Caesium iodide

CsI crystal

| |

Scintillating CsI crystal

| |

Crystal structure

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Caesium iodide

| |

| Other names

Cesium iodide

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.223 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| CsI | |

| Molar mass | 259.809 g/mol[2] |

| Appearance | white crystalline solid |

| Density | 4.51 g/cm3[2] |

| Melting point | 632 °C (1,170 °F; 905 K)[2] |

| Boiling point | 1,280 °C (2,340 °F; 1,550 K)[2] |

| 848 g/L (25 °C)[2] | |

| -82.6·10−6 cm3/mol[3] | |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.9790 (0.3 µm) 1.7873 (0.59 µm) 1.7694 (0.75 µm) 1.7576 (1 µm) 1.7428 (5 µm) 1.7280 (20 µm)[4] |

| Structure | |

| CsCl, cP2 | |

| Pm3m, No. 221[5] | |

a = 0.4503 nm

| |

Lattice volume (V)

|

0.0913 nm3 |

Formula units (Z)

|

1 |

| Cubic (Cs+) Cubic (I−) | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C)

|

52.8 J/mol·K[6] |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

123.1 J/mol·K[6] |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−346.6 kJ/mol[6] |

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵)

|

-340.6 kJ/mol[6] |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H315, H317, H319, H335 | |

| P201, P202, P261, P264, P270, P271, P272, P273, P280, P281, P301+P312, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P308+P313, P312, P321, P330, P332+P313, P333+P313, P337+P313, P362, P363, P391, P403+P233, P405, P501 | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

2386 mg/kg (oral, rat)[1] |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Caesium fluoride Caesium chloride Caesium bromide Caesium astatide |

Other cations

|

Lithium iodide Sodium iodide Potassium iodide Rubidium iodide Francium iodide |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Caesium iodide or cesium iodide (chemical formula CsI) is the ionic compound of caesium and iodine. It is often used as the input phosphor of an X-ray image intensifier tube found in fluoroscopy equipment. Caesium iodide photocathodes are highly efficient at extreme ultraviolet wavelengths.[7]

Synthesis and structure

[edit]

Bulk caesium iodide crystals have the cubic CsCl crystal structure, but the structure type of nanometer-thin CsI films depends on the substrate material – it is CsCl for mica and NaCl for LiF, NaBr and NaCl substrates.[9]

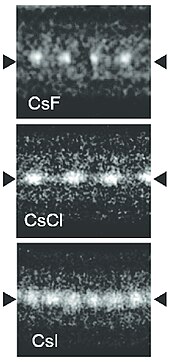

Caesium iodide atomic chains can be grown inside double-wall carbon nanotubes. In such chains I atoms appear brighter than Cs atoms in electron micrographs despite having a smaller mass. This difference was explained by the charge difference between Cs atoms (positive), inner nanotube walls (negative) and I atoms (negative). As a result, Cs atoms are attracted to the walls and vibrate more strongly than I atoms, which are pushed toward the nanotube axis.[8]

Properties

[edit]| Т (°C) | 0 | 10 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S (wt%) | 30.9 | 37.2 | 43.2 | 45.9 | 48.6 | 53.3 | 57.3 | 60.7 | 63.6 | 65.9 | 67.7 | 69.2 |

Applications

[edit]An important application of caesium iodide crystals, which are scintillators, is electromagnetic calorimetry in experimental particle physics. Pure CsI is a fast and dense scintillating material with relatively low light yield that increases significantly with cooling,[11] and a fairly small Molière radius is 3.5 cm. It exhibits two main emission components: one in the near ultraviolet region at the wavelength of 310 nm and one at 460 nm. The drawbacks of CsI are a high temperature gradient and a slight hygroscopicity.

Caesium iodide is used as a beamsplitter in Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometers. It has a wider transmission range than the more common potassium bromide beamsplitters, working range into the far infrared. However, optical-quality CsI crystals are very soft and hard to cleave or polish. They should also be coated (typically with germanium) and stored in a desiccator, to minimize interaction with atmospheric water vapors.[12]

In addition to image intensifier input phosphors, caesium iodide is often also used in medicine as the scintillating material in flat panel x-ray detectors.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Cesium iodide. U.S. National Library of Medicine

- ^ a b c d e Haynes, p. 4.57

- ^ Haynes, p. 4.132

- ^ Haynes, p. 10.240

- ^ Huang, Tzuen-Luh; Ruoff, Arthur L. (1984). "Equation of state and high-pressure phase transition of CsI". Physical Review B. 29 (2): 1112. Bibcode:1984PhRvB..29.1112H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.29.1112.

- ^ a b c d Haynes, p. 5.10

- ^ Kowalski, M. P.; Fritz, G. G.; Cruddace, R. G.; Unzicker, A. E.; Swanson, N. (1986). "Quantum efficiency of cesium iodide photocathodes at soft x-ray and extreme ultraviolet wavelengths". Applied Optics. 25 (14): 2440. Bibcode:1986ApOpt..25.2440K. doi:10.1364/AO.25.002440. PMID 18231513.

- ^ a b Senga, Ryosuke; Komsa, Hannu-Pekka; Liu, Zheng; Hirose-Takai, Kaori; Krasheninnikov, Arkady V.; Suenaga, Kazu (2014). "Atomic structure and dynamic behaviour of truly one-dimensional ionic chains inside carbon nanotubes". Nature Materials. 13 (11): 1050–4. Bibcode:2014NatMa..13.1050S. doi:10.1038/nmat4069. PMID 25218060.

- ^ Schulz, L. G. (1951). "Polymorphism of cesium and thallium halides". Acta Crystallographica. 4 (6): 487–489. Bibcode:1951AcCry...4..487S. doi:10.1107/S0365110X51001641.

- ^ Haynes, p. 5.191

- ^ Mikhailik, V.; Kapustyanyk, V.; Tsybulskyi, V.; Rudyk, V.; Kraus, H. (2015). "Luminescence and scintillation properties of CsI: A potential cryogenic scintillator". Physica Status Solidi B. 252 (4): 804–810. arXiv:1411.6246. Bibcode:2015PSSBR.252..804M. doi:10.1002/pssb.201451464. S2CID 118668972.

- ^ Sun, Da-Wen (2009). Infrared Spectroscopy for Food Quality Analysis and Control. Academic Press. pp. 158–. ISBN 978-0-08-092087-0.

- ^ Lança, Luís; Silva, Augusto (2012). "Digital Radiography Detectors: A Technical Overview" (PDF). Digital Imaging Systems for Plain Radiography. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-5067-2_2. hdl:10400.21/1932. ISBN 978-1-4614-5066-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-01-28. Retrieved 2017-08-28.

Cited sources

[edit]- Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 1-4398-5511-0.