Cutzinas

| Cutzinas | |

|---|---|

| Chieftain of the Mastraciani (?) | |

| Reign | before 534 – 563 |

| Died | January 563 |

Cutzinas or Koutzinas (Greek: Κουτζίνας) was a Berber tribal leader who played a major role in the wars of the East Roman or Byzantine Empire against the Berber tribes in Africa in the middle of the 6th century, fighting both against and for the Byzantines. A staunch Byzantine ally during the latter stages of the Berber rebellion, he remained an imperial vassal until his murder in 563 by the new Byzantine governor.

Life

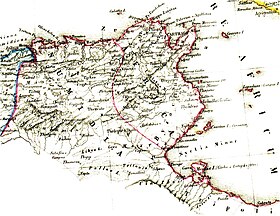

[edit]Cutzinas was of mixed stock: his father was a Berber, while his mother came from the Roman population of North Africa.[1] Following the reconquest of North Africa by the East Roman (Byzantine) Empire in the Vandalic War (533–534), several uprisings by the native Berber tribes occurred in the North African provinces. Cutzinas is mentioned by the eyewitness historian Procopius of Caesarea as one of the leaders of the rebellion in the province of Byzacena, alongside Esdilasas, Medisinissas and Iourphouthes. In spring 535, however, the rebels were defeated by the Byzantine military commander Solomon in the battles of Mammes and Mount Bourgaon, and Cutzinas was forced to flee west to Mount Aurasium in Numidia, where he sought the protection of the local Berber ruler, Iaudas.[2][3]

Cutzinas disappears from the record until 544, by which time, according to the epic poem Iohannis of the Roman African writer Flavius Cresconius Corippus, he was an ally of the Byzantines and a friend of Solomon.[1] In that year, the Berber rebellion, suppressed by Solomon after his pacification of the tribes of Mount Aurasium in 540, flared up again in Tripolitania and quickly spread to Byzacena, where the Berbers rose up under the leadership of Antalas.[4][5] This time, Cutzinas opposed the revolt, and brought his own people, the "Mastraciani" (the reading of the name is uncertain) on the side of the Byzantine military.[6]

In 544, Solomon was killed in battle, and over the next year the Byzantine position in Africa crumbled before the rebels.[5] In late 545, Cutzinas and Iaudas joined Antalas in a march against Carthage, the capital and main stronghold of the Byzantine government in Africa. Cutzinas secretly agreed with the Byzantine governor, Areobindus, to betray Antalas, when battle was joined; Areobindus, however, revealed this to Guntharis, a Byzantine commander who was in turn in contact with Antalas and planned to betray Areobindus himself. To gain time to prepare, Guntharis advised Areobindus to take Cutzinas' children hostage; in the event Guntharis launched an uprising in Carthage which the thoroughly unwarlike Areobindus failed to suppress, resulting in his execution and the usurpation of the governorship by Guntharis.[7] After his plans were revealed by Guntharis to Antalas, Cutzinas changed sides once more and allied himself with Guntharis, giving his mother and son as hostages. Along with the Armenian commander Artabanes, he was sent to pursue Antalas, scoring a victory over the rebel forces near Hadrumetum.[8]

In winter 546/7, when the new Byzantine governor and commander-in-chief, John Troglita, arrived in Africa, Cutzinas and his followers joined him, and participated in the expedition that saw the defeat and submission of Antalas.[9] Shortly after, Cutzinas received the supreme Roman military rank of magister militum from Troglita. In the summer of 547 Cutzinas accompanied Troglita in his campaign against the Tripolitanian tribes under Carcasan. Before the Battle of Marta he advocated attacking the rebel forces, but the Byzantine army was heavily defeated by Carcasan and Antalas, who had once more risen in revolt.[10][11] In the same winter, Cutzinas quarreled with another pro-Byzantine Berber leader, Ifisdaias. Their dispute threatened to spill over into open armed conflict, but the intervention of Troglita prevented this and the official John effected a reconciliation between the two.[12]

In spring 548, he participated once more in Troglita's campaign, according to Corippus at the head of no less than 30,000 men, divided into units a thousand strong under a Berber dux each. This number possibly also includes Byzantine troops placed under Cutzinas' command as well.[9] During the campaign, Cutzinas and the other Berber leaders were crucial in suppressing a near-mutiny of the Byzantine troops due to Antalas' scorched earth strategy. The Berbers' steadfast support enabled Troglita to overcome the crisis and lead his army against the forces of Carcasan and Antalas. Cutzinas fought in the ensuing Battle of the Fields of Cato, which was a decisive Byzantine victory: Carcasan fell, and the Berber revolt was crushed as Antalas and the surviving leaders submitted to Troglita.[11][13]

After this, Cutzinas remained as a vassal chieftain, receiving regular pay from the Byzantine authorities. In January 563, however, the new prefect of Africa, John Rogathinus, refused to hand over the money and had Cutzinas murdered, prompting an uprising from the latter's children.[14]

See also

[edit]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, p. 366.

- ^ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, pp. 366, 1170–1171.

- ^ Bury 1958, pp. 140–141, 143.

- ^ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, p. 1175.

- ^ a b Bury 1958, p. 145.

- ^ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, pp. 366–367.

- ^ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, pp. 108–109, 367.

- ^ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, pp. 126, 367.

- ^ a b Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, p. 367.

- ^ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, pp. 367, 647–648.

- ^ a b Bury 1958, p. 147.

- ^ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, p. 367; 613.

- ^ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, pp. 367–368, 648–649.

- ^ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, p. 368.

Sources

[edit]- Bury, John Bagnell (1958). History of the Later Roman Empire: From the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian, Volume 2. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-20399-9.

- Martindale, John Robert; Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin; Morris, J., eds. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Volume III: A.D. 527–641. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20160-5.