Candidatus Desulforudis audaxviator

| Desulforudis audaxviator | |

|---|---|

| |

| Desulforudis audaxviator | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Desulforudis Chivian et al. 2008

|

| Species: | Ca. D. audaxviator

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ca. Desulforudis audaxviator Chivian et al. 2008

| |

Candidatus Desulforudis audaxviator is a species of bacterium that lives in groundwater at depths from 1.5–3 kilometres (0.93–1.86 mi) below the Earth's surface. The genus is monospecific.

Etymology

[edit]The name comes from a quotation from Jules Verne's novel Journey to the Center of the Earth, where the hero, Professor Lidenbrock, finds a secret inscription in Latin: Descende, audax viator, et terrestre centrum attinges (Descend, bold traveller, and you will attain the center of the Earth).[1]

Biology

[edit]

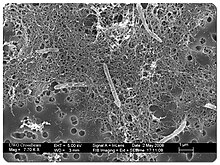

Desulforudis audaxviator is the only bacterium found in water samples obtained 2.8 kilometres (1.7 mi) underground in the Mponeng Gold Mine in South Africa.[2][3] Approximately four micrometres in length, it survives on chemical food sources derived from the radioactive decay of minerals in the surrounding rock. This makes it one of the few known organisms that does not depend on sunlight for nourishment, and the only species known to be alone in its ecosystem.[1] It has genes for extracting carbon from carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and other sources, and for fixing elemental nitrogen, though it normally gets its nitrogen from ammonia released from rocks.[4] It may also have acquired genes from a species of archaea by horizontal gene transfer.[3]

Analyses of water from the bacterium's habitat show that the water is very old and has not been diluted by surface water, indicating the bacteria have been isolated from the earth's surface for several million years.[4] As the environment at that depth is so much like the early Earth, it may indicate what types of organisms existed before there was an oxygen atmosphere. Billions of years ago, some of the planet's first bacteria may have thrived in similar conditions.

Candidatus Desulforudis audaxviator (CDA) populations have a slow evolution rate which results in high genetic similarities as they underwent minimal evolution since their physical separation from their ancestral population. A striking morphological feature of the organism is the presence of gas vesicles (provide cells the ability to flow in fluid enabling the CDA spores with this feature to spread to large distances), firstly distinguished from an early study of the closest relative of Desulforudis, Desulfotomaculum, which reported spores associated with gas vesicles and follow-up research showing that Desulfotomaculum spores could survive harsh temperature conditions and spread to the cold marine sediments.[5]

Ca. D. audaxviator is a Gram-positive sulfate-reducing microorganism. Hydrogen for this reduction comes from the radiolysis of water[5] caused by radiation from the decay chain of uranium and thorium. The radiation allows for the production of sulfur compounds that the bacteria can use as a high-energy food source. The genome contains an unusual transposon and possesses many sites of insertion. Its complete intolerance of oxygen suggests long-term isolation. It is equipped with a flagellum allowing it to swim.[4]

Ca. D. audaxviator lives in a complete absence of organic compounds, light, and oxygen, in temperatures exceeding 60 °C (140 °F) and a pH of 9.3. The physiology that enables it to live in these extreme conditions is a tribute to its unusually large genome, consisting of 2157 genes instead of the 1500 of "streamlined" bacteria found in very stable environments. If conditions become unfavorable for normal life, Ca. D. audaxviator forms a bacterial endospore, safeguarding its DNA from heat, extreme pH, and the lack of water.[6]

A 2021 study reported further findings in West Siberia, as well as in Death Valley, California.[7][8]

See also

[edit]- AngloGold Ashanti, operator of the Mponeng gold mine

- List of bacteria genera

- List of bacterial orders

- List of sequenced archaeal genomes

References

[edit]- ^ a b Eliza Strickland (2008-10-10). "Deep in a Goldmine, an Ecosystem of One". Discover magazine. Archived from the original on 2008-10-12.

- ^ Dylan Chivian; Eoin L. Brodie; Eric J. Alm; et al. (10 October 2008). "Environmental genomics reveals a single-species ecosystem deep within the Earth" (PDF). Science. 322 (5899): 275–278. Bibcode:2008Sci...322..275C. doi:10.1126/science.1155495. PMID 18845759. S2CID 8337095.

- ^ a b Catherine Brahic. "Goldmine bug DNA may be key to alien life". New Scientist. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ^ a b c "At 2.8 km down, a 1-of-a-kind microorganism lives all alone". Phys.Org. 2008-10-09. Retrieved 2013-01-21.

- ^ a b Karnachuk, Olga V.; Frank, Yulia A.; Lukina, Anastasia P.; Kadnikov, Vitaly V.; Beletsky, Alexey V.; Mardanov, Andrey V.; Ravin, Nikolai V. (August 2019). "Domestication of previously uncultivated Candidatus Desulforudis audaxviator from a deep aquifer in Siberia sheds light on its physiology and evolution". The ISME Journal. 13 (8): 1947–1959. doi:10.1038/s41396-019-0402-3. ISSN 1751-7370. PMC 6776058. PMID 30899075.

- ^ "Desulforudis audaxviator". Archived from the original on 2016-03-26. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- ^ Becraft, Eric D.; Lau Vetter, Maggie C. Y.; Bezuidt, Oliver K. I.; Brown, Julia M.; Labonté, Jessica M.; Kauneckaite-Griguole, Kotryna; Salkauskaite, Ruta; Alzbutas, Gediminas; Sackett, Joshua D.; Kruger, Brittany R.; Kadnikov, Vitaly; van Heerden, Esta; Moser, Duane; Ravin, Nikolai; Onstott, Tullis; Stepanauskas, Ramunas (October 2021). "Evolutionary stasis of a deep subsurface microbial lineage". The ISME Journal. 15 (10): 2830–2842. doi:10.1038/s41396-021-00965-3. PMC 8443664. PMID 33824425.

- "Living fossils: Microbe discovered in evolutionary stasis for millions of years". EurekAlert! (Press release). 8 April 2021.

- ^ "Microbe in Evolutionary Stasis for Millions of Years - Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences". Bigelow. 8 April 2021.