David Riazanov

David Riazanov | |

|---|---|

Дави́д Ряза́нов | |

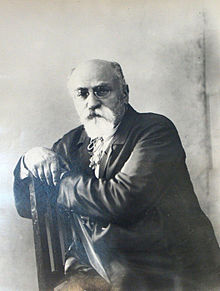

Riazanov in 1923 | |

| Born | David Borisovich Goldendakh 10 March 1870 |

| Died | 21 January 1938 (aged 67) |

| Cause of death | Execution |

David Riazanov (Russian: Дави́д Ряза́нов), born David Borisovich Goldendakh (Russian: Дави́д Бори́сович Гольдендах; 10 March 1870 – 21 January 1938), was a Russian revolutionary, historian, bibliographer and archivist. He had been an old associate of Leon Trotsky.[1][2] Riazanov founded the Marx–Engels Institute and edited the first large-scale effort to publish the collected works of these two founders of the modern socialist movement. Riazanov was a prominent victim of the Great Terror of the late 1930s.

Early years

[edit]David Borisovich Goldendakh was born 10 March 1870 to a Jewish father and a Russian mother in Odesa, Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire.[3] At the age of 15, the future David Riazanov joined the ranks of the Narodnik revolutionaries attempting to overthrow the autocracy of the Russian Tsar.[4] Riazanov attended secondary school in Odesa but was expelled in 1886, not for revolutionary activity or insubordination, but rather due to "hopeless inability."[3]

Riazanov traveled abroad in 1889 and 1891 where he met various Russian Marxists who were building their revolutionary organizations there.[4] Following his second trip, Riazanov was arrested in October 1891 at the Austrian-Russian border by the Okhrana, the tsarist secret police, who had long suspected his revolutionary activity.[5] Riazanov spent 15 months in prison awaiting trial, at which he was convicted and sentenced to an additional four years of katorga (exile and hard labor).[4] Following completion of his term, Riazanov was subject to 3 years of administrative exile under police supervision in the city of Kishinev, Bessarabia (today part of Moldova).[1]

First period of exile

[edit]In 1900, Riazanov went into exile. The next year in Berlin Riazanov and his co-thinkers established a small Marxist group called "Borba" (Struggle), which attempted to unite the émigré Russian Marxists.[1] Riazanov's group was excluded from the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party that was held in London and Brussels in the summer of 1903.[6] With the party divided between Bolshevik and Menshevik wings in the aftermath of this landmark convention, Riazanov and his co-thinkers pointedly declined to join either faction.[1]

In 1903, Riazanov became the first writer to introduce the concept of permanent revolution to the political literature of Russian Marxism when he published three studies in Geneva under the title Materials on the Program of the Workers' Party.[6] Riazanov argued, in opposition to the views of Georgi Plekhanov, that the rise of capitalism in Russia represented a fundamental departure from the pattern seen elsewhere in Europe. The large size and centralization of Russian industrial firms suggested to Riazanov a relative weakness of Russian middle-classes and a significant possibility that there would be forces of the Russian Marxist movement which would lead the revolution against Tsarist autocracy and thenceforth immediately towards socialism.[6]

Riazanov returned to Russia shortly after the start of the 1905 Russian Revolution, going to work in the trade union movement in the capital city of Saint Petersburg.[4] The uprising ended in failure by the revolutionaries, however, and Riazanov was arrested and sentenced to deportation once again in 1907.[7]

Second period of exile

[edit]Shortly after his 1907 conviction, Riazanov emigrated to the West. During this second interlude abroad, Riazanov dedicated himself to historical scholarship, studying the history of the International Workingmen's Association in the archives of the German Social-Democratic Party and in the British Museum in London.[4]

While in London, Riazanov read extensively from the files of the New-York Tribune and other newspapers, collecting material written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels for the periodical press.[8] This journalism of Marx and Engels which Riazanov so painstakingly gathered was eventually published in book form in 1917, a publication which cemented Riazanov's reputation as one of the world's leading experts in the literary output of these two leading lights of modern socialism.[8]

During Riazanov's second period of exile he became a close political associate of Leon Trotsky, contributing regularly to the latter's Vienna newspaper, Pravda.[1] Riazanov actively supported Trotsky's Interdistrict Committee (the Mezhraionka), a group which shared the internationalist views of the Bolsheviks on the question of the war but which disagreed with them on organizational matters, seeking unity with revolutionary elements in the Menshevik camp.[9]

Riazanov was also a participant in the 1915 Zimmerwald Conference of the Second International. Riazanov rejected both the social-patriotic support of World War I advanced by many Western European socialists as well as the revolutionary defeatism advanced by the Bolsheviks.[1]

During the war, Riazanov lived in Paris, where he was a frequent contributor to the Russian-language socialist newspapers Golos (The Voice) and Nashe Slovo (Our Word).[10]

After the 1917 revolution

[edit]Riazanov returned to Russia following the February Revolution in 1917. There he was active in the growing trade union movement, helping to form the Russian Railway Union.[11]

Together with the rest of the Mezhraiontsy, Riazanov joined the Bolshevik Party headed by Vladimir Lenin in August 1917.[1] Riazanov was opposed to the October Revolution, however, and was instead involved in an effort to establish a broad coalition government.[1] In the same vein, Riazanov stood as an opponent of the Bolshevik decision to dissolve the elected Constituent Assembly in January 1918.[1]

In March 1918, the decision of the Bolsheviks to sign the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk prompted Riazanov to resign from the Bolshevik Party — a temporary move which was shortly reversed with a reapplication for membership and readmission.[1]

In 1918, Riazanov helped to establish the Socialist Academy of Social Sciences, an institute later known as the Communist Academy.[1]

In 1920 Riazanov attended the 2nd World Congress of the Communist International as a member of the Russian delegation.[10]

Riazanov was an unorthodox member of the Bolshevik Party. He attended the 4th All-Russian Congress of Trade Unions in May 1921, at which he spoke in favor of the independence of the unions from the Communist Party.[12] Working with Communist trade union leader Mikhail Tomsky, Riazanov also authored a resolution calling for wages to be paid with physical commodities rather than the devalued currency of the day — an action which put the duo at odds with Lenin, Stalin, and the party's Central Committee.[12]

Radical French writer Boris Souvarine later lauded Riazanov's activity in this period as that of "a conscious marxist, a democratic communist, in other words, opposed to any dictatorship over the proletariat."[7] Riazanov's defense of trade union autonomy against the will of the party came at price, however, as Riazanov was effectively excluded from any active political responsibility after May 1921.[1] Thereafter he assumed the role of Marxist academic.

In 1921 Riazanov established the Marx-Engels Institute, which became one of the main institutions of Soviet philosophy and history.[10] Riazanov dedicated himself especially to the compilation and publication of the collected writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. In this context, as early as 1926, the publication of a multi-volume series called the Marx-Engels Archive, collecting scholarship on the biography and writings of the founders of Marxism, began under Riazanov's supervision.[13] In 1927 the first volume of the Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (MEGA1) was published by the Marx-Engels Institute, a complete edition of the works of Marx and Engels in their original languages, which was to comprise 42 volumes. Under Riazanov's editorship, five volumes of this edition were issued until 1931 (later seven more were published until the project was abandoned in the mid-1930s).[14] Moreover, starting in 1928, a first Russian edition of the collected works of Marx and Engels in 28 volumes (Sochineniya1) began being published, of which ten volumes were issued under Riazanov's direction until 1931 (vol. I–III, V–VIII, XXI–XXIII; the edition was largely completed in 1947).[15]

Riazanov also edited the works of other authors including Diderot, Feuerbach, and Hegel. He was a member of the Commission for the Study of the October Revolution and of the Russian Communist Party, commonly known as Istpart.[1]

In 1929, Riazanov was elected to the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union.[1]

Personality

[edit]Victor Serge described Riazonov as "stout, strong-featured, beard and moustache thick and white, attentive eyes, Olympian forehead, stormy temperament, ironic utterance..." and noted that "the leaders were a little afraid of his frank way of talking."[16]

He undoubtedly had a "frank way of talking." The US journalist, William Reswick, heard a rumor in Moscow - which may be apocryphal - that Riazanov once told Stalin to his face: "You recite passages from Marx like a dull schoolboy without knowing what they mean."[17] Even if it was untrue, the fact that the story was being repeated shows that he had a reputation for having a sharp tongue. Historian Isaac Deutscher recounted another episode at a party meeting in which he derided Stalin with the words "Stop it Koba, don't make a fool of yourself. Everybody knows that theory is not exactly your field".[18]

In the same vein, György Lukács mentioned how Riazanov said to him, commenting on Lukács's falling-out with the Comintern in the late 1920s: "Ah-ha, you have been Cominterned."[19]

Addressing the Eleventh Party Congress in March 1922, after he had effectively been banned from political activity, Riazonov claimed:

They say that the English Parliament can do everything except change a man into a woman. Our Central Committee is far more powerful than that. It has already changed one not very revolutionary man into an old woman, and the number of these old women is increasing daily."[20]

Persecution, death, and legacy

[edit]In December 1930, Isaak Rubin, a research assistant at the Marx-Engels Institute since 1926, was arrested by the Soviet secret police and charged with participation in a plot to establish an underground organization called the "Union Bureau of Mensheviks."[21] As a lawyer, Rubin initially managed to avoid succumbing to false charges made by the interrogator, but he was nonetheless kept in custody and transferred to Suzdal.[21]

In Suzdal, Rubin was subjected to a cramped punishment cell barely bigger than a man and to the torture of solitary confinement.[22] With his health starting to fail, Rubin was eventually compelled to give false written testimony against David Riazanov to the secret police. Rubin claimed that he had kept an envelope containing secret documents of the mythical "Menshevik Center" in his office at the Marx-Engels Institute before discreetly passing them along to David Riazanov.[23] Following a show trial conducted by prosecutor Nikolai Krylenko, Rubin was found guilty of participation in the plot and sentenced to a 5-year term of imprisonment.[23] This coerced testimony of Rubin was used in building a case against his former employer, David Riazanov.[24]

With his name under a cloud of suspicion and with a show trial of the purported "Union Bureau of Mensheviks" in the offing, Riazanov was dismissed as director of the Marx-Engels Institute in February 1931.[1]

Soon after the completion of the March trial of the Union Bureau — the so-called 1931 Menshevik Trial — with his name besmirched by false testimony,[25] Riazanov was expelled from the Communist Party and arrested by the secret police,[26] ostensibly "for helping Menshevik counter-revolutionary activity."[10]

Following his arrest, Riazanov was not sent to the labor camps of the Gulag but was instead subjected to administrative deportation to the city of Saratov.[27] In Saratov, Riazanov worked for the next six years in the Saratov University library.[28] Riazanov's Marx-Engels Institute was consolidated with the Lenin Institute later in 1931 to form the Marx–Engels–Lenin Institute, under the direction of Vladimir Adoratsky.[27]

During the Yezhovshchina of 1937, Riazanov was again arrested, this time as a purported member of a "right-opportunist Trotskyist organisation."[28] On 21 January 1938, following a perfunctory trial, the Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court condemned Riazanov to death and he was executed later that same day.[28]

Riazanov was posthumously rehabilitated in 1958.[28] He was further rehabilitated in political terms in 1989 as part of the glasnost campaign of Mikhail Gorbachev.[28]

According to historian Colum Leckey, David Riazanov's chief achievement lay in the realm of Marxology — acquiring, preparing, and publishing for the first time previously unknown writings of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels.[29] Included among these were the works The German Ideology, sections of Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right and Dialectics of Nature.[29]

Works

[edit]- Anglo-russkia otnosheniia v otsenke K. Marksa: Istoriko-kriticheskii etiud. (Ango-Russian Relations in the Estimation of K. Marx: A Historico-Critical Study.) Petrograd: Izdanie Petrogradskago Soveta rabochikh i krasnoarmeiskikh deputatov, 1918.

- G.V. Plekhanov i gruppa "Osvobozhdenie truda". (G.V. Plekhanov and the "Emancipation of Labor" Group.) Moscow: Otdel pechati Moskovskogo Soveta rabochikh i krasnoarmeiskikh deputatov, 1919.

- Международный пролетариат и война. Сборник статей 1914-1916 г. (The International Proletariat and the War: Collection of Articles, 1914–1916.)

- Institut K. Marksa i F. Engelʹsa pri V.Ts.I.K. (The Institute of K. Marx and F. Engels of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee.) Moscow: Moskovskii Rabochii, 1923.

- Zadachi profsoiuzov do i v epokhu diktatury proletariata. (The Tasks of the Unions preceding and during the Epoch of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat.) Kharkov: Proletarii, 1923.

- Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Joshua Kunitz, trans. New York: International Publishers, 1927.

- Karl Marx: Man, Thinker, and Revolutionist. A Symposium. (Editor.) London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1927.

- Vzgliady Marksa i Engel'sa na brak i semiu. (The Views of Marx and Engels on Marriage and the Family.) Moscow: Molodaia gvardiia, 1927. —Reissued in translation as Communism and Marriage.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o David Longley, "David Borisovich Riazanov" in A. Thomas Lane (ed.), Biographical Dictionary of European Labor Leaders: M-Z. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1995; pp. 804-805.

- ^ Deutscher, Isaac (5 January 2015). The Prophet: The Life of Leon Trotsky. Verso Books. p. 1206. ISBN 978-1-78168-721-5.

- ^ a b Colum Leckey, "David Riazanov and Russian Marxism," Russian History/Histoire Russe, vol. 22, no. 2 (Summer 1995), pg. 129.

- ^ a b c d e Alexander Trachtenberg, "Introduction" to D. Riazanov, Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. New York: International Publishers, 1927; pg. 5.

- ^ Leckey, "David Riazanov and Russian Marxism," pg. 130.

- ^ a b c Richard B. Day and Daniel Gaido (eds.), Witnesses to Permanent Revolution: The Documentary Record. [2009] Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2011; pp. 32-34.

- ^ a b Boris Souvarine, "D.B Riazonov," La Critique sociale, no. 2, July 1931, pp. 49-50.

- ^ a b Trachtenberg, "Introduction" to Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, pg. 6.

- ^ George Jackson and Robert Devlin (eds.), Dictionary of the Russian Revolution. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1989; pp. 347-348.

- ^ a b c d Branko Lazitch with Milorad M. Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern: New, Revised, and Expanded Edition. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1986; pg. 398.

- ^ Boris Souvarine, Stalin: A Critical Survey of Bolshevism. C.L.R. James, trans. New York: Alliance Book Corporation, 1939; pp. 191-192.

- ^ a b Roy Medvedev, Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism. George Shriver, trans. Revised Edition. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989; pg. 96.

- ^ Trachtenberg, "Introduction" to Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, pg. 7.

- ^ Musto, Marcello (October 2008). "Marx in the Years of Herr Vogt: Notes toward an Intellectual Biography (1860–1861); 1. The Editorial Vicissitudes of Marx's and Engels' Works". Science & Society. 72 (4): 389–390. doi:10.1521/siso.2008.72.4.389.

- ^ Hecker, Rolf (2001). "Die Herausgabe der ersten russischen Werkausgabe und des Marx-Engels-Archivs unter dem neuen Direktor" [The publication of the first Russian edition and the Marx-Engels Archive under the new director]. Beiträge zur Marx-Engels-Forschung. Neue Folge. Sonderband (in German). 3: 206–211.

- ^ Serge, Victor (1984). Memoirs of a Revolutionary. London: Writer & Readers Co-Operative. pp. 250–51. ISBN 0-86316-070-0.

- ^ Reswick, William (1952). I Dreamt Revolution. Chicago: Henry Regnery. p. 280. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ^ Deutscher, I. (1961). Stalin a Political Biography. p. 290.

- ^ Lukács, György (1983). Record of a Life. Verso. p. 88.

- ^ Schapiro, Leonard (1965). The Origin of the Communist Autocracy - Political Opposition in the Soviet State: First Phase, 1917-1922. New York: Frederick A. Praeger. pp. 336–37.

- ^ a b Medvedev, Let History Judge, Revised Edition, pg. 280.

- ^ Medvedev, Let History Judge, Revised Edition, pg. 281.

- ^ a b Medvedev, Let History Judge, Revised Edition, pg. 282.

- ^ Medvedev, Let History Judge, Revised Edition, pg. 283.

- ^ In 1999 the transcripts of written statements to the secret police gathered in preparation for the 1931 Menshevik Trial were published in two volumes, including the accusations made against Riazanov by I.I. Rubin, V.V. Sher, and others. See: A.L. Litvin (ed.), Men'shevistskii protsess 1931 goda: Sbornik dokumentov v 2-kh knigakh. (The Menshevik Trial of 1931: Collection of Documents in 2 Volumes.) Moscow: ROSSPEN, 1999.

- ^ Medvedev, Let History Judge, Revised Edition, pg. 292.

- ^ a b Robert C. Tucker, Stalin in Power: The Revolution from Above, 1928-1941. New York: W.W. Norton, 1990; pp. 170-171.

- ^ a b c d e Day and Gaido (eds.), Witnesses to Permanent Revolution, pg. 70.

- ^ a b Leckey, "David Riazanov and Russian Marxism," pp. 134-135.

Further reading

[edit]- Colum Leckey, "David Riazanov and Russian Marxism," Russian History/Histoire Russe, vol. 22, no. 2 (Summer 1995), pp. 127–153.

- Richard B. Day and Daniel Gaido (eds.), Witnesses to Permanent Revolution: The Documentary Record. [2009] Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2011.

- A. Deborin (ed.), Na boevom postu: Sbornik k shestidesyatiletiyu D.B. Ryazanova. (On the Battle Line: Collection for the 60th Birthday of D.B. Riazanov.) Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe Izdatel'stvo, 1930. —Pages 623-650 include a complete bibliography of Riazanov's publications.

- Hugo Cerqueira, "David Riazanov e a edição das obras de Marx e Engels". (Texto para discussão n° 352) Belo Horizonte: Cedeplar/UFMG, 2009. In Portuguese.

External links

[edit]- 1870 births

- 1938 deaths

- People from Kherson Governorate

- Politicians from Odesa

- Communist Party of the Soviet Union members

- Expelled members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

- Academic staff of Ural State University

- Full Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences

- Russian Constituent Assembly members

- Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members

- Recipients of the Lenin Prize

- Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour

- Archivists

- Great Purge victims from Ukraine

- Jewish socialists

- Marxist theorists

- Narodniks

- Odesa Jews

- Old Bolsheviks

- Soviet rehabilitations