Democritus

Democritus | |

|---|---|

A philosopher, possibly Democritus. Casting of bust of the Villa of the Papyri.[1] | |

| Born | c. 460 BC |

| Died | c. 370 BC (aged approximately 90) |

| Era | Pre-Socratic philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Atomism |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas | |

Democritus (/dɪˈmɒkrɪtəs/, dim-OCK-rit-əs; Greek: Δημόκριτος, Dēmókritos, meaning "chosen of the people"; c. 460 – c. 370 BC) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe.[2] Democritus wrote extensively on a wide variety of topics.[3]

None of Democritus' original work has survived, except through second-hand references. Many of these references come from Aristotle, who viewed him as an important rival in the field of natural philosophy.[4] He was known in antiquity as the ‘laughing philosopher’ because of his emphasis on the value of cheerfulness.[5]

Life

Democritus was born in Abdera, on the coast of Thrace.[b][6] He was a polymath and prolific writer, producing nearly eighty treatises on subjects such as poetry, harmony, military tactics, and Babylonian theology. He traveled extensively, visiting Egypt and Persia, but wasn't particularly impressed by these countries. He once remarked that he would rather uncover a single scientific explanation than become the king of Persia.[3] Although many anecdotes about Democritus' life survive, their authenticity cannot be verified and modern scholars doubt their accuracy.[6] Ancient accounts of his life have claimed that he lived to a very old age, with some writers[c][d] claiming that he was over a hundred years old at the time of his death.[6]

Philosophy and science

Democritus wrote on ethics as well as physics.[7] Democritus was a student of Leucippus. Early sources such as Aristotle and Theophrastus credit Leucippus with creating atomism and sharing its ideas with Democritus, but later sources credit only Democritus, making it hard to distinguish their individual contributions.[6]

Atomic hypothesis

We have various quotes from Democritus on atoms, one of them being:

δοκεῖ δὲ αὐτῶι τάδε· ἀρχὰς εἶναι τῶν ὅλων ἀτόμους καὶ κενόν, τὰ δ'ἀλλα πάντα νενομίσθαι [δοξάζεσθαι]. (Diogenes Laërtius, Democritus, Vol. IX, 44) Now his principal doctrines were these. That atoms and the vacuum were the beginning of the universe; and that everything else existed only in opinion. (trans. Yonge 1853)

He concluded that divisibility of matter comes to an end, and the smallest possible fragments must be bodies with sizes and shapes, although the exact argument for this conclusion of his is not known. The smallest and indivisible bodies he called "atoms."[3] Atoms, Democritus believed, are too small to be detected by the senses; they are infinite in numbers and come in infinitely many varieties, and they have existed forever and that these atoms are in constant motion in the void or vacuum. The middle-sized objects of everyday life are complexes of atoms that are brought together by random collisions, differing in kind based on the variations among their constituent atoms.[3] For Democritus, the only true realities are atoms and the void. What we perceive as water, fire, plants, or humans are merely combinations of atoms in the void. The sensory qualities we experience are not real; they exist only by convention.[7] Of the mass of atoms, Democritus said, "The more any indivisible exceeds, the heavier it is." However, his exact position on atomic weight is disputed.[8]

His exact contributions are difficult to disentangle from those of his mentor Leucippus, as they are often mentioned together in texts. Their speculation on atoms, taken from Leucippus, bears a passing and partial resemblance to the 19th-century understanding of atomic structure that has led some to regard Democritus as more of a scientist than other Greek philosophers; however, their ideas rested on very different bases.[4] Democritus, along with Leucippus and Epicurus, proposed the earliest views on the shapes and connectivity of atoms. They reasoned that the solidness of the material corresponded to the shape of the atoms involved.[4] Using analogies from humans' sense experiences, he gave a picture or an image of an atom that distinguished them from each other by their shape, their size, and the arrangement of their parts. Moreover, connections were explained by material links in which single atoms were supplied with attachments: some with hooks and eyes, others with balls and sockets.[e]

The Democritean atom is an inert solid that excludes other bodies from its volume and interacts with other atoms mechanically. Quantum-mechanical atoms are similar in that their motion can be described by mechanics in addition to their electric, magnetic and quantum interactions. They are different in that they can be split into protons, neutrons, and electrons. The elementary particles are similar to Democritean atoms in that they are indivisible but their collisions are governed purely by quantum physics. Fermions observe the Pauli exclusion principle, which is similar to the Democritean principle that atoms exclude other bodies from their volume. However, bosons do not, with the prime example being the elementary particle photon.

Correlation with modern science

The theory of the atomists appears to be more nearly aligned with that of modern science than any other theory of antiquity. However, the similarity with modern concepts of science can be confusing when trying to understand where the hypothesis came from. Classical atomists could not have had an empirical basis for modern concepts of atoms and molecules.

The atomistic void hypothesis was a response to the paradoxes of Parmenides and Zeno, the founders of metaphysical logic, who put forth difficult-to-answer arguments in favor of the idea that there can be no movement. They held that any movement would require a void—which is nothing—but a nothing cannot exist. The Parmenidean position was "You say there is a void; therefore the void is not nothing; therefore there is not the void."[9][f] The position of Parmenides appeared validated by the observation that where there seems to be nothing there is air, and indeed even where there is not matter there is something, for instance light waves.

The atomists agreed that motion required a void, but simply rejected the argument of Parmenides on the grounds that motion was an observable fact. Therefore, they asserted, there must be a void.

Democritus held that originally the universe was composed of nothing but tiny atoms churning in chaos, until they collided together to form larger units—including the earth and everything on it.[2] He surmised that there are many worlds, some growing, some decaying; some with no sun or moon, some with several. He held that every world has a beginning and an end and that a world could be destroyed by collision with another world.[g]

Mathematics

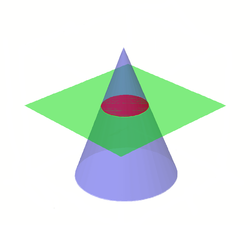

Democritus was also a pioneer of mathematics and geometry in particular. According to Archimedes,[h] Democritus was among the first to observe that a cone and pyramid with the same base area and height has one-third the volume of a cylinder or prism respectively, a result which Archimedes states was later proved by Eudoxus of Cnidus.[i][11] Plutarch[j] also reports that Democritus worked on a problem involving the cross-section of a cone that Thomas Heath suggests may be an early version of infinitesimal calculus.[11]

Anthropology

Democritus thought that the first humans lived an anarchic and animal sort of life, foraging individually and living off the most palatable herbs and the fruit which grew wild on the trees, until fear of wild animals drove them together into societies. He believed that these early people had no language, but that they gradually began to articulate their expressions, establishing symbols for every sort of object, and in this manner came to understand each other. He says that the earliest men lived laboriously, having none of the utilities of life; clothing, houses, fire, domestication, and farming were unknown to them. Democritus presents the early period of mankind as one of learning by trial and error, and says that each step slowly led to more discoveries; they took refuge in the caves in winter, stored fruits that could be preserved, and through reason and keenness of mind came to build upon each new idea.[2][k]

Ethics

Democritus was eloquent on ethical topics. Some sixty pages of his fragments, as recorded in Diels–Kranz, are devoted to moral counsel. The ethics and politics of Democritus come to us mostly in the form of maxims. In placing the quest for happiness at the center of moral philosophy, he was followed by almost every moralist of antiquity. The most common maxims associated with him are "Accept favours only if you plan to do greater favours in return", and he is also believed to impart some controversial advice such as "It is better not to have any children, for to bring them up well takes great trouble and care, and seeing them grow up badly is the cruellest of all pains".[12] He also wrote a treatise on the purpose of life and the nature of happiness. He held that "happiness was not to be found in riches but in the goods of the soul and one should not take pleasure in mortal things". Another saying that is often attributed to him is "The hopes of the educated were better than the riches of the ignorant". He also stated that "the cause of sin is ignorance of what is better" which become a central notion later in the Socratic moral thought. Another idea he propounded which was later echoed in the Socratic moral thought was the maxim that "you are better off being wronged than doing wrong".[12] His other moral notions went contrary to the then prevalent views such as his idea that "A good person not only refrains from wrongdoing but does not even want to do wrong." for the generally held notion back then was that virtue reaches it apex when it triumphs over conflicting human passions.[13]

Aesthetics

Later Greek historians consider Democritus to have established aesthetics as a subject of investigation and study,[14] as he wrote theoretically on poetry and fine art long before authors such as Aristotle. Specifically, Thrasyllus identified six works in the philosopher's oeuvre which had belonged to aesthetics as a discipline, but only fragments of the relevant works are extant; hence of all Democritus writings on these matters, only a small percentage of his thoughts and ideas can be known.

Works

Diogenes Laertius attributes several works to Democritus, but none of them have survived in a complete form.[4]

- Ethics

- Pythagoras, On the Disposition of the Wise Man, On the Things in Hades, Tritogenia, On Manliness or On Virtue, The Horn of Amaltheia, On Contentment, Ethical Commentaries

- Natural science

- The Great World-System,[l] Cosmography, On the Planets, On Nature, On the Nature of Man or On Flesh (two books), On the Mind, On the Senses, On Flavours, On Colours, On Different Shapes, On Changing Shape, Buttresses, On Images, On Logic (three books)

- Nature

- Heavenly Causes, Atmospheric Causes, Terrestrial Causes, Causes Concerned with Fire and Things in Fire, Causes Concerned with Sounds, Causes Concerned with Seeds and Plants and Fruits, Causes Concerned with Animals (three books), Miscellaneous Causes, On Magnets

- Mathematics

- On Different Angles or On contact of Circles and Spheres, On Geometry, Geometry, Numbers, On Irrational Lines and Solids (two books), Planispheres, On the Great Year or Astronomy (a calendar) Contest of the Waterclock, Description of the Heavens, Geography, Description of the Poles, Description of Rays of Light,

- Literature

- On the Rhythms and Harmony, On Poetry, On the Beauty of Verses, On Euphonious and Harsh-sounding Letters, On Homer, On Song, On Verbs, Names

- Technical works

- Prognosis, On Diet, Medical Judgment, Causes Concerning Appropriate and Inappropriate Occasions, On Farming, On Painting, Tactics, Fighting in Armor

- Commentaries

- On the Sacred Writings of Babylon, On Those in Meroe, Circumnavigation of the Ocean, On History, Chaldaean Account, Phrygian Account, On Fever and Coughing Sicknesses, Legal Causes, Problems[15]

A collections of sayings credited to Democritus have been preserved by Stobaeus, as well as a collection of sayings ascribed to Democrates which some scholars including Diels and Kranz have also ascribed to Democritus.[4]

Legacy

Diogenes Laertius claims that Plato disliked Democritus so much that he wished to have all of his books burned.[m] He was nevertheless well known to his fellow northern-born philosopher Aristotle, and was the teacher of Protagoras.[n]

Democritus is evoked by English writer Samuel Johnson in his poem, The Vanity of Human Wishes (1749), ll. 49–68, and summoned to "arise on earth, /With chearful wisdom and instructive mirth, /See motley life in modern trappings dress'd, /And feed with varied fools th'eternal jest."

-

Portrait of a philosopher, possibly Democritus. Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum.

-

Democritus among the Abderites.

-

Charles-Antoine Coypel, Cheerful Democritus, 1746.

-

2020 bust of Democritus presented to the International Atomic Energy Agency by Greece.

See also

- Atom

- John Dalton

- Democritus University of Thrace

- Kaṇāda

- Mochus

- National Centre of Scientific Research "DEMOKRITOS"

- Pseudo-Democritus

- Vaisheshika

Notes

- ^ DK B125: "ἐτεῇ δὲ ἄτομα καὶ κενόν"

- ^ Aristotle, De Coel. iii.4, Meteor. ii.7

- ^ Lucian, Macrobii 18

- ^ Hipparchus ap. Diogenes Laërtius, ix.43.

- ^ See testimonia DK 68 A 80, DK 68 A 37 and DK 68 A 43.

- ^ Aristotle, Phys. iv.6

- ^ To epitomize Democritus's cosmology, Russell[10] calls on Shelley: "Worlds on worlds are rolling ever / From creation to decay, / Like the bubbles on a river / Sparkling, bursting, borne away".

- ^ Method of Mechanical Theorems - Archimedes

- ^ Method of Mechanical Theorems - Archimedes

- ^ Plut. De Comm. 39

- ^ Diodorus I.viii.1–7.

- ^ may have been written by Leucippus

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, ix. 40: "Aristoxenus in his Historical Notes affirms that Plato wished to burn all the writings of Democritus that he could collect."

- ^ Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers Book IX, Chapter 8, Section 50.

Citations

- ^ De Petra, Giulio; Sogliano, Antonio; Patroni, Giovanni; Mariani, L.; Bassi, Domenico; Marucchi, Orazio; Conti, A. (eds.). Illustrated guide to the National Museum in Naples : sanctioned by the Ministry of education. Naples : Richter & Co. p. 68. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Barnes 1987.

- ^ a b c d Kenny, Anthony. Ancient Philosophy. Oxford Publications. p. 27. ISBN 9780198752721.

- ^ a b c d e f Berryman 2016.

- ^ Berryman, Sylvia (Spring 2023). ""Democritus", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.)". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.). Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d Taylor 1999, pp. 157–158.

- ^ a b Kenny, Anthony. Ancient Philosophy. p. 28. ISBN 9780198752721.

- ^ Russell 1972, p. 64-65.

- ^ Russell 1972, p. 69.

- ^ Russell 1972, pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b Heath 1913, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b Kenny, Anthony. Ancient Philosophy. Vol. 1. Oxford. pp. 258–259. ISBN 9780198752738.

- ^ Kenny, Anthony. Ancient Philosophy. Oxford University Press. p. 259. ISBN 9780198752721.

- ^ Tatarkiewicz 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Barnes 1987, pp. 245–246.

References

- Barnes, Jonathan (1987). Early Greek Philosophy. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044461-2. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- Berryman, Sylvia (2016). "Democritus". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Burnet, John (1892). Early Greek Philosophy. A. and C. Black. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- Couprie, Dirk L. (23 March 2011). Heaven and Earth in Ancient Greek Cosmology: From Thales to Heraclides Ponticus. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4419-8116-5. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- Heath, Thomas (1913). Aristarchus of Samos, the Ancient Copernicus: A History of Greek Astronomy to Aristarchus, Together with Aristarchus's Treatise on the Sizes and Distances of the Sun and Moon. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-06233-6.

- Popper, Karl R. (1945). The Open Society and its Enemies. Vol I.: The Spell of Plato. London: George Routledge & Sons.

- Russell, Bertrand (1972). A History of Western Philosophy. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-31400-2. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- Tatarkiewicz, Wladyslaw (2006). J. Harrell; C. Barrett; D. Petsch (eds.). History of Aesthetics. A&C Black. p. 89. ISBN 0826488552. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- Taylor, C.C.W. (1999). The Atomists, Leucippus and Democritus: Fragments : a Text and Translation with a Commentary. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-4390-0. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

Ancient testimony

- Diodorus Siculus (1st century BC). Bibliotheca historica.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.- Petronius (late 1st century AD). Satyricon. Trans. William Arrowsmith. New York: A Meridian Book, 1987.

- Sextus Empiricus (c. 200 AD). Adversus Mathematicos.

Translations

- Bakalis, Nikolaos (2005). Handbook of Greek Philosophy: From Thales to the Stoics: Analysis and Fragments, Trafford Publishing, ISBN 1-4120-4843-5.

- Freeman, Kathleen (2008). Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers: A Complete Translation of the Fragments in Diels, Forgotten Books, ISBN 978-1-60680-256-4.

Further reading

- Bailey, C. (1928). The Greek Atomists and Epicurus. Oxford.[ISBN missing]

- Barnes, Jonathan (1982). The Presocratic Philosophers, Routledge Revised Edition.[ISBN missing]

- Brumbaugh, Robert S. (1964). The Philosophers of Greece. New York: Crowell.

- Burnet, John (1914). Greek Philosophy: Thales to Plato. London: Macmillan.

- Guthrie, W. K. (1979) A History of Greek Philosophy – The Presocratic tradition from Parmenides to Democritus, Cambridge University Press.[ISBN missing]

- Kirk, G. S., J. E. Raven and M. Schofield (1983). The Presocratic Philosophers, Cambridge University Press, 2nd edition.[ISBN missing]

- Lee, Mi-Kyoung (2005). Epistemology after Protagoras: responses to relativism in Plato, Aristotle, and Democritus. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-01-99-26222-9. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- Sandywell, Barry (1996). Presocratic Reflexivity: The Construction of Philosophical Discourse c. 600–450 BC. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10170-0.

- Vlastos, Gregory (1945–1946). "Ethics and Physics in Democritus". Philosophical Review. 54–55: 53–64, 578–592.

External links

Quotations related to Democritus at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Democritus at Wikiquote Works by or about Democritus at Wikisource

Works by or about Democritus at Wikisource- "Democritus". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Democritus", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- 5th-century BC Greek philosophers

- 4th-century BC Greek people

- 4th-century BC writers

- Abderites

- Ancient Greek atomist philosophers

- Ancient Greek epistemologists

- Ancient Greek mathematicians

- Ancient Greek metaphysicians

- Presocratic philosophers

- 460s BC births

- 370s BC deaths

- 5th-century BC mathematicians

- 4th-century BC mathematicians