Greenback, Tennessee

Greenback, Tennessee | |

|---|---|

Welcome sign along Morganton Road | |

| Motto(s): "Small Town, Big Heart" | |

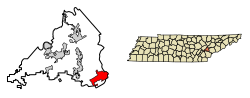

Location of Greenback in Loudon/Blount County, Tennessee. | |

| Coordinates: 35°38′55″N 84°10′21″W / 35.64861°N 84.17250°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Tennessee |

| County | Loudon |

| Founded | 1883 |

| Incorporated | 1957[1] |

| Named for | Greenback Party |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor/Aldermen Charter |

| • Mayor | Dewayne Birchfield |

| Area | |

• Total | 8.45 sq mi (21.89 km2) |

| • Land | 8.31 sq mi (21.53 km2) |

| • Water | 0.14 sq mi (0.37 km2) |

| Elevation | 892 ft (272 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 1,102 |

| • Density | 132.60/sq mi (51.20/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 37742 |

| Area code | 865 |

| FIPS code | 47-30880[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2403739[3] |

| Website | City website |

Greenback is a city in Loudon County, Tennessee, United States. Its population was at 1,102, according to the 2020 census. It is included in the Knoxville Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]Located near modern-day Greenback, Morganton Ferry (initially called Wear's Ferry) was an important crossing of the Little Tennessee. It was established in the late 18th century, and had grown into a small community known as "Portville" by 1810.[6] The community was chartered as "Morganton" after local merchant Gideon Morgan in 1813. Around this time, the Tellico agent relocated to Fort Southwest Point (now Kingston), and a road quickly developed between this fort and Maryville. Since the road crossed the Little Tennessee at the Morganton Ferry, the road became known locally as Morganton Road.[7]

In the years leading up to the Civil War, a cave in the Morganton and Greenback area is believed to have been a stop on the Underground Railroad, perhaps reflecting the area's ties to abolitionist-heavy Blount County.[8] The William H. Griffitts House, located just outside Greenback, was also a stop on the Underground Railroad.[9]

In 1859, entrepreneur Jesse Kerr established a hotel and health resort at the mineral-rich Sulphur Springs near the base of Chilhowee Mountain several miles southeast of Morganton (the resort was located near the modern junction of US-129 and TN-336). The resort was connected to Morganton Road by a stagecoach road which roughly paralleled what is now Highway 95. This resort was purchased by Indiana businessman Nathan McCoy in 1885, and a new 3-story, 60-room hotel was completed the following year. The resort was renamed "Allegheny Springs."[7]

Founding and later history

[edit]In 1876, Lorenzo Thompson established Thompson's Stand, a general store located a few miles east of modern Greenback. In 1882, Thompson applied for federal post office. He initially hoped to use the name "Thompson's Station," but the name was already in use. After several other names were rejected, Thompson settled on "Greenback," a name inspired by the local Greenback Party politician, Jonathan Tipton.[10]

In the late 1880s, the Knoxville Southern Railroad (not to be confused with the larger Southern Railway) began building a rail line connecting Knoxville with Blue Ridge, Georgia. Developers bought up the land surrounding this railroad's intersection with Morganton Road with plans to develop a town, initially known as "Allegheny" after the resort hotel to the south. Lots were sold, and a depot was constructed in 1891. Thompson moved his post office, still known as "Greenback," to the Swanay Brothers Store in the new town. The name "Greenback" gradually came to be favored over "Allegheny," and the railroad changed the name of the station to "Greenback" in 1897.[10]

By the late 1890s, Greenback had three stores, a barbershop, blacksmith shop, school, livery stables, a hotel, and two baseball teams (segregated between white and black players). The Knoxville Southern was purchased by the Marietta and North Georgia Railroad, which was in turn purchased by the Atlanta, Knoxville and Northern Railroad in 1895. The Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N), which was building a rail line between Cincinnati and Atlanta, purchased the Atlanta, Knoxville and Northern in 1902. The L&N's Greenback Depot, completed in 1914, still stands in Greenback, and has since been remodeled by Ron Edmondson as a community events center. The Greenback Drug Company, opened in 1923, still stands and has served as a community restaurant and diner for the past few decades. Locals still call it "the drugstore" and meet there for food and community.[10]

Prior to the Great Depression, thirty-four commercial buildings were constructed in Greenback. Over half of these, however, were destroyed in a series of six major fires during this period.[10] Though the community's growth slowed, Greenback was officially incorporated in 1957, with Glenn McTeer as its first mayor. A community center— built by the town's residents with no outside help or outside funding— was completed in 1978. It now houses a library, the city hall, and recreational facilities.[11]

On September 22, 1964, one of the first confrontations between the Tennessee Valley Authority and conservation groups over the proposed Tellico Dam project took place in a meeting at Greenback High School. TVA had called the meeting in hopes of gaining the support of locals, and the agency was surprised when most of the 400 or so in attendance vehemently opposed the project. TVA Chairman Aubrey Wagner, who spoke on the Authority's behalf, was continuously interrupted throughout his speech. At one point, Wagner was shouted down by legendary Monroe County judge Sue K. Hicks, who as president of the Fort Loudoun Association feared the destruction of the historic fort's site by the proposed dam's reservoir.[12]

In 2011, H&R Block featured Greenback in its national advertising campaign. The campaign, known as "Greenbacks for Greenback," included a review of many of the citizens' taxes - a program H&R Block calls "second look." The campaign saved locals more than $14,000 in taxes. The savings were revealed in a celebration with the community at Greenback School. Television, radio and print advertising featured the historic Greenback Depot, the Greenback Drugstore Diner, Greenback School and the Greenback Historical Society as well as many people who call Greenback home.

Geography

[edit]Greenback is situated around the junction of Tennessee State Route 95 and Morganton Road, with the greater community extending to U.S. Route 411 to the south and U.S. Route 321 to the north, and along Morganton Road westward to East Tellico Parkway (which follows the shores of Tellico Lake). A small commercial area is located around the intersection of Highway 411 and Highway 95.

The relatively flat land in and around Greenback is part of a valley carved by Baker Creek, a tributary of the Little Tennessee River. Chilhowee Mountain and the Great Smoky Mountains are visible to the south. The Red Knobs, part of a heavily dissected ridge typical of the Appalachian Ridge-and-Valley range, rise just north of Greenback's city limits.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 7.2 square miles (19 km2), of which 7.1 square miles (18 km2) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.26 km2) (1.80%) is water.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 285 | — | |

| 1970 | 318 | 11.6% | |

| 1980 | 546 | 71.7% | |

| 1990 | 611 | 11.9% | |

| 2000 | 954 | 56.1% | |

| 2010 | 1,064 | 11.5% | |

| 2020 | 1,102 | 3.6% | |

| Sources:[13][14][4] | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 1,026 | 93.1% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 5 | 0.45% |

| Native American | 6 | 0.54% |

| Asian | 2 | 0.18% |

| Other/Mixed | 41 | 3.72% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 22 | 2.0% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 1,102 people, 392 households, and 277 families residing in the city.

2010 census

[edit]As of the census[5] of 2010, there were 1064 people, 396 households, and 298 families residing in the city. The population density was 149.9 inhabitants per square mile (57.9/km2).

2000 census

[edit]As of the 2000 census, there were 416 housing units at an average density of 58.7 units per square mile (22.7 units/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 97.59% White, 0.94% African American, 0.21% Native American, 0.52% from other races, and 0.73% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.94% of the population.

As of the 2000 census, there were 380 households, out of which 30.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 62.1% were married couples living together, 10.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 23.9% were non-families. 22.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.51 and the average family size was 2.92.

In the city as of 2000, the population was spread out, with 3.8% under the age of 18, 8.9% from 18 to 24, 27.4% from 25 to 44, 25.8% from 45 to 64, and 14.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.3 males.

The 2000 census reported a median income for a household in the city was $31,042, and the median income for a family was $40,000. Males had a median income of $27,222 versus $23,393 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,914. About 11.1% of families and 8.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 12.6% of those under age 18 and 11.8% of those age 65 or over.

References

[edit]- ^ Tennessee Blue Book, 2005-2006, pp. 618-625.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Greenback, Tennessee

- ^ a b "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Alberta and Carson Brewer, Valley So Wild (Knoxville: East Tennessee Historical Society, 1975), pp. 92-96.

- ^ a b Inez Burns, History of Blount County, Tennessee: From War Trail to Landing Strip, 1795-1955 (Nashville: Benson Print Co., 1957), pp. 87-89, 266.

- ^ "Underground Railroad - Tennessee Stations Archived 2008-01-10 at the Wayback Machine." The Center for Historic Preservation, Middle Tennessee State University (2005). Retrieved: December 21, 2007.

- ^ "You Are Invited" (PDF). Chronicler (21). Greenback Historical Society: 1. October 1, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d Heather Bailey, "National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form for Greenback Depot Archived January 12, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, June 10, 2013, pp. 9-11. Accessed at TN.gov website: January 25, 2014.

- ^ Linda Albert, "About Greenback," The Maryville-Alcoa Daily Times, February 19, 2000.

- ^ W. Bruce Wheeler, TVA and the Tellico Dam, 1936–1979: A Bureaucratic Crisis In Post-Industrial America (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 1986), p. 64.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing: Decennial Censuses". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ^ "Incorporated Places and Minor Civil Divisions Datasets: Subcounty Resident Population Estimates: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". Population Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 11, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

External links

[edit]- Municipal Technical Advisory Service entry for Greenback Archived November 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine — information on local government, elections, and link to charter

- Greenback Historical Society