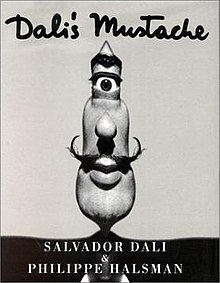

Dali's Mustache

| |

| Author | Salvador Dalí and Philippe Halsman |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Philippe Halsman |

| Language | English (2nd and 3rd edition in French) |

| Genre | Artists' books, photo-book |

| Publisher | Simon & Schuster 1984: Les Éditions Arthaud, 1995: Éditions Flammarion |

Publication date | 1954 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

| ISBN | 2080124331 |

Dali's Mustache is an absurdist humorous book by the surrealist artist Salvador Dalí (1904–1989) and his friend, the photographer Philippe Halsman (1906–1979). The first edition was published in October 1954 in New York; slightly modified French editions followed in the 1980s and 1990s.

The book is subtitled A Photographic Interview.[1] On one page a short question is addressed to Dalí, which the artist answers at the bottom of the following page. An additional, corresponding black and white photograph by Halsman – absurd, ironic or self-ironic portraits of Dalí with very different uses of his iconic mustache – complements the answer, usually with an absurd aspect.

Publishing history

[edit]Halsman lived and worked since 1940 – and until his death – in the United States. In 1941 he met Dalí in New York, who, after earlier visits to the States, stayed there with Gala from 1940 until 1948 and worked there as a writing and painting artist. Halsman and Dalí became friends and stayed friends for the rest of their lives.

The idea for the book came from Richard "Dick" Simon, one of the founders of Simon & Schuster, when Halsman showed him photographs of Dalí, which were intended for Life magazine. Already five years earlier, Simon had suggested to Halsman to make a book about the French actor Fernandel, and The Frenchman: A Photographic Interview with Fernandel[2] had sold very well.[3]

Halsman suggested the project to Dalí with the remark, that there are many books about artists, but that it had never been done before – and that would be a very special homage – that a whole book was dedicated to "a detail of the artist". Dalí liked this idea. Over the months, a project cooperation developed, to which both artists contributed ideas and put them into effect together.

The first edition of Dali's Mustache was published in October 1954 by Simon & Schuster, New York, completely in English. Halsman had translated the peculiar French of the Catalan Dalí in the preface. The backside of the book shows a "Warning! This book is preposterous".

Changes were made in the following editions, which were published in France in the 1980s and 1990s: While the original title was kept, the subtitle, the questions and answers were translated into French and the warning on the backside was replaced with Attention! Livre absurde. The Mona Lisa photograph with coins was replaced by the original with Dollar bills and the French editor added a Note de l'éditeur in which details concerning the photographic techniques are given (D'interet seulement pour les photographes).

Contents

[edit]Dedication

[edit]Both artists dedicated the book to their spouses (Dalí und Gala (Elena Ivanovna Diakonova) got married in 1934, Halsman and Yvonne Moser in 1936).

To Gala who is the guardian angel of my mustache also.

— Salvador Dalí, French: À Gala qui est aussi l'ange gardien de ma moustache.

To Yvonne for whom I shave daily.

— Philippe Halsman, French: À Yvonne pour qui je me rase tous les jours.

Preface (Salvador Dalí)

[edit]In the first part of the preface,[4] Dalí explains in first-person narrative his development from childhood to his "first American campaign". A black and white photo of Dalí holding a copy of the Time magazine from December 14, 1936[5][6] is shown with the statement, that he appeared at that time with "the smallest mustache in the world", which soon "like the power of my imagination, continued to grow".

In the second part – the mustache has become an important part of the artist – Dalí changes the narrative point of view and writes about Dalí in third-person. He mentions Delila, who also knew about the power of hair and makes a reference to "Laporte", the "inventor" of the Magia naturalis, who considered facial hair as sensitive antennas, which could pick up creative inspirations. Via Platon and Leonardo da Vinci and their "glory of facial hair", Dalí reaches the 20th century, "in which the most sensational hairy phenomenon was to occur: that of Salvador Dali's mustache".

Photographic Interview

[edit]Dali's Mustache contains 28 black and white photographs, mostly portraits of Dalí with different uses of his iconic mustache.

On the page preceding each photograph – the reader is not yet able to see it – a short question is addressed to Dalí concerning his personality or his actions, which is answered on the following page below the photograph. These answers are mostly short and occasionally cryptic; some of them seem to make sense, others are completely absurd, and in one case Dalí does not answer at all. The visual impact of Halsman's photographs adds additional meaning to Dalí's words.

Four of the photographs are allusions to Dalí's pleasure about financial success – one of them openly with dollar bills,[7] another one with American coins. Around 1940, André Breton coined the derogatory nickname "Avida Dollars", an anagram for "Salvador Dalí", which may be more or less translated as "eager for dollars".[8] Dalí never hid his financial intentions. In the book he shows self-irony in a photograph, showing him smiling and his mustache S-shaped in form of the dollar sign.[9]

Another photo shows Mona Lisa with the face of Dalí and one original $10,000 bill in each of his strong hands. In one way, this is an interpretation of the well-known ready-made L.H.O.O.Q. of the French-American painter Marcel Duchamp from the time of Dadaism, which shows the world-famous painting of the Mona Lisa with mustache and goatee. On the other hand, Dali – identified by his trademark mustache – is personified as the new icon in place of the (former) "art icon La Gioconda".[10][11]

The last photo is a good example of Halsman's and Dalí's intentions and also involves the reader.

- Question: "I have the feeling, to have discovered your secret, Salvador. Could it be that you are crazy?"[12]

- Answer: "I am certainly saner than the person who bought this book."[13]

- Above this answer, Halsman′s photograph of "Dalí, saner than the person who bought this book" is shown.

Postface (Philippe Halsman)

[edit]Besides the publishing history, Halsman talks in the postface in an anecdotic way about challenges, which arose during the work on the photographs:

Photograph No. 15 was inspired by Dalí's painting The Persistence of Memory. It shows Dalí's face on the soft melting pocket watch. From the technical point of view, this photo was the most demanding of the series and required more than hundred hours of work. Later, this photograph was taken for the photograph of a painting – which it is not.

Photograph No. 18 shows a fly and honey on Dalí's mustache.[14] In the frame of time an insurmountable problem arose: Where can you find a fly in a cold New York winter?[15]

Photograph No. 21 shows Dalí, peeking with one eye through a hole in a slice of cheese, while the tips of his mustache poke through two additional holes. The slice of Gruyère cheese was fatty, the holes were too small, assistants had to hold the tips of Dalí's mustache and in consequence the artist lost some hair during the process.

More photographs were taken than appeared finally in the book. According to his accounts, even Halsman's children were seized by "mustachomania" and made suggestions of their own.

At the end of the postface (in the French edition), Halsman recalls a conversation with a young actress, who asked him questions about Dalí, surrealism and the meaning of the mustache, pictures of which she had seen in the English edition. Halsman had explained, that Dalí's mustache is a symbol and relates the message, that everybody in their own way should believe to be different, unique and irreplaceable – whereupon the young woman exclaimed: "A mustache with a message! How can one be so absurd?" Halsman had answered her: "Do you really believe that – or do you just want to flatter me?"

Notes of the editor

[edit]The notes of the editor of the French edition refer in detail to the technical realization of selected photographs ("Comment furent faites certaines des photographies. D'interêt seulement pour les photographes").

Reception

[edit]Halsman's photographs and Dali's Mustache were reviewed and commented on in many journals and books.[16]

The catalogue of the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart states 1989: "It contains some of the best photographs of Dalí, photographs, which originated from his own instructions."[17]

Photographic journals judge it to be "a great classic"[18] and "a delightfully clever photographic album ... and collectors item".[19] A book from the first edition, which contains drawings, comments and a dedication from Dalí for Robert Schwartz, a U.S. immigration official who handled V.I.P.s, was auctioned off for 6.875 US-Dollars in 2012.[20]

The writer Michael Elsohn Ross calls it "a wild and crazy little book" and suggests to teenagers and students, to use it as an example how they can be artistically creative with their own hair (hair art).[21]

The ethologist, writer and surrealist painter Desmond Morris makes references to Dalí's mustache in his book The Naked Man: A Study of the Male Body (2008). Morris suspects Dali's Mustache to be the only book, which ever was published describing exclusively the facial hair of a single individuum.[22]

In 1991/92, the Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida, organized an exhibition of Halsman's photographs from Dali's Mustache.[23]

Background information

[edit]From "the smallest mustache of the world" to "trademark"

[edit]

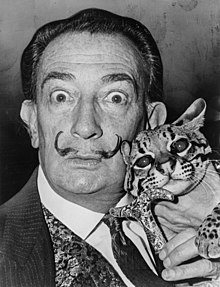

In the middle of the 1920s Salvador Dalí was clean-shaven.[24] At the end of the 1920s or beginning of the 1930s, he grew a Menjou mustache, which was popular at that time[25] – and called it himself "the smallest mustache of the world".[4] It is also documented in a 1933 photograph, one year before Dalí and Gala got married.[26] Dalí kept this kind of mustache until the end of the 1930s.

The works of several photographers – Philippe Halsman (1942),[27] Irving Penn (1947),[28] Alfredo Valente (c. 1950)[29] and again Halsman (1954)[30] – show, that Dalí started in the United States to grow longer tips of his mustache,[31] until they stood out like antennea in the 1950s[22][32] – Dali's Mustache was published 1954 – and had reached a total length of 25 centimeters.[31]

Excentric, extroverted appearances were typical for Dalí and his distinctive mustache became a "gimmick"[33] and his unofficial "trademark" with high recognition effect.[25] In the 1950s, his mustache became an iconic part of him and "the transformation of Dalí into his public appearance was nearly complete".[34]

During a fundraising campaign from Movember, MSN HIM 2010 conducted a poll to identify "the best-known mustache of all time". 14,144 votes were cast and 24% (1st place) voted for Dalí's mustache.[35]

In the literature superlatives, remarkable descriptions and unusual interpretations are found when attempts are made, to explain Dalí and his mustache:

The mustache is "a major part of his [Dalí's] uniform as an eccentric artist",[21] a "strange hallmark",[36] Dalís am leichtesten erkennbares Merkmal,[37] "Dalis most recognizable trait", "exaggerated ... feature of his post-1940 identity",[37] a pop icon[38] with "phallic overtones",[39] a "gravity-defying",[40] "heavily waxed and flexible work of art"[21]

. Gertrude Stein, who knew Dalí personally and admired him, judged "that moustache is Saracen there is no doubt about that" and thought of it to be the "most beautiful moustache of any European".[41][42]

With advancing age, the mustache got shorter again. One of the last photographs of the artist – taken by Helmut Newton in Dalís home in 1986,[43] three years after the painter had presented his last work – shows the 82 year old with a grey and drooping moustache.

Potentially inspirational antetypes

[edit]Both, Salvador Dalí und Luis Buñuel, friends since study times, admired the actor Adolphe Menjou.[44] In 1928, Buñuel had dedicated an article in La Gaceta Literaria with the title Variations on Menjou's Mustache[45] to the actor's facial hair.[46] Dalí – "Le surréalisme, c'est moi".[47] – declared Menjou's mustache as surrealistic with the statement "La moustache d'Adolphe Menjou est surréaliste".[48] During these days, the young surrealist and non-smoker drew attention in company, by offering fake mustaches from a silver cigarette case to other people with the words "Moustache? Moustache?" Moustache?",[49] but usually nobody dared to touch them.[4]

-

Adolphe Menjou (1923)

-

Salvador Dalí (1934)

-

Luis Buñuel (1968)

-

Philipp IV (1605–1665)

-

Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

-

Marcel Proust (1871–1922)

Who or what inspired Dalí to wear his moustache in the way which became typical for him, is still under debate. In this context, two other famous Spaniards are referred to: The first is the Spanish painter Velázquez,[25][50] whom Dalí admired[51] by interpreting his paintings in his own artistic way. The second is Felipe IV de España (Philipp IV of Spain),[52] also called Philipp the Great (Felipe el Grande) or Planet King (El Rey Planeta), who was said to have had a keen sense of humour and a "great sense of fun",[53] who composed poems and painted himself, who supported arts and poetry during his reign and who had called Velázquez as court painter to the Spanish court. Salvador Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech had the same given name "Felipe" and still today in Dalí's house – between two candle holders designed by the artist – a framed photograph of a Velázquez painting of Philipp IV can be found.[54]

Dalí himself brought Marcel Proust into the debate, whom he had already read as a juvenile and whose writing style – long sentences, metaphors – Dalí practiced, too.[55][56] But Dalí invoked his name only in a comparison: "[The mustache] is the most serious part of my personality. It's a very simple Hungarian mustache. Mister Marcel Proust used the same kind of pomade for this mustache."[32]

Dalí′s mustache in self-promotion, advertising and literature

[edit]The high recognition effect of Dalís mustache has led to a variety of mostly commercial applications.

In the 1960s the singer Françoise Hardy was popular and had a very positive image. Other celebrities were interested, to be close to her or to be seen with her.[57] In October 1968, Jean Marie Périer, a well-known photographer of the musical scene of that time, shot a whole series of photographs of Hardy together with Dalí on his property in Spain. One of the photos shows the painter transforming Hardy into a copy of himself by using her own hair shaped into Dalí's mustache.[58]

In 1974, the German editor Rogner & Bernhard published the collected literary works of Dalí. For the cover, a black and white photograph was chosen, showing only the artist's profile from chin to nose, with Dalí's characteristic mustache right in the middle.[59]

The Salvador Dalí Museum in Saint Petersburg uses a graphic icon of Dalí's mustache on its website.[60] When the museum moved into new buildings, in 2010, a public campaign was started using a gigantic three-dimensional mustache on a billboard. Since 2011, this varnished mustache from styrofoam with a length of 40 feet (~ 12 m) and a height of 14 feet (~ 4.2 m) can be found next to the museum and has become a tourist attraction.[61]

With the purpose of an advertising campaign for the Italian Civita Art School with the motto "Artists born here", an advertising agency in Rome designed a "Baby Dalí", who alone by his mustache is associated with the artist.[62]

In the novel La Moustache de Dali from Kenan Görgün the painter reflects – beyond his death – on his art and his mustache.[63]

See also

[edit]Comments and references

[edit]- ^ In the later French editions Une Interview Photographique.

- ^ Philippe Halsman: The Frenchman: A Photographic Interview with Fernandel (engl.), 1. ed., Simon & Schuster, New York (1949).

- ^ Halsman mentions in the postface of Dali's Mustache, that he still drives a Cabrio, which he affectionally calls "Fernandel" and which he owes to the financial success of this book.

- ^ a b c "Preface of Dali′s Mustache by Salvador Dalí". Archived from the original on 2015-11-27. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- ^ "Surrealist Salvador Dali" Archived 2016-02-08 at the Wayback Machine. Time. December 14 1936.

- ^ Dalí and Gala had arrived one week earlier, on December 7th 1936, for reason of an exhibition in the Julien Levy Gallery – December 10th until January 9th 1937 – in New York City.

- ^ Due to American legislation in 1954 it was forbidden to depict Dollar bills photographically in the original edition. In the French editions a substitute n durch Originale mit Dollarnoten ersetzt.[clarification needed]

- ^ Artcyclopedia: Salvador Dalí. Retrieved September 4, 2006.

- ^ Shanes, Eric (2011). Dalí. Parkstone International. p. 70. ISBN 978-1780426594.

- ^ Gianluca Spinato: Mona Lisa as a Modern Icon, www.academia.edu; retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ^ La Joconde et cette histoire de moustaches, Worldpress, 18 November 2011; retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ^ In French: "J'ai le pressentiment d'avoir découvert votre secret, Salvador. Ne serriez-vous pas fou?"

- ^ In French: "Je suis certainement plus sensé que la personne qui a acheté ce livre."

- ^ Dalí insisted to have a photo of a fly (mouche) on his mustache (French: moustache).

- ^ The description of the problem, attempts and the final solution requires one whole page of the postface. Efforts of Yvonne Halsman are mentioned, who broke into tears, when a creative attempt of hers failed. Finally, work was postponed until next spring and this photo was taken in the absence of Dalí, who had returned by then back to Europe.

- ^ "Dalí i Halsman, Bibliografia llibres i catàlegs | Textos en descàrrega | Fundació Gala – Salvador Dalí". www.salvador-dali.org.

- ^ Karin von Maur, Marc Lacroix, Rafael Santos Torroella u. Lutz W. Löpsinger (Einführung und Katalog): Salvador Dali (1904–1989), Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Verlag Gerd Hatje (1989), ISBN 978 3775702751, S. 496: "Es enthält einige der besten Photographien Dalís, Aufnahmen, die nach seinen eigenen Anweisungen entstanden."

- ^ British Journal of Photography. Henry Greenwood & Company, Limited. April 1994..

- ^ Callahan, Sean (1985). American Photographer. CBS Publications. pp. 94, vol. 15.

- ^ Bonhams auction house: Salvador Dali and Philippe Halsman Dali's Mustache: A Photographic Interview, Simon and Schuster, New York (1954).

- ^ a b c Michael Elsohn Ross (2003). Salvador Dalí and the Surrealists: Their Lives and Ideas: 21 Activities. Chicago Review Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-1556524790.

- ^ a b Morris, Desmond (2012). The Naked Man: A Study of the Male Body. Random House. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-1409075721.

- ^ Tampa Bay Magazine. Tampa Bay Publications, Inc. November–December 1991. p. 9. ISSN 1070-3845.

- ^ Vita of Salvador Dalí i Domènech, Fondation Gala-Salvador Dalí.

- ^ a b c Capitaine Peter Moore; Catherine Moore (2009). Flagrant Dali. Grasset. p. 47. ISBN 978-2246732495.

- ^ "Photograph: Gala und Dalí (1933)".

- ^ "Philippe Halsman: Salvador Dalí in New York (1942)". Archived from the original on November 24, 2015.

- ^ Irving Penn: Salvador Dali (1947).

- ^ Alfredo Valente: Salvador Dali (ca. 1950).

- ^ Philippe Halsman: Salvador Dalí (etwa 1954) Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Otte, Torsten (2006). Salvador Dalí: eine Biographie mit Selbstzeugnissen des Künstlers. Königshausen & Neumann. p. 104. ISBN 978-3826033063.

- ^ a b Video: Salvador Dalí Reveals the Secrets of His Trademark Moustache (1954) in der US-Fernsehshow The Name's the Same.

- ^ Pivot, Bernard (2011). Les Mots de ma vie. Albin Michel. p. 43. ISBN 978-2226229274.

- ^ Salvador Dalí; Elliott H. King; David A. Brennan; Montse Aguer Teixidor; William Jeffett; Hank Hine; Montserrat Aguer; Charles Hine (2010). Salvador Dalí: The Late Work. High Museum of Art. pp. 120, 126, 130. ISBN 978-0300168280.

- ^ "Movember poll finds Salvador Dali had most famous moustache". The Telegraph, 3 November 2010; retrieved 2015-11-21.

- ^ Jay Robert Nash (1982). Zanies: The World's Greatest Eccentrics. M. Evans. p. 102. ISBN 978-1590775226.

- ^ a b Rothman, Roger (2012). Tiny Surrealism: Salvador Dalí and the Aesthetics of the Small. University of Nebraska Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0803236493.

- ^ New York Media, LLC (11 July 1994). "New York". Newyorkmetro.com. New York Media, LLC: 44. ISSN 0028-7369.

- ^ Cowles, Fleur (1960). The Case of Salvador Dali. Little, Brown. p. 296.

- ^ New York Media, LLC (22 November 1993). "New York". Newyorkmetro.com. New York Media, LLC: 76. ISSN 0028-7369.

- ^ Mary Ann Caws (2009). Salvador Dalí. Reaktion Books. p. 63. ISBN 978-1861896278.

- ^ Stein, Gertrude (2013). Everybody's Autobiography. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0307829771.

- ^ "Helmut Newton: Salvador Dalí (1986)".

- ^ Rob White; Edward Buscombe (2003). British Film Institute Film Classics. Taylor & Francis. p. 120. ISBN 978-1579583286.

- ^ Luis Buñuel; Garrett White (2002). An Unspeakable Betrayal: Selected Writings of Luis Buñuel. University of California Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0520234239.

- ^ Román Gubern; Paul Hammond (2012). Luis Buñuel: The Red Years, 1929–1939. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0299284732.

- ^ Jean-François Guédon; Hélène Sorez (2011). Citations de culture générale expliquées. Eyrolles. p. 140. ISBN 978-2212862584.

- ^ Nuridsany, Michel (2004). Dalí. Flammarion. p. 177. ISBN 978-2080682222.

- ^ Descharnes, Robert (1984). Salvador Dali: The Work, the Man. H.N. Abrams. p. 291. ISBN 978-0810908253.

- ^ Jonathan Jones (21 January 2006). "Of misfits and kings". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- ^ Clifford Thurlow; Carlos Lozano (2000). Sex, Surrealism, Dali and Me: The Memoirs of Carlos Lozano. Maximilian Thurlow. p. 65. ISBN 978-0953820504.

- ^ Henri-François Rey (1974). Dali dans son labyrinthe. Grasset. p. 15. ISBN 978-2246800057.

- ^ R. A. Stradling, Philip IV and the Government of Spain, 1621–1665. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1988, ISBN 0521323339, p. 84.

- ^ Antonio Pitxot; Montserrat Aguer (2008). Salvador Dalí House-Museum: Portlligat-Cadaqués. Triangle Postals. ISBN 978-8484783619.

- ^ Salvador Dalí; Jack J. Spector (2006). La vie secrète de Salvador Dali: suis-je un génie? : édition critique des manuscrits originaux de La vie secrète de Salvador Dalii. l'Age d'Homme. p. 188. ISBN 978-2825136430.

- ^ Magazine littéraire. Magazine littéraire. 2004.

- ^ Philip Sweeney: Arts: "Don't talk to me about the Sixties", The Independent, 23. October 2011; retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ Jean Marie Pérrier: Dalí and Françoise Hardy Archived 2018-08-14 at the Wayback Machine, October 1968.

- ^ Salvador Dalí: Unabhängigkeitserklärung der Phantasie und Erklärung der Rechte des Menschen auf seine Verrücktheit, Gesammelte Schriften Archived 2015-11-23 at the Wayback Machine, Rogner & Bernhard, München (1974), ISBN 978-3807700793.

- ^ Timeline – A Century of Salvador Dali, Website of the Salvador Dalí Museum in Saint Petersburg/FL.

- ^ "Dalí's mustache" on a tourist website; retrieved 2015-11-22.

- ^ Ad campaign for the Civita Art School: Baby Dali – Artists born here Archived 2015-11-24 at the Wayback Machine, by Yes I AM, Rome, Italy.

- ^ Görgün, Kenan (2005). L'Enfer est à nous. Quadrature. p. 10. ISBN 978-2960050608.

External links

[edit]- Halsman′s photographs of Salvador Dalí (Magnum Photos). Not all shown photographs were used in Dali's Mustache. The Website displays both versions of the modified Mona Lisa – gold coins/Halsman's hands and dollar bills/Dalí's hands. The photograph with the slice of Gruyère is not shown.