Cultural depictions of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

Maximilian I (22 March 1459 – 12 January 1519) was Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death.

Maximilian was an ambitious leader who was active in many fields and lived in a time of great upheaval between the Medieval and Early Modern worlds. Maximilian's reputation in historiography is many-sided, often contradictory: the last knight or the first modern foot soldier and "first cannoneer of his nation";[1][2] the first Renaissance prince (understood either as a Machiavellian politician[3] or omnicompetent, universal genius[4]) or a dilettante;[5] a far-sighted state builder and reformer, or an unrealistic schemer whose posthumous successes were based on luck,[6] or a clear-headed, prudent statesman.[7] While Austrian researchers often emphasize his role as the founder of the early modern supremacy of the House of Habsburg or founder of the nation,[8] debates on Maximilian's political activities in Germany as well as international scholarship on his reign as Holy Roman Emperor often centre on the Imperial Reform. In the Burgundian Low Countries (and the modern Netherlands and Belgium), in scholarly circles as well as popular imagination, his depictions vary as well: a foreign tyrant who imposed wars, taxes, high-handed methods of ruling and suspicious personal agenda, and then "abandoned" the Low Countries after gaining the imperial throne, or a saviour and builder of the early modern state. Jelle Haemers calls the relationship between the Low Countries and Maximilian "a troubled marriage".[9][10]

In his lifetime, as the first ruler who exploited the propaganda potential of the printing press,[11] he attempted to control his own depictions, although various projects (called Gedechtnus) that he commissioned (and authored in part by him in some cases) were only finished after his death. Various authors refer to the emperor's image-building programs as "unprecedented".[12][13][14] Historian Thomas Brady Jr. remarks that Maximilian's humanists, artists, and printers "created for him a virtual royal self of hitherto unimagined quality and intensity. They half-captured and half-invented a rich past, which progressed from ancient Rome through the line of Charlemagne to the glory of the house of Habsburg and culminated in Maximilian's own high presidency of the Christian brotherhood of warrior-kings."[15]

Additionally, as his legends have many spontaneous sources, the Gedechtnus projects themselves are just one of the many tributaries of the early modern Maximiliana stream. Today, according to Elaine C.Tennant, it is impossible to determine the degree modern attention and reception to Maximilian (what Tennant dubs "the Maximilian industry") are influenced by the self-advertising program the emperor set in motion 500 years ago.[16] According to historian Thomas Martin Lindsay, the scholars and artists in service of the emperor could not expect much financial rewards or prestigious offices, but just like the peasantry, they genuinely loved the emperor for his romanticism, amazing intellectual versatility and other qualities. Thus, he "lives in the folk-song of Germany like no other ruler does."[17] Maximilian Krüger remarks that, although the most known of all Habsburgs, and a ruler so markedly different from all who came before him and his contemporaries, Maximilian's reputation is fading outside of the scientific ivory tower, due to general problems within German education and a culture self-defined as post-heroic and post-national.[18]

Legends and anecdotes

[edit]

Maximilian is the subject of several legends and anecdotes, which themselves would later produce inspirations for artworks.

- The Faust legend: The legend is strongly based on a legend involving Maximilian, his first wife Mary of Burgundy and the humanist Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516), who was suspected by many to be a necromancer. Through his 1507 account, Trithemius was the first author who mentioned the historical Doctor Faustus. Being summoned to the emperor's court in 1506 and 1507, he also helped to "prove" Maximilian's Trojan origins. In the 1569 edition of his Tischreden, Martin Luther writes about a magician and necromancer (understood to be Trithemius) who summoned Alexander the Great and other ancient heroes, as well as the emperor's deceased wife Mary of Burgundy, to entertain Maximilian.[20] In his 1585 account, Augustin Lercheimer (1522–1603) writes that after Mary's death, Trithemius was summoned to console a devastated Maximilian. Trithemius conjured a shade of Mary, who looked exactly like her likeness when alive. Maximilian also recognized a birthmark on her neck, that only he knew about. He was distraughted by the experience though, and ordered Trithemius never to do it again. An anonymous account in 1587 modified the story into a less sympathetic version. The emperor became Charles V, who, despite knowing about the risk of black magic, ordered Faustus to raise Alexander and his wife from death. Charles saw that the woman had a birthmark, that he had heard about.[21] Later, the woman in the most well-known story became Helen of Troy.[22] The story of Maximilian, Mary of Burgundy and the Abbot "Johannes Trithem" later appeared as one of the Grimms' Tales.[23]

Another related story came from Hans Sachs' poem Dem Geschichte Keyser Maximiliani mit dem alchamisten (The story of Emperor Maximilian with the Alchemist), which in turn was based on an incident in the seventh century involving the alchemist Morienus and Sultan Khalif of Egypt. Hans Sachs's story allegedly inspired Goethe's scene at the imperial court in Faust II. The story is as the following: Maximilian is approached in his court in Wels by an alchemist who proposed to show him his art. Later, after the transformation had been completed, the alchemist disappeared, leaving a gold cake of ten measures and a message:

O keyser Maximilian,

Wellicher dise kunst kan,

Sicht dich nochs römisch reich nit an,

Daß es dir solt zu gnaden gahn.

O Emperor Maximilian,

Whoever masters this art

Cannot see, for you or the Roman empire,

That matters will turn out well.

Maximilian then learns that the alchemist was a Venetian and sent by his enemies. The next time the poet returns to Wels, Maximilian has died.[24]

The blooming of the Faustus myth was fuelled by the witch craze of the time.[25]

- There are legends that associate Maximilian with swans in Bruges, the city that had once opposed Maximilian's rule in the Low Countries and held him prisoner for nearly four months. The Belgian and Dutch version, possibly dating from the nineteenth century, recounts that after his liberation, Maximilian forced Bruges to maintain swans as a perpetual remembrance for Peter Lanchals, his counsellor and confidant, who was beheaded by Bruges.[26][27] The German version, appearing early in a 17th-century edition of the Theuerdank, recounts that Maximilian's faithful jester Kunz von der Rosen tried to save the king, but was attacked and driven away by swans.[28][29] Another legend related to this episode in Maximilian's life and Kunz von der Rosen is that, Kunz von der Rosen, under a priest's garb, tried to save the king by exchanging place with him, but Maximilian, either knowing that an army was coming to save him, fearing for von der Rosen's life or worrying about his dignity, refused.[30][31] Anton Petter (1791–1858) painted the scene of von der Rosen trying to free Maximilian in his 1826 work Kunz von der Rosen sucht den Kaiser Maximilian I. aus der Gefangenschaft zu befreien.[32]

- Brugse Zot ("Brugge Fool"): After Bruges's revolt had been subdued, Maximilian forbade the organization of fairs. To appease him, the city organized a conciliatory celebration with merrymakers and fools. When he came, they asked him to allow them to establish a madhouse ('zothuis'). He told them that as their city was full of fools, they could just close the gates of the city and they would have a madhouse already. Brugse Zot became the nickname for people of Bruges and also name of an iconic beer, brewed by the brewery De Halve Maan ("the Half Moon").[33][34]

There are two large murals (created in 2019) in the centre of Bruges, both related to the legend. One is Maria Van Bourgondië (by Jeremiah Persyn), in which Mary of Burgundy is depicted as a Jesus-like figure while Maximilian is in the guise of the Brugge Fool, riding a swan and holding a halfmoon. Another is De Dans der Zotten ("Dance of the fools") by Stan Slabbinck.[35][36][37]

- The Martinswand legend: According to this popular saga, the young Maximilian went to hunt chamois at Martinswand, a steep rock wall near Innsbruck, and found himself stuck for three days. A messenger of God or an angel, disguised as a young man in peasant's clothing, then appeared and led him to safely. According to Terjanian, parts this tale appeared during Maximilian's life, but the full version was first presented in the work Hercules Prodicius by the Dutch historian Stephanus Pighius (1520–1604), published in Antwerp in 1587.[38][39] The episode is depicted in Alfred Rethel's A Guardian Angel Rescuing Emperor Maximilian from the Martinswand (1836); Friedrich Krepp's Die Errettung Kaiser Maximilians I. aus der Martinswand (1849); Moritz von Schwind's Kaiser Maximilian I. in der Martinswand (circa 1860); Lorenz Clasen's Kaiser Maximilian I. in der Martinswand (1873); Ferdinand von Harrach's Kaiser Maximilian I. in der Martinswand (1867); Friedrich Hell (1869–1957)'s Kaiser Maximilian I in der Martinswand; Maximilian's Rettung in der Martinswand on the Fresco Innerkofler Street. In 1936, in the Kaiser-Maximilians-Grotte (Emperor Maximilian Cave, said to be created by Maximilian to commemorate the place he was stuck), a great cross and a statue of the emperor kneeling in front of it were erected by the sculptor Johannes Obleitner.[40] The popular ballad Zyps or Zirl is about this episode.[41]

Franz Schubert wrote the song Kaiser Maximilian auf der Martinswand, based on a text by Heinrich von Collin, about this legend.[42]

- Anecdote of Maximilian holding the ladder for Albrecht Dürer: Dürer was one of the most important artists in the service of Maximilian, whose court leaned towards egalitarianism. One day, Maximilian noticed that the ladder Dürer used was too short and unstable, thus told a noble to hold it for him. The noble refused, saying that it was beneath him to serve a non-noble. Maximilian then came to hold the ladder himself, and told the noble that he could make a noble out of a peasant any day, but he could not make an artist like Dürer out of a noble.[43][44][45] The story later became subject of various paintings by nineteenth century painters such as August Siegert (1820–1883), Wilhelm Koller (1829–1884), Peter von Cornelius (1783–1867).[46]

This story and the 1849 painting by August Siegert, shown above, have become relevant recently. This nineteenth-century painting shows Dürer painting a mural at St. Stephen's Cathedral, Vienna. Apparently, this reflects a seventeenth-century "artists' legend" about the previously mentioned encounter (in which the emperor held the ladder). In 2020, during restoration work, art connoisseurs discovered a piece of handwriting now attributed to Dürer, suggesting the Nuremberg master's participation in creating the Viennese murals. In the recent 2022 Dürer exhibition in Nurembeg (in which the drawing technique is also traced and connected to Dürer's other works), the identity of the commissioner is discussed. Now the painting of Siegert (and the legend associated with it) is used as evidence to suggest that this was Maximilian. Dürer is historically recorded to have entered the emperor's service in 1511, and the mural's date is calculated to be around 1505, but it is possible they have known and worked with each other earlier than 1511.[47][48][49]

- Erasmus knew several stories about Maximilian, probably from gossips. Erasmus was a member of Charles V's councils. Erasmus and Maximilian's relationship was quite complicated, as they differed on ideological ground, mainly regarding Maximilian's warlike policies (when Guelders invaded the Low Countries in 1517, Erasmus even falsely suspected Maximilian of being in cahoots with other princes to extort money from his subjects).[50][51][52] Elsewhere he mentions Maximilian's keenness in judging characters. A story in his Colloquies tells how a young nobleman collected fifty thousand florins in tax but returned only thirty to the emperor who took it without question. After being induced to force him to explain, the emperor summoned the young man. The young nobleman said he would need to learn such account making skills from the assembled councillors, who were good at that business, first. The emperor smiled and let him go. Such stories added to Maximilian's reputation as a reckless financial manager and his officials as being corrupted (which might have been true).[53][54][55]

- In the War of the Succession of Landshut, during the Siege of Kufstein (1504), Hans von Pienzenau fought against Maximilian and his Bavarian allies. Maximilian took the fortress after a fierce artillery attack, with display of some of his latest artillery innovations.[58] Von Pienzenau had swore loyalty to Maximilian before switching to the Palatinate side, allegedly after being bribed with 30,000 guilders. But the main reason Maximilian became angered was that during the siege, they had refused his offer of surrender and used brooms to sweep up damage caused by his cannons to taunt him. Eighteen including Pienzenau were beheaded before Erich von Braunschweig, a favoured commander, pleaded for the lives of the rest.[59][60][61] Maximilian had forbidden any pleading, but Erich had saved Maximilian's life at the Battle of Wenzenbach and was his godchild.[62][63] After the siege, Maximilian rebuilt Kufstein into a powerful fortress, that still stands today.[64] He added the white, eye-catching Kaiserturm (Imperial Tower), at which there is now a permanent exhibition about him.[65][66] Now there is also a Ritterfest (knights' festival) in Kufstein that celebrates the memories of both Maximilian and Pienzenau.[67]

The scene is depicted by Johannes Riepenhausen in his Herzog Erich der Ältere von Calenberg und Kaiser Maximilian vor der Veste Kufstein in Tirol (pen-and-ink drawing around 1836; the same artist recaptured the scene in an oil painting in 1837 with Herzog Erich von Braunschweig bittet unter eigener Gefahr den Kaiser Max um Gnade für die zu Kuffstein Verurteilten),[68] On the wall of the nearby Auracher Löchl (the oldest winehouse of Austria), there is a depiction of the "last knight" with his cannon, opposing Hans Pienzenau.[65][69]

Works produced during Maximilian's lifetime

[edit]Maximilian was a major patron of the Renaissance in the North as well as a creative force in his own right,[70][71][a][b] and as such admired and able to maintain a relationship with many important artists and scholars of his time, most notably the humanists who praised him as a second Apollo and Father of the Muses.[72] In the Low Countries, Maximilian was a divisive figure, sometimes represented as the saviour of the country and sometimes as an autocratic tyrant (both possibly historical truths). While his Burgundian supporters (beginning with Molinet) tended to identify him with the Saviour (either in the guise of an eagle or the only begotten Son), Maximilian and his German supporters, especially his closest humanist circle, usually identified himself with Apollo-Phoebus (or the Sun), Hercules, Saint George and some other saints. Hugh Trevor-Roper remarks that in comparison with princes in Italy and Flanders as well as his own descendants, he did not commission great religious pictures. His tastes focused on himself, his family, German and Roman ancient heroes, and certain saints that he considered to have a kinship to his house.[73]

Gedechtnus

[edit]

Gedechtnus (memorial) is a term used by the emperor to refer to his monumental projects that served to institutionalize and memorialize his image and that of his family. The core of these was his massive autographical (or semi-autographical) corpus, including Theuerdank, Freydal, Weisskunig, the Ehrenpforte (Triumphal Arch), genealogical projects, various triumphal celebrations, architectural projects like his Cenotaph in Innsbruck, musical works by leading composers of the day like Heinrich Isaac and Paul Hofhaimer.[74][75][76] Maria Golubeva judges these projects as glorification for posterity, rather than propaganda in the normal sense of the word.[77] Theuerdank and Weisskunig are considered "the last attempt to revive medieval chivalrous ideals."[78] For Theuerdank, Freydal and Weisskunig as well as his Latin autobiography, Maximilian dictated content of chapters, provided sketches, revised drafts and was generally the driving force of these projects himself, although dozens of artists were involved in the creative process. In the cases of the Triumphal Arch and the Triumphal Procession, with the help of Johannes Stabius, he provided the texts on iconography and close supervision.[79][80][81][82] He was the designer of his own Cenotaph.[83]

Watanabe-O'Kelly notes that the projects often made use of luxurious elements, which indicated that they were not intended for the mass.[84] Maximilian issued privileges to printers of such projects, but a number of these works, by their design, "invited reproduction, reuse, appropriation and imitation". Theuerdank (one of the few projects completed in the emperor's lifetime), in particular, quickly became free-for-all, public shareware after its first publication in 1517, pirated initially by printers in the Low Countries.[85]

The Triumphal Arch as well as other depictions of triumphal celebrations by the emperor as his artists have been called "the most elaborate imaginary procession designs."[89] According to Jasper Cornelis van Putten, the Triumphal Arch is the most influential genealogical woodcut, following which printed monumental genealogies became popular with European rulers until well into the eighteenth century.[90] It is also "the most celebrated hierographic monument".[91]

Other than the glorification aspect, the emperor, with the help of his artistic advisors, had a habit of inject dark allegories and his inner turmoil into the works.[74][92]

The genealogical projects and the invented histories that went with them tended to attract criticisms even from the contemporaries for being overboard (even though other rulers also made extraordinary claims about their families), including the famous mathematician and astronomer Johannes Stabius. After the origins of the Habsburg had been traced back to Noah, Kunz von der Rosen brought before the emperor a retired soldiers' harlot and a beggar, who petitioned him to support them because they were all descendants of Adam. The emperor laughed. Later, Charles V personally tried to eliminate Theodoric from his grandfather's tomb (which was in some respects also a genealogical work) but failed, while Ferdinand I successfully eliminated Caesar and Ottokar.[93][94]

For portraits, he preferred woodcuts as it was the cheapest medium. The iconic oil painting Portrait of Emperor Maximilian I by Albrecht Dürer was a rare case another medium was used instead.[92]

Architecture

[edit]

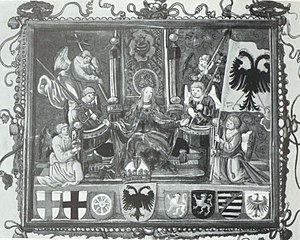

- The Wappenturm, or Heraldry Tower (now destroyed) in Innsbruck, was built in 1496 following the design of Jörg Kölderer and the Türing workshop that produced the Goldenes Dachl that stands next to it. It was built near the part of the palace in which arms and armour were stored. The tower serves as a billboard for dynastic propaganda, displaying the coats of arm of the territories (54 in total) Maximilian claimed. The standard bearers here had a more noble look in comparison with those on the Goldenes Dachl. The top showed the bust portraits of Maximilian and his two wives, as if on a royal balcony. Later, another royal couple was added, presumably Ferdinand I and Anna of Hungary and Bohemia.[95]

- A remarkable monument, that was never completed (as work ceased after Maximilian's death) is the Speyer monument to German emperors and empresses (the characters selected are Maximilian's ancestors, together with emperors from the Hohenstaufen and the Salic lines, who were buried at the Speyer Cathedral). The structure was intended to comprise a round temple on twelve octagonal pillars with the whole surmounted by a giant crown. Maximilian seemed to intend to create a bronze effigy of himself as the focal point of the structure.[96] The surviving crown is 6m is diameter, with a fragment in the shape of a palm-leaf being 1.55m high, and one of the eight surviving sculptures of emperors being 1.78m high. Like other Maximilianic monuments, the design is more Gothic than Renaissance.[97][98]

Another plan that was never carried out, partly for financial reason, was a memorial chapel for himself in Falkenstein (Falconstone[99]) near St. Wolfgang.[100] He was going to have himself buried in this area, until the Archbishop of Salzburg, Leonhard von Keutschach, persuaded him choose St. George's Cathedral, Wiener Neustadt, probably with considerable financial help.[101]

- Certain previously built structures were utilized and modified to befit Maximilian's propagandistic purposes. An extant example is the towers (Oberer Stadtturm and Unterer Stadtturm, also called Kaiser Maximilians Wappentürme or Maximilian's heraldry towers) in Vöcklabruck, which Maximilian realized to be easy to identify from distance. The facades were altered with frescoes that displayed coats of arms of the territories he ruled and those he aspired to rule as well, as well as an image of himself. During Napoleon's invasion, the frescoes were removed. After 150 years, during renovation, they were discovered and restored.[102]

- The Cour de Bailles was a square (now lost) in front of the Palace of the Dukes of Brabant that Maximilian and Margaret began to build in 1509. The angles were cut off with an open-worked stone balustrade, interrupted by pedestals (that carried the figures of birds and quadrupeds) and octagonal columns on each of which stood a duke of Brabant. The figures were designed by Jan van Roome, alias des Bruxelles, and the sculptor was Jan Borman, who executed them in wood, which would be cast in bronze by Renier van Thienen, who only completed the statues of Godfrey II, Godfrey the Bearded, Maximilian and Charles V. The construction would be completed in 1521 though.[103]

- In 1513, he finished the imposing and very costly tomb of Frederick III in St. Stephen's Cathedral, Vienna (the original design was from the Netherlander Nikolaus Gerhaert of Leiden; Maximilian and his circle played the decisive role in the appointment of the tomb and the décor). This is among "the fourteen burial sites of late-mediaeval kings and emperors of the Holy Roman Empire was never looted, disturbed or altered". There were rumours that the tomb was empty, so a very small opening was created in 1969 for the purpose of observation and recording, but only in 2013, it became possible to take photographs. There are gilt metal plates with inscribed texts that celebrate Frederick's and Maximilian's achievements.[104][105]

Astrology

[edit]

Inheriting an interest in astrology from his father, Maximilian extensively utilized astrological works for propaganda in general and for self-presenting in particular, although Darin Hayton notes that, propaganda here should not be understood as an attempt to deceive the public, as propaganda is sometimes described in the modern sense. Rather, Maximilian and his circles were sincere in their belief of a relationship between politics and science, and in their efforts to promote an enhanced role for scientific knowledge in politics.[106]

- In Johannes Lichtenberger's popular 1488 Pronosticatio, the main fight happens between a pair of eagles (Frederick III and Maximilian, by then King of the Romans) with a wolf (symbol of France; their kings are coded as lilies). The Bavarian Wittelbachs, also antagonistic, are coded as lions. As the author tries to collect as many prophesies as possible, the French are at times presented positive. Even a French version of the emperor-prophecy (Kaiserprophetie) with anti-Habsburg tone is mentioned, that a new "Karl" of French ancestry will rule Germany and reform the Church and his name begins with "P". The author also predicts a conflict between the Eagle and the Pope, as well as the conquest of Rome.[107][108]

- The Tractatus super Methodium, written by the Augsburg lawyer and cleric Wolfgang Aytinger, edited by Sebastian Brant and printed in 1498 by Michael Furter in Basel, also proved a best-seller, although less well-researched than Lichtenberger's work. Maximilian is shown fighting the Turks, now the main enemy, although it is concluded that the fight will ultimately be won by a king whose name begins with "P" (Philip the Handsome, whose mother comes from Francia) [109]

Plays

[edit]Dramatic works by Maximilian's court scholars and Poet Laureates as well as others who supported him tended to double as encomium for imperial politics and commentary on contemporary events.

- Jakob Locher's Tragedia de Turcis et Suldano and Historia de rege Frantie supported Maximilian's anti-Ottoman and anti-French agenda. The works predicted the defeat of the French and the Ottoman (even though the fighting had not started yet).[110] Historia de rege Frantie is the first German Neo-Latin tragedy, also the first German Humanist tragedy.[111][112]

- Konrad Celtis wrote for Maximilian Ludus Dianae and Rhapsodia de laudibus et victoria Maximiliani de Boemannis. The Ludus Dianae displays the symbiotic relationship between ruler and humanist, who are both portrayed as Apollonian or Phoebeian. Maximilian was the most important of Celtis's earthly Apollos, while Celtis, as one of the most important advisors of Maximilian, played an essential role in shaping the image of Maximilian.[113][114][115]

The other humanists support this image as well – the idea behind was that an ideal ruler outshone everything. The function of the emperor as the promoter of arts and learning (Musagetes or Musarum pater) was important but the political mission was highlighted as well (as shown by Willibald Pirckheimer's text that accompanied the Great Triumphal Carriage, mentioned above.) Apollo was also the symbol of the Renaissance that Celtis and the humanists wanted to bring to Germany.[116][117][118]

Poems

[edit]

- The character of Priest King Johannes or John as recorded in the Ambraser Heldenbuch (a compendium of medieval epic, partly inspired by the frescoes depicting ancient heroes Maximilian saw in the Runkelstein Castle[119]) commissioned by Maximilian and written by Hans Ried, according to Klaus Amann is an alter ego of Maximilian, who considered himself as a descendant of the race of Holy Grail (Gralsgeschlecht). The story of Loherangrin, son of Parzival and cousin of John, as recorded by Wolfram von Eschenbach's work, is also connected to Maximilian's life story, as Loherangrin was taken by a swan to Antwerp, where he married the Princess of Brabant. When asked by his wife where he had come from (something he had forbidden her to do), Loherangrin left, but their descendants remained. Many generations later, Maximilian married the Princess of Burgundy (Mary of Burgundy, who was also Duchess of Brabant).[120]

Rainer Schöffl connects the story of Kriemhild and Siegfried in the Nibelungenlied (also part of the Ambraser Heldenbuch) to Mary of Burgundy and Maximilian. Kriemhild, also a Burgundian princess, is often shown with a falcon. The "falcon dream" (Falkentraum) is a favourite motif the Nibelungenlied. In the first adventure, she dreamed of a tame falcon who was killed by two eagles. In the story, Siegfried set out for Worms (capital of the Kingdom of Burgundy according to the Nibelungenlied) because he heard of Kriemhild's beauty. Siegfried is depicted as a passionate hunter, too, with equipments similar to those used by Maximilian, as shown by his Geheimen Jagdbuch (Hunting Book). He is also a dragon slayer like Maximilian's favorite saint, Saint George. Schöffl notes, though, that the emperor must have realized that some of Siegfried's actions (like cheating Brunhild with a magical cloak to gain Kriemhild as a "bought bride") did not fit into his chivalrous concepts, and that was why he did not claim Siegfried as one of his ancestors. Like Maximilian and Mary's marriage, Siegfried and Kriemhild's marriage also became a love marriage, but ended too soon and suddenly, in a violent manner.[121] Gunda Lange writes that the Nibelungenlied and the Kudrun (both take the woman as the central character and are put next to each other in the Ambraser Heldenbuch) are connected by the overuse of the dangerous courtship motif, which seems to reflect Maximilian's literary preferences, as this is the way his courtship of Mary of Burgundy is stylized in his works.[122] Christopher Wood links the Ambraser Heldenbuch to extensive archaeological activities by Maximilian (already started by his father Frederick III around the city of Worms). The work seemed to be intended to double as materials for his genealogical projects.[123]

- The epic Austriados (around 1513) glorifies Maximilian's deeds in the War of Bavarian succession. The author was Riccardo Bartolini (born 1470), Maximilian's "most important Neo-Latin panegyrist".[125] This is one of the Latin epics dedicated to the emperor by Italian poets, including Encomiastica (1504) by Giovanni Stefano Emiliano Cimbriaco, Pronostichon de futuro imperio propagando (1493/1494) by Giovanni Michele Nagonio, Magnanimus (ca. 1517–1519) by Riccardo Sbruglio. Pulina notes that the epics aspire to connect to traditional ideals and models of heroization, but also adapt to the person of Maximilian and contemporary developments.[126]

- Sebastian Brandt was a lifelong admirer of the emperor and dedicated various panegyrical works to him,[127] although he criticized Maximilian on some aspects.

For example, he criticized the court historians who fawned over their prince in his The ship of fools:[128][129]

I wish I had a covered ship

Wherein all courtiers I would slip

And those who eat at nobles' board

And hobnob with a mighty lord

So that they may be undisturbed

And by the rabble never curbed.

- Helius Eobanus Hessus, widely reputed to be Germany's finest Latin poet and never crowned Poet Laureate, rebuked the emperor for rewarding undeserved poets, and expressed his pride that it was the Muse who gave him the laurel:[130]

Nubila scandentem lauri de stipite cygnum

Hesso stemma suum Iibera Musa dedit.

The generous Muse gave Hessus for his device the swan

rising from the laurel branch to the clouds.

- Ulrich von Hutten was in the service of the emperor for some time, and wrote poems dedicated to Maximilian.[131] One of this was Italia to Maximilian, to which Eobanus Hessus replied with Maximilian to Italia, using the emperor's name.[132]

- Jean Molinet's chef d'oevre "Ressource du petit peuple" (a work about the fates of "small people" in wars), described either as poem or rhythming prose,[133][134] addressed Maximilian, whose character he praised but whose politics he reproached.[135] Before Maximilian came to Burgundian lands, Molinet wrote Le naufrage de la Pucelle (1477), a work that mixed prose and poetry that advised Mary of Burgundy (presented in the work as the Pucelle) on how to deal with the death of her father and the threat from France (presented as whales and sea monsters). Maximilian was alluded to as an eagle that would save the ship.[136][137] When Molinet depicted them as pagan deities, like in Bergier sans Soulas (1485), Mary was portrayed as Lune (Moon, Diana) while Maximilian was Apollon, Phoebus, Titan or King of Ilion, Philip was Jupiter, Margaret of Austria was Venus, while the King of France was Pan and the King of England was Neptune.[138][139] In an updated version of his Complainte (the original was written in 1464), Maximilian was a lion and Mars.[140]

- In their 1507 Cosmographiae Introductio (a revolutionary work in cartography, together with the map Universalis Cosmographia that accompanies it), Martin Waldseemüller and Matthias Ringmann wrote in the dedication to Maximilian:

Since thy Majesty is sacred throughout the vast world

Maximilian Caesar, in the furthest lands,

Where Phoebus Apollo raises his golden head from eastern waves

And seeks the straits called by Hercules' name,

Where midday glows under his burning rays,

Where the Great Bear freezes the surface of Ocean ...

The poem is short but often noted for the connection between cosmography and imperial ideology.[141][142][143][144]

Drawings, paintings and engravings

[edit]- A pair of sketches (late fifteenth century or early sixteenth century at the latest) portray the King of the Romans, pale and emaciated after almost three months of imprisonment (although his captors tried to make his imprisonment pleasant with banquets and luxury), having a banquet and attending the Mass of Peace on his last day in Bruges. Warburg and Friedländer opine that the sketches likely reflect an immediate visual experience, because, among other reasons, from a retrospective point-of-view, an artist would not consider the banquet an important moment and no one would want to be reminded of the oath Maximilian was forced to take and later did not keep.[145][146]

During the 1482–1492 Flemish revolts against Maximilian as well as the later war against Guelders (which was believed, by many, as a dynastic struggle between the Habsburgs and the King of France, that had nothing to do with the Low Countries), as continual warfare and taxes (levied to support those wars) put pressure on the society – including the middle class that the contemporary renown painter belonged to, many works portraying Maximilian in a satyrical way appeared.[147][148]

The signs through which one can recognize the allusion to Maximilian and tend to be the features of his face, especially his distinctive nose, and the imperial eagle.[149]

- Hans Memling's St. Ursula Shrine, dated around 1488–89, showed the author as an opponent of Maximilian's politics.[150]

During the 1510s and 1520s, Maximilian's vassals and retainers tended to commission Holy Kinship paintings to praise the Habsburg's marriage politics and also to pray for the prosperity of their own family. Other examples include:

- In 1509, Lucas Cranach the Elder painted the famous Holy Kinship Altarpiece for Frederick and John, the brother Electors of Saxony. In this instance, as the brothers were territorial lords instead of Maximilian's direct vassals, the appearance of the emperor as Cleophas (left) seemed to have another purpose, related to political problems within their territory. Here Maximilian-Cleophas was the husband of Anne and not Mary Cleophas like in the Strigel diptych.[151][152][153]

- The famous diptych of Maximilian's extended family (after 1515), painted by Bernhard Strigel, labels Mary of Burgundy as "Mary Cleophas, believed to be sister of the Virgin Mary" while Maximilian was labeled as Cleophas, brother of Joseph.[154] This painting was likely commissioned to commemorate the 1516 double wedding (between House of Habsburg and House of Hungary) and then bequeathed to the scholar Johannes Cuspinian as a sign of imperial favour (it would become part of his family altar and some years later was paired with another Holy Kinship painting that depicted the family of Cuspinian).[155]

- Sebastian Scheel's 1517 altarpiece, in which the emperor also features as Cleophas.[151]

- Jan van Scorel's Holy Kinship Altarpiece, painted in 1520, in which St.Joseph, who wore a hat reminiscent of the style of the Order of the Golden Fleece and had a hawk nose, clearly resembled Maximilian.[151]

Saint George was the emperor's favourite saint. Maximilianic iconography tends to fuse the saint and the emperor, as the Defender of Christendom. The cult of Saint George nurtured by Maximilian caused ambitious rivals to emulate to compete with him (for example, Frederick the Wise of Saxony hired Lucas Cranach to make works depicting Saint George for him, that rivalled those made for the emperor).[156]

- In 1508, the year Maximilian became Emperor-elect, Hans Burgkmair executed double chiascuro woodcuts, featuring Saint Georgle and Maximilian, completed with an inscription describing him as "vanguard of the army of Christians".[157]

- Around 1509–1510, Daniel Hopfer created the etching The Emperor Maximilian as Saint George (dated by Madar to 1518/1520 and Silver to 1519).[158][159][160]

- Around 1515, Lucas Cranach produced the work Maximilian idealized as Saint George.[161]

On his deathbed, Maximilian planned a project called Arch of Devotion (Andacht), of which the title page would show "Maximilian, crowned and enthronedin the armor of the Order of St. George, whose shield hangs above him, balanced by the joint arms of Austria and Burgundy, alongside the central imperial arms above the throne". The emperor also ordered that: "Write [of] my Tomb institution and the Order of St. George as well as of my family and ordained descent." The plan was never carried out. Instead, his death was glorified by a woodcut by Hans Springinklee under the order of Johannes Stabius that described a complete different scheme (see below)[162] The idea was laid out in 1512. It is unclear whether this was meant as a counterpart for the Ehrenpforte or a program for the fresco cycle of the planned memorial chapel in Falkenstein. Müller opines that it is possible it was intended to serve both purposes.[citation needed]

Maximilian's veneration of Saint George also influenced the knights of his time, who shared his ideals of chivalry.

- Hans von Hungerstein (1460–1503) commissioned the Master of the Strasbourg Chronicle to illustrate his personal edition with a depiction of Maximilian as an ideal knight, with features of Saint George. The depiction also shows how von Hungerstein, as a knight himself, wanted to be remembered.[163]

- The knight Florian Waldauf, Maximilian's trusted companion who rose from a low status and was a significant patron and collector of artworks himself (several artworks commissioned by Waldauf depict Maximilian), modelled himself after the emperor in veneration of the saint.[164] The portrait of Waldauf by Marx Reichlich (1500–1505) In the altarpiece he commissioned from Marx Reichlich, Saint George and Saint Florian appeared behind a kneeling Waldauf. Art historians usually note that the one who is depicted in the form of Maximilian is Saint Florian, Waldauf's name saint though.[165][166][167]

During his reign, Maximilian and his humanists reinvented Germania as the mother of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation.[171][172] In the previous eras, she was presented as one of the lands conquered or ruled by the Roman emperors, and then by the Holy Roman Emperors (see also: History of the personified Germania), often in subordination to both imperial power and Italia (or Roma) and Gallia. In Maximilian's imagination, she reflected the self-image of emperor and took a central role in his Triumphal Procession (Maximilian died before this project was completed though. When it was first printed in 1526 by Archduke Ferdinand, the future emperor, she disappeared.) She was pacific, yet virile, and as the emperor personally dictated, with her hair loose and wearing a crown.[169][170][171][173][174] She was presented as Mother, Sovereign Lady (Herrscherin), the Empire and the Birthland, as well as embodiment of Imperial rulership.[175] The humanist Heinrich Bebel also spread a story about his dream, in which Germania told him to talk to her son (Maximilian).[176]

His first wife, Mary of Burgundy, played an important role in Maximilianic iconography, as display of personal attachment or representation of the fusion of the Houses of Burgundy and Austria or both.[177][178] In many cases, her iconography is blended with that of the Virgin Mary,[136][179][180][181] who was her patron, and also especially revered by the emperor (his other favourite saints tended to be military saints).[182]

Maximilian kept certain themes consistent in representations of the two Marys and his association with them for decades. According to Silver, when he supervised Mary of Burgundy's tomb in the Church of Our Lady in Bruges, Maximilian had already anticipated some later elements for his own burial. Their tombs were both made in bronze, and both of them were buried beneath the altar. Both tombs show attention to the assertive rather than the mournful side of family ancestry and possessions.[183]

- In the Hours of Mary of Burgundy (according to Anna Eörsi, Maximilian was the last commissioner of this book, likely from the time he became Mary's husband or a new father. Images were also added after Mary's death. Hugo van der Goes was likely the illustrator), (folio 14v), Maximilian appears as a deacon waving the censer and bowing down before the Virgin (image of Mary of Burgundy) and the Child (image of Philip the Fair), the new ruler of the world. The image is likely inspired by the legend of Augustus paying homage to the infant Jesus.[184]

- Eörsi notes that in 1477, a medal celebrating Mary and Maximilian's wedding (likely commissioned by Maximilian himself), displays the motif of the Virgin with Child as well, with an inscription using content from the Song of Songs ("tota pvlcra es amica mea et macvla non est in te": "you are wholly fair and there is no blemish in you") – the obverse shows names and coats-of-arms of the couple while the reverse show the Virgin between two saints.[185] Karaskova agrees that the one who commissioned this medal should be Maximilian but the date must have been much later (a sign is the symbol of the Order of the Golden Fleece, which he did not become a member – and its sovereign – until 1478).[186]

The appearance on the medal of Saint Sebastian, a saint to whom Maximilian especially devoted, seems to suggest the connection to his status as King of the Romans (he was elected in 1486). Also in this year, an image produced for the book usually called Maximilian's Old Prayers Book was created, showing Maximilian praying to Saint Sebastian. There are three falcons in the picture: the one chasing another bird seems to be an allegory for Maximilian himself, protecting mother and child (Mary and Philip).[187]

- In one of Albrecht Dürer's most famous works, the Feast of the Rosary, the Virgin Mary (representation of Mary of Burgundy, according to Klaas van der Heide) was depicted holding the infant Jesus (representation of Philip the Fair) while placing a rosary on the head of a kneeling Maximilian.[190]

Rothenberg notes that, in the painting (considered by him to be a "direct visual counterpart" to the motet Virgo prudentissima, mentioned below), "The most prudent Virgin thus crowns the Wise King with a rose garland at the very moment when she herself is about to be crowned Queen of Heaven."[191]

- In Dürer's 1518 Death of the Virgin, or the Dying Mary of Burgundy, which anticipated the emperor's death in 1519, Maximilian is shown as an apostle bowing down in distress (next to Zlatkonia, the commissioner of the painting, who is shown as reading an open book in the middle of the room; Philip the Fair is depicted as a young Saint John standing next to Mary) in front of the dying Virgin (or Mary of Burgundy). Her soul, depicted as an infant, is about to get crowned by Christ in Heaven. Anna Jameson remarks that, the painting "all the legendary and supernatural incidents with the most intense and homely reality". The Latin inscriptions are passages taken from the Canticles, or Song of Songs, about Mary, coming from the Desert, beautiful as the moon and excellent as the sun, terrible as an army, rising to be reunited with her beloved and crowned in Heaven. [c][192][193]

- The motif of the Virgin and the Eagle, as the shared iconography of Mary of Burgundy and Maximilian, was also seen during Maximilian's "joyous entry" into Antwerp (1478), on one of the tableaux presented to him by the city. An eagle (also alluded to as the presence of the Holy Spirit) was shown offering his own blood to the maiden. The symbol for both Antwerp and Burgundy was also a virgin, while the eagle was the symbol of the House of Habsburg. The Antwerp (later, his loyal ally in his later turbulent regency) community seemed to welcome Maximilian as their saviour, but also wanted to subtly remind him of limits to his powers and his responsibilities as ruler together with Mary.[179]

Music

[edit]

- The monumental motet Virgo Prudentissima, that describes the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, was commissioned by Maximilian and written by Heinrich Isaac in preparation of the 1508 coronation of the emperor and played a very important role in Maximilianic iconography. It affiliates the reigns of two sovereign monarches – the Virgin Mary of Heaven and Maximilian of the Holy Roman Empire. The motet describes the Assumption of the Virgin, in which Mary, described as the most prudent Virgin (allusion to Parable of the Ten Virgins), "beautiful as the moon", "excellent as the sun" and "glowing brightly as the dawn", was crowned as Queen of Heaven and united with Christ, her bridegroom and son, at the highest place in Heaven. Rothenberg notes that, "In Isaac's compositions Mary becomes the figurative mother who crowns Maximilian, just as King Solomon's mother had crowned him." Other than Dürer's Feast of the Rosary, Rothenberg opines that the idea of the motet is also reflected in the scene of the Assumption seen in the Berlin Book of hours of Mary of Burgundy and Maximilian. The antiphon of the motet reads:

Virgo prudentissima, quo

progrederis quasi aurora valde

rutilans? Filia Syon tota formosa

et suavis es, pulchra ut luna

electa ut sol.

Most prudent Virgin, where are you

going glowing brightly as the dawn?

Daughter of Zion, you are wholly fair

and sweet, beautiful as the moon,

excellent as the sun.

The motet's text by George Slatkonia, expanding on the antiphon, reads: "The most prudent Virgin, who brought holy joys to the world, and transcended all spheres, and melted the stars beneath her feet with brilliant beams and gleaming light [...] the Mother of the eternal almighty, the Queen, powerful in Heaven, on land and at sea, whose divinity is deservingly venerated [and whom] every spirit and human being adores? We call upon you, Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, to pour upon her ears chaste vows and prayers for the holy Empire, for the Emperor Maximilian; may the omnipotent Virgin grant that he conquer his malicious enemies; may he restore peace to the people and safety to the lands. [...] the highest place belongs to Him by whom you were assumed, to whom you shine beautiful as the moon and are as excellent as the sun."[196][197]

Later, around 1537–1538, Virgo prudentissima was rewritten by Hans Ott to be rededicated to Christ as Christus filius Dei (all Marian references were replaced) and Maximilian was replaced with his grandson Charles V, then the reigning emperor.[198]

Moritz Kelber agrees with Rothenberg's interpretation of Virgo Prudentissima and its connection to the Feast of the Rosary. He adds that Maximilian considered the Virgin the patron of his reign and symbol of his march to Italy. The Marian symbols appeared notable not only in regard to the Reichstag at Constance but other occasions like Philip the Fair's funeral.[199] Later, in the Reichstag of Augsburg (1548), his eldest granddaughter Mary of Hungary "appropriated" Marian symbols through music as well (in this case, the Virgin became associated with the ruler herself).[200]

The Virgin appears in other composers' works too, with some of the most notable being:

- Sub tuum presidium by Pierre de la Rue: The motet sets to music one of the popular Marian prayers ("under your protection and shield..."), which seemed to be particularly significant for Maximilian. In 1508, when he paid a splendid visit to Antwerp, he placed his activities under Her protection with this motet.[204]

- "Summe laudis o Maria" by Benedictus de Opitiis: The motet was produced and performed for the same occasion in 1508. The text, composed by Petrus de Opitiis (brother of Benedictus) begins with a praise for the Virgin which is followed by a praise for Maximilian. reminiscent of Virgo Prudentissima's structure. Lodes notes that the son of Mary in the text does not mean Jesus alone (the son's name is never mentioned), but also Maximilian himself (similar to Obrecht's Missa Salve diva parens, mentioned below).[201]

CMME's editor argues that the date of 1508 for these motets is not a certainty.[205]

These motets were later printed in the Unio pro conservation rei publice (by Jan de Gheet, Antwerp, dated 1515), "eldest printed edition of polyphonic music in the Netherlands. It celebrates the visits of emperor Maximilian of Austria and his successor Charles V to the city of Antwerpen in 1508 and 1515".[206][201]

- The Alamire manuscript VatS 160, a choir book sent to Pope Leo X as a gift and likely first made for Lord John III of Bergen of Zoom, presents Maximilian as the Saviour and the secular representative of God, and also contains numerous references to the connection between Mary of Burgundy and the Virgin Mary, based heavily on Molinet's literary "inventions".[207]

The texts Populus qui ambulat in tenebris vidit lucem magnam (1477) and Le paradis terrestre (1486) are both allegorical texts used as the titles of chapters in Molinet's Chroniques. In these texts, Emperor Frederick III is compared to God while Maximilian is seen as the Only Begotten Son, who is sent to save the Burgundian nation and wed Mary of Burgundy. The Le paradis terrestre describes Maximilian's return to the 'Kingdom of the Father', where he was crowned as king of the Romans.[207] The mass Missa Salve diva parens by the composer Jacob Obrecht (d.1505) declares: 'Hail divine mother of the lovely offspring, Virgin dedicated to the good things of eternity, through whom the true Light, God, shone upon the world, and the ruler of Olympus submitted himself to become flesh' ('Salve diva parens prolis amene, / eternis meritis virgo sacrata, / Qua lux vera, deus, fulsit in orbem / et carnem subiit rector olimphi'). According to van der Heide, here Mary (of Burgundy) and her Olympus (the Burgundian nation) is visited by the True Light (Maximilian). The mass was likely made to celebrate Maximilian's return to the Low Countries in 1508/1509.[208] The mass Missa Ave regina celorum, also by Jacob Obrecht, is a tribute to both the Virgin Mary and Mary of Burgundy. Here, Mary became the deceased heavenly Mother, Friend and Queen of Emperor Maximilian.[209]

Silver notes that Maximilian's vision of religious music was not the simple result of sacral precedents seen by him in the chapels of the Low Countries, but tied to his militancy, his self-image as a martial ruler and the strong right arm of the Christian faith. Alexander the Great and Caesar were great sources of inspiration for him in music, as he said himself in the Weisskunig.[210] Professor Nicole Schwindt notes that in his time, "this convergence of military heroism and artistic sensibility was a new profile for a ruler, which was not universally accepted and still had to be legitimized by citing Aristoteles." Beyond political representation, this reflects on Maximilian as an individual who turned to music for deeper aesthetic desires as well.[211]

- The song Innsbruck, ich muss dich lassen is usually associated with the memory of Maximilian, written by Isaac, although the legend that the emperor was the lyricist was now considered highly unlikely. The song can be found in early collections such as Liederbuch Ludwig Iselins (Ludwig Iselin's Songbook). The song Bentzenower (no.54) in this book is about the fight against Maximilian of Hans Pienzenau, the commander of Kufstein who was later executed after Maximilian took the fortress in 1504.[212]

- The ballad Fraulein von Britannia, appeared in 1491, tells the story of Maximilian and Anne of Brittany. Michael Mullet comments that the ballad is "royalist soft pornography", but portrays rulers as actual people.[213][214]

Armour and weapons

[edit]The ancient hero Hercules and the Biblical figure Samson were also favourite figures of the emperor and identified with him through different mediums of art. According to Silver, "Hercules, then, is a perfect pagan parallel to St. George or to the biblical lion slayer, Samson, illustrated later in the Prayerbook by Breu. Hercules and Samson also shared the parallel of being undone by women."[219]

- Frederick the Wise commissioned a suit of armour for Maximilian. The armour depicted images of Samson and Delilah, the Idolatry of Solomon, Judith with the head of Holofernes, and Phyllis and Aristotle. According to Jacqueline Q.Spackman, "The inclusion on male armor may have been a warning to the man wearing the armor that even the mightiest and most intelligent of men (in this case Emperor Maximilian) can be seduced or tricked by women."[220]

- There's a bard (now in the Royal Armoury in Madrid), usually identified as made by Kolman Helmschmied and originally belonging to Maximilian, before being inherited by Charles V. The figures of Hercules, here shown performing Labours of Hercules, is an allegory for Maximilian himself. Samson is shown with Delilah. The bard was once accompanied by a suit of armour that depicted the same subject.[221][222]

The extremely elaborated and innovative bards crafted by Lorenz Helmschmied were important as iconographic and propagandic devices for Maximilian in his Burgundian years, as the horse wearing his bards served as living banners for the master even when he could not be present himself. Maximilian utilized the technological expertise of Augsburg, renowned for its innovative wonders and automata, for his bards that, in combination with equine and human performances, would produce optical and technological marvels corresponding to the Burgundian entremets for the Burgundian viewers. Kirchhoff writes that, "In its most luxurious iterations, horse armor did far more than protect an expensive and extensively trained steed. It transformed the animal's body into a moving sculpture and a communicative surface upon which to inscribe the iconography of power. In the case of the bard now in Vienna, the crupper plates that encase the horse's flanks form imperial double eagles that are enlivened by etched feathers and emblazoned with an escutcheon bearing the arms of Austria. The corresponding crupper shown in images of the 1480 entries uses the marshalled heraldry of the Habsburg and Burgundian dynasties,supported by a figure that resembles the duchess herself, to declare the consolidation of Mary and Maximilian's power [...] No surviving equine armor approaches the technical and visual ambition of the articulated bard, and the Helmschmids are the only armorers known to have created matrixes of steel plates flexible enough to encase a horse's entire lower body as it moved. Indeed, this type of armor became associated with Maximilian, who continued to commission bards that covered horses’ legs and bellies to arm his own steeds and also as diplomatic gifts to forge alliances and demonstrate Habsburg power." The recipients of these bards included Sigismund I the Old, who was presented with "two coursers all covered with steel to the fetlocks and the belly, save in the spurring place".[223] Another case was Henry VIII's so-called Burgundian bard.[224]

- The bard shown on the 1517 Doppelguldine, like the armour Maximilian wore, displays the fluting technique associated with Maximilian armour.[217] It is known that there was connection between the development of the full bard Maximilian armour and the Landsknecht.[225][223]

Surviving examples of the parts of armour crafted specifically to cover the horse's legs are very rare. The most remarkable case is an element made for a horse's forearm or gaskin, decorated with the fluting technique and etched bands that display the style of Daniel Hopfer of Augsburg, the inventor of the metal etching technique (circa 1470—1536). This part is preserved in Brussels's Musée Royal de l’Armée et d’Histoire Militaire (10212). It is dated around 1515 and most likely made by the Helmschmid workshop.[217]

In Innsbruck, Maximilian inherited the legacy of Sigismund of Tyrol, who also loved high quality armour and had patronized armourers in the nearby Mühlau, who produced works that were sent as gifts by Sigismund to rulers in Hungary, Portugal, France, Scotland and Silesia.[231]

Insbruck's arms production was geared towards quality rather than quantity. The city could not compete with Augsburg and Nuremberg in mass producing war armour. [226][232] Other than Seusenhofer, another favourite master of Maximilian was Hans Laubermann, "the wealthiest armorer in Innsbruck".[231]

A particularly exotic invention of Seusenhofer was the pleated skirt armour, which required exceptional skill to deal with metal the same way as with fabric. According to the MET, "the base was an imitation in steel of the cloth skirt that was sometimes worn over armor. The deep, arched cutouts in front and back allowed the wearer to sit on horseback; the close-set holes along these openings were for the attachment of textile decoration, probably fringe. The etching imitates the elaborate embroidery and cut velvet of fashionable court costume." Works of this type contributed to Seusenhofer's status as Maximilian's favourite armourer for donations. A notable example was the harness made for Charles of Burgundy (future Charles V) in 1512-1514.[233][234][235]

The Maximilian armour style was likely originally conceived to "create a dazzling effect as sunlight reflected on its polished, rippling steel", although it turned out that the flutings strengthened the defensive capability of the armour. The flutings also might have been designed to imitate the pleatings of costumes in the late 15th century.[236]

Swords (see External links), knives, crossbows, cannons and other weapons were an artistic and propagandistic medium to Maximilian as well, although the audience here is more limited.[237][238]

- A blued steel ceremonial sword (Prunkschwert), made by Hans Sumersperger (1492–1498) in Tyrol in 1496, opulently decorated with heraldic symbols and selected personal saints (one side is Saint George; the other is the Virgin) "was designed to be read from the tip of its blade back to its hilt, thus oriented clearly toward the sovereign who extended it in a ritual-like dubbing". Lhotsky notes that the Mary side shows more prestigious symbols, associated with higher ranked territories (kingdoms and duchies). Silver connects the heraldry seen here to those of the Wappenturm.[239][240]

- The hunting sword (Hirschfänger), also with blued steel and made by Sumersperger in Tyrol, shows the Mother of God on one side, standing on a crescent moon and crushing the serpent. The other side shows Saint Sebastian (also a patron of Maximilian, as the saint of soldiers and archers) being tied to a trunk and pierced by arrows. There are carved mother-of-pearl figures of a saint on the handle, presumably Barbara or Catherine.[241][242]

- The round shield of Maximilian, now in Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, was made around 1505. The single-headed eagle indicates that the date of creation was before Maximilian's 1508 coronation, and the style of decoration was before Daniel Hopfer made the breakthrough that unified the "heterogeneous world of motifs of the earlier period in the spirit of the Renaissance." A recent restoration allows the shield's pictorial wealth, unparalleled for its time, to be observed. The text of the motet Ave mundi spes Maria (there are differences in comparison with the version seen in the Codex Mus. Ms. 3154 in the Bavarian State Library, Munich, usually called the Choir book of Nikolaus Leopold) frames the shield, with the sentence "Mattheo Gurcensi episcopo dedicatum" (referring to the powerful official Matthäus Lang, then Bishop of Gurk) appearing several times. This motel seems to have played an important role in the court culture. The decoration shows diverse scenes that do not have one heterogeneous theme: there are scenes that represent masculine virtues and activities (fencing scenes, wild man fighting against a bear, Saint George defeating the dragon unicorn fleeing a hunter and running towards the lap of a maiden etc.) contrasting with scenes representing male weakness and female dominance (Phyllis and Aristotle etc.), scenes of heroic poeatry and love narratives (Tristan, Lancelot etc), dancers, man being hanged upside down, etc The animals (chamois, deers, stags, dragons...etc) and certain decorative motifs like the elaborated candelabra seem to have developed from models seen in French-Burgundian and Netherlandish tapestries or Italian and German arts.[243]

- The Hungarian shield (1515, Innsbruck) combines the style of Albrecht Durer and the Danube school with 15th century influence.[244]

Maximilian's inventory books

[edit]Maximilian commissioned a series of inventory books that record important information about his arsenals. These books called Zeugbuch, serve the aesthetic purposes as well.[245] The Vienna manuscript is the most famous one. A Zeugbuch recently discovered in Munich, Cod. icon. 222, "contains extensive information on the armament kept at approximately 100 locations – from castles and towns to monasteries and fortified churches – within the historical Slovenian territories."[246]

Tapestries

[edit]- Legend of Notre Dame du Sablon (or Our Lady of the Zavel) tapestries, commissioned by Franz von Taxis (1459–1517), circa 1518, with design attributed to Bernaert van Orley, features the scene Franz von Taxis was bestowed the postal rights by Frederick III according to Maximilian's arrangement.[247]

Posthumous depictions in artworks and popular culture

[edit]After Maximilian's death, generations of Habsburg rulers looked up to him as a model for their patronage and continued his artistic legacy.[248][249] Hugh Trevor-Roper writes that, "By harnessing the arts, he surrounded his dynasty with a lustrous aura it had previously lacked. It was to this illusion that his successors looked for their inspiration. To them, he was not simply the second founder of the dynasty; he was the creator of its legend – one that transcended politics, nationality, even religion."[250]

In the eighteenth century, Maximilian transformed from a dynastic symbol representing the Habsburgs to a national symbol for Germany. The Weisskunig was rediscovered and got its first edition in 1775. Herder saw his era, which he shared with other heroic figures like Albrecht Dürer, Martin Luther and Paracelsus, as the great German era, the most important one since the Romans, and the source of European constitution. In the nineteenth century, his story was re-stylized as "key moments in the German-Austrian self-image". Under the influence of both Romanticism and Historicism, his image took on many new directions.[251][252]

Poems

[edit]- In 1519, after the emperor's death, the Swiss poet Ceporinus wrote On the good life and apotheosis of Emperor Maximilian I in commemoration of him.[253]

- Maximilian's daughter Margaret also wrote a poem in commemoration of her father after his death.[254]

- Threnodia, a 1519 in commemoration of Maximilian's death by Pierre Gilles, is the author's best known Latin poetry work.[255][256]

- In Sigmund von Birken's 1657 Ostländischen Lorbeerhäyn, a paean to the House of Austria, Maximilian, a "male Pallas", represents the "duality of the sword and the quill". Christina Posselt-Kuhli notes that the poet was influenced by the image promoted by Maximilian and collaborators in his projects, which was the manifestation of a successful strategy combining political self-representation with cultural values.[257]

- Austrian writer Caroline Pichler (1769–1843) wrote the poem Max I. und Maria von Burgund about Maximilian and Mary.[258][259]

- Alexander Fischer (1812 – 1843) wrote the ballade Kaiser Max und Albrecht Dürer in 1842.[260][261]

- Heinrich Döring (1789–1862) wrote a poem of the same name.[262]

- Conrad von Rappard wrote the poem "Kaiser Maximilian" about the duel of Maximilian and Claude de Vaudrey.[263]

- Eberhard im Bart by Carl Grüneisen (1802 – 1878) is a poem that recounts how Eberhard defended the dignity of Württemberg in a feast attended by Maximilian and other princes.[263]

- In 1830, Anastasius Grün (11 April 1806 – 12 September 1876) published the epic poem Der letzte ritter (The last knight), with which this epithet has become almost the second name of the emperor, which is now the only aspect many Germans know about him.[18][264][265]

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem The Belfry of Bruges mentions the wedding by proxy of Mary of Burgundy and Maximilian, and the end of his imprisonment in Bruges, when he was forced to swear not to take vengeance on the rebels: "I beheld proud Maximilian/Kneeling humbly on the ground". He is also mentioned in Nuremberg.[266][267][268]

Plays

[edit]

- Pedro Calderón de la Barca's 1649 play Austria's second glory drew upon the Martinswand legend and raised it to an allegory of personal trust in God. On that year, the actor Augustín Manuel de Castilla was released from debtors' prison in Segovia so that he could play the young Maximilian.[19]

- Goethe's 1773 Götz von Berlichingen presents Götz von Berlichingen as the true Last Knight, in the place of Maximilian, who was revered by Götz despite being unable to control his anarchical realm. Stepan Shevyryov praises Goethe's genius for daring to give Maximilian a minor role and elevating Götz to the center.[270][271]

- He was a character in Ludwig Rellstab's 1824 five-act Karl der Kühne. Other important characters include Charles the Bold (titular character), Archduke Siegmund, Mary of Burgundy.[272]

- In Johann Ludwig Deinhardstein's Hans Sachs (1827) (which seems to be the inspiration behind Richard Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg), Maximilian came to Nuremberg incognito and helped Hans Sachs, a talented minstrel of humble origins, to marry the woman he loved.[273]

- In 1835, Anton Pannasch wrote the dramatic poem Maximilian in Flandern, describing events from the death of Mary of Burgundy to the revolt of Flander (including the imprisonment of Maximilian in Bruges). Other characters include Kunz von der Rosen, Cuspianian, Paul von Liechtenstein, Georg von Frundsberg, Philip the Fair and Margaret.[274]

- Gustav Freytag's 1844 play Die Brautfahrt oder Kunz von den Rosen (The bridal procession, or Kunz von den Rosen) is a comedy about Emperor Maximilian, which won the author the Berlin Court Theater Prize.

- Richard von Kralik's 1913 Der letzte Ritter (The last Knight), originally named Maximilian, is a play about the young Maximilian and seems to be a response to Goethe's Götz von Berlichingen.[275]

- Maximilian – ein wahrer Ritter is a 2019 musical written by Florian and Irene Scherz about Maximilian and Mary of Burgundy.[276][277]

- In the 2019 musical Schattenkaiserin, which is about the tragical life of Empress Bianca Maria Sforza, Maximilian is portrayed as a cold, adulterous husband who married Bianca for money and then abandoned her to focus on wars, other lovers and extravagant pursuits.The authors are Jürgen Tauber und Oliver Ostermann. The musical received three nominations for the German Musical Theatre Prize 2020/21 (due to the coronavirus crisis, the price covers both the 2019/2020 and 2020/2021 seasons) for composition, stage design and costume and won the prize for stage design.[278][279]

Fight books

[edit]

- The Thun-Hohenstein Album (Thun’sche Skizzenbuch) is a collection of 112 drawings created from the 1470s to about 1590 (with the majority produced in Augsburg in the 1540s) and rediscovered by Pierre Terjanian in 2011. The images display armoured figures in combat and at rest. It continues Maximilian's culture of remembrance and shows his successor Charles V as heir of a potent martial lineage.[280]

- The Tournament Book of Maximilian I (Turnierbuch Maximilians I.) is a tournament book created in the early 17th century and still not researched in depth. While the book depicts the emperor twice, the content is about the tournaments in Maximilian's time, rather than Maximilian directly. The second part is an armour book.[281]

Novels and other prose works

[edit]- In one of the imaginary dialogues written by the satirist Trajano Boccalini (1556 – 16 November 1613), Maximilian explained his opinions about Islam to the God Apollo, who chaired the debate. According to Maximilian, the introduction of Islam was a matter of policy and Mohammad was more of a politician than a sacred man. Apollo decided that Maximilian's opinions were entirely correct.[282][283]

- Cinthio's Hecatommithi (1565) is the chief source for Shakespeare's Measure for measure. Maximilian corresponds to Duke Vincentio and the story happens in Innsbruck (Innsbruck functioned as imperial capital city under Maximilian I), instead of Vienna.[284]

- Maximilian is an important character in the 1866 novel The Dove in the Eagle's Nest by Charlotte Mary Yonge.[285][286]

- In 1858, F.C.Schall published the historical novel Kaiser Maximilian der Erste in Wels und die Polheimer: Historischer Roman.[287]

- The Kaiser's tree by Wilhelmine von Hillern (1836–1916) is about the story of Hans Liefrink (Hans Liefrinck is a well-known block cutter) and Mailie, who met Maximilian once when they were young and planting a tree. Hans talked about his dream of becoming a wood carver like Dürer and marrying Mailie.[288]

- Hieronymus Rides: Episodes in the Life of a Knight and Jester at the Court of Maximilian, King of the Romans is a 1912 novel, written by Anna Coleman Ladd. The story is about Hieronymus, a jester and knight, who served his half-brother Maximilian loyally and undertook many adventures.[289][290]

- Maximilian is the central character of Peter Prange's 2014 novel Ich, Maximilian, Kaiser der Welt.[291]

- Des Kaisers Narr ist in Gefahr: Meine Reise in die Zeit von Kaiser Maximilian I. is a 2018 children fiction, written by Verena Wolf and Sonja Ortner and illustrated Christian Opperer. The story is about two children who time-travel with a court jester to Maximilian's era.[292]

- In the 2019 novel Die Luftvergolderin. Ein historischer Roman by Jeannine Meighörner, twelve-year-old Anne of Bohemia and Hungary married Maximilian (then aged 56) and became a widow, before finding true love with his grandson Ferdinand.[293]

- Der letzte Ritter von Füssen (2019) is the Vol.41 of the children's detective fiction series Die Zeitdetektive by Fabian Lenk.[294]

- The Eagle and the Songbird is a 2020 novel written by the music director Sara Schneider about the last years of Maximilian's reign, featuring the intertwining stories of the singer Catherine of Croy (the Songbird), the composer Ludwig Senfl and Maximilian (the Eagle).[295]

- Der Kaiser - Maximilian I. (2022) is a graphic novel by the Italian artist Giulio Camagni. The story takes place in the era of Maximilian, the Last knight. The characters also include Lena, a girl from a Tyrolean family; Sepp, a servant who joined the mercenaries to escape poverty; Queen Bianca Maria Sforza; a young Albrecht Dürer, who was on his way to Italy; the humanist Willibald Pirckheimer; Duke Ludovico Sforza; tha banker Jakob Fugger; the reformer Martin Luther. Andreas Kanatschnig of the Kleine Zeitung praises the novel's realistic and demystifying approach towards the figure of the emperor.[296][297]

- Loved by the Last Knight is a 2024 novel about Maximilian and Mary of Burgundy by Lily Harlem.[298]

Music

[edit]- The anonymous Proch dolor in Brussels 228 is a motet of mourning for the death of Maximilian (1519). There are debates regarding whether the composer was Josquin des Prez or someone else.[299][300][301]

- Hans Sachs (1494–1576), the meistersinger of Nuremberg, also called cobbler-poet, also often mentioned tales about Maximilian in his works. He was one of the source for the necromancer myth mentioned above.[302][303]

- Albert Lortzing's opera Hans Sachs (1840), with libretto by the composer, Philipp Reger and Philipp Jakob Düringer is based on Deinhardstein's play mentioned above: Hans Sachs competes at a song competition judged by Maximilian and wins the hand of Kunigunde, whom he loves.[304]

- Maximilian is a character in the 1849 five-act opera Ulrich von Hutten by Alexander Fesca, that featuring Hutten (who came to support Martin Luther, Maximilian, Franz von Sickingen in a 1523 setting.[305]

- Hutten und Sickingen is an 1889 dramatisches Festspiel (dramatic festival play) by August Bungert, composed to celebrate the 400th year of the bird of Hutten. The characters include Hutten, Sickingen, Maximilian, Albrecht Dürer, Konrad Peutinger and his wife Constanze, Jakob Spiegel.[306]

- Ignaz Brüll's opera Der Landfriede (1877) follows a comedy of the same name by Eduard von Bauernfeld (1869), which is about Maximilian and the world around him, set in Augsburg in 1518.[304][307]

- Theuerdank is an 1897 opera by Ludwig Thuille with libretto by Alexander Ritter. The work talks about the love of Theuerdank for Editha. The work was unsuccessful.[308]

- The 2019 album The last knight by the symphonic metal band Serenity is inspired by the life of Maximilian.[309]

Paintings, illustrations and engravings

[edit]

- In 1519, after the emperor's death, Johannes Stabius ordered Hans Springinklee to create a woodcut that described the emperor, kneeling in full regalia before God the Father, presented by his patron saints already featured in his Prayerbook (the Virgin with the Child, St. George, St. Andrew, St. Sebastian, St. Maximilian, St. Barbara, and St. Leopold), now acting as his intercessors. Silver describes this as an imagined apotheosis. The emperor mirrored God as His vicar, saying, "Moreover, you O Lord are my supporter: You are my glory and you glorify my reign." Stabius's verses extolled Maximilian's reign: "Germani gloria regni". The emperor was to be "united with Christ, with man, with God", and in turn evoked as a saint.[162]

- The copper plate portrait Emperor Maximilian I by Lucas van Leyden was the "earliest dated example of etching on copper." The softer copper allowed the artist to produce finer details. The artist utilized an innovative approach of combining etching with engraving, seen here for the first time in Northern Europe.[310][311][312]

- Charles V's depictions of his lineage often focuses on his paternal ancestors, especially Maximilian and Mary as progenitors of his house.[313] There is a pair of coloured drawings (on vellum), now kept at the British Museum, depicting Maximilian and Charles with their mottos, created by Jörg Breu the Younger (circa 1510 – 1547). The falcate wheel might represent life, Fortune, or perhaps the wheels used to punish prideful people seen in the Visions of Lazarus in the manuscript Livre de prières de Philippe le Bon, duc de Bourgogne, which belonged to Philip the Good. The globe on top is the globus cruciger, representing highest authority. Sagrario López Poza notes that this device of Maximilian, his most famous one, tended to go with the motto Per tot discrimina ("through so many moments of danger" – words from the Aeneid (I, 204), referencing the part Aeneas urged his companions to regain spirit after facing a storm in the seas of Sicily, caused by Juno's wrath. Halt Mass (keep the middle, be measured) was the motto Maximilian adopted as sovereign of the Order of the Golden Fleece.[314] The pomegranate is the emperor's personal symbol, according to Johannes Stabius: "although a pomegranate's exterior is neither very beautiful nor endowed with a pleasant scent, it is sweet on the inside and is filled with a great many well-shaped seeds. Likewise the Emperor is endowed with many hidden qualities which became more and more apparent each day and continue to bear fruit."[315]

- Around 1567–1571, Giorgio Vasari created the large-scale painting L'imperatore Massimiliano toglie l'assedio a Livorno (Maximilian lifting the siege of Livorno).[316][317]

- The engraving made by Dominicus Custos in 1600 likely was the basis for Cornelis de Vos and Rubens's 1635 portrait later.[318]

- Later Habsburgs continued with the triumphal iconography created by Maximilian and his artists. The Arch of Philip IV, "the widest and most splendid of them all", was created by Peter Paul Rubens, Jacob Jordaens and Cornelis de Vos (after 1614). The arch pays tribute to the founding moment of the marriage between Maximilian and Mary of Burgundy, a scene that had been depicted by Dürer in his Small Triumphal Chariot.[319][320] See also Mary of Burgundy in arts and popular culture.

- In 1635, Cornelis de Vos painted Portrait of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, which was retouched by Rubens.[321]

- The scene he bestowed his imperial crown on Amsterdam is depicted in several paintings and etchings, among them Keizer Maximiliaan I van Habsburg verleent de keizerskroon aan Amsterdam, Pieter Nolpe, after Nicolaes Moeyaert (1638),[322] or the anonymous Keizer Maximiliaan verleent de stad Amsterdam het recht de keizerskroon in haar wapen te voeren.[323]