245532645. Archived from the original on 2024-05-14. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ "EUR-Lex – 12012M/TXT – EN – EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2021-02-09. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ Diedrichs, Udo; Faber, Anne; Tekin, Funda; Umbach, Gaby, eds. (2011-01-13). Europe Reloaded. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG. doi:10.5771/9783845228334. ISBN 978-3-8329-6195-4. Archived from the original on 2023-04-19. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ Winzen, Thomas; Schimmelfennig, Frank (December 2016). "Explaining differentiation in European Union treaties". European Union Politics. 17 (4): 7. doi:10.1177/1465116516640386. ISSN 1465-1165. S2CID 156897242. Archived from the original on 2023-04-24. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ a b Ondarza, Nicolai (2013). "Strengthening the Core or Splitting Europe?" (PDF). Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP). pp. 15–16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-04-19. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ "Case C-274/11 (Kingdom of Spain against Council of the European Union)". 2011. Archived from the original on 2022-07-25. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ Wang, Shichen (2016-12-01). "An Imperfect Integration: Has Schengen Alienated Europe?". Chinese Political Science Review. 1 (4): 715. doi:10.1007/s41111-016-0040-0. ISSN 2365-4252.

- ^ "A Race against Solidarity: The Schengen Regime and the Franco-Italian Affair". CEPS. 2011-04-29. Archived from the original on 2023-04-19. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ "Italian minister questions value of EU membership". EUobserver. 2011-04-11. Archived from the original on 2023-04-19. Retrieved 2023-04-19.