Curvature

In mathematics, curvature is any of several strongly related concepts in geometry that intuitively measure the amount by which a curve deviates from being a straight line or by which a surface deviates from being a plane. If a curve or surface is contained in a larger space, curvature can be defined extrinsically relative to the ambient space. Curvature of Riemannian manifolds of dimension at least two can be defined intrinsically without reference to a larger space.

For curves, the canonical example is that of a circle, which has a curvature equal to the reciprocal of its radius. Smaller circles bend more sharply, and hence have higher curvature. The curvature at a point of a differentiable curve is the curvature of its osculating circle — that is, the circle that best approximates the curve near this point. The curvature of a straight line is zero. In contrast to the tangent, which is a vector quantity, the curvature at a point is typically a scalar quantity, that is, it is expressed by a single real number.

For surfaces (and, more generally for higher-dimensional manifolds), that are embedded in a Euclidean space, the concept of curvature is more complex, as it depends on the choice of a direction on the surface or manifold. This leads to the concepts of maximal curvature, minimal curvature, and mean curvature.

History

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2019) |

In Tractatus de configurationibus qualitatum et motuum,[1] the 14th-century philosopher and mathematician Nicole Oresme introduces the concept of curvature as a measure of departure from straightness; for circles he has the curvature as being inversely proportional to the radius; and he attempts to extend this idea to other curves as a continuously varying magnitude.[2]

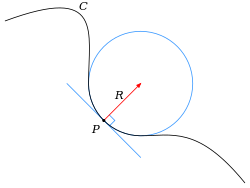

The curvature of a differentiable curve was originally defined through osculating circles. In this setting, Augustin-Louis Cauchy showed that the center of curvature is the intersection point of two infinitely close normal lines to the curve.[3] curve

Plane curves

[edit]Intuitively, the curvature describes for any part of a curve how much the curve direction changes over a small distance travelled (e.g. angle in rad/m), so it is a measure of the instantaneous rate of change of direction of a point that moves on the curve: the larger the curvature, the larger this rate of change. In other words, the curvature measures how fast the unit tangent vector to the curve at point p rotates[4] when point p moves at unit speed along the curve. In fact, it can be proved that this instantaneous rate of change is exactly the curvature. More precisely, suppose that the point is moving on the curve at a constant speed of one unit, that is, the position of the point P(s) is a function of the parameter s, which may be thought as the time or as the arc length from a given origin. Let T(s) be a unit tangent vector of the curve at P(s), which is also the derivative of P(s) with respect to s. Then, the derivative of T(s) with respect to s is a vector that is normal to the curve and whose length is the curvature.

To be meaningful, the definition of the curvature and its different characterizations require that the curve is continuously differentiable near P, for having a tangent that varies continuously; it requires also that the curve is twice differentiable at P, for insuring the existence of the involved limits, and of the derivative of T(s).

The characterization of the curvature in terms of the derivative of the unit tangent vector is probably less intuitive than the definition in terms of the osculating circle, but formulas for computing the curvature are easier to deduce. Therefore, and also because of its use in kinematics, this characterization is often given as a definition of the curvature.

Osculating circle

[edit]

Historically, the curvature of a differentiable curve was defined through the osculating circle, which is the circle that best approximates the curve at a point. More precisely, given a point P on a curve, every other point Q of the curve defines a circle (or sometimes a line) passing through Q and tangent to the curve at P. The osculating circle is the limit, if it exists, of this circle when Q tends to P. Then the center and the radius of curvature of the curve at P are the center and the radius of the osculating circle. The curvature is the reciprocal of radius of curvature. That is, the curvature is

where R is the radius of curvature[5] (the whole circle has this curvature, it can be read as turn 2π over the length 2πR).

This definition is difficult to manipulate and to express in formulas. Therefore, other equivalent definitions have been introduced.

In terms of arc-length parametrization

[edit]Every differentiable curve can be parametrized with respect to arc length.[6] In the case of a plane curve, this means the existence of a parametrization γ(s) = (x(s), y(s)), where x and y are real-valued differentiable functions whose derivatives satisfy

This means that the tangent vector

has a length equal to one and is thus a unit tangent vector.

If the curve is twice differentiable, that is, if the second derivatives of x and y exist, then the derivative of T(s) exists. This vector is normal to the curve, its length is the curvature κ(s), and it is oriented toward the center of curvature. That is,

Moreover, because the radius of curvature is (assuming 𝜿(s) ≠ 0)

and the center of curvature is on the normal to the curve, the center of curvature is the point

(In case the curvature is zero, the center of curvature is not located anywhere on the plane R2 and is often said to be located "at infinity".)

If N(s) is the unit normal vector obtained from T(s) by a counterclockwise rotation of π/2, then

with k(s) = ± κ(s). The real number k(s) is called the oriented curvature or signed curvature. It depends on both the orientation of the plane (definition of counterclockwise), and the orientation of the curve provided by the parametrization. In fact, the change of variable s → –s provides another arc-length parametrization, and changes the sign of k(s).

In terms of a general parametrization

[edit]Let γ(t) = (x(t), y(t)) be a proper parametric representation of a twice differentiable plane curve. Here proper means that on the domain of definition of the parametrization, the derivative dγ/dt is defined, differentiable and nowhere equal to the zero vector.

With such a parametrization, the signed curvature is

where primes refer to derivatives with respect to t. The curvature κ is thus

These can be expressed in a coordinate-free way as

These formulas can be derived from the special case of arc-length parametrization in the following way. The above condition on the parametrisation imply that the arc length s is a differentiable monotonic function of the parameter t, and conversely that t is a monotonic function of s. Moreover, by changing, if needed, s to –s, one may suppose that these functions are increasing and have a positive derivative. Using notation of the preceding section and the chain rule, one has

and thus, by taking the norm of both sides

where the prime denotes differentiation with respect to t.

The curvature is the norm of the derivative of T with respect to s. By using the above formula and the chain rule this derivative and its norm can be expressed in terms of γ′ and γ″ only, with the arc-length parameter s completely eliminated, giving the above formulas for the curvature.

Graph of a function

[edit]The graph of a function y = f(x), is a special case of a parametrized curve, of the form

As the first and second derivatives of x are 1 and 0, previous formulas simplify to

for the curvature, and to

for the signed curvature.

In the general case of a curve, the sign of the signed curvature is somewhat arbitrary, as it depends on the orientation of the curve. In the case of the graph of a function, there is a natural orientation by increasing values of x. This makes significant the sign of the signed curvature.

The sign of the signed curvature is the same as the sign of the second derivative of f. If it is positive then the graph has an upward concavity, and, if it is negative the graph has a downward concavity. If it is zero, then one has an inflection point or an undulation point.

When the slope of the graph (that is the derivative of the function) is small, the signed curvature is well approximated by the second derivative. More precisely, using big O notation, one has

It is common in physics and engineering to approximate the curvature with the second derivative, for example, in beam theory or for deriving the wave equation of a string under tension, and other applications where small slopes are involved. This often allows systems that are otherwise nonlinear to be treated approximately as linear.

Polar coordinates

[edit]If a curve is defined in polar coordinates by the radius expressed as a function of the polar angle, that is r is a function of θ, then its curvature is

where the prime refers to differentiation with respect to θ.

This results from the formula for general parametrizations, by considering the parametrization

Implicit curve

[edit]For a curve defined by an implicit equation F(x, y) = 0 with partial derivatives denoted Fx , Fy , Fxx , Fxy , Fyy , the curvature is given by[7]

The signed curvature is not defined, as it depends on an orientation of the curve that is not provided by the implicit equation. Note that changing F into –F would not change the curve defined by F(x, y) = 0, but it would change the sign of the numerator if the absolute value were omitted in the preceding formula.

A point of the curve where Fx = Fy = 0 is a singular point, which means that the curve is not differentiable at this point, and thus that the curvature is not defined (most often, the point is either a crossing point or a cusp).

The above formula for the curvature can be derived from the expression of the curvature of the graph of a function by using the implicit function theorem and the fact that, on such a curve, one has

Examples

[edit]It can be useful to verify on simple examples that the different formulas given in the preceding sections give the same result.

Circle

[edit]A common parametrization of a circle of radius r is γ(t) = (r cos t, r sin t). The formula for the curvature gives

It follows, as expected, that the radius of curvature is the radius of the circle, and that the center of curvature is the center of the circle.

The circle is a rare case where the arc-length parametrization is easy to compute, as it is

It is an arc-length parametrization, since the norm of

is equal to one. This parametrization gives the same value for the curvature, as it amounts to division by r3 in both the numerator and the denominator in the preceding formula.

The same circle can also be defined by the implicit equation F(x, y) = 0 with F(x, y) = x2 + y2 – r2. Then, the formula for the curvature in this case gives

Parabola

[edit]Consider the parabola y = ax2 + bx + c.

It is the graph of a function, with derivative 2ax + b, and second derivative 2a. So, the signed curvature is

It has the sign of a for all values of x. This means that, if a > 0, the concavity is upward directed everywhere; if a < 0, the concavity is downward directed; for a = 0, the curvature is zero everywhere, confirming that the parabola degenerates into a line in this case.

The (unsigned) curvature is maximal for x = –b/2a, that is at the stationary point (zero derivative) of the function, which is the vertex of the parabola.

Consider the parametrization γ(t) = (t, at2 + bt + c) = (x, y). The first derivative of x is 1, and the second derivative is zero. Substituting into the formula for general parametrizations gives exactly the same result as above, with x replaced by t. If we use primes for derivatives with respect to the parameter t.

The same parabola can also be defined by the implicit equation F(x, y) = 0 with F(x, y) = ax2 + bx + c – y. As Fy = –1, and Fyy = Fxy = 0, one obtains exactly the same value for the (unsigned) curvature. However, the signed curvature is meaningless here, as –F(x, y) = 0 is a valid implicit equation for the same parabola, which gives the opposite sign for the curvature.

Frenet–Serret formulas for plane curves

[edit]

The expression of the curvature In terms of arc-length parametrization is essentially the first Frenet–Serret formula

where the primes refer to the derivatives with respect to the arc length s, and N(s) is the normal unit vector in the direction of T′(s).

As planar curves have zero torsion, the second Frenet–Serret formula provides the relation

For a general parametrization by a parameter t, one needs expressions involving derivatives with respect to t. As these are obtained by multiplying by ds/dt the derivatives with respect to s, one has, for any proper parametrization

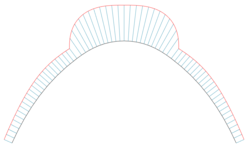

Curvature comb

[edit]

A curvature comb[8] can be used to represent graphically the curvature of every point on a curve. If is a parametrised curve its comb is defined as the parametrized curve

where are the curvature and normal vector and is a scaling factor (to be chosen as to enhance the graphical representation).

Space curves

[edit]

As in the case of curves in two dimensions, the curvature of a regular space curve C in three dimensions (and higher) is the magnitude of the acceleration of a particle moving with unit speed along a curve. Thus if γ(s) is the arc-length parametrization of C then the unit tangent vector T(s) is given by

and the curvature is the magnitude of the acceleration:

The direction of the acceleration is the unit normal vector N(s), which is defined by

The plane containing the two vectors T(s) and N(s) is the osculating plane to the curve at γ(s). The curvature has the following geometrical interpretation. There exists a circle in the osculating plane tangent to γ(s) whose Taylor series to second order at the point of contact agrees with that of γ(s). This is the osculating circle to the curve. The radius of the circle R(s) is called the radius of curvature, and the curvature is the reciprocal of the radius of curvature:

The tangent, curvature, and normal vector together describe the second-order behavior of a curve near a point. In three dimensions, the third-order behavior of a curve is described by a related notion of torsion, which measures the extent to which a curve tends to move as a helical path in space. The torsion and curvature are related by the Frenet–Serret formulas (in three dimensions) and their generalization (in higher dimensions).

General expressions

[edit]For a parametrically-defined space curve in three dimensions given in Cartesian coordinates by γ(t) = (x(t), y(t), z(t)), the curvature is

where the prime denotes differentiation with respect to the parameter t. This can be expressed independently of the coordinate system by means of the formula[9]

where × denotes the vector cross product. The following formula is valid for the curvature of curves in a Euclidean space of any dimension:

Curvature from arc and chord length

[edit]Given two points P and Q on C, let s(P,Q) be the arc length of the portion of the curve between P and Q and let d(P,Q) denote the length of the line segment from P to Q. The curvature of C at P is given by the limit[citation needed]

where the limit is taken as the point Q approaches P on C. The denominator can equally well be taken to be d(P,Q)3. The formula is valid in any dimension. Furthermore, by considering the limit independently on either side of P, this definition of the curvature can sometimes accommodate a singularity at P. The formula follows by verifying it for the osculating circle.

Surfaces

[edit]The curvature of curves drawn on a surface is the main tool for the defining and studying the curvature of the surface.

Curves on surfaces

[edit]For a curve drawn on a surface (embedded in three-dimensional Euclidean space), several curvatures are defined, which relates the direction of curvature to the surface's unit normal vector, including the:

Any non-singular curve on a smooth surface has its tangent vector T contained in the tangent plane of the surface. The normal curvature, kn, is the curvature of the curve projected onto the plane containing the curve's tangent T and the surface normal u; the geodesic curvature, kg, is the curvature of the curve projected onto the surface's tangent plane; and the geodesic torsion (or relative torsion), τr, measures the rate of change of the surface normal around the curve's tangent.

Let the curve be arc-length parametrized, and let t = u × T so that T, t, u form an orthonormal basis, called the Darboux frame. The above quantities are related by:

Principal curvature

[edit]

All curves on the surface with the same tangent vector at a given point will have the same normal curvature, which is the same as the curvature of the curve obtained by intersecting the surface with the plane containing T and u. Taking all possible tangent vectors, the maximum and minimum values of the normal curvature at a point are called the principal curvatures, k1 and k2, and the directions of the corresponding tangent vectors are called principal normal directions.

Normal sections

[edit]Curvature can be evaluated along surface normal sections, similar to § Curves on surfaces above (see for example the Earth radius of curvature).

Developable surfaces

[edit]Some curved surfaces, such as those made from a smooth sheet of paper, can be flattened down into the plane without distorting their intrinsic features in any way. Such developable surfaces have zero Gaussian curvature (see below).[10]

Gaussian curvature

[edit]In contrast to curves, which do not have intrinsic curvature, but do have extrinsic curvature (they only have a curvature given an embedding), surfaces can have intrinsic curvature, independent of an embedding. The Gaussian curvature, named after Carl Friedrich Gauss, is equal to the product of the principal curvatures, k1k2. It has a dimension of length−2 and is positive for spheres, negative for one-sheet hyperboloids and zero for planes and cylinders. It determines whether a surface is locally convex (when it is positive) or locally saddle-shaped (when it is negative).

Gaussian curvature is an intrinsic property of the surface, meaning it does not depend on the particular embedding of the surface; intuitively, this means that ants living on the surface could determine the Gaussian curvature. For example, an ant living on a sphere could measure the sum of the interior angles of a triangle and determine that it was greater than 180 degrees, implying that the space it inhabited had positive curvature. On the other hand, an ant living on a cylinder would not detect any such departure from Euclidean geometry; in particular the ant could not detect that the two surfaces have different mean curvatures (see below), which is a purely extrinsic type of curvature.

Formally, Gaussian curvature only depends on the Riemannian metric of the surface. This is Gauss's celebrated Theorema Egregium, which he found while concerned with geographic surveys and mapmaking.

An intrinsic definition of the Gaussian curvature at a point P is the following: imagine an ant which is tied to P with a short thread of length r. It runs around P while the thread is completely stretched and measures the length C(r) of one complete trip around P. If the surface were flat, the ant would find C(r) = 2πr. On curved surfaces, the formula for C(r) will be different, and the Gaussian curvature K at the point P can be computed by the Bertrand–Diguet–Puiseux theorem as

The integral of the Gaussian curvature over the whole surface is closely related to the surface's Euler characteristic; see the Gauss–Bonnet theorem.

The discrete analog of curvature, corresponding to curvature being concentrated at a point and particularly useful for polyhedra, is the (angular) defect; the analog for the Gauss–Bonnet theorem is Descartes' theorem on total angular defect.

Because (Gaussian) curvature can be defined without reference to an embedding space, it is not necessary that a surface be embedded in a higher-dimensional space in order to be curved. Such an intrinsically curved two-dimensional surface is a simple example of a Riemannian manifold.

Mean curvature

[edit]The mean curvature is an extrinsic measure of curvature equal to half the sum of the principal curvatures, k1 + k2/2. It has a dimension of length−1. Mean curvature is closely related to the first variation of surface area. In particular, a minimal surface such as a soap film has mean curvature zero and a soap bubble has constant mean curvature. Unlike Gauss curvature, the mean curvature is extrinsic and depends on the embedding, for instance, a cylinder and a plane are locally isometric but the mean curvature of a plane is zero while that of a cylinder is nonzero.

Second fundamental form

[edit]The intrinsic and extrinsic curvature of a surface can be combined in the second fundamental form. This is a quadratic form in the tangent plane to the surface at a point whose value at a particular tangent vector X to the surface is the normal component of the acceleration of a curve along the surface tangent to X; that is, it is the normal curvature to a curve tangent to X (see above). Symbolically,

where N is the unit normal to the surface. For unit tangent vectors X, the second fundamental form assumes the maximum value k1 and minimum value k2, which occur in the principal directions u1 and u2, respectively. Thus, by the principal axis theorem, the second fundamental form is

Thus the second fundamental form encodes both the intrinsic and extrinsic curvatures.

Shape operator

[edit]An encapsulation of surface curvature can be found in the shape operator, S, which is a self-adjoint linear operator from the tangent plane to itself (specifically, the differential of the Gauss map).

For a surface with tangent vectors X and normal N, the shape operator can be expressed compactly in index summation notation as

(Compare the alternative expression of curvature for a plane curve.)

The Weingarten equations give the value of S in terms of the coefficients of the first and second fundamental forms as

The principal curvatures are the eigenvalues of the shape operator, the principal curvature directions are its eigenvectors, the Gauss curvature is its determinant, and the mean curvature is half its trace.

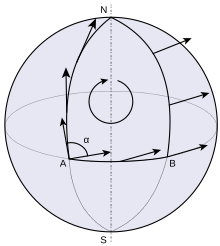

Curvature of space

[edit]By extension of the former argument, a space of three or more dimensions can be intrinsically curved. The curvature is intrinsic in the sense that it is a property defined at every point in the space, rather than a property defined with respect to a larger space that contains it. In general, a curved space may or may not be conceived as being embedded in a higher-dimensional ambient space; if not then its curvature can only be defined intrinsically.

After the discovery of the intrinsic definition of curvature, which is closely connected with non-Euclidean geometry, many mathematicians and scientists questioned whether ordinary physical space might be curved, although the success of Euclidean geometry up to that time meant that the radius of curvature must be astronomically large. In the theory of general relativity, which describes gravity and cosmology, the idea is slightly generalised to the "curvature of spacetime"; in relativity theory spacetime is a pseudo-Riemannian manifold. Once a time coordinate is defined, the three-dimensional space corresponding to a particular time is generally a curved Riemannian manifold; but since the time coordinate choice is largely arbitrary, it is the underlying spacetime curvature that is physically significant.

Although an arbitrarily curved space is very complex to describe, the curvature of a space which is locally isotropic and homogeneous is described by a single Gaussian curvature, as for a surface; mathematically these are strong conditions, but they correspond to reasonable physical assumptions (all points and all directions are indistinguishable). A positive curvature corresponds to the inverse square radius of curvature; an example is a sphere or hypersphere. An example of negatively curved space is hyperbolic geometry (see also: non-positive curvature). A space or space-time with zero curvature is called flat. For example, Euclidean space is an example of a flat space, and Minkowski space is an example of a flat spacetime. There are other examples of flat geometries in both settings, though. A torus or a cylinder can both be given flat metrics, but differ in their topology. Other topologies are also possible for curved space .

Generalizations

[edit]

The mathematical notion of curvature is also defined in much more general contexts.[11] Many of these generalizations emphasize different aspects of the curvature as it is understood in lower dimensions.

One such generalization is kinematic. The curvature of a curve can naturally be considered as a kinematic quantity, representing the force felt by a certain observer moving along the curve; analogously, curvature in higher dimensions can be regarded as a kind of tidal force (this is one way of thinking of the sectional curvature). This generalization of curvature depends on how nearby test particles diverge or converge when they are allowed to move freely in the space; see Jacobi field.

Another broad generalization of curvature comes from the study of parallel transport on a surface. For instance, if a vector is moved around a loop on the surface of a sphere keeping parallel throughout the motion, then the final position of the vector may not be the same as the initial position of the vector. This phenomenon is known as holonomy.[12] Various generalizations capture in an abstract form this idea of curvature as a measure of holonomy; see curvature form. A closely related notion of curvature comes from gauge theory in physics, where the curvature represents a field and a vector potential for the field is a quantity that is in general path-dependent: it may change if an observer moves around a loop.

Two more generalizations of curvature are the scalar curvature and Ricci curvature. In a curved surface such as the sphere, the area of a disc on the surface differs from the area of a disc of the same radius in flat space. This difference (in a suitable limit) is measured by the scalar curvature. The difference in area of a sector of the disc is measured by the Ricci curvature. Each of the scalar curvature and Ricci curvature are defined in analogous ways in three and higher dimensions. They are particularly important in relativity theory, where they both appear on the side of Einstein's field equations that represents the geometry of spacetime (the other side of which represents the presence of matter and energy). These generalizations of curvature underlie, for instance, the notion that curvature can be a property of a measure; see curvature of a measure.

Another generalization of curvature relies on the ability to compare a curved space with another space that has constant curvature. Often this is done with triangles in the spaces. The notion of a triangle makes senses in metric spaces, and this gives rise to CAT(k) spaces.

See also

[edit]- Curvature form for the appropriate notion of curvature for vector bundles and principal bundles with connection

- Curvature of a measure for a notion of curvature in measure theory

- Curvature of parametric surfaces

- Curvature of Riemannian manifolds for generalizations of Gauss curvature to higher-dimensional Riemannian manifolds

- Curvature vector and geodesic curvature for appropriate notions of curvature of curves in Riemannian manifolds, of any dimension

- Degree of curvature

- Differential geometry of curves for a full treatment of curves embedded in a Euclidean space of arbitrary dimension

- Dioptre, a measurement of curvature used in optics

- Evolute, the locus of the centers of curvature of a given curve

- Fundamental theorem of curves

- Gauss–Bonnet theorem for an elementary application of curvature

- Gauss map for more geometric properties of Gauss curvature

- Gauss's principle of least constraint, an expression of the Principle of Least Action

- Mean curvature at one point on a surface

- Minimum railway curve radius

- Radius of curvature

- Second fundamental form for the extrinsic curvature of hypersurfaces in general

- Sinuosity

- Torsion of a curve

Notes

[edit]- ^ Clagett, Marshall (1968), Nicole Oresme and the Medieval Geometry of Qualities and Motions, Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 978-0-299-04880-8

- ^ Serrano, Isabel M.; Suceavă, Bogdan D. (2015), "A Medieval Mystery: Nicole Oresme's Concept of Curvitas", Notices of the AMS, 62 (9): 1030–1034, doi:10.1090/noti1275

- ^ Borovik, Alexandre; Katz, Mikhail G. (2011), "Who Gave You the Cauchy–Weierstrass Tale? The Dual History of Rigorous Calculus", Foundations of Science, 17 (3): 245–276, arXiv:1108.2885, doi:10.1007/s10699-011-9235-x

- ^ Pressley, Andrew (2001), Elementary Differential Geometry, London: Springer, p. 29, ISBN 978-1-85233-152-8

- ^ Kline 1998, p. 458

- ^ Kennedy, John (2011), The Arc Length Parametrization of a Curve (Website), archived from the original on 2015-09-28, retrieved 2013-12-10

- ^ Goldman, Ron (2005), "Curvature formulas for implicit curves and surfaces", Computer Aided Geometric Design, 22 (7): 632–658, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.413.3008, doi:10.1016/j.cagd.2005.06.005

- ^ Farin, Gerald (Nov 2016), "Curvature combs and curvature plots", Computer-Aided Design, 80: 6–8, doi:10.1016/j.cad.2016.08.003

- ^ A proof of this can be found at the article on curvature at Wolfram MathWorld.

- ^ developable surface, Mathworld. (Retrieved 11 February 2021)

- ^ Kobayashi, Shōshichi; Nomizu, Katsumi (1963), "2–3", Foundations of Differential Geometry, New York: Interscience, ISBN 978-0-470-49647-3

- ^ Henderson, David W.; Taimin̦a, Daina (2005), Experiencing Geometry: Euclidean and Non-Euclidean with History (3rd ed.), Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, pp. 98–99, doi:10.3792/euclid/9781429799850, ISBN 978-0-13-143748-7

References

[edit]- Coolidge, Julian L. (Jun 1952), "The Unsatisfactory Story of Curvature", American Mathematical Monthly, 59 (6): 375–379, doi:10.2307/2306807, JSTOR 2306807

- Sokolov, Dmitriĭ Dmitrievich (2001) [1994], "Curvature", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press

- Kline, Morris (1998), Calculus: An Intuitive and Physical Approach (2nd ed.), Mineola, NY: Dover, pp. 457–461, ISBN 978-0-486-40453-0 (restricted online copy, p. 457, at Google Books)

- Klaf, A. Albert (1956), Calculus Refresher, Dover, pp. 151–168, ISBN 978-0-486-20370-6 (restricted online copy , p. 151, at Google Books)

- Casey, James (1996), Exploring Curvature, Vieweg Mathematics, Braunschweig: Vieweg, ISBN 978-3-528-06475-4

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\mathbf {T} (s)&={\boldsymbol {\gamma }}'(s),\\[8mu]\|\mathbf {T} (s)\|^{2}&=1\ {\text{(constant)}}\implies \mathbf {T} '(s)\cdot \mathbf {T} (s)=0,\\[5mu]\kappa (s)&=\|\mathbf {T} '(s)\|=\|{\boldsymbol {\gamma }}''(s)\|={\sqrt {x''(s)^{2}+y''(s)^{2}}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d3e394b73f1bf429d6f048507f4a8707cf8790fd)