The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway

| The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 22 November 1974[1][2] | |||

| Recorded | August–October 1974 | |||

| Studio | Island Studios Mobile at Glaspant Manor, Capel Iwan, Carmarthenshire, Wales | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 94:17 | |||

| Label | Charisma, Atco | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| Genesis chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway | ||||

| ||||

The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway is the sixth studio album by the English progressive rock band Genesis. It was released as a double album on 22 November 1974[1] by Charisma Records and is their last to feature the lead vocalist Peter Gabriel. It reached No. 10 on the UK Albums Chart and No. 41 on the USBillboard 200.

After deciding to produce a concept album with a story devised by Gabriel about Rael, a Puerto Rican youth from New York City who is taken on a journey of self-discovery, Genesis worked on new material at Headley Grange for three months. The album was marked by increased tensions within the band as Gabriel, who insisted on writing all of the lyrics, temporarily left to work with filmmaker William Friedkin and needed time to be with his family. Most of the songs were developed by the rest of the band through jam sessions and were put down at Glaspant Manor in Wales using a mobile studio.

The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway echoed the format of Genesis's debut album From Genesis to Revelation: a concept album with Christian themes which interweaves concise pop tunes centered around Gabriel's vocals and brief instrumental interludes, with most of the intrumental pieces not being acknowledged in the track list. The music and lyrics also make references to Genesis's early works and early influences.

The album received mixed reviews at first, and was the first Genesis album which failed to outsell its predecessors, but gained acclaim in subsequent years and has a cult following. "Counting Out Time" and "The Carpet Crawlers" were released as singles in the UK in 1974 and 1975; both failed to chart. A single of "The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway" was released in the US. Genesis promoted the album with their 1974–75 tour across North America and Europe, playing the album in its entirety. The album reached Gold certification in the UK and the US. The album was remastered in 1994 and 2007, the latter as part of the Genesis 1970–1975 box set which contains a 5.1 surround sound mix and bonus material.

Background

[edit]In May 1974, the Genesis line-up of frontman and singer Peter Gabriel, keyboardist Tony Banks, bassist and guitarist Mike Rutherford, drummer Phil Collins and guitarist Steve Hackett finished their 1973–1974 tour of Europe and North America to support their fifth studio album, Selling England by the Pound (1973). That album was a critical and commercial success for the group, earning them their highest-charting release in the United Kingdom and the United States. That June they booked three months at Headley Grange, a large former workhouse in Headley, East Hampshire, in order to write and rehearse new material for their next studio album.[4][5] The building had been left in a very poor state by the previous band to use it, with excrement on the floor and rat infestations.[6][7] By this time the personal lives of some members had begun to affect the mood in the band, causing complications for their work. Hackett explained: "Everybody had their own agenda. Some of us were married, some of us had children, some of us were getting divorced, and we were still trying to get it together in the country".[6]

Production

[edit]Writing

[edit]The band decided to produce a double album before they had agreed on its contents or direction, for the extended format presented the opportunity for them to put down more of their musical ideas.[8] A single album of songs telling segments of a story did not appeal to them,[9] and Banks thought they had gained a strong enough following by this point to put out two albums' worth of material that their fans would be willing to listen to.[10] They had wanted to produce a concept album that told a story for some time, and Rutherford pitched an idea based on the fantasy novel The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, but Gabriel considered it "too twee" and believed "prancing around in fairyland was rapidly becoming obsolete".[11][12]

Gabriel presented a surreal story about a Puerto Rican youth named Rael who is taken on a spiritual journey of self-discovery and identity as he encounters bizarre incidents and characters.[13][14] He first thought of the story while touring North America in the previous year, and pitched a synopsis to the group until they agreed to go ahead with it.[9][15] It was more detailed and obscure in its initial form until Gabriel refined it and made Rael the central character.[16] Gabriel chose the name Rael as it was one without a particular ethnic origin, but he later realised The Who used the same name on The Who Sell Out (1967); this annoyed him at first, but he stuck to the choice.[17] The band also found that "Ra" was common in male names in various nationalities.[18] Gabriel was inspired by a variety of sources for the story including West Side Story, "a kind of punk" twist to the Christian allegory The Pilgrim's Progress, the works of Swiss psychologist Carl Jung, and the surreal Western film El Topo (1971) by Alejandro Jodorowsky.[19] In contrast to Selling England by the Pound, which contained strong English themes, Gabriel made a conscious effort to avoid repetition and instead portray American imagery in his lyrics.[12] He had the story begin on Broadway in New York City, and makes references to Caryl Chessman, Lenny Bruce, Groucho Marx, Marshall McLuhan, Howard Hughes, Evel Knievel and the Ku Klux Klan.[20] Gabriel expressed some concern over the album's title shortly after its release, but clarified that the lamb itself is purely symbolic and a catalyst for the peculiar events that occur.[15]

During the writing sessions at Headley Grange, Gabriel insisted that having devised the concept he should write the lyrics, leaving the majority of the music in the charge of his bandmates.[21] This was a departure from the band's usual method of songwriting, as lyrical contributions on previous albums had always been divided among the members.[22] Gabriel explained that "I maintained then (and still do) that not many stories are written by committee", while Banks said that the rest of the group "felt it would give the album a bit of a one-dimensional quality and, for me, lyrically speaking, that is what happened."[23] This situation left Gabriel often secluded in one room writing the lyrics, and the remaining four rehearsing in another, since Gabriel could not write lyrics as fast as the others could write music, and so had to catch up on writing lyrics for music that had already been composed.[24][25] Gabriel ultimately fell so far behind that he relented and agreed to allow Rutherford and Banks to write the words for one song, "The Light Dies Down on Broadway".[26] Banks and Hackett suggested lyrics they thought would fit "The Lamia" and "Here Comes the Supernatural Anaesthetist" respectively, which Gabriel rebuffed.[27]

Further disagreements arose during the writing period when Gabriel left the group for a short period having accepted an invitation from film producer William Friedkin to collaborate on a screenplay, after he took a liking to Gabriel's surreal story printed on the sleeve of Genesis Live (1973).[14] Gabriel believed that he could collaborate with Friedkin as a side project. However, the other members maintained that this was an encroachment on the band's time and that Gabriel had to choose between them and Friedkin; he chose Friedkin.[28] In Gabriel's absence Collins suggested having the new studio album be purely instrumental, but the idea was rejected by the rest of the group.[29] Friedkin, however, was not prepared to split the band over a mere idea and Gabriel resumed work on the album.[30] Banks said he believes Charisma Records president Tony Stratton Smith had a key role in negotiating Gabriel's return to Genesis.[28]

Recording

[edit]After their allocated time at Headley Grange came to an end, Genesis relocated to Glaspant Manor in Capel Iwan, Carmarthenshire, Wales to record the album.[31] The remote location required them to use the mobile studio owned by Island Studios that was parked outside.[32][33] The Island mobile featured two 3M 24-track recorders, a Helios Electronics 30-input mixing console, Altec monitors, and two A62 Studer tape machines for mastering.[34] The album is the band's last with John Burns as co-producer, who had assumed the role since Genesis Live, recorded the previous year. Engineering duties were carried out by David Hutchins.[33] Burns and Gabriel experimented with different vocal effects by recording takes in a bathroom and in a cowshed two miles away.[34] Rutherford thought the album's sound was an improvement to past Genesis albums since it was not recorded in a professional studio, which benefited the sound of Collins' drums.[35] Collins compared the sound of the album to that of Neil Young's recordings made in his barn, "not studio, not soundproof, but a woody quality".[36] Gabriel said one track was recorded directly onto a cassette which was used on the album.[18]

Gabriel spent additional time in London after his wife, Jill underwent the difficult birth of their first child on 26 July 1974, leaving Gabriel often travelling back and forth.[27][37] Gabriel recounted, "the band were recording but instead of being somewhere reasonably close to where we were, in St Mary's Hospital, Paddington, they were out in Wales, so I was making these long pilgrimages. I was based in London and whenever things looked better I'd try and zoom back to Wales for the recording. This is something I think that the band would accept now, but back then they weren't very understanding. And I just lost it in a lot of ways because this was a life and death situation and so obviously much more important than an album or anything else."[38] Rutherford later admitted that he and Banks were "horribly unsupportive" of Gabriel during this time, and Gabriel saw this as the beginning of his eventual departure from Genesis.[39][40]

The backing tracks were put down in roughly two weeks.[27] Gabriel was still working on the lyrics a month later, and asked the band to produce additional music for "The Carpet Crawlers" and "The Grand Parade of Lifeless Packaging" so he could fit in words that had no designated section for them.[34] Thinking the extra material was to be instrumental, the band later found that Gabriel had sung over their new parts,[41] something that he also had done on Foxtrot and Selling England by the Pound and caused songs to be musically dense. Gabriel recorded his remaining vocals at Island's main studio in Notting Hill, London, where the album was mixed over a series of shifts as they were pressured to finish the album in time for its release date.[41] Collins recalled: "I'd be mixing and dubbing all night and then Tony and Mike would come in and remix what I'd done because I'd lost all sense of normality by that point".[34]

Story

[edit]

Gabriel used New York City as a tool to make Rael "more real, more extrovert and violent", choosing to develop a character that is the least likely person to "fall into all this pansy claptrap", and aiming for a story that contrasted between fantasy and character.[12][15] He explained that as the story progresses Rael finds he is not as "butch" as he hoped, and his experiences eventually bring out a more romantic side to his personality. Gabriel deliberately kept the ending ambiguous but clarified that Rael does not die, although he compared the ending to the buildup of suspense and drama in a film in which "you never see what's so terrifying because they leave it up in the air without ... labelling it".[15] Several of the story's occurrences and settings derived from Gabriel's own dreams.[42] Collins remarked that the entire concept was about split personality.[43] The individual songs also make satirical allusions to mythology, the sexual revolution, advertising, and consumerism.[42] Gabriel felt the songs alone were not enough to detail all of the action in his story, so he wrote the full plot on the album's sleeve.[12]

Plot summary

[edit]One morning in New York City, Rael is holding a can of spray paint, hating everyone around him. He witnesses a lamb lying down on Broadway which has a profound effect on him ("The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway"). As he walks along the street, he sees a dark cloud take the shape of a movie screen and move towards him, absorbing him ("Fly on a Windshield"). He sees an explosion of images of the current day ("Broadway Melody of 1974") before he wakes up in a cave and falls asleep once again ("Cuckoo Cocoon"). Rael wakes up and finds himself trapped in a cage of stalactites and stalagmites which close in towards him. As he tries to escape, he sees many other people in many other cages, before spotting his brother John outside. Rael calls to him, but John walks away and the cage suddenly disappears ("In the Cage").

Rael now finds himself on the floor of a factory and is given a tour of the area by a woman, where he watches people being processed like packages. He spots old members of his New York City gang, and also John with the number 9 stamped on his forehead. Fearing for his life, Rael escapes into a corridor ("The Grand Parade of Lifeless Packaging")[44] and has an extended flashback of returning from a gang raid in New York City,[45] a dream where his hairy heart is removed and shaved with a razor, ("Back in N.Y.C.") and his first sexual encounter ("Counting Out Time").[46] Rael's flashback ends, and he finds himself in a long, red-carpeted corridor of people crawling towards a wooden door. Rael runs past them and exits via a spiral staircase ("The Carpet Crawlers"). At the top, he enters a chamber with 32 doors, surrounded by people and unable to concentrate ("The Chamber of 32 Doors").

Rael finds a blind woman who leads him out of the chamber ("Lilywhite Lilith") and into another cave, where he becomes trapped by falling rocks ("Anyway"). Death arrives and gasses Rael with his supernatural anesthetic ("Here Comes the Supernatural Anaesthetist"). However, Rael believes himself to still be alive and escapes the cave, dismissing Death as a hallucination. Rael ends up in a pool with three Lamia, beautiful snake-like creatures, and has sex with them, but they die after drinking some of his blood. He eats their corpses ("The Lamia"). Leaving by the same door he came in through, he finds himself in a group of Slippermen, distorted, grotesque men who have all had the same experience with the Lamia, and say he has become one of them ("The Arrival"). Rael finds John among the Slippermen, who reveals that the only way to become human again is to visit Doktor Dyper and be castrated ("A Visit to the Doktor"). Both are castrated and keep their removed penises in containers around their necks. Rael's container is taken by a raven and he chases after it, leaving John behind. The raven drops the container in a ravine and into a rushing underground river ("The Raven").

As Rael walks alongside it, he sees a window in the bank above his head which reveals his home amidst the streets. Faced with the option of returning home, he sees John in the river below him, struggling to stay afloat. Rael dives in to save him and the gateway to New York vanishes ("The Light Dies Down on Broadway"). Rael rescues John and drags his body to the bank of the river and turns him over to look at his face, only to see his own face instead ("In the Rapids"). His consciousness then drifts between both bodies, and he sees the surrounding scenery melting away into a haze. Both bodies dissolve, and Rael's spirit becomes one with everything around him ("it.").[47]

Songs

[edit]Much of the music developed through band improvisations and mood-inspired jams, often after one member set a single idea. Examples of this are what Banks described as a "Chinese jam" which ended up sharing a track with "The Colony of Slippermen", one named "Victory at Sea" which was worked into "Silent Sorrow in Empty Boats", and another known as "Evil Jam" which became "The Waiting Room".[21][48] Though the album is written to a story concept, Gabriel described its format as being split into "self-contained song units".[17] He thought the album contained some of the group's best material that he was most proud of during his time in Genesis.[49]

Sides one and two

[edit]Opener "The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway" was the last song that schoolfriends Banks and Gabriel wrote together while Gabriel was in the group, although Gabriel maintained that he only wrote the lyrics.[50][51] Banks had to cross his hands over to play the piano introduction which has unusual sequences of notes.[52] The song borrows music and lyrics from "On Broadway" by The Drifters at the end.[53] "Fly on a Windshield" came from a group improvisation sparked by Rutherford's ideea of Egyptian pharaohs going down the Nile, which Hakcett compared to Maurice Ravel's Boléro.[21] Banks described the part where the entire band comes in, signifying the moment a fly hits the windshield of a car, as "probably the single best moment in Genesis's history."[54][19][55] The track segues into "Broadway Melody of 1974", although the two pieces were written independently and only connected later on.[55] Hackett and his brother John wrote the two opening chords of "Cuckoo Cocoon" at home several years prior, but John is uncredited.[56][57] Hackett wrote the vocal melody.[57] The music for "In the Cage" was almost entirely written by Banks, who presented it to the band only when it was nearly complete.[57]

"The Grand Parade of Lifeless Packaging" is one of the few songs on the album where the lyrics were written first, and the music was then composed to fit the theme.[58] According to Banks, "I just started playing these two chords, a dopey kind of riff really ... I just keep one note going through the whole thing and just change the chords underneath it, letting it build. Then what Pete did on top was kind of wild and he didn't really make any use of the melodic content of the piece, but I think it works very well."[57] While mixing at Island Gabriel asked Brian Eno, who was working on his album Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), to add synthesized effects on his vocals on several tracks, including "The Grand Parade of Lifeless Packaging".[59] Eno's work is credited on the liner notes for "Enossification".[33] Gabriel was a fan of Eno and believed he could enhance the adventurous aspect of the sound. Genesis had little money to pay Eno,[60] so Eno negotiated for Collins to play drums on his track "Mother Whale Eyeless".[61]

"Back in N.Y.C." saw Genesis adopt a more aggressive sound than before.[45] with Rutherford playing a 6-string Micro-Frets bass. Rutherford described "Back in N.Y.C." as a group composition which emerged from improvisations, while Banks said it was written entirely by Rutherford and himself, with Rutherford writing "the main parts".[62] Banks also credited Rutherford as the sole composer of "In the Rapids".[63] "Hairless Heart" originated from a guitar melody from Hackett, for which Banks composed the other parts as a backing.[64] Banks was fond of the piece and was dismayed when it was titled "Hairless Heart" in reference to a lyric from "Back in N.Y.C.", commenting, "shaving hair off the heart, it's a horrible concept!"[64] A rare instance of a Genesis song not written collaboratively, "Counting Out Time" was written entirely by Gabriel before the album was conceived.[64] Hackett's guitar solo was filtered through an EMS Synthi Hi-Fli guitar synthesizer.[65] "The Carpet Crawlers" developed at a time when Gabriel had written some lyrics, but no music had been written for them. Banks and Rutherford put together a chord sequence in D, E minor and F-sharp minor with a roll from the drums flowing through it.[66][19] Gabriel spent "hours and hours" on an out-of-tune piano at home developing the song, and his wife recalled his fondness for the track.[67][68] The beginning of the song reprises "The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway".[69]

Sides three and four

[edit]"Lilywhite Lilith" was built on two song fragments, both of them written by Collins–a section from the unrecorded early Genesis song "The Light", and a piece that he wrote later on.[70] "The Waiting Room" developed as a "basic good to bad soundscaping" jam while it was raining outside Headley Grange. When the band stopped, a rainbow had formed.[71] Collins remembered Hackett playing "these dark chords, then Peter blows into his oboe reeds, then there was a loud clap of thunder and we really thought we were entering another world or something. It was moments like that when we were still very much a unified five-piece."[19] Banks regretted not recording the improvisation as it took place, as he felt the band were unable to recreate the tone of the original in their later renditions.[72] "Anyway" developed from a song named "Frustration", which Banks wrote before Genesis was formed.[30][73] The music for "The Lamia" was primarily written by Banks. After he brought it to the band, Gabriel wrote the lyrics, and Banks brought it home to write the vocal melody.[74]

"The Colony of Slippermen" is divided into three parts, but also shares a track with the "Chinese jam" which was never given a proper title.[75] The synthesizer solo was developed as a joke, parodying traditional rock forms, but when played back the band found it sounded stronger than they had intended.[76] The riffs which precede "The Raven" were another element recycled from "The Light".[76] "Ravine" was another piece improvised by the band, with Hackett using a fuzz box and wah-wah pedal to emulate the sound of wind.[77] "The Light Dies Down on Broadway" is a reprise of "The Lamia" (the verses) and "The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway" (chorus), but the latter arranged at a slower tempo.[26] Rutherford and Banks wrote the lyrics, the only one on the album with lyrics by someone other than Gabriel, but were told by Gabriel what action had to take place in them.[26] "Riding the Scree" was played entirely by Banks, Collins, and Rutherford (apart from a brief vocal by Gabriel), with Rutherford playing both bass and guitar.[78] It was a particularly difficult track for Banks to play on stage due to its irregular meter with multiple time signature changes, so he played the solo in 4/4 time and hoped to end up with the rest of the band at the end.[26]

Genesis were unable to come up with ideas that they liked for a finale, so they settled for a piece Banks and Hackett wrote as an instrumental as the music for the closing track, "It".[79] The concluding lyric–"It's only knock and knowall, but I like it"–is a play on the contemporary song "It's Only Rock 'n Roll (But I Like It)" by The Rolling Stones.

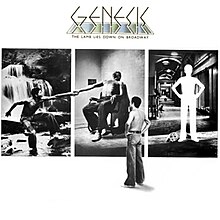

Sleeve design

[edit]The group's change in musical and artistic direction is also reflected visually, bringing in Hipgnosis to design the cover artwork. In contrast to previous Genesis album covers, which were colourful and more pastoral in nature, Hipgnosis conceived a monochrome design of a storyboard made of photographs depicting Rael in various settings from the story. The bottom left image depicts Rael in the area where "In the Rapids" and "Riding the Scree" are set.[34] Storm Thorgerson said the focal point of the design was having Rael step outside of it and looking back on the events, "a step considered necessary in the process of self-realisation."[80] The photographs were shot on black-and-white negative, of which the prints were cut, adjusted, and touched up with several artistic processes by Richard Manning to produce a final composite.[80][81][33] The band were adamant that they did not want to be photographed for the cover, and conducted a search for a model to portray Rael.[82] They went with an unnamed person who is credited as "Omar" on the liner notes.[33] The cover features a new band logo in an Art Deco style produced by George Hardie.

The band members had varying opinions of the album cover. Hackett considered it inferior to many of Hipgnosis's other covers and felt the style reflected an unwillingness by Hipgnosis to take the band's preferences into consideration. By contrast, Banks and Gabriel felt the cover was well-suited to the album, effectively highlighting that the music was in a much more stark and realistic style than their previous albums, though Gabriel said he was not fully satisfied with the model who portrays Rael. Collins called the cover "a little bit confused, just like the story. It's a distinct package and at least it evokes something."[82]

Release

[edit]The band considered releasing the album as two single albums released six months apart.[34] Gabriel later thought this idea would have been more suitable, for a double album contained too much new material, and the extra time would have given him more time to work on the lyrics.[34] Nevertheless, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway was released as a double album on 22 November 1974,[1] days after the start of its supporting tour. It peaked at No. 10 on the UK Albums Chart[83] in December 1974 during its six-week stay on the chart,[84] and became the band's highest-charting album yet in the US, peaking at No. 41 on the Billboard 200[85] in February 1975.[86] Elsewhere, the album reached No. 15 in Canada[87] and No. 34 in New Zealand.[88] Two singles were released; "Counting Out Time" with "Riding the Scree" as its B-side, was released on 1 November 1974.[34] The second, "The Carpet Crawlers" backed with a live performance of "The Waiting Room (Evil Jam)" at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, followed in April 1975. The album continued to sell, and reached Gold certification by the British Phonographic Industry on 1 February 1975,[89] and Gold by the Recording Industry Association of America for sales in excess of 500,000 copies on 20 April 1990.[90]

Critical reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | B−[91] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

Members of the group expressed some concern about the album's critical reception, and expected to receive some negative responses over its concept and extended format. Banks hoped the album would end people's comparisons of Genesis to Yes and Emerson, Lake & Palmer, two other popular progressive rock bands of the time. Gabriel knew the album's concept was ideal for critics "to get their teeth into".[93]

In giving an interview to Melody Maker in October 1974, shortly before the album's release, Gabriel played several tracks from The Lamb to reporter Chris Welch, including "In the Cage", "Hairless Heart", "Carpet Crawlers", and "Counting Out Time". Welch wrote, "It sounded superb. Beautiful songs, fascinating lyrics, and sensitive, subtle playing, mixed with humour and harmonies. What more could a Genesis fan desire?" He singled out Collins' playing as "outstanding".[17] Welch's review for Melody Maker published a month later included his thoughts on such long concept albums–"A few golden miraculous notes and some choice pithy words are worth all the clutter and verbiage"–and he called the album a "white elephant".[93] For New Musical Express, Barbara Charone wrote highly of the collection. She summarised The Lamb as a combination of the "musical proficiency" on Selling England by the Pound (1973) with the "grandiose illusions" on Foxtrot (1972) and "a culmination of past elements injected with present abilities and future directions". Charone thought it had more high points than any previous Genesis album, apart from some "few awkward instrumental moments on side three". All members received praise for their performances, including Hackett coming across as a more dominant member of the group with his "frenetic, choppy style", Collins' backup harmony vocals and Rutherford's "thick, foreboding bass chords and gentle acoustics".[94] Colin Irwin wrote a negative review of the "Counting Out Time" single, with its "weary, tepid approach" and a "woeful, dreary three and a half minutes".[95]

Legacy

[edit]In later years, the album received acclaim. In 1978, Nick Kent wrote for New Musical Express that it "had a compelling appeal that often transcended the hoary weightiness of the mammoth concept that held the equally mammoth four sides of vinyl together".[96] In a special edition of Q and Mojo magazines titled Pink Floyd & The Story of Prog Rock, The Lamb ranked at No. 14 in its 40 Cosmic Rock Albums list.[97] The album came third in a list of the ten best concept albums by Uncut magazine, where it was described as an "impressionistic, intense album" and "pure theatre (in a good way) and still Gabriel's best work".[98] AllMusic reviewer Stephen Thomas Erlewine gave a retrospective rating of five stars out of five. He says that despite Gabriel's "lengthy libretto" on the sleeve "the story never makes sense", though its music is "forceful, imaginative piece of work that showcases the original Genesis lineup at a peak ... it's a considerable, lasting achievement and it's little wonder that Peter Gabriel had to leave ... they had gone as far as they could go together".[86]

A Rolling Stone poll to rank readers' favourite progressive rock albums of all time placed The Lamb fifth in the list.[99] In 2014, readers of Rhythm voted it the album with the fourth-greatest drumming in the history of progressive rock.[100] In 2015, NME included the album in its "23 Maddest and Most Memorable Concept Albums" list for "taking in themes of split personalities, heaven and hell and truth and fantasy".[101] It was one of two albums by Genesis included in the top ten of the Rolling Stone list of the 50 Greatest Prog Rock Albums of All Time. The magazine described it as "one of rock's more elaborate, beguiling and strangely rewarding concept albums".[102] The album was also included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[103]

Banks later thought the album's concept the weakest thing about it, though the lyrics to some of the individual songs are "wonderful".[104] Rutherford said that, while The Lamb is a fan favorite, it was a gruelling album to work on and had a lot of highs, but also a lot of lows. Hackett remarked how his guitar was underutilized in comparison to past albums, but thought the album had a lot of beautiful moments and has grown on him over time. In Genesis: Together and Apart, Gabriel said The Lamb and the song "Supper's Ready" were his high points with Genesis. Collins said it was Genesis's best music and his favourite Genesis album.[105]

Reissues

[edit]The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway was first remastered for CD in 1994, and released on Virgin Records in Europe and Atlantic Records in North America. The included booklet features the lyrics and story printed on the original LP, though some of the inner sleeve artwork was not reproduced. A remastered edition for Super Audio CD and DVD with new stereo and 5.1 surround sound mixes by Nick Davis was released in 2008 as part of the Genesis 1970–1975 box set.

In 2024, Genesis announced the 50th Anniversary Super Deluxe Edition. This edition will include a new remaster of the album, a full live concert from the Shrine Auditorium (previously released on Genesis Archive 1967–75), a blu-ray version of the album in Dolby Atmos and "three previously unreleased demos" from the Headley Grange sessions included on a digital download card. Also included is a 60-page book, featuring notes by Alexis Petridis, a band member commentary and "rare images", and a 1975 tour programme, poster and replica ticket. This reissue is set to be released on 28 March 2025.[106]

Tour

[edit]Genesis supported the album with a 102-date concert tour across North America and Europe,[107] playing the album in its entirety with one or two older songs ("The Musical Box", sometimes followed by "Watcher of the Skies") as encores.[108][109] Rutherford said he was weary of this format by the end of the tour, preferring to play songs from a variety of eras and have the freedom to change up the setlist mid-tour.[110] In addition, most of the audience were not yet familiar with the large amount of new material; in particular, the North American leg of the tour was conducted before the album had been released there.[111] 29 October 1974 was to begin an 11-date tour of the UK that sold out within four hours, but after Hackett crushed a wine glass in his left hand which severed a tendon, and needed time to recover, these dates were rescheduled for 1975. The group lost money, for they were unable to recoup deposits they had paid to the venues.[112][17] The tour began on 20 November in Chicago,[68] and ended on 22 May 1975 in Besançon, France.[107] The last scheduled concert, on 24 May in Toulouse, was cancelled due to low ticket sales.[43][113] All but one date of an extensive tour of Italy was also cancelled, due to political turmoil.[114] Hackett estimated the band's debts at £220,000 at the tour's end.[115]

The tour featured at the time some of the biggest instruments used by the band, including Rutherford's double-neck Rickenbacker and the largest drum kit ever used by Collins. The tour's stage show involved three backdrop screens that displayed 1,450 slides, designed by Geoffrey Shaw, from eight projectors[116] and a laser lighting display.[117] Banks and Collins recalled the slides only came close to working perfectly on four or five occasions.[43][111] Gabriel changed his appearance with a short haircut and styled facial hair[17] and dressed as Rael in a leather jacket, T-shirt and jeans. During "The Lamia", he surrounded himself with a spinning cone-like structure decorated with images of snakes.[118] In the last verse, the cone would collapse to reveal Gabriel wearing a body suit that glowed from lights placed under the stage. "The Colony of Slippermen" featured Gabriel as one of the Slippermen, covered in lumps with inflatable genitalia that emerged onto the stage by crawling out of a penis-shaped tube.[42] Gabriel had difficulty placing his microphone near his mouth whilst he was in the costume.[43] Even on those occasions when Gabriel's mouth reached the microphone, and he did not get stuck coming out of the tube or trip and fall due to the poor visibility, he was too out of breath from his struggles with the costume to sing properly.[109] Between the end of "In the Rapids" and the start of "It", an explosion set off twin strobe lights that revealed Gabriel and a dummy figure dressed identically on each side of the stage, leaving the audience clueless as to which was real. The performance ended with Gabriel vanishing from the stage in a flash of light and a puff of smoke.[43] At the final concert, roadie Geoff Banks acted as the dummy on stage, wearing nothing but a leather jacket.[30] Tony Banks felt this prank was in poor taste.[113]

In one concert review, the theatrics for "The Musical Box", the show's encore and once the band's stage highlight, was seen as "crude and elementary" compared to the "sublime grandeur" of The Lamb... set.[119] Music critics often focused their reviews on Gabriel's theatrics and took the band's musical performance as secondary, which irritated the rest of the band.[120] Collins later said, "People would steam straight past Tony, Mike, Steve and I, go straight up to Peter and say, "You're fantastic, we really enjoyed the show." It was becoming a one-man show to the audience."[30] The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame called the tour "a spectacle on par with anything attempted in the world of rock to that point".[121]

Gabriel's departure

[edit]During their stop in Cleveland in November 1974, Gabriel told the band he would leave at the conclusion of the tour.[108] The decision was kept a secret from outsiders and media all through the tour, and Gabriel promised the band to stay silent about it for a while after its end in June 1975, to give them some time to prepare for a future without him. By August, the news had leaked to the media anyway, and Gabriel wrote a personal statement to the English music press to explain his reasons and his view of his career up to this point; the piece, titled "Out, Angels Out", was printed in several of the major rock music magazines.[122] In his open letter, he explained his disillusion with the music industry and his wish to spend extended time with his family.[123] Banks later stated, "Pete was also getting too big for the group. He was being portrayed as if he was 'the man' and it really wasn't like that. It was a very difficult thing to accommodate. So it was actually a bit of a relief."[108]

Recordings

[edit]No complete performance of the album has been officially released, though the majority of the band's performance from 24 January 1975 at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles appears on the Genesis Archive 1967–75 box set.[124] Some tracks feature re-recorded vocals from Gabriel and guitar parts from Hackett, while the rendition of "It" was replaced with a remixed studio version with re-recorded vocals.

Canadian tribute band The Musical Box has performed the album in its entirety on several tours using the slides from the original performances.

Track listing

[edit]All tracks written by Tony Banks, Phil Collins, Peter Gabriel, Steve Hackett and Mike Rutherford.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway" | 4:48 |

| 2. | "Fly on a Windshield" ([a]) | 2:45 |

| 3. | "Broadway Melody of 1974" | 2:11 |

| 4. | "Cuckoo Cocoon" | 2:11 |

| 5. | "In the Cage" | 8:14 |

| 6. | "The Grand Parade of Lifeless Packaging" | 2:47 |

| Total length: | 22:56 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Back in N.Y.C." | 5:44 |

| 2. | "Hairless Heart" | 2:10 |

| 3. | "Counting Out Time" | 3:42 |

| 4. | "Carpet Crawl" ([b]) | 5:15 |

| 5. | "The Chamber of 32 Doors" | 5:40 |

| Total length: | 22:31 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Lilywhite Lilith" | 2:45 |

| 2. | "The Waiting Room" | 5:22 |

| 3. | "Anyway" | 3:08 |

| 4. | "Here Comes the Supernatural Anaesthetist" ([c]) | 3:00 |

| 5. | "The Lamia" | 6:57 |

| 6. | "Silent Sorrow in Empty Boats" | 3:07 |

| Total length: | 24:16 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Colony of Slippermen"

| 8:13 |

| 2. | "Ravine" | 2:04 |

| 3. | "The Light Dies Down on Broadway" | 3:33 |

| 4. | "Riding the Scree" | 3:57 |

| 5. | "In the Rapids" | 2:30 |

| 6. | "it." ([d]) | 4:14 |

| Total length: | 24:31 | |

Personnel

[edit]Genesis

- Peter Gabriel – lead vocals, flute

- Steve Hackett – guitars

- Mike Rutherford – bass guitar, 12-string guitar

- Tony Banks – keyboards, guitar

- Phil Collins – drums, percussion, vibraphone, backing vocals

Additional musician

Production

- John Burns – production

- Genesis – production

- David Hutchins – engineer

- Hipgnosis – sleeve design, photography

- Graham Bell – choral contribution

- "Omar" – Rael on the album's artwork

- Richard Manning – cover retouching

- George Hardie – graphics (George Hardie N.T.A.)

- George Peckham (as "Pecko" and "Porky") – lacquer cutting

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1974–1975) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (Kent Music Report)[128] | 80 |

| Canada Top Albums/CDs (RPM)[87] | 15 |

| Finnish Albums (The Official Finnish Charts)[129] | 17 |

| French Albums (SNEP)[130] | 1 |

| Italian Albums (Musica e dischi)[131] | 14 |

| New Zealand Albums (RMNZ)[132] | 34 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[133] | 10 |

| US Billboard 200[134] | 41 |

| Chart (2014) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| UK Rock & Metal Albums (OCC)[135] | 17 |

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Canada (Music Canada)[136] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| France (SNEP)[137] | Gold | 100,000* |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[138] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[139] | Gold | 500,000^ |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

Notes

[edit]- ^ Several later pressings of the album lists "Fly on a Windshield" at 4:23 and "Broadway Melody of 1974" at 0:33, an error by the manufacturer as "Broadway Melody of 1974" begins at 2:47 of "Fly on a Windshield". The lyrics printed on the sleeve give the correct division between the two tracks.

- ^ The original UK pressing lists the track as "Carpet Crawl".[33] The single worldwide and the original US pressing lists the track as "The Carpet Crawlers".[125] Was changed to "Carpet Crawlers" worldwide on the 1994 remaster.[126]

- ^ The US pressing lists the track as "The Supernatural Anaesthetist".[125]

- ^ The song's title is typeset in lowercase in the album's booklet, which presents the titles of every other song in title case. On the back cover it is presented in all caps, the same as all other songs, but is the only one in italics.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Mic Smith (May 2017). "Get 'Em Out By Friday. Genesis: The Official Release Dates 1968-78" (PDF). pp. 57–61. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ "The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway". petergabriel.com. 20 November 2024. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ Allen, Jim (4 January 2017). "Genesis Albums Ranked Worst to Best". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ Rutherford 2015, p. 120.

- ^ Clarke, Steve (1 June 1974). "The Charterhouse Boys". New Musical Express. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ a b Genesis 2007, p. 151.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 214.

- ^ Rutherford, Mike. Reissues Interview 2007 bonus feature at 4:22–4:45.

- ^ a b Takiff, Jonathan (4 December 1974). "Genesis of a rock 'n' roll band". Philadelphia Daily News. p. 23. Retrieved 23 February 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Banks, Tony. Reissues Interview 2007 bonus feature at 4:45–5:05.

- ^ Platts 2001, p. 74, 75.

- ^ a b c d Charone, Barbara (26 October 1974). "Mickey Mouse Lies Down on Broadway". Sounds. pp. 22, 27. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ Welch, Chris. Genesis: The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway. Melody Maker, 23 November 1974.

- ^ a b Easlea, Daryl (23 April 2007). "Classic Pop/Rock Review – Genesis, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway". BBC. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- ^ a b c d Bell, Max (15 March 1975). "Gabriel's Cosmic Juice (not to be taken internally)". New Musical Express. pp. 14–15. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 88.

- ^ a b c d e Welch, Chris (26 October 1974). "The New Face of Gabriel". Melody Maker. pp. 28–29. Retrieved 22 April 2016. Note: In the article Gabriel erroneously refers to a "character" named Rael, but "Rael" in the Who song is actually a place.

- ^ a b Spencer, Neil (2 November 1974). "Public school boy reprimands critics". New Musical Express. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d Genesis 2007, p. 157.

- ^ Erskine, Pete (30 November 1974). "GENESIS: "The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway" (Charisma)". New Musical Express. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ a b c Hewitt 2001, p. 42.

- ^ Banks, Tony. Reissues Interview 2007 bonus feature at 5:15–5:25.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 211-212.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 213-214.

- ^ Collins, Phil. Reissues Interview 2007 bonus feature at 2:07–2:28.

- ^ a b c d Giammetti 2020, p. 233.

- ^ a b c Platts 2001, p. 75.

- ^ a b Giammetti 2020, p. 216.

- ^ Collins, Phil. Reissues Interview 2007 bonus feature at 8:36–9:20.

- ^ a b c d Genesis 2007, p. unknown.

- ^ Murray, Matthew (3 February 2017). "Genesis studio manor house in Capel Iwan up for £1.1m". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ "Glaspant Retreats Gallery". www.glaspant.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway (Media notes). Charisma Records. 1974. CGS 101.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Holm-Hudson 2008, p. 52.

- ^ Rutherford, Mike. Reissues Interview 2007 bonus feature at 14:42–15:15.

- ^ Collins, Phil. Reissues Interview 2007 bonus feature at 15:15–15:32.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 217.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 217-218.

- ^ Rutherford 2015, p. 122.

- ^ Gabriel, Peter. Reissues Interview 2007 bonus feature at 10:55–12:30.

- ^ a b Platts 2001, p. 76.

- ^ a b c Platts 2001, p. unknown.

- ^ a b c d e Genesis (1991). Genesis: A History (VHS). PolyGram Video.

- ^ Holm-Hudson 2008, p. 72.

- ^ a b Holm-Hudson 2008, p. 75.

- ^ Holm-Hudson 2008, p. 76.

- ^ "bloovis.com – The Annotated Lamb Lies Down on Broadway". www.bloovis.com. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Genesis 2007, p. 156.

- ^ Gabriel, Peter. Reissues Interview 2007 bonus feature at 16:34–16:52.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 213.

- ^ Banks, Tony. Reissues Interview 2007 bonus feature at 17:39–17:51.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 221.

- ^ Holm-Hudson 2008, p. 65.

- ^ Fielder & Sutcliffe 1984.

- ^ a b Giammetti 2020, p. 222.

- ^ Herlitschka, Paul. ""The trip to Alsace was a major part of Moonspinner"". Genesis France. Association Genesis France. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d Giammetti 2020, p. 223.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 223-224.

- ^ Holm-Hudson 2008, p. 58.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 224.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 117.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 224-225.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 234.

- ^ a b c Giammetti 2020, p. 225.

- ^ Platts 2001, p. 77.

- ^ Banks, Tony. Reissues Interview 2007 bonus feature at 19:31–19:59.

- ^ Gabriel, Peter. Reissues Interview 2007 bonus feature at 19:59–20:25.

- ^ a b Bright, Spencer (1999). Peter Gabriel: An Authorized Biography. Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0-283-06187-1. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 227.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 228.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 92.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 229.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 230.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 230-231.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 231.

- ^ a b Giammetti 2020, p. 232.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 232-233.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 233-234.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 234-235.

- ^ a b "Genesis: The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway". Hypergallery. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ "Genesis - Lamb Lies Down on Broadway 1974". RichardManning.co.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- ^ a b Giammetti 2020, p. 235-236.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 246.

- ^ "Genesis". Official Charts. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ "Genesis: Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2011). "The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway". AllMusic. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ a b "Top RPM Albums: Issue 3919a". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ "GENESIS – THE LAMB LIES DOWN ON BROADWAY (ALBUM)". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ "Certified Awards". British Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "GOLD & PLATINUM: The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). "Consumer Guide '70s: G". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 089919026X. Retrieved 24 February 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ Nathan Brackett; Christian David Hoard (2004). The new Rolling Stone album guide. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 327. ISBN 978-0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ a b Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 94.

- ^ Charone, Barbara (25 November 1974). "Genesis: lamb like a polished diamond". Sounds. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Irwin, Colin (16 November 1974). "Genesis: What a dreary time". Melody Maker. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Nick Kent: "Gabriel: The Image Gets a Tweak". New Musical Express. 10 June 1978

- ^ Q Classic: Pink Floyd & The Story of Prog Rock, 2005.

- ^ Uncut magazine. May 2007. Issue 120.

- ^ Greene, Andy. "Readers' Poll: Your Favorite Prog Rock Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ "Peart named most influential prog drummer". TeamRock. 3 October 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ "23 Of The Maddest And Most Memorable Concept Albums". NME. 8 July 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ "50 Greatest Prog Rock Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ Easlea, Daryl (2006). "Genesis: The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway". In Dimery, Robert (ed.). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die. Universe Publishing. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-7893-1371-3.

- ^ Banks, Tony. Reissues Interview 2007 bonus feature at 2:33–2:45.

- ^ "Phil Collins". IMDb. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ "Announcing 'The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway (50th Anniversary Super Deluxe Edition)' - 28.03.25". YouTube. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ a b Genesis 2007, p. 349.

- ^ a b c Genesis 2007, p. 158.

- ^ a b Giammetti 2020, p. 242.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 241-242.

- ^ a b Giammetti 2020, p. 241.

- ^ "Genesis tour is called off!". New Musical Express. 26 October 1974. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ a b Giammetti 2020, p. 247.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 246.

- ^ Platts 2001, p. 82.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 100.

- ^ Platts 2001, p. 95.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 244.

- ^ Rudis, Al (7 December 1974). "Impressive Genesis hit new heights". Melody Maker. p. 28. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 93.

- ^ "Genesis Biography". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ Eric (13 February 2012). "Peter Gabriel's letter to media on why he left Genesis". That Eric Alper. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 107.

- ^ Platts 2001, p. 81.

- ^ a b The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway (Media notes). Atco Records. 1974. SD 2-401.

- ^ The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway [1994 Remaster] (Media notes). Virgin Records. 1974. CGSCDX 1.

- ^ Stone, Greg. "Tony Banks Interview April 1978". YouTube. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 19. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ Pennanen, Timo (2006). Sisältää hitin – levyt ja esittäjät Suomen musiikkilistoilla vuodesta 1972 (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava. p. 166. ISBN 978-951-1-21053-5.

- ^ "Le Détail des Albums de chaque Artiste – G". Infodisc.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2012. Select Genesis from the menu, then press OK.

- ^ "Classifiche". Musica e dischi (in Italian). Retrieved 10 March 2024. Set "Tipo" on "Album". Then, in the "Titolo" field, search "The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway".

- ^ "Charts.nz – Genesis – The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ "Genesis Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ "Official Rock & Metal Albums Chart Top 40". Official Charts Company. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Genesis – The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway". Music Canada. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ "French album certifications – Genesis – The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway" (in French). InfoDisc. Retrieved 5 December 2016. Select GENESIS and click OK.

- ^ "British album certifications – Genesis – The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ "American album certifications – Genesis – The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Banks, Tony; Collins, Phil; Gabriel, Peter; Hackett, Steve; Rutherford, Mike (2007). Dodd, Philipp (ed.). Genesis. Chapter and Verse. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84434-1.

- Bowler, Dave; Dray, Bryan (1992). Genesis – A Biography. Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 978-0-283-06132-5.

- Fielder, Hugh; Sutcliffe, Phil (1984). The Book of Genesis. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-08880-4.

- Giammetti, Mario (2020). Genesis 1967 to 1975 - The Peter Gabriel Years. Kingmaker. ISBN 978-1-913218-62-1.

- Hewitt, Alan (2001). Opening the Musical Box – A Genesis Chronicle. Firefly Publishing. ISBN 978-0-946-71930-3.

- Holm-Hudson, Kevin (2008). Genesis and The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-754-66139-9.

- Platts, Robin (2001). Genesis: Inside & Out (1967–2000). Collector's Guide Publishing. ISBN 978-1-896-52271-5.

- Rutherford, Mike (2015). The Living Years: The First Genesis Memoir. Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-1-250-06068-6.

- Thompson, Dave (2004). Turn It On Again: Peter Gabriel, Phil Collins, and Genesis. Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-810-9.

DVD media

- Banks, Tony; Collins, Phil; Gabriel, Peter; Hackett, Steve; Rutherford, Mike (10 November 2008). Genesis 1970–1975: The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway (DVD). Virgin Records. UPC 5099951968328.