Delphi

Δελφοί | |

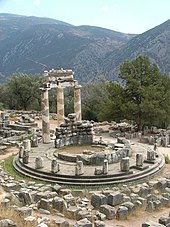

The Athena temple complex, including the Delphic Tholos. The background is the Pleistos River Valley. | |

| Location | Phocis, Greece |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°28′56″N 22°30′05″E / 38.4823°N 22.5013°E |

| Type | Ruins of an ancient sacred precinct |

| Height | Top of a scarp 500 metres (1,600 ft) maximum off the valley floor |

| History | |

| Cultures | Ancient Greece |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | French School at Athens |

| Ownership | Hellenic Republic |

| Management | Ministry of Culture and Sports |

| Public access | Accessible for a fee |

| Website | E. Partida (2012). "Delphi". Odysseus. Ministry of Culture and Sports, Hellenic Republic. |

| Official name | Archaeological Site of Delphi |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv and vi |

| Designated | 1987 (12th session) |

| Reference no. | 393 |

| Region | Europe |

Delphi (/ˈdɛlfaɪ, ˈdɛlfi/;[1] Greek: Δελφοί [ðelˈfi]),[a] in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), was an ancient sacred precinct and the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The ancient Greeks considered the centre of the world to be in Delphi, marked by the stone monument known as the Omphalos of Delphi (navel).

According to the Suda, Delphi took its name from the Delphyne, the she-serpent (drakaina) who lived there and was killed by the god Apollo (in other accounts the serpent was the male serpent (drakon) Python).[5][6]

The sacred precinct occupies a delineated region on the south-western slope of Mount Parnassus.

It is now an extensive archaeological site, and since 1938 a part of Parnassos National Park. The precinct is recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in having had a great influence in the ancient world, as evidenced by the various monuments built there by most of the important ancient Greek city-states, demonstrating their fundamental Hellenic unity.[7]

Adjacent to the sacred precinct is a small modern town of the same name.

Names

[edit]Delphi shares the same root with the Greek word for womb, δελφύς delphys.

Pytho (Πυθώ) is related to Pythia, the priestess serving as the oracle, and to Python, a serpent or dragon who lived at the site.[8] "Python" is derived from the verb πύθω (pythō),[9] "to rot".[10]

Delphi and the Delphic region

[edit]Today Delphi is a municipality of Greece as well as a modern town adjacent to the ancient precinct. The modern town was created after removing buildings from the sacred precinct so that the latter could be excavated. The two Delphis, old and new, are located on Greek National Road 48 between Amfissa in the west and Livadeia, capital of Voiotia, in the east. The road follows the northern slope of a pass between Mount Parnassus on the north and the mountains of the Desfina Peninsula on the south. The pass is of the river Pleistos, running from east to west, forming a natural boundary across the north of the Desfina Peninsula, and providing an easy route across it.

On the west side the valley joins the north–south valley between Amfissa and Itea.

On the north side of the valley junction a spur of Parnassus looming over the valley made narrower by it is the site of ancient Krisa, which once was the ruling power of the entire valley system. Both Amphissa and Krissa are mentioned in the Iliad's Catalogue of Ships.[11] It was a Mycenaean stronghold. Archaeological dates of the valley go back to the Early Helladic. Krisa itself is Middle Helladic.[12] These early dates are comparable to the earliest dates at Delphi, suggesting Delphi was appropriated and transformed by Phocians from ancient Krisa. It is believed that the ruins of Kirra, now part of the port of Itea, were the port of Krisa of the same name.[13]

Archaeology of the precinct

[edit]

The site was first briefly excavated in 1880 by Bernard Haussoullier (1852–1926) on behalf of the French School at Athens, of which he was a sometime member. The site was then occupied by the village of Kastri, about 100 houses, 200 people. Kastri ("fort") had been there since the destruction of the place by Theodosius I in 390. He probably left a fort to make sure it was not repopulated, however, the fort became the new village. They were mining the stone for re-use in their own buildings. British and French travelers visiting the site suspected it was ancient Delphi. Before a systematic excavation of the site could be undertaken, the village had to be relocated, but the residents resisted.

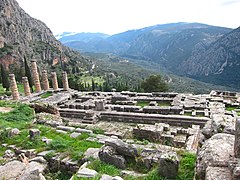

The opportunity to relocate the village occurred when it was substantially damaged by an earthquake, with villagers offered a completely new village in exchange for the old site. In 1893, the French Archaeological School removed vast quantities of soil from numerous landslides to reveal both the major buildings and structures of the sanctuary of Apollo and of the temple to Athena, the Athena Pronoia along with thousands of objects, inscriptions, and sculptures.[14]

During the Great Excavation architectural members from a fifth-century Christian basilica, were discovered that date to when Delphi was a bishopric. Other important Late Roman buildings are the Eastern Baths, the house with the peristyle, the Roman Agora, and the large cistern. At the outskirts of the city late Roman cemeteries were located.

To the southeast of the precinct of Apollo lay the so-called Southeastern Mansion, a building with a 65-meter-long façade, spread over four levels, with four triclinia and private baths. Large storage jars kept the provisions, whereas other pottery vessels and luxury items were discovered in the rooms. Among the finds stands out a tiny leopard made of mother of pearl, possibly of Sassanian origin, on display in the ground floor gallery of the Delphi Archaeological Museum. The mansion dates to the beginning of the fifth century and functioned as a private house until 580, later however it was transformed into a potter workshop.[15] It is only then, in the beginning of the sixth century, that the city seems to decline: its size is reduced and its trade contacts seem to be drastically diminished. Local pottery production is produced in large quantities:[16] it is coarser and made of reddish clay, aiming at satisfying the needs of the inhabitants.

The Sacred Way remained the main street of the settlement, transformed, however, into a street with commercial and industrial use. Around the agora were built workshops as well as the only intra muros early Christian basilica. The domestic area spread mainly in the western part of the settlement. The houses were rather spacious and two large cisterns provided running water to them.[17]

Delphi Archaeological Museum

[edit]The museum houses artifacts associated with ancient Delphi, including the earliest known notation of a melody, the Charioteer of Delphi, Kleobis and Biton, golden treasures discovered beneath the Sacred Way, the Sphinx of Naxos, and fragments of reliefs from the Siphnian Treasury. Immediately adjacent to the exit is the inscription that mentions the Roman proconsul Gallio.

Architecture of the precinct

[edit]

Most of the ruins that survive today date from the most intense period of activity at the site in the sixth century BC.[19]

Temple of Apollo

[edit]Ancient tradition refers to a succession of mythical temples on the site: first one built of olive branches from Tempe, then one built of beeswax and wings by bees, and thirdly one built by Hephaestus and Athena. The first archaeologically attested structure was built in the seventh century BC and is attributed in legend to the architects Trophonios and Agamedes.[20] It burnt down in 548/7 BC and the Alcmaeonids built a new structure which itself burnt down in the fourth century BC.

The ruins of the Temple of Apollo that are visible today date from the fourth century BC, and are of a peripteral Doric building. It was erected by Spintharus, Xenodoros, and Agathon.[21]

Treasuries

[edit]

From the entrance of the upper site, continuing up the slope on the Sacred Way almost to the Temple of Apollo, are a large number of votive statues, and numerous so-called treasuries. These were built by many of the Greek city-states to commemorate victories and to thank the oracle for her advice, which was thought to have contributed to those victories. These buildings held the offerings made to Apollo; these were frequently a "tithe" or tenth of the spoils of a battle. The most impressive is the now-restored Athenian Treasury, built to commemorate their victory at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC.

The Siphnian Treasury was dedicated by the city of Siphnos, whose citizens gave a tithe of the yield from their silver mines until the mines came to an abrupt end when the sea flooded the workings.

One of the largest of the treasuries was that of Argos. Having built it in the late classical period, the Argives took great pride in establishing their place at Delphi amongst the other city-states. Completed in 380 BC, their treasury seems to draw inspiration mostly from the Temple of Hera located in the Argolis. However, recent analysis of the Archaic elements of the treasury suggest that its founding preceded this.

Other identifiable treasuries are those of the Sicyonians, the Boeotians, Massaliots, and the Thebans.

-

Boeotians

-

Cnidians

-

Sicyonians

-

Siphnians

Altar of the Chians

[edit]Located in front of the Temple of Apollo, the main altar of the sanctuary was paid for and built by the people of Chios. It is dated to the fifth century BC by the inscription on its cornice. Made entirely of black marble, except for the base and cornice, the altar would have made a striking impression. It was restored in 1920.[14]

-

Ancient Greek inscription at the altar, naming Chios, "ΧΙΟΙΣ"

Stoa of the Athenians

[edit]

The stoa, or open-sided, covered porch, is placed in an approximately east–west alignment along the base of the polygonal wall retaining the terrace on which the Temple of Apollo sits. There is no archaeological suggestion of a connection to the temple. The stoa opened to the Sacred Way. The nearby presence of the Treasury of the Athenians suggests that this quarter of Delphi was used for Athenian business or politics, as stoas are generally found in market-places.

Although the architecture at Delphi is generally Doric, a plain style, in keeping with the Phocian traditions that were Doric, the Athenians did not prefer the Doric. The stoa was built in their own preferred style, the Ionic order, the capitals of the columns being a sure indicator. In the Ionic order they are floral and ornate, although not so much as the Corinthian, which is in deficit there. The remaining porch structure contains seven fluted columns, unusually carved from single pieces of stone (most columns were constructed from a series of discs joined). The inscription on the stylobate indicates that it was built by the Athenians after their naval victory over the Persians in 478 BC, to house their war trophies. At that time the Athenians and the Spartans were on the same side.

The Sibyl rock is a pulpit-like outcrop of rock between the Athenian Treasury and the Stoa of the Athenians upon the Sacred Way that leads up to the temple of Apollo in the archaeological area of Delphi. The rock is claimed to be the location from which a prehistoric Sibyl pre-dating the Pythia of Apollo sat to deliver her prophecies. Other suggestions are that the Pythia might have stood there, or an acolyte whose function was to deliver the final prophecy. The rock seems ideal for public speaking.

Theatre

[edit]

The ancient theatre at Delphi was built farther up the hill from the Temple of Apollo giving spectators a view of the entire sanctuary and the valley below.[22] It was originally built in the fourth century BC, but was remodeled on several occasions, particularly in 160/159 B.C. at the expenses of king Eumenes II of Pergamon and, in 67 A.D., on the occasion of emperor Nero's visit.[23]

The koilon (cavea) leans against the natural slope of the mountain whereas its eastern part overrides a little torrent that led the water of the fountain Cassotis right underneath the temple of Apollo. The orchestra was initially a full circle with a diameter measuring seven meters. The rectangular scene building ended up in two arched openings, of which the foundations are preserved today. Access to the theatre was possible through the parodoi, i.e. the side corridors. On the support walls of the parodoi are engraved large numbers of manumission inscriptions recording fictitious sales of the slaves to the deity. The koilon was divided horizontally in two zones via a corridor called diazoma. The lower zone had 27 rows of seats and the upper one only eight. Six radially arranged stairs divided the lower part of the koilon in seven tiers. The theatre could accommodate approximately 4,500 spectators.[24]

On the occasion of Nero's visit to Greece in 67 A.D. various alterations took place. The orchestra was paved and delimited by a parapet made of stone. The proscenium was replaced by a low pedestal, the pulpitum; its façade was decorated in relief with scenes from myths about Hercules. Further repairs and transformations took place in the second century A.D. Pausanias mentions that these were carried out under the auspices of Herod Atticus. In antiquity, the theatre was used for the vocal and musical contests that formed part of the programme of the Pythian Games in the late Hellenistic and Roman period.[25] The theatre was abandoned when the sanctuary declined in Late Antiquity. After its excavation and initial restoration it hosted theatrical performances during the Delphic Festivals organized by A. Sikelianos and his wife, Eva Palmer, in 1927 and in 1930. It has recently been restored again as the serious landslides posed a grave threat for its stability for decades.[26][27]

Tholos

[edit]

The tholos at the sanctuary of Athena Pronaea (Ἀθηνᾶ Προναία, "Athena of forethought") is a circular building that was constructed between 380 and 360 BC. It consisted of 20 Doric columns arranged with an exterior diameter of 14.76 meters, with 10 Corinthian columns in the interior.

The Tholos is located approximately a half a mile (800 m) from the main ruins at Delphi (at 38°28′49″N 22°30′28″E / 38.48016°N 22.50789°E). Three of the Doric columns have been restored, making it the most popular site at Delphi for tourists to take photographs.

The architect of the "vaulted temple at Delphi" is named by Vitruvius, in De architectura Book VII, as Theodorus Phoceus (not Theodorus of Samos, whom Vitruvius names separately).[28]

Gymnasium

[edit]

The gymnasium, which is half a mile away from the main sanctuary, was a series of buildings used by the youth of Delphi. The building consisted of two levels: a stoa on the upper level providing open space, and a palaestra, pool, and baths on lower floor. These pools and baths were said to have magical powers, and imparted the ability to communicate directly to Apollo.[14]

Stadium

[edit]

The stadium is located farther up the hill, beyond the via sacra and the theatre. It was built in the fifth century BC, but was altered in later centuries. The last major remodelling took place in the second century AD under the patronage of Herodes Atticus when the stone seating was built and an (arched) entrance created. It could seat 6500 spectators and the track was 177 metres long and 25.5 metres wide.[29]

Hippodrome

[edit]It was at the Pythian Games that prominent political leaders, such as Cleisthenes, tyrant of Sikyon, and Hieron, tyrant of Syracuse, competed with their chariots. The hippodrome where these events took place was referred to by Pindar,[30] and this monument was sought by archaeologists for over two centuries.

Traces of it have recently been found at Gonia in the plain of Krisa in the place where the original stadium had been sited.[31]

Polygonal wall

[edit]

A retaining wall was built to support the terrace housing the construction of the second temple of Apollo in 548 BC. Its name is taken from the polygonal masonry of which it is constructed. At a later date, from 200 BC onwards, the stones were inscribed with the manumission (liberation) contracts of slaves who were consecrated to Apollo. Approximately a thousand manumissions are recorded on the wall.[32]

Castalian spring

[edit]The sacred spring of Delphi lies in the ravine of the Phaedriades. The preserved remains of two monumental fountains that received the water from the spring date to the Archaic period and the Roman, with the latter cut into the rock.

Roman Agora

[edit]

The first set of remains that the visitor sees upon entering the archaeological site of Delphi is the Roman Agora, which was just outside the peribolos, or precinct walls, of the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi. The Roman Agora was built between the sanctuary and the Castalian Spring, approximately 500 meters away.[33] This large rectangular paved square used to be surrounded by Ionic porticos on its three sides.[34] The square was built in the Roman period, but the remains visible at present along the north and northwestern sides date to the Late Antique period.

An open market was probably established, where the visitors would buy ex-votos, such as statuettes and small tripods, to leave as offerings to the gods. It also served as an assembly area for processions during sacred festivals.[34][33]

During the empire, statues of the emperor and other notable benefactors were erected here as evidenced by the remaining pedestals.[34][33] In late, Antiquity workshops of artisans were also created within the agora.

Athletic statues

[edit]

Delphi is famous for its many preserved athletic statues. It is known that Olympia originally housed far more of these statues, but time brought ruin to many of them, leaving Delphi as the main site of athletic statues.[35] Kleobis and Biton, two brothers renowned for their strength, are modeled in two of the earliest known athletic statues at Delphi. The statues commemorate their feat of pulling their mother's cart several miles to the Sanctuary of Hera in the absence of oxen. The neighbors were most impressed and their mother asked Hera to grant them the greatest gift. When they entered Hera's temple, they fell into a slumber and never woke, dying at the height of their admiration, the perfect gift.[35]

The Charioteer of Delphi is another ancient relic that has withstood the centuries. It is one of the best known statues from antiquity. The charioteer has lost many features, including his chariot and his left arm, but he stands as a tribute to athletic art of antiquity.[35]

Myths regarding the origin of the precinct

[edit]

In the Iliad, Achilles would not accept Agamemnon's peace offering even if it included all the wealth in the "stone floor" of "rocky Pytho" (I 404). In the Odyssey (θ 79) Agamemnon crosses a "stone floor" to receive a prophecy from Apollo in Pytho, the first known of proto-history.[36] Hesiod also refers to Pytho "in the hollows of Parnassus" (Theogony 498). These references imply that the earliest date of the oracle's existence is the eighth century BC, the probable date of composition of the Homeric works.

The main myths of Delphi are given in three literary "loci".[37] H. W. Parke, the Delphi scholar, argued that the myths are self-contradictory,[b] thereby aligning with the Plutarchian epistemology that these myths are not to be taken as literal historical accounts but as symbolic narratives meant to explain oracular traditions." Parke asserts that there is no Apollo, no Zeus, no Hera, and certainly never was a great, serpent-like monster, and that the myths are pure Plutarchian figures of speech, meant to be aetiologies of some oracular tradition.

Homeric Hymn 3, "To Apollo", is the oldest of the three loci, dating to the seventh century BC (estimate).[c] Apollo travels about after his birth on Delos seeking a place for an oracle. He is advised by Telephus to choose Crissa "below the glade of Parnassus", which he does, and has a temple built. Killing the serpent that guards the spring. Subsequently, some Cretans from Knossos sail up on a mission to reconnoitre Pylos. Changing into a dolphin, Apollo casts himself on deck. The Cretans do not dare to remove him but sail on. Apollo guides the ship around Greece, ending back at Crisa, where the ship grounds. Apollo enters his shrine with the Cretans to be its priests, worshipping him as Delphineus, "of the dolphin".

Zeus, a Classical deity, reportedly determined the site of Delphi when he sought to find the centre of his "Grandmother Earth" (Gaia). He sent two eagles flying from the eastern and western extremities, and the path of the eagles crossed over Delphi where the omphalos, or navel of Gaia was found.[38][39]

According to Aeschylus in the prologue of the Eumenides, the oracle had origins in prehistoric times and the worship of Gaia, a view echoed by H. W. Parke, who described the evolution of beliefs associated with the site. He established that the prehistoric foundation of the oracle is described by three early writers: the author of the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, Aeschylus in the prologue to the Eumenides, and Euripides in a chorus in the Iphigeneia in Tauris. Parke goes on to say, "This version [Euripides] evidently reproduces in a sophisticated form the primitive tradition which Aeschylus for his own purposes had been at pains to contradict: the belief that Apollo came to Delphi as an invader and appropriated for himself a previously existing oracle of Earth. The slaying of the serpent is the act of conquest which secures his possession; not as in the Homeric Hymn, a merely secondary work of improvement on the site. Another difference is also noticeable. The Homeric Hymn, as we saw, implied that the method of prophecy used there was similar to that of Dodona: both Aeschylus and Euripides, writing in the fifth century, attribute to primeval times the same methods as used at Delphi in their own day. So much is implied by their allusions to tripods and prophetic seats... [he continues on p. 6] ...Another very archaic feature at Delphi also confirms the ancient associations of the place with the Earth goddess. This was the Omphalos, an egg-shaped stone which was situated in the innermost sanctuary of the temple in historic times. Classical legend asserted that it marked the 'navel' (Omphalos) or center of the Earth and explained that this spot was determined by Zeus who had released two eagles to fly from opposite sides of the earth and that they had met exactly over this place". On p. 7 he writes further, "So Delphi was originally devoted to the worship of the Earth goddess whom the Greeks called Ge, or Gaia. Themis, who is associated with her in tradition as her daughter and partner or successor, is really another manifestation of the same deity: an identity that Aeschylus recognized in another context. The worship of these two, as one or distinguished, was displaced by the introduction of Apollo. His origin has been the subject of much learned controversy: it is sufficient for our purpose to take him as the Homeric Hymn represents him – a northern intruder – and his arrival must have occurred in the dark interval between Mycenaean and Hellenic times. His conflict with Ge for the possession of the cult site was represented under the legend of his slaying the serpent.[40]

One tale of the sanctuary's discovery states that a goatherd, who grazed his flocks on Parnassus, one day observed his goats playing with great agility upon nearing a chasm in the rock; the goatherd noticing this held his head over the chasm causing the fumes to go to his brain; throwing him into a strange trance.[41]

The Homeric Hymn to Delphic Apollo recalled that the ancient name of this site had been Krisa.[42]

Others relate that the site was named Pytho (Πυθώ) and that Pythia, the priestess serving as the oracle, was chosen from their ranks by the priestesses who officiated at the temple. Apollo was said to have slain Python, a drako (a male serpent or a dragon) who lived there and protected the navel of the Earth.[8] "Python" (derived from the verb πύθω (pythō),[9] "to rot") is claimed by some to be the original name of the site in recognition of Python that Apollo defeated.[10]

The name Delphi comes from the same root as δελφύς delphys, "womb" and may indicate archaic veneration of Gaia at the site. Several other scholars discuss the likely prehistoric beliefs associated with the site.[d][e]

Apollo is connected with the site by his epithet Δελφίνιος Delphinios, "the Delphinian". The epithet is connected with dolphins (Greek δελφίς,-ῖνος) in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo (line 400), recounting the legend of how Apollo first came to Delphi in the shape of a dolphin, carrying Cretan priests on his back. The Homeric name of the oracle is Pytho (Πυθώ).[45] Another legend held that Apollo walked to Delphi from the north and stopped at Tempe, a city in Thessaly, to pick laurel (also known as bay tree) which he considered to be a sacred plant. In commemoration of this legend, the winners at the Pythian Games received a wreath of laurel picked in the temple.

Oracle of Delphi

[edit]The prophetic process

[edit]

Perhaps Delphi is best known for its oracle, the Pythia, or sibyl, the priestess prophesying from the tripod in the sunken adyton of the Temple of Apollo. The Pythia was known as a spokesperson for Apollo. She was a woman of blameless life chosen from the peasants of the area. Alone in an enclosed inner sanctum (Ancient Greek adyton – "do not enter") she sat on a tripod seat over an opening in the earth (the "chasm"). According to legend, when Apollo slew Python its body fell into this fissure and fumes arose from its decomposing body. Intoxicated by the vapors, the sibyl would fall into a trance, allowing Apollo to possess her spirit. In this state she prophesied. The oracle could not be consulted during the winter months, for this was traditionally the time when Apollo would live among the Hyperboreans. Dionysus would inhabit the temple during his absence.[46] Of note, release of fumes is limited in colder weather.

The time to consult Pythia for an oracle during the year was determined from astronomical and geological grounds related to the constellations of Lyra and Cygnus.[47] Similar practice was followed in other Apollo oracles too.[48]

Hydrocarbon vapors emitted from the chasm. While in a trance the Pythia "raved" – probably a form of ecstatic speech – and her ravings were "translated" by the priests of the temple into elegant hexameters. It has been speculated that the ancient writers, including Plutarch who had worked as a priest at Delphi, were correct in attributing the oracular effects to the sweet-smelling pneuma (Ancient Greek for breath, wind, or vapor) escaping from the chasm in the rock. That exhalation could have been high in the known anaesthetic and sweet-smelling ethylene or other hydrocarbons such as ethane known to produce violent trances. Although, given the limestone geology, this theory remains debatable, the authors put up a detailed answer to their critics.[49][50][51][52][53]

Ancient sources describe the priestess using "laurel" to inspire her prophecies. Several alternative plant candidates have been suggested including Cannabis, Hyoscyamus, Rhododendron, and Oleander. Harissis claims that a review of contemporary toxicological literature indicates that oleander causes symptoms similar to those shown by the Pythia, and his study of ancient texts shows that oleander was often included under the term "laurel". The Pythia may have chewed oleander leaves and inhaled their smoke prior to her oracular pronouncements and sometimes dying from the toxicity. The toxic substances of oleander resulted in symptoms similar to those of epilepsy, the "sacred disease", which may have been seen as the possession of the Pythia by the spirit of Apollo.[54]

Influence, devastations and a temporary revival

[edit]The Delphic oracle exerted considerable influence throughout the Greek world, and she was consulted before all major undertakings including wars and the founding of colonies.[f] She also was respected by the Greek-influenced countries around the periphery of the Greek world, such as Lydia, Caria, and even Egypt.

The oracle was also known to the early Romans. Rome's seventh and last king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, after witnessing a snake near his palace, sent a delegation including two of his sons to consult the oracle.[56]

In 278 BC, a Thracian (Celtic) tribe raided Delphi, burned the temple, plundered the sanctuary and stole the "unquenchable fire" from the altar. During the raid, part of the temple roof collapsed.[57] The same year, the temple was severely damaged by an earthquake, thus it fell into decay and the surrounding area became impoverished. The sparse local population led to difficulties in filling the posts required. The oracle's credibility waned due to doubtful predictions.[58]

The oracle flourished again in the second century AD, during the rule of emperor Hadrian, who is believed to have visited the oracle twice and offered complete autonomy to the city.[57] By the 4th century, Delphi had acquired the status of a city.[59]

Constantine the Great looted several monuments in Eastern Mediterranean, including Delphi, to decorate his new capital, Constantinople. One of those famous items was the bronze column of Plataea (The Serpent Column; Ancient Greek: Τρικάρηνος Ὄφις, Three-headed Serpent; Turkish: Yılanlı Sütun, Serpentine Column) from the sanctuary (dated 479 BC), relocated there from Delphi in AD 324, which can still be seen today standing destroyed at a square of Istanbul (where once upon a time was the Hippodrome of Constantinople, built by Constantine; Ottoman Turkish: Atmeydanı "Horse Square") [60] with part of one of its heads kept in the Istanbul Archaeology Museums (İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri).

Despite the rise of Christianity across the Roman Empire, the oracle remained a religious center throughout the fourth century, and the Pythian Games continued to be held at least until 424 AD;[59] however, the decline continued. The attempt of Emperor Julian to revive polytheism did not survive his reign.[57] Excavations have revealed a large three-aisled basilica in the city, as well as traces of a church building in the sanctuary's gymnasium.[59] The site was abandoned in the sixth or seventh centuries, although a single bishop of Delphi is attested in an episcopal list of the late eighth and early ninth centuries.[59]

In modern times, the structured method of communication and forecasting known as the Delphi technique takes its name from the oracle of Delphi,[61] although some founders and early developers of the technique considered that the adoption of the name "Delphi" was unfortunate and undesirable.[62]

Religious significance of the oracle

[edit]

Delphi became the site of a major temple to Phoebus Apollo, as well as the Pythian Games and the prehistoric oracle. Even in Roman times, hundreds of votive statues remained, described by Pliny the Younger and seen by Pausanias. Carved into the temple were three phrases: γνῶθι σεαυτόν (gnōthi seautón = "know thyself") and μηδὲν ἄγαν (mēdén ágan = "nothing in excess"), and Ἑγγύα πάρα δ'ἄτη (engýa pára d'atē = "make a pledge and mischief is nigh"),[63] In antiquity, the origin of these phrases was attributed to one or more of the Seven Sages of Greece by authors such as Plato[64] and Pausanias.[65] Additionally, according to Plutarch's essay on the meaning of the "E at Delphi"—the only literary source for the inscription—there was also inscribed at the temple a large letter E.[66] Among other things epsilon signifies the number 5. However, ancient as well as modern scholars have doubted the legitimacy of such inscriptions.[67] According to one pair of scholars, "The actual authorship of the three maxims set up on the Delphian temple may be left uncertain. Most likely they were popular proverbs, which tended later to be attributed to particular sages."[68]

According to the Homeric hymn to the Pythian Apollo, Apollo shot his first arrow as an infant that effectively slew the serpent Pytho, the son of Gaia, who guarded the spot. To atone the murder of Gaia's son, Apollo was forced to fly and spend eight years in menial service before he could return forgiven. A festival, the Septeria, was held every year, at which the whole story was represented: the slaying of the serpent, and the flight, atonement, and return of the god.[69]

The Pythian Games took place every four years to commemorate Apollo's victory.[69] Another regular Delphi festival was the "Theophania" (Θεοφάνεια), an annual festival in spring celebrating the return of Apollo from his winter quarters in Hyperborea. The culmination of the festival was a display of an image of the deities, usually hidden in the sanctuary, to worshippers.[70]

The theoxenia was held each summer, centred on a feast for "gods and ambassadors from other states". Myths indicate that Apollo killed the chthonic serpent Python guarding the Castalian Spring and named his priestess Pythia after her. Python, who had been sent by Hera, had attempted to prevent Leto, while she was pregnant with Apollo and Artemis, from giving birth.[71]

The spring at the site flowed toward the temple but disappeared beneath, creating a cleft which emitted chemical vapors that purportedly caused the oracle at Delphi to reveal her prophecies. Apollo killed Python, but had to be punished for it, since he was a child of Gaia. The shrine dedicated to Apollo was originally dedicated to Gaia and shared with Poseidon.[69] The name Pythia remained as the title of the Delphic oracle.

Erwin Rohde wrote that the Python was an earth spirit, who was conquered by Apollo, and buried under the omphalos, and that it is a case of one deity setting up a temple on the grave of another.[72] Another view holds that Apollo was a fairly recent addition to the Greek pantheon coming originally from Lydia.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Occupation of the site at Delphi can be traced back to the Neolithic period with extensive occupation and use beginning in the Mycenaean period (1600–1100 BC). In Mycenaean times Krissa was a major Greek land and sea power, perhaps one of the first in Greece, if the Early Helladic date of Kirra is to be believed.[73] The ancient sources indicate that the previous name of the Gulf of Corinth was the "Krisaean Gulf".[74] Like Krisa, Corinth was a Dorian state, and Gulf of Corinth was a Dorian lake, so to speak, especially since the migration of Dorians into the Peloponnesus starting about 1000 BC. Krisa's power was broken finally by the recovered Aeolic and Attic-Ionic speaking states of southern Greece over the issue of access to Delphi. Control of it was assumed by the Amphictyonic League, an organization of states with an interest in Delphi, in the early Classical period. Krisa was destroyed for its arrogance. The gulf was given Corinth's name. Corinth by then was similar to the Ionic states: ornate and innovative, not resembling the spartan style of the Doric.

Ancient Delphi

[edit]Earlier myths[75][39] include traditions that Pythia, or the Delphic oracle, already was the site of an important oracle in the pre-classical Greek world (as early as 1400 BC) and, rededicated from about 800 BC, when it served as the major site during classical times for the worship of the god Apollo.

Delphi was since ancient times a place of worship for Gaia, the mother goddess connected with fertility. The town started to gain pan-Hellenic relevance as both a shrine and an oracle in the seventh century BC. Initially under the control of Phocaean settlers based in nearby Kirra (currently Itea), Delphi was reclaimed by the Athenians during the First Sacred War (597–585 BC). The conflict resulted in the consolidation of the Amphictyonic League, which had both a military and a religious function revolving around the protection of the Temple of Apollo. This shrine was destroyed by fire in 548 BC and then fell under the control of the Alcmaeonids who were banned from Athens. In 449–448 BC, the Second Sacred War (fought in the wider context of the First Peloponnesian War between the Peloponnesian League led by Sparta and the Delian-Attic League led by Athens) resulted in the Phocians gaining control of Delphi and the management of the Pythian Games.

In 356 BC, the Phocians under Philomelos captured and sacked Delphi, leading to the Third Sacred War (356–346 BC), which ended with the defeat of the former and the rise of Macedon under the reign of Philip II. This led to the Fourth Sacred War (339 BC), which culminated in the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC) and the establishment of Macedonian rule over Greece.

In Delphi, Macedonian rule was superseded by the Aetolians in 279 BC, when a Gallic invasion was repelled, and by the Romans in 191 BC. The site was sacked by Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 86 BC, during the Mithridatic Wars, and by Nero in 66 AD. Although subsequent Roman emperors of the Flavian dynasty contributed toward to the restoration of the site, it gradually lost importance.[citation needed]

The anti-pagan legislation of the late Roman Imperial era deprived ancient sanctuaries of their assets.[citation needed] The emperor Julian attempted to reverse this religious climate, yet his "pagan revival" was particularly short-lived. When the doctor Oreibasius visited the oracle of Delphi, in order to question the fate of paganism, he received a pessimistic answer:[citation needed]

Tell the king that the flute has fallen to the ground. Phoebus does not have a home any more, neither an oracular laurel, nor a speaking fountain, because the talking water has dried out

It was shut down during the persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire by Theodosius I in 381 AD.[76]

Amphictyonic Council

[edit]The Amphictyonic Council was a council of representatives from six Greek tribes who controlled Delphi and also the quadrennial Pythian Games. They met biannually and came from Thessaly and central Greece. Over time, the town of Delphi gained more control of itself and the council lost much of its influence.

The sacred precinct in the Iron Age

[edit]

Excavation at Delphi, which was a post-Mycenaean settlement of the late ninth century, has uncovered artifacts increasing steadily in volume beginning with the last quarter of the eighth century BC. Pottery and bronze as well as tripod dedications continue in a steady stream, in contrast to Olympia. Neither the range of objects nor the presence of prestigious dedications proves that Delphi was a focus of attention for a wide range of worshippers, but the large quantity of valuable goods, found in no other mainland sanctuary, encourages that view.

Apollo's sacred precinct in Delphi was a Panhellenic Sanctuary, where every four years, starting in 586 BC[77] athletes from all over the Greek world competed in the Pythian Games, one of the four Panhellenic Games, precursors of the Modern Olympics. The victors at Delphi were presented with a laurel crown (stephanos) that was ceremonially cut from a tree by a boy who re-enacted the slaying of the Python.[77] (These competitions are also called stephantic games, after the crown.) Delphi was set apart from the other games sites because it hosted the mousikos agon, musical competitions.[10]

These Pythian Games rank second among the four stephantic games chronologically and in importance.[77] These games, however, were different from the games at Olympia in that they were not of such vast importance to the city of Delphi as the games at Olympia were to the area surrounding Olympia. Delphi would have been a renowned city regardless of whether it hosted these games; it had other attractions that led to it being labeled the "omphalos" (navel) of the earth, in other words, the centre of the world.[77][78]

In the inner hestia (hearth) of the Temple of Apollo, an eternal flame burned. After the battle of Plataea, the Greek cities extinguished their fires and brought new fire from the hearth of Greece, at Delphi; in the foundation stories of several Greek colonies, the founding colonists were first dedicated at Delphi.[79]

Abandonment and rediscovery

[edit]The Ottomans finalized their domination over Phocis and Delphi in about 1410 AD. Delphi itself remained almost uninhabited for centuries. It seems that one of the first buildings of the early modern era was the monastery of the Dormition of Mary or of Panagia (the Mother of God) built above the ancient gymnasium at Delphi. It must have been toward the end of the fifteenth or in the sixteenth century that a settlement started forming there, which eventually ended up forming the village of Kastri.

Ottoman Delphi gradually began to be investigated. The first Westerner to describe the remains in Delphi was Cyriacus of Ancona, a fifteenth-century merchant turned diplomat and antiquarian, considered the founding father of modern classical archeology.[80] He visited Delphi in March 1436 and remained there for six days. He recorded all the visible archaeological remains based on Pausanias for identification. He described the stadium and the theatre at that date as well as some freestanding pieces of sculpture. He also recorded several inscriptions, most of which are now lost. His identifications, however, were not always correct: for example he described a round building he saw as the temple of Apollo while this was simply the base of the Argives' ex-voto. A severe earthquake in 1500 caused much damage.

In 1766, an English expedition funded by the Society of Dilettanti included the Oxford epigraphist Richard Chandler, the architect Nicholas Revett, and the painter William Pars. Their studies were published in 1769 under the title Ionian Antiquities,[81] followed by a collection of inscriptions,[82] and two travel books, one about Asia Minor (1775),[83] and one about Greece (1776).[84] Apart from the antiquities, they also related some vivid descriptions of daily life in Kastri, such as the crude behaviour of the Muslim Albanians who guarded the mountain passes.[citation needed]

In 1805 Edward Dodwell visited Delphi, accompanied by the painter Simone Pomardi.[85] Lord Byron visited in 1809, accompanied by his friend John Cam Hobhouse:

Yet there I've wandered by the vaulted rill

Yes! Sighed o'er Delphi's long deserted shrine,

where, save that feeble fountain, all is still.

He carved his name on the same column in the gymnasium as Lord Aberdeen, later Prime Minister, who had visited a few years before. Proper excavation did not start until the late nineteenth century (see "Excavations" section) after the village had moved.

Delphi in later art

[edit]

From the sixteenth century onward, woodcuts of Delphi began to appear in printed maps and books. The earliest depictions of Delphi were totally imaginary; for example, those created by Nikolaus Gerbel, who published in 1545 a text based on the map of Greece by N. Sofianos. The ancient sanctuary was depicted as a fortified city.[86]

The first travelers with archaeological interests, apart from the precursor Cyriacus of Ancona, were the British George Wheler and the French Jacob Spon, who visited Greece in a joint expedition in 1675–1676. They published their impressions separately. In Wheler's "Journey into Greece", published in 1682, a sketch of the region of Delphi appeared, where the settlement of Kastri and some ruins were depicted. The illustrations in Spon's publication "Voyage d'Italie, de Dalmatie, de Grèce et du Levant, 1678" are considered original and groundbreaking.

Travelers continued to visit Delphi throughout the nineteenth century and published their books which contained diaries, sketches, and views of the site, as well as pictures of coins. The illustrations often reflected the spirit of romanticism, as evident by the works of Otto Magnus von Stackelberg, where, apart from the landscapes (La Grèce. Vues pittoresques et topographiques, Paris 1834) are depicted also human types (Costumes et usages des peuples de la Grèce moderne dessinés sur les lieux, Paris 1828). The philhellene painter W. Williams has comprised the landscape of Delphi in his themes (1829). Influential personalities such as F.Ch.-H.-L. Pouqueville, W.M. Leake, Chr. Wordsworth and Lord Byron are amongst the most important visitors of Delphi.

After the foundation of the modern Greek state, the press became also interested in these travelers. Thus "Ephemeris" writes (17 March 1889): In the Revues des Deux Mondes Paul Lefaivre published his memoirs from an excursion to Delphi. The French author relates in a charming style his adventures on the road, praising particularly the ability of an old woman to put back in place the dislocated arm of one of his foreign traveling companions, who had fallen off the horse. "In Arachova the Greek type is preserved intact. The men are rather athletes than farmers, built for running and wrestling, particularly elegant and slender under their mountain gear." Only briefly does he refer to the antiquities of Delphi, but he refers to a pelasgian wall 80 meters long, "on which innumerable inscriptions are carved, decrees, conventions, manumissions".[citation needed]

Gradually the first travelling guides appeared. The revolutionary "pocket" books invented by Karl Baedeker, accompanied by maps useful for visiting archaeological sites such as Delphi (1894) and the informed plans, the guides became practical and popular. The photographic lens revolutionized the way of depicting the landscape and the antiquities, particularly from 1893 onward, when the systematic excavations of the French Archaeological School started. However, artists such as Vera Willoughby, continued to be inspired by the landscape.[citation needed]

Delphic themes inspired several graphic artists. Besides the landscape, Pythia and Sibylla become illustration subjects even on Tarot cards.[87] A famous example constitutes Michelangelo's Delphic Sibyl (1509),[88][89][90] the nineteenth-century German engraving, Oracle of Apollo at Delphi, as well as the recent ink on paper drawing, "The Oracle of Delphi" (2013) by M. Lind.[91] Modern artists are inspired also by the Delphic Maxims. Examples of such works are displayed in the "Sculpture park of the European Cultural Center of Delphi" and in exhibitions taking place at the Archaeological Museum of Delphi.[92]

Delphi in later literature

[edit]Delphi inspired literature as well. In 1814 W. Haygarth, friend of Lord Byron, refers to Delphi in his work "Greece, a Poem". In 1888 Charles Marie René Leconte de Lisle published his lyric drama L’Apollonide, accompanied by music by Franz Servais. More recent French authors used Delphi as a source of inspiration such as Yves Bonnefoy (Delphes du second jour) or Jean Sullivan (nickname of Joseph Lemarchand) in L'Obsession de Delphes (1967), but also Rob MacGregor's Indiana Jones and the Peril at Delphi (1991).

The presence of Delphi in Greek literature is very intense. Poets such as Kostis Palamas (The Delphic Hymn, 1894), Kostas Karyotakis (Delphic festival, 1927), Nikephoros Vrettakos (return from Delphi, 1957), Yannis Ritsos (Delphi, 1961–62) and Kiki Dimoula (Gas omphalos and Appropriate terrain 1988), to mention only the most renowned ones. Angelos Sikelianos wrote The Dedication (of the Delphic speech) (1927), the Delphic Hymn (1927) and the tragedy Sibylla (1940), whereas in the context of the Delphic idea and the Delphic festivals he published an essay entitled "The Delphic union" (1930). The nobelist George Seferis wrote an essay under the title "Delphi", in the book "Dokimes".[93]

Gallery

[edit]-

The theatre at Delphi

-

Ruins of the theatre at Delphi

-

Stacked stones

-

The Phaedriades

See also

[edit]- Aristoclea, Delphic priestess of the 6th century BC, said to have been tutor to Pythagoras

- Ex voto of the Attalids (Delphi)

- Franz Weber (activist) - made an honorary citizen of Delphi in 1997

- Greek art

- List of traditional Greek place names

- Portico of the Aetolians

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ In English, the name Delphi is pronounced either as /ˈdɛlfaɪ/ or, in a more Greek-like manner, as /ˈdɛlfiː/. The bottom line on the etymology is that Delphoi is related to delphus, "womb", which is consistent with the omphalos stone there being considered the "navel" of the universe and the site being the uterus of Earth. The delphis, or "dolphin" connection, is an accidental result of the dolpins being named from their uterus-like appearance. The full etymology is to be found in Frisk.[2] The inscriptional variants, Dalphoi, Dolphoi, Derphoi,[3] might appear to be dialects, especially Dalphoi, usually taken as Phocian, as the Phocians spoke Doric. Frisk labels them as secondary developments, including the apparent Doric original a in Dalphoi. It could well be Phocian, but was not originally Doric. The true dialect form, Aeolic Belphoi, with Delphoi, must be reflexes of a Bronze Age *Gwelphoi, which does not have an original "a".[4] Frisk's Proto-Indoeuropean is *gwelbh-u-, with a -u- extension. Without the extension there is no relation between Delphoi and delphus. However, Frisk, a major Indo-Europeanist, cites some parallels of -woi- to -oi- in other words. The evidence from mythology adds strength to his hypothesis. Without the w, Delphoi is not related to Delphus, but only seems so. The etymology of dolphin is fairly standard.

- ^ "All three versions, instead of being simple and traditional, are already selective and tendentious. They disagree with each other..."

- ^ The poem has two parts, "To Delian Apollo" and "To Pythian Apollo". The Pytho myth is only in the latter.

- ^ Such was its prestige that most Hellenes after 500 BCE placed its foundation in the earliest days of the world: before Apollo took possession, they said, Ge (Earth) (Gaia) and her daughter Themis had spoken oracles at Pytho. Such has been the strength of the tradition that many historians and others have accepted as historical fact the ancient statement that Ge and Themis spoke oracles before it became Apollo's establishment, yet nothing but the myth supports this statement. In the earliest account known of the Delphic oracle's beginnings, the story found in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo (281–374), there was no oracle before Apollo came and killed the great she-dragon, Pytho's only inhabitant. This was apparently the Delphic myth of the sixth century.[43]

- ^ The earth is the abode of the dead, therefore the earth-deity has power over the ghostly world: the shapes of dreams, which often foreshadowed the future, were supposed to ascend from the world below, therefore the earth-deity might acquire an oracular function, especially through the process of incubation, in which the consultant slept in a holy shrine with his ear upon the ground. That such conceptions attached to Gaia is shown by the records of her cults at Delphi, Athens, and Aegae. A recently discovered inscription speaks of a temple of Ge at Delphi... As regards Gaia, we also can accept it. It is confirmed by certain features in the latter Delphic divination, and also by the story of the Python.[44]

- ^ Because the founding of the city was for the Greeks, as it had been for earlier cultures, primarily a religious act, Delphi naturally assumed charge of the new foundations; and especially in the early period of colonization, the Pythian Apollo gave specific advice that dispatched new colonies in every direction, under the aegis of Apollo. Few cities would undertake such an expedition without consulting the oracle. Thus at a moment when the growth of population might have led to congestion within the city, to random emigration, or to conflicts for arable land in the more densely populated regions, Delphi, willy-nilly, faced the problem and conducted a program of organized dispersal.[55]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Wells, John C. (2000) [1990]. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (new ed.). Harlow, England: Longman. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-582-36467-7.

- ^ Frisk, Hjalmar (1960). "δελφίς, Δελφοί, δελφύς". Griechisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch. Vol. Band I. Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

- ^ Also given in Henry George Liddell; Robert Scott; Henry Stuart Jones (1940). "Δελφοί". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Alice Mouton; Ian Rutherford; Ilya Yakubovich (2013). Luwian Identities: Culture, Language and Religion Between Anatolia and the Aegean. Leiden: Brill. p. 66.

- ^ "Suda, pi,3137".

- ^ "Suda, delta,210".

- ^ "Archaeological Site of Delphi". World Heritage Convention. United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ a b Konstaninou, Ioanna "Delphi: the Oracle and its Role in the Political and Social Life of the Ancient Greeks" (Hannibal Publishing House, Athens)

- ^ a b LSJ s.v. πύθω.

- ^ a b c Miller 2004, p. 95.

- ^ Kase 1970, pp. 1–2

- ^ Kase 1970, pp. 4–5

- ^ Kase 1970, p. 5

- ^ a b c Delphi Archived 2005-04-01 at the Wayback Machine, Hellenic Ministry of Culture.

- ^ Petrides, P., 1997, «Delphes dans l’Antiquité tardive : première approche topographique et céramologique», BCH 121, 681-695

- ^ Petrides, P., 2003, «Αteliers de potiers protobyzantins à Delphes », in Χ. ΜΠΑΚΙΡΤΖΗΣ (ed.), 7ο Διεθνές Συνέδριο Μεσαιωνικής Κεραμικής της Μεσογείου, Θεσσαλονίκη 11-16 Οκτωβρίου 1999, Πρακτικά, Αθήνα, 443-446

- ^ Petrides, P., 2005, «Un exemple d’architecture civile en Grèce: les maisons protobyzantines de Delphes (IVe–VIIe s.)», Mélanges Jean-Pierre Sodini, Travaux et Mémoires 15, Paris, pp. 193-204

- ^ Maurizio, Lazzari; Silvestro, Lazzari (July 2012). "Geological and Geomorphological Hazard in Historical and Archaeological Sites of the Mediterranean Area: Knowledge, Forecasting, and Mitigation". Disaster Advances. 5 (3): 69.

- ^ Sakoulas, Thomas. "Delphi Archaeological Site". Ancient-Greece.org. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ Bowra, C.M. (2000). Pindar. Oxford University Press. pp. 373–75.

- ^ Sakoulas, Thomas. "Temple of Apollo at Delphi". Ancient-Greece.org. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ Bommelaer, J.-F. (1991). Guide de Delphes: Le site. Paris: Laroche, D. pp. 207–212.

- ^ Delphi Theater at Ancient-Greece.org.

- ^ Bommelaer, J.-F. «Das Theater», in Maas, M. (ed), Delphi. Orakel am Nabel der Welt, Karlsruhe 1996, pp. 95-105

- ^ Mulliez, D., "Οι πυθικοί αγώνες. Οι μαρτυρίες των επιγραφών", in Κολώνια, Ρ. (ed.), Αρχαία Θέατρα της Στερεάς Ελλάδας, Διάζωμα, Αθήνα 2013, 147-154

- ^ "ΑΡΧΑΙΟ ΘΕΑΤΡΟ ΔΕΛΦΩΝ : Παρελθόν - Παρόν - Μέλλον : ΧΟΡΗΓΙΚΟΣ ΦΑΚΕΛΟΣ". Diazoma.gr. Retrieved 5 March 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Χλέπα, Ε.-Α., Παπαντωνόπουλος, Κ., «Τεκμηρίωση και αποκατάσταση του αρχαίου θεάτρου Δελφών», in Κολώνια, Ρ. (ed.), Αρχαία Θέατρα της Στερεάς Ελλάδας, Διάζωμα, Αθήνα 2013, 173-198

- ^ "Marcus Vitruvius Pollio: de Architectura, Book VII". University of Chicago. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Delphi Stadium at Ancient-Greece.org.

- ^ Pindar: Pythian 3

- ^ "Hippodrome of ancient Delphi located". archaeologynewsnetwork.blogspot.co.uk. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Manumission Wall Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine at Ashes2Art; Manumission of female slaves at Delphi at attalus.org.

- ^ a b c Aimatidou-Argyriou, Eleni (2003). Delphi. Athens: Spyros Meletzis Archive. pp. 52–53. ISBN 960-91259-4-8.

- ^ a b c Petrakos, Basil (1977). Delphi. Athens: Clio Editions. p. 15.

- ^ a b c Miller 2004, p. 98.

- ^ Lloyd-Jones 1976, p. 60

- ^ Parke 1939, p. 6

- ^ Graves, Robert (1993), "The Greek Myths: Complete Edition" (Penguin, Harmondsworth)

- ^ a b Harissis 2019

- ^ Herbert William Parke, The Delphic Oracle, v. 1, p. 3.

- ^ William Godwin (1876). Lives of the Necromancers. London, F. J. Mason. p. 11.

- ^ Hymn to Pythian Apollo, l. 254–74: Telphousa recommends to Apollo to build his oracle temple at the site of "Krisa below the glades of Parnassus".

- ^ Fontenrose, Joseph (1978). The Delphic Oracle: Its Responses and Operations, with a Catalogue of Responses, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Farnell, Lewis Richard, The Cults of the Greek States, v. III, pp. 8–10, onwards.

- ^ Odyssey, VIII, 80

- ^ See e.g. Fearn 2007, p. 182

- ^ Liritzis, I.; Castro, B. (2013). "Delphi and Cosmovision: Apollo's absence at the land of the hyperboreans and the time for consulting the oracle". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 16 (2): 184. Bibcode:2013JAHH...16..184L. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1440-2807.2013.02.04. S2CID 220659867.

- ^ Castro, Belen; Liritzis, Ioannis; Nyquist, Anne (2015). "Oracular Functioning And Architecture of Five Ancient Apollo Temples Through Archaeoastronomy: Novel Approach And Interpretation". Interpretation Nexus Network Journal, Architecture & Mathematics. 18 (2): 373. doi:10.1007/s00004-015-0276-2.

- ^ Spiller, Henry A.; Hale, John R.; de Boer, Jelle Z. (2002). "The Delphic Oracle: A Multidisciplinary Defense of the Gaseous Vent Theory" (PDF). Clinical Toxicology. 40 (2): 189–196. doi:10.1081/clt-120004410. PMID 12126193. S2CID 38994427. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-11-28.

- ^ John Roach (14 August 2001). "Delphic Oracle's Lips May Have Been Loosened by Gas Vapors". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 24 September 2001. Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- ^ Spiller, Henry; de Boer, Jella; Hale, John R.; Chanton, Jeffery (2008). "Gaseous emissions at the site of the Delphic Oracle: Assessing the ancient evidence". Clinical Toxicology. 46 (5): 487–488. doi:10.1080/15563650701477803. PMID 18568810. S2CID 12441885.

- ^ Piccardi, Luigi (2000). "Active faulting at Delphi, Greece: Seismotectonic remarks and a hypothesis for the geologic environment of a myth". Geology. 28 (7): 651–654. Bibcode:2000Geo....28..651P. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2000)28<651:AFADGS>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Piccardi, Luigi; Monti, Cassandra; Vaselli, Orlando; Tassi, Franco; Gaki-Papanastassiou, Kalliopi; Papanastassiou, Dimitris (January 2008). "Scent of a myth: tectonics, geochemistry and geomythology at Delphi (Greece)". Journal of the Geological Society. 165 (1): 5–18. Bibcode:2008JGSoc.165....5P. doi:10.1144/0016-76492007-055. S2CID 131225069.

- ^ Harissis, Haralampos V. (2014). "A Bittersweet Story: The True Nature of the Laurel of the Oracle of Delphi". Perspect. Biol. Med. 57 (3): 351–360. doi:10.1353/pbm.2014.0032. PMID 25959349. S2CID 9297573. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ Lewis Mumford, The City in History. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961; p. 140.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1.56

- ^ a b c Lampsas Giannis (1984) Dictionary of the Ancient World (Lexiko tou Archaiou Kosmou), Vol. I, Athens, Domi Publications, pp. 761-762

- ^ Wood, Michael (2003). The road to Delphi : the life and afterlife of oracles (1st ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-52610-9. OCLC 52090516.

- ^ a b c d Gregory, Timothy E. (1991). "Delphi". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. London; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 602. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- ^ Scott, Michael (2014). Delphi: A History of the Center of the Ancient World (1st ed.). Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press. pp. 240–241. ISBN 978-0-691-15081-9.

- ^ Sheridan, T., "Computers/Future of Delphi: Technology for Group Dialogue" in Linstone, H. A. and Turoff, M. (2002), The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications, p. 529, archived on 20 September 2008, accessed on 13 July 2024

- ^ Ziglio E (1996). "The Delphi Method and its Contribution to Decision Making". In Adler M, Ziglio E (eds.). Gazing Into the Oracle: The Delphi Method and Its Application to Social Policy and Public Health. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-85302-104-6.

- ^ Plato, Charmides 164d–165a.

- ^ Plato, Protagoras 343a–b at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, Phocis and Ozolian Locri, 10.24.1 at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Hodge, A. Trevor. "The Mystery of Apollo's E at Delphi", American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 85, No. 1. (Jan., 1981), pp. 83–84.

- ^ H. Parke and D. Wormell, The Delphic Oracle, (Basil Blackwell, 1956), vol. 1, pp. 387–389.

- ^ Parke & Wormell, p. 389.

- ^ a b c Cf. Seyffert, Dictionary of Classic Antiquities, article on "Delphic Oracle" Archived 2007-02-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ James Hall, A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Art, pp 70–71, 1983, John Murray, London, ISBN 0719539714

- ^ Michael Grant; John Hazel (2 August 2004). Who's Who in Classical Mythology. Routledge. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-134-50943-0.

- ^ Rodhe, E (1925), Psyche: The Cult of Souls and the Belief in Immortality among the Greeks, trans. from the 8th edn. by W. B. Hillis (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1925; reprinted by Routledge, 2000). p. 97

- ^ Kase 1970, pp. 16–17

- ^ Kase 1970, pp. 28–29

- ^ Pausanias 10.12.1

- ^ Grecia. Guida d'Europa (in Italian). Milano: Touring Club Italiano. 1977. p. 126.

- ^ a b c d Miller 2004, p. 96.

- ^ Miller 2004, p. 97.

- ^ Burkert 1985, pp. 61, 84.

- ^ Edward W. Bodnar, Later travels, with Clive Foss

- ^ Chandler, R, Revett, N., Pars, W., Ionian Antiquities, London 1769

- ^ Chandler, R, Revett, N., Pars, W., Inscriptiones antiquae, pleraeque nondum editae, in Asia Minore et Graecia, praesertim Athensis, collectae, Oxford, 1774

- ^ Chandler, R, Revett, N., Pars, W., Travels in Asia Minor, Oxford, 1775.

- ^ Chandler, R, Revett, N., Pars, W., Travels in Greece, Oxford, 1776.

- ^ A classical and topographical tour through Greece, London 1819

- ^ Tolias, George (2006). "Nikolaos Sophianos's Totius Graeciae Descriptio: The Resources, Diffusion and Function of a Sixteenth-Century Antiquarian Map of Greece". Imago Mundi. 58 (2): 150–182. doi:10.1080/03085690600687214. hdl:10442/13763. S2CID 54885024.

The views are imaginary, and some are reproductions or variants of older woodcuts of German towns here used for Greek towns.

- ^ "Tarot of Delphi". Aeclectic.net. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Michelangelo (1509). Delphic Sibyl. Wikimedia Commons (painting).

- ^ John Collier (1891). The Priestess of Delphi (painting).

- ^ John William Waterhouse (1882). Consulting the Oracle. JWWaterhouse.com (painting).

- ^ Malin Lind (22 January 2013). The Oracle of Delphi. theshapeshifter.wordpress.com (ink on paper). Delphi – Art, creation of life. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "Delphic Spirit by Aristides Patsoglou - theDelphiGuide.com". thedelphiguide.com. 2021-11-13. Retrieved 2024-08-16.

- ^ Yiannias, Vicky (October 6, 2003). "Lecture on Seferis at the Hellenic Culture Foundation". Greek News. Archived from the original on 2021-04-18. Retrieved 2021-04-18.

Citation references

[edit]- Aimatidou-Argyriou, E. Delphi, Athens 2003

- Bommelaer, J.-F., Laroche, D., Guide de Delphes. Le site, Paris 1991

- Broad, William J. The Oracle: Ancient Delphi and the Science Behind its Lost Secrets, New York : Penguin, 2006. ISBN 1-59-420081-5.

- Burkert, Walter (1985). Greek Religion.

- Connelly, Joan Breton, Portrait of a Priestess: Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece, Princeton University Press, 2007. ISBN 0691127468

- Call of Duty: Black Ops 4 (2018) "Ancient Evil"

- Dempsey, T., Reverend, The Delphic oracle, its early history, influence and fall, Oxford: B.H. Blackwell, 1918.

- Castro Belen, Liritzis Ioannis and Nyquist Anne (2015) Oracular Functioning And Architecture of Five Ancient Apollo Temples Through Archaeastronomy: Novel Approach And Interpretation Nexus Network Journal, Architecture & Mathematics, 18(2), 373-395 (DOI:10.1007/s00004-015-0276-2)

- Farnell, Lewis Richard, The Cults of the Greek States, in five volumes, Clarendon Press, 1896–1909. (Cf. especially, volume III and volume IV on the Pythoness and Delphi).

- Fearn, David (2007). Bacchylides: Politics, Performance, Poetic Tradition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199215508.

- Fontenrose, Joseph Eddy, The Delphic oracle, its responses and operations, with a catalogue of responses, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978. ISBN 0520033604

- Fontenrose, Joseph Eddy, Python; a study of Delphic myth and its origins, New York, Biblio & Tannen, 1974. ISBN 081960285X

- Goodrich, Norma Lorre, Priestesses, New York: F. Watts, 1989. ISBN 0531151131

- Guthrie, William Keith Chambers, The Greeks and their Gods, 1955.

- Hall, Manly Palmer, The Secret Teachings of All Ages, 1928. Ch. 14 cf. Greek Oracles, www, PRS

- Harissis H. 2015. "A Bittersweet Story: The True Nature of the Laurel of the Oracle of Delphi" Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. Volume 57, Number 3, Summer 2014, pp. 295-298.

- Harissis, H. (2019). "Pindar's Paean 8 and the birth of the myth of the first temples of Delphi". Acta Classica: Proceedings of the Classical Association of South Africa. 62 (1): 78–123.

- Herodotus, The Histories

- Homeric Hymn to Pythian Apollo

- Kase, Edward W. (1970). A Study of the Role of Krisa in the Mycenaean Era (Master's Thesis). Loyola University. Docket 2467.

- Kolonia, R., The Archaeological Museum of Delphi, Athens 2006

- Liritzis, I; Castro, Β (2013). "Delphi and Cosmovision: Apollo's absence at the land of the hyperboreans and the time for consulting the oracle". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 16 (2): 184–206. Bibcode:2013JAHH...16..184L. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1440-2807.2013.02.04. S2CID 220659867.

- Lloyd-Jones, Hugh (1976). "The Delphic Oracle". Greece & Rome. 23 (1): 60–73. doi:10.1017/S0017383500018283. S2CID 162187662.

- Manas, John Helen, Divination, ancient and modern, New York, Pythagorean Society, 1947.

- Miller, Stephen G. (2004). Ancient Greek Athletics. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300100839.

- Parke, Herbert William (1939). A history of the Delphic oracle. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Petrakos, B. Delph, Athens 1977

- Plutarch "Lives"

- Rohde, Erwin, Psyche, 1925.

- Seyffert, Oskar, "Dictionary of Classical Antiquities" Archived 2009-02-25 at the Wayback Machine, London: W. Glaisher, 1895.

- Spiller, Henry A., John R. Hale, and Jelle Z. de Boer. "The Delphic Oracle: A Multidisciplinary Defense of the Gaseous Vent Theory." Clinical Toxicology 40.2 (2000) 189–196.

- West, Martin Litchfield, The Orphic Poems, 1983. ISBN 0-19-814854-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Adornato, G (2008). "Delphic Enigmas? The Γέλας ἀνάσσων, Polyzalos, and the Charioteer Statue". American Journal of Archaeology. 112 (1): 29–55. doi:10.3764/aja.112.1.29. S2CID 157508659.

- Davies, J. K. (1998). Finance, Administrations, and Realpolitik: The Case of Fourth-Century Delphi. In Modus Operandi: Essays in Honour of Geoffrey Rickman. Edited by M. Austin, J. Harries, and C. Smith, 1–14. London: Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, Suppl. 71.

- Davies, John. (2007). "The Origins of the Festivals, especially Delphi and the Pythia." In Pindar’s Poetry, Patrons, and Festivals: From Archaic Greece to the Roman Empire. Edited by Simon Hornblower and Catherine Morgan, 47–69. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Giangiulio, Maurizio (2015). "Collective Identities, imagined past, and Delphi". In Foxhall, Lin; Gehrke, Hans-Joachim; Luraghi, Nino (eds.). Intentional History : Spinning Time in Ancient Greece. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 121–136. ISBN 978-3-515-11288-8.

- Kindt, Julia. (2016). Revisiting Delphi: Religion and Storytelling in Ancient Greece. Cambridge Classical Studies. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Maurizio, Lisa (1997). "Delphic Oracles as Oral Performances: Authenticity and Historical Evidence". Classical Antiquity. 16 (2): 308–334. doi:10.2307/25011067. JSTOR 25011067.

- McInerney, Jeremy (2011). "Delphi and Phokis: A Network Theory Approach". Pallas. 87 (87): 95–106. doi:10.4000/pallas.1948.

- McInerney, Jeremy (1997). "Parnassus, Delphi, and the Thyiades". Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies. 38 (3): 263–284.

- Morgan, Catherine. (1990). Athletes and Oracles. The Transformation of Olympia and Delphi in the Eighth Century BC. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Partida, Elena C. (2002). The Treasuries at Delphi: An Architectural Study. Jonsered, Denmark: Paul Åströms.

- Scott, Michael, Delphi: A History of the Center of the Ancient World (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014). ISBN 978-0-691-15081-9

- Scott, Michael. (2010). Delphi and Olympia: The Spatial Politics of Panhellenism in the Archaic and Classical Periods. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Temple, Robert K.G., "Fables, Riddles, and Mysteries of Delphi", Proceedings of 4th Philosophical Meeting on Contemporary Problems, No 4, 1999 (Athens, Greece) In Greek and English.

- Weir, Robert G. (2004). Roman Delphi and its Pythian games. BAR Series 1306. Oxford: Hadrian.

5th-century evidence

[edit]- Petrides, P., 2010, La céramique protobyzantine de Delphes. Une production et son contexte, École française d’Athènes, Fouilles de Delphes V, Monuments figurés 4, Paris – Athènes.

- Petrides, P., Déroche, V., Badie, A., 2014,Delphes de l’Antiquité tardive. Secteur au Sud-est du Péribole, École française d’Athènes, Fouilles de Delphes II, Topographie et Architecture 15, Paris-Athènes.

- Petrides, P., 1997, «Delphes dans l’Antiquité tardive : première approche topographique et céramologique», BCH 121, pp. 681–695.

- Petrides, P., 2003, «Αteliers de potiers protobyzantins à Delphes », in Χ. ΜΠΑΚΙΡΤΖΗΣ (ed.), 7ο Διεθνές Συνέδριο Μεσαιωνικής Κεραμικής της Μεσογείου, Θεσσαλονίκη 11-16 Οκτωβρίου 1999, Πρακτικά, Αθήνα, pp. 443–446.

- Petrides, P., 2005, «Un exemple d’architecture civile en Grèce : les maisons protobyzantines de Delphes (IVe–VIIe s.)», Mélanges Jean-Pierre Sodini, Travaux et Mémoires 15, Paris, pp. 193–204.

- Petrides, P., Demou, J., 2011, « La redécouverte de Delphes protobyzantine », Pallas 87, pp. 267–281.

External links

[edit]- E. Partida (2012). "Delphi Archaeological Museum". Odysseus. Ministry of Culture and Sports, Hellenic Republic.

- Online books, and library resources in your library and in other libraries about Delphi

- VirtualDelphi will help you picture the monuments of Delphi by reconstructing their sight and placing them in their historical time frame.

- Delphi

- Cities in ancient Greece

- Ancient Greek sanctuaries in Greece

- Classical oracles

- Temples of Apollo

- World Heritage Sites in Greece

- Former theatres in Greece

- Archaeological sites in Central Greece

- Tourist attractions in Central Greece

- Ancient Greek archaeological sites in Greece

- Phocis

- Ancient Delphi

- Populated places in Phocis