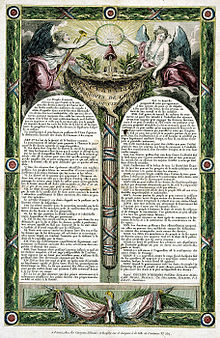

Declaration of the Rights of the Man and of the Citizen of 1793

The Declaration of the Rights of the Man and of the Citizen of 1793 (French: Déclaration des droits de l'Homme et du citoyen de 1793) is a French political document that preceded that country's first republican constitution. The Declaration and Constitution were ratified by popular vote in July 1793, and officially adopted on 10 August; however, they never went into effect, and the constitution was officially suspended on 10 October. It is unclear whether this suspension was thought to affect the Declaration as well. The Declaration was written by the commission that included Louis Antoine Léon de Saint-Just and Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles during the period of the French Revolution. The main distinction between the Declaration of 1793 and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789 is its egalitarian tendency: equality is the prevailing right in this declaration. The 1793 version included new rights, and revisions to prior ones: to work, to public assistance, to education, and to resist oppression.[1]

The text was mainly written by Hérault de Séchelles, whose style and writing can be found on most of the documents of the commission that also wrote the French Constitution of 1793 ("Constitution of the Year I") that was never implemented.[2] The first project of the Constitution of the French Fourth Republic also referred to the 1793 version of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. The 1793 document was written by Jacobins after they had expelled the Girondists. It was a compromise designed as a propaganda weapon and did not fully reflect the radicalism of the Jacobin leaders. It was never put in force.[3]

Equality as the first natural right of man

[edit]Equality is the most important aspect of the Declaration of 1793. In its second article, equality is the first right mentioned (followed by liberty, security, and property). In Article 3 states "All men are equal by nature and before the law". As such, for the authors of this declaration equality is not only before the law but it is also a natural right, that is to say, a fact of nature.

There was already at that time a school of thought that stated that liberty and equality can quickly become contradictory; liberty does not solve social inequalities since there exist some natural inequalities (of talent, intelligence, etc.). That school of thought considered that the government had only to protect liberty and to only proclaim natural equality, and eventually liberty would prevail over social equality since all people have different talents and abilities and are free to exercise them.

The question raised by this declaration is how to solve social inequalities. Article 21 states that every citizen has a right to public help, that society is indebted to each citizen, and therefore has the duty to help them. Citizens have there a right to work and society has a duty to provide relief to those who cannot work. Article 22 declares a right to education. These rights are considered the "second generation rights of Man", economic and social rights (the first ones would be natural or political). These rights entail a greater government intervention in order to reach society's goal as stated in Article 1: common welfare.

Protections of Liberty

[edit]Individual liberty is still a primary right and some aspects are more precisely defined than in Declaration of 1789. The declaration explicitly states the freedom of religion, of assembly, and of the press (Article 7), of commerce (Article 17), and of petition (Article 32). Slavery is prohibited by Article 18, which states: "Every man can contract his services and his time, but he cannot sell himself nor be sold: his person is not an alienable property."

Protections of the citizens against their own government

[edit]If in a way, this declaration has a more liberal bent in the modern American sense, since it states that there ought to be public policies for the general welfare, it also contains some very strong libertarian aspects. Article 7 states, "The necessity of enunciating these rights supposes either the presence or the fresh recollection of despotism." Article 9: "The law ought to protect public and personal liberty against the oppression of those who govern." Article 33 states that resisting tyranny is a logical consequence of the rights of man: "Resistance to oppression is the consequence of the other rights of man". Article 34 states that if one is oppressed, everyone is. Article 27 states, "Let any person who may usurp the sovereignty be instantly put to death by free men." Although the usurpation of sovereignty is not detailed, sovereignty is explained in article 25 as residing "in the people". There is no doubt that this way of thinking deeply influenced the revolutionary government during the Reign of Terror. Article 35 states, "When the government violates the rights of the people, insurrection is for the people and for each portion of the people the most sacred of rights and the most indispensable of duties." Although this declaration was never enforced (like the Constitution of 1793), history has shown that the French people have followed this advice with many successful (1830, 1848) and unsuccessful (1832, 1870) revolutions throughout the 19th century.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Gregory Fremont-Barnes, ed. (2007). Encyclopedia of the Age of Political Revolutions and New Ideologies, 1760–1815. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 159 vol 1. ISBN 9780313334450.

- ^ Jean-Antoine-Nicolas de Caritat marquis de Condorcet (2012). Condorcet: Political Writings. Cambridge UP. p. 12. ISBN 9781107021013.

- ^ Louis R. Gottschalk, The Era of the French Revolution (1929) pp. 236–38