English Armada

| English Armada | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo–Spanish War (1585–1604) | |||||||

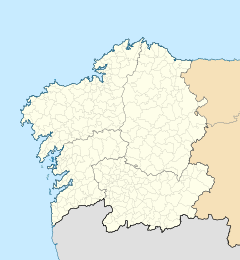

Map of the English Armada campaigns | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

900 dead or wounded 3 galleons destroyed[11] 13 merchant ships | |||||||

The English Armada (Spanish: Invencible Inglesa, lit. 'Invincible English'), also known as the Counter Armada or the Drake–Norris Expedition, was an attack fleet sent against Spain by Queen Elizabeth I of England that sailed on 28 April 1589 during the undeclared Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) and the Eighty Years' War. Led by Sir Francis Drake as admiral and Sir John Norris as general, it failed to drive home the advantage that England had gained resulting from the failure of the Spanish Armada in the previous year. The Spanish victory marked a revival of Philip II's naval power through the next decade.[12]

Background

[edit]| Opposing monarchs |

|---|

After the failure of the Spanish Armada and its return to Spain, England's Queen Elizabeth I's intentions were to capitalize upon Spain's temporary weakness at sea and to compel King Philip II of Spain to negotiate for peace. Her advisors had more ambitious plans. William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley noted that the expedition had three main objectives: destroy the battered Spanish Atlantic fleet, which was being repaired in ports of northern Spain; make a landing at Lisbon and raise a revolt there against Philip II (Philip I of Portugal); and to continue west and establish a permanent base in the Azores.[13][14] A further aim was to seize the Spanish treasure fleet as it returned from the Americas to Cádiz, but that depended largely on the success of the Azores campaign.[15][16]

The strategic objective of the military expedition was to break the trade embargo imposed across the Portuguese Empire, which included Brazil and the East Indies, and trading posts in India and China. By securing an alliance with the Portuguese crown, Elizabeth hoped to curb Spanish Habsburg power in Europe and to free up the trade routes to these possessions.[17] That was a difficult proposition because Philip had been accepted as king by the aristocracy and the clergy of Portugal in 1581 at the Cortes of Tomar. The pretender to the throne, António, Prior of Crato, the last surviving heir of the House of Aviz, had failed to establish an effective government-in-exile in the Azores, and turned to the English for support. He was not a charismatic figure, and with his cause compromised by his illegitimacy, he faced an opponent with a relatively strong claim to the throne in the eyes of the Portuguese nobles of the Cortes, Duchess Catherine of Braganza.

There were obstacles for the enterprise besides the complex politics. Burghley proposed launching a flotilla immediately. However, the English fleet was completely exhausted and crippled after preventing the Spanish invasion attempt and Elizabeth's coffers were empty.[18] Furthermore, like its Spanish predecessor, the English expedition suffered from unduly optimistic planning, based on hopes of repeating Drake's successful raid on Cadiz in 1587. There was a contradiction between the separate plans, each of which was ambitious in its own right, but the most pressing need was the destruction of the Spanish Atlantic fleet lying at port in A Coruña, San Sebastián and Santander along the northern coast of Spain, as was directly ordered by the Queen.

Since Elizabeth had no resources, Drake and Norris floated the expedition as a joint stock company, with capital of about £80,000, one quarter to come from the Queen and one eighth from the Dutch, the balance to be made up by various noblemen, merchants and guilds.[14]The treasurer was Sir James Hales, who died on the return journey, as is recorded on his monument in Canterbury Cathedral. Concerns over logistics and the adverse weather delayed the departure of the fleet, and confusion grew as it waited in port. The Dutch failed to supply their promised warships, a third of the victuals had already been consumed, and the ranks of volunteers had increased the planned contingent of troops from 10,000 to 20,000+.[14] Unlike the Spanish Armada expedition the previous year, the English fleet also lacked siege guns and cavalry, which would compromise its intended aims.

Execution

[edit]Assembling the attack force

[edit]Ships

[edit]

As recorded on the list of 8 April 1589 o.s.[Note b], there were Royal galleons, English armed merchantmen, Dutch flyboats, pinnaces and other ships for a total of 180 vessels broken down thusly:[4]

| Troops and mariners | 115 |

| Baggage | 33 |

| Horses | 10 |

| Victuals | 10 |

| Munitions | 2 |

| Support | 3 |

| Pioneers | 7 |

The list of 9 April o.s. names 84 ships divided amongst five squadrons led respectively by Drake in the Revenge, Sir John Norris in the Nonpareil, Norris' brother Edward in the Foresight, Thomas Fenner in the Dreadnought, and Roger Williams in the Swiftsure., each with "near about 15 flyboats", which would give a total of about 160.[19] However, in the payment list of 5 September 1589 o.s., there are 13 ships named that were not on the 9 April o.s. list.[20] Those 13 ships were not flyboats hence they should be added to the 160 from the 9 April o.s. list. With expectations of sizable profit and this expedition being mostly commercial, and last minute additions being made up until the fleet sailed on 28 April, one cannot really give a precise total number of ships but at least 173 can be documented. Nevertheless, what is rather telling is a 15 February 1591 o.s. notice to the Lord High Treasurer of England, Burghley, wherein the number of vessels was "180 and other ships".[21] It's not outside the realm of possibility that the number "reached nearly two hundred sail."[22]

Men

[edit]In the 8 April o.s. list, there were two different figures recorded for the number of men participating in the expedition. The first, 23,375, is what most historians and authors have used however at the end of this document, the total number of men had increased to 27,667.[4] A critical analysis of the document reveals the figure of 23,375 is illusory,[23] especially when below the signatures of Drake and Norris, and the confirmation of the Lord High Treasurer Burghley, there's the following postscript:

Signed J. Norris, F. Drake. Endorsed by Burghley as 8 April 1589. The numbers of men for the army and of ships and of foot at end in his hand 27,667.[4]

The story of how Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, ended up sailing with them almost parallels that of the English Armada itself. Against the Queen's express orders, the 21-year old Devereux eagerly escaped from his rich capricious lover and embarked on what he thought was sure to be an exciting and profitable adventure. The Earl of Essex hid on the Swiftsure and Drake, Norris nor Williams betrayed the Earl when the Queen's courtier Francis Knollys came to Plymouth looking for him. The Swiftsure set sail immediately upon hearing Knollys declarations.[24] By the time Knollys set out in a pinnace in pursuit, nobody knew where the Swiftsure was because a strong wind forced it into Falmouth. The English fleet set sail without the Swiftsure, which sailed two days later and headed straight for the Portuguese coast to rendezvous with the rest of the fleet.[25]

Coruña

[edit]

Of the 137[26] ships of Philip II's expedition of 1588 that entered the English Channel, most of the 29 ships lost had been armed merchantmen, and the core of the Armada, the galleons of the Squadron of Portugal of the Armada del Mar Oceano (Atlantic Fleet), survived their voyage home and docked in Spain's Atlantic ports for repairs, where they lay for months and were vulnerable to attack.[16]

Drake and Norris had orders from Queen Elizabeth to first attack Santander, where most of the surviving galleons from the Spanish Armada were being kept, and destroy the Spanish fleet. He also had to placate the fleet's commanders and investors who wanted the first objective to be landing in Lisbon.[27] Drake chose to ignore them, alleging unfavourable winds and too much risk of becoming embayed by the Spaniards in the Bay of Biscay. He chose to bypass Santander and headed in a different direction to attack Coruña,[28] in Galicia instead. It is not completely clear why he did this, even though the winds seem like a poor excuse. His behaviour suggests that his goal in taking this city was either to establish a base of operations or to raid it for booty. The latter seems most plausible since this expedition was privately funded and Drake had investors to satisfy. He may have been gathering supplies for a long struggle in Santander.[29] Either way, this decision was the campaign's first major error.

Whilst crossing the Bay of Biscay some 25 ships with 3,000 men deserted,[30] including many of the Dutch who found reasons to return to England or put into La Rochelle.[31] Coruña was almost defenceless at the time of the attack. To face the rest of the English Armada's ships, except the Swiftsure, plus boats and the soldiers in them, Coruña had one large galleon undergoing repairs (San Juan, with 50 cannons), two galleys (Diana and Princesa, with 20 cannons each), the 1,300 ton carrack Regazona, and three other smaller ships (nao San Bartolomé with 27 cannons, the urca Sansón with 18 cannons and the galeoncete (small galleon) San Bernardo with 21 cannons). Juan Pacheco de Toledo, Marques de Cerralbo, the governor of Coruña, and garrison commander Álvaro Troncoso led a combination of militia, hidalgos and the few available soldiers totaled 1,200 troops, most of them with little military training, except for seven companies of old tercios, who happened to be resting in the city after their return from war. It also had the medieval city walls, built in the 13th century.[32]

The English entered the bay of Coruña and disembarked on 4 May. Norris took the lower town, inflicted 500 casualties and plundered the wine cellars and fisheries there, and Drake destroyed the galleon Regazona, the San Bartolome and thirteen merchant ships in the harbour. The Spanish set the unseaworthy San Juan on fire, not before dismounting her guns to use them against the English fleet and troops. For the next two weeks, the wind blew westerly, and while waiting for a change, the English occupied themselves in a siege of Coruña's fortified upper town. Norris' troops launched three major assaults against the walls of the upper town and tried to breach them with mines, but the vigorous defence by the regular Spanish troops, militia, and women of the city, including Maria Pita and Inés de Ben,[33] forced the English back with severe losses.[34] The Spanish then attempted to reinforce the garrison through the bridge of El Burgo, but they were intercepted by a force of 6,000 men led by John and Edward Norreys, and with push of the pike were defeated with heavy losses.[35][36]

The Princesa and the Diana managed to avoid capture and slipped past the English fleet; according to English sources, they repeatedly resupplied the defenders unmolested.[6] On the 18th, after 14 days of siege and attempted assaults, the English heard news about a fresh Spanish relief force on their way to Coruña,[37] and at length, with a favourable wind returning and painfully low morale, the English abandoned the siege and retreated to their ships after they had lost four captains, three large ships,[16] various boats[16] and more than 1,500 men in the fighting alone.[38] After investing two-weeks attempting to capture this "simple" fishing town of 4,000 people, outnumbering their fighting forces by more than 10:1, Drake left without even loading up on supplies.[39] Next stop, Portugal where, along the way, the fleet met up with Essex and the Swiftsure.

Portugal

[edit]

Work to strengthen the fortifications of São Julião, Oeiras, Trafaria and Caparica which defended the entrance to the Tagus estuary had been completed by 20 May.[40] Philip II's viceroy in Portugal was Archduke Albert VII who tasked João Gonçalves de Ataide to recruit local men to defend against the impending invasion and ordered Captain Pedro Enríquez de Guzmán, Count of Fuentes to bring a few Spanish companies.

Meanwhile, Drake struggled against the wind. Three days after leaving Coruña, a south-westerly wind caused part of the fleet to drift towards Estaca de Bares and the coast of Lugo, leaving it somewhat dispersed. It wasn't until 24 May that the bulk of the fleet managed to sail beyond Cape Finisterre where they came upon Essex and the Swiftsure, then, with a favourable wind, headed for Lisbon.[41]The next day, 25 May, just off the island of Berlengas, they spotted Cape Roca indicating the Tagus estuary was not far off.[42] By the end of the day, the fleet anchored in the bay of Peniche where a war council was held.

The next step in Elizabeth's plan was to arouse a Portuguese uprising against Philip II. The Portuguese aristocracy had recognized the latter as King of Portugal in 1580 and thus added the Kingdom of Portugal to the Hispanic Monarchy. The pretender to the throne who England supported, the Prior of Crato, was not the best candidate. He did not have enough support even to establish a government-in-exile or much charisma to back his already-dubious claim. Despite this, Elizabeth had agreed to help him in hopes of diminishing the power of the Spanish Empire in Europe and for a permanent military base in the strategic Azores, from which to attack merchant ships and to obtain ultimate control of the commercial routes to the New World.[31]

In the wake of their experience in Coruña, Drake and Norris clashed on how to achieve this next objective. Despite Drake having proven success against Spanish forces whereas Norris had none, the fleet went with Norris' plan. They would land in Peniche then march 70 km (43 mi) south to attack Lisbon by land while Drake attacked from the sea. This was the fleet's second major error.

Landing at Peniche

[edit]

On 26 May, Drake arrived at Peniche. Ataíde had marshalled just over 400 troops in preparation of the fleet's arrival. He and his men knew the coastline well and were deployed in the areas where a landing would be easiest while Antônio de Araújo remained in the fortress of Peniche.[43] The English, led by the Earl of Essex, took thirty-two barges to the most dangerous point of Consolação beach which was completely exposed to the sea, rocky coastline and deep water. Fourteen barges foundered and others were smashed against the reefs, 80 men drowned but the English managed to establish a beachhead where the first skirmish took place.[44] Captain Benavides immediately engaged some 2,000 invaders with 100 men. Ataíde brought his 400 men and Captain Blas de Jerez added another 80 while Pedro de Guzmán stayed in the rearguard. Ataíde led three bloody charges, afterwards making an orderly withdrawal, leaving fifteen Spaniards dead on the battle field. Ataíde and Guzmán headed for the fort of Peniche and discovered it was surrounded by the English. Their only way out was to withdraw in the direction of the village of Atouguia da Baleia and in the fields outside the town, they camped for the night. The English had swept in like a hurricane and had landed 12,000 men in a matter of hours.[45] The English offered terms of surrender to Captain Araújo, commander of Peniche's fortress garrison who responded he would only surrender to the pretender Dom António, which he did.[46] That same day, Archduke Albert ordered Alonso de Bazán to bring 12 galleys with more infantry to São Julião. During the night, the men recruited by Ataíde deserted.

The Spanish had their doubts about their Portuguese allies. They weren't exhibiting the expected fervour against this invader. There was no love lost regarding the Prior of Crato; he not only squandered the Portuguese crown jewels which he took when he fled the country, but he promised to Elizabeth the subjection of the Portuguese empire along with a permanent pecuniary payment.[47] The impression made by the return of the pretender with an enormous invading army was conflicting. The Portuguese didn't rise up in revolt and join ranks as Dom António had promised but they weren't eager to be part of the Spanish resistance either.[48] The next morning, Captain Gaspar de Alarcón led his Spanish cavalry on a surprise attack against the English flank, capturing a few prisoners whereupon Guzmán withdrew to the fortress of Torres Vedras and sent Ataíde to report to the Archduke in Lisbon.

Norris' march to Lisbon

[edit]Norris had stationed 500 men with six ships in Peniche[49] then the English began their long march to Lisbon on 28 May without artillery or a baggage train making provisioning problematic but Dom António assured them that the locals would provide whatever the army needed. The English had very strict orders not to upset the inhabitants but housebreaking and pillaging was rife once they were clear of Peniche. Norris ordered Captain Crisp, the provost marshal, to hang the perpetrators including their officers.[50][51] As they approached Torres Vedras, Guzmán and Don Sancho Bravo, who brought more cavalry and infantry, withdrew to Enxara dos Cavaleiros some two leagues away while Alarcón stayed behind to harass the enemy and report on their actions.[52] Dom António made his triumphal entry into Torres Vedras on 29 May with much fanfare from the people but the English commanders and nobles noticed something was off. They realized that Portuguese nobility were not amongst the revellers; in fact, they were nowhere to be found.[53] These were precisely the individuals who, along with their conscripts, were to set the example for the population to rise up in favour of the Prior of Crato.[54] The English pressed Crato about provisioning whereupon the latter had sent soldiers to fetch the lawyer, Gaspar Campello, living nearby and put him in charge of provisioning the army. Campello had no better success in gathering provisions since the local population were leaving with their possessions and supplies thus leaving the road to Lisbon devoid of victuals. Meanwhile, in Lisbon, the population was fleeing with much of their moveable property in anticipation of the English overrunning the city thus leaving the defence of the city to the Spaniards.[55]

On 30 May, Drake reached the port of Cascais and anchored his fleet between its citadel and that of São Julião in a crescent formation as close to the coast as possible. He also ordered raiding vessels to scour the waters of the nearby coastline and the Berlengas islands for enemy ships. Meanwhile, the English army, continually harassed by the Spaniards during their arduous journey, reached Loures, barely 10 km (6.2 mi) from the walls of Lisbon.[56] Though their perilous journey was behind them, the Spanish would not allow them to enjoy much rest for their camp continued to be attacked and any supplies cut off; Norris' army was getting hungrier by the minute. Little did the English know that just outside the city walls were vast stocks of supplies. Fearing the enemy would attack the next day and discover the storehouses along the way, the Archduke ordered Captain Don Juan de Torres to keep them occupied on 31 May whilst the provisions were brought into the city, and if de Torres could inflict losses on the English, all the better. Though the Spanish tried to coax the English into coming out of their trenches, the latter wouldn't move. Meanwhile, so as to deny the English any provisions, what remained in the storehouses after bringing what they could into Lisbon was set ablaze.[57] Because the English were not willing to come out and answer Spanish calls for battle, Captains Juan de Torres, Sancho Bravo, Gaspar de Alarcón and Francisco Malo selected 200 elite harquebusiers supported by some cavalry and carried out a camisado. Lieutenant Colonel John Sampson's camp was selected as the target of this mission. The Spanish approached the camp at dawn on Thursday, 1 June, Corpus Christi day, shouting "Viva el Rei Dom António!" (Long live Dom António!). The moment they were admitted into the camp, the guards were killed then several soldiers sleeping in their tents were killed before the alarm was shouted. The English hurriedly formed a makeshift defensive line while their compatriots were being massacred. Harquebus fire erupted on both sides and Don Juan de Torres was wounded in the arm; he died from it three-weeks later. The Spanish made a hasty retreat.[58]

While the English continued to rest and starve – the men found the weather too hot and exhausting, many were weak from hunger, sick and injured, and needed to be carried on baggage mules and stretchers made from pikes[59] –, the Archduke called a war council. The Portuguese commanders pointed out that since they were expecting relief troops to arrive any day, the city walls were tall and strong, and they could be easily resupplied from the Tagus while the English were suffering from hunger and sickness, they decided to bring the army within the city walls and make their stand there.[60][61] Before the end of day on 1 June the English were in Alvalade, less than an hour away, forming up pike squadrons.

Atop a high steep mound in Lisbon is the imposing and threatening Castle of São Jorge which commands an extraordinary view of the city and its environs. Installed within were new large reinforced bronze culverins with extra thick barrels pointed towards the English camp. The gunners needed to test the range of their new guns and found this an opportune time. Just as the English rearguard was leaving Alvalade on 2 June, the vanguard came within 2,000 metres (2,200 yards) and the guns were fired, causing surprise and inflicting casualties for Norris' army.[62] They quickly realized they'd be contending with this threat for as long as they were within range so a more suitable route with better cover was chosen to approach the city. Meanwhile, the Spanish had set fire to the houses built adjacent to the city's wall thus forming a makeshift bulwark and Bazán was ordered to bring 12 galleys from São Julião to the city. The English found a suburb that was suitably protected from the castle's artillery and that of the galleys where they camped for the night. Their rest was unsettled by a Spanish sortie leaving some English casualties on the field, before being chased away by the English cavalry and the Earl of Essex forces.[63][64]

While the troops tried to rest, plans were made to effect a surreptitious entry into the city. One Portuguese noble still loyal to Dom António was Rui Dias Lobo who took a message to the abbot and friars of the monastery of the Holy Trinity, which was built against a weak section of the city wall, asking for permission to use the monastery as an entry point for the English soldiers. Since the catholic friars were fully informed of the Protestant English treatment of Catholics, they discretely relayed this plan to the Spanish who in turn arrested and imprisoned Dias Lobo.[65] Another plan centered around a diversionary tactic and the betrayal of one of the Portuguese noble Matías de Alburquerque's captains who was in charge of one of the gates; nothing came of it. The third and least credible plan was the inhabitants would rebel the moment Dom António would reach the walls of Lisbon thus keeping the Spaniards inside the walls busy while the English entered without difficulty. None of these plans bore any fruit.[66][64]

Attack on Lisbon

[edit]

At dawn on 3 June, the English readied themselves to mount an assault on the western side of the city wall. In anticipation thereof, the Spanish stationed top marksmen on the rooftops of churches just outside the north-western sector to reinforce those on the western wall. The houses outside the gate of Santa Catalina were set on fire to prevent them from being used to scale the wall. The English then headed south toward the sea where preparations had been made for them. The houses there had also been burnt and the galleys were in position to rain fire down on them. When Norris finally got a good look at the vast outskirts of Lisbon and sheer size of the city, he could but only reflect. He had no artillery to smash through the wall nor scaling ladders to climb over the wall, in fact, he had no siege equipment of any kind. Moreover, his army's numbers were decreasing by the hour and those able to fight were weak from hunger.[67] The expected uprising by the Portuguese loyal to Crato never materialized[31] and Norris reluctantly admitted to himself that this campaign was a failure.[68] Their only option was to go on the defensive and withdraw to their trenches. This was the moment where the table turned and the Spanish went on the offensive.

Three simultaneous attacks were launched by the Spanish; one on the nearest most trenches in the very streets of the suburbs, one on the rear-guard, and the cannonade from the castle of São Jorge. The English suffered hundreds of losses whereas the Spanish left 25 dead.[69] The Spanish were expecting several thousand reinforcements on forced marches to arrive at any time and were continuously resupplied via the river whereas the English were out of powder and match.[70] The latter spent the day of 4 June burying their dead and planning a clandestine nocturnal retreat to Cascais. To execute the deception, they lit several bonfires in the campsite and kept them lit while the bulk of the infantry quietly scurried along a route away from the water and away from main roads so as not to be discovered. Meanwhile, the Archduke planned a feigne attack on the English camp because it seemed really peculiar to him that they hadn't made any offensive moves that entire day. He ordered that at midnight, the men on the galleys send 2,000 lit match cords on skiffs to land on the shore near the English camp. Normally, lit match cords at night would give away one's position but in this case, it was intended to make the English believe they were about to be attacked. It was a purely serendipitous coincidence that this ruse resulted in the enemy thinking their retreat had been discovered causing them to make disorderly haste.[71][72][73][74]

Withdraw to Cascais

[edit]As dawn broke on 5 June, Bazán's galleys spotted the enemy's movements and opened fire which awakened Lisbon. Upon determining that the enemy's withdraw was complete and not a trick, the Spaniards set out in pursuit. The galleys followed the English infantry firing all the while. When they approached Cascais, Sancho Bravo and Alarcón attacked the English column inflicting hundreds more casualties.[75] When the English completed the march from Lisbon to Cascais. they lost some 500 dead along the way.[76]

On 6 June the Count of Fuentes marshalled an army in Lisbon to march on Cascais so as to inflict as many casualties as possible. They spent the night in Oeiras.[77] When they reached the English trenches on the morning of 7 June they were met with cannon fire from Drake's fleet. A council of war decided that it was impracticable to launch any sort of direct assault on the English. On the way back to Lisbon, Fuentes stopped off at the castle of São Julião to consult with Bazán.[78] They arranged to keep the enemy isolated to Cascais, essentially besieging them.

During the morning of 8 June, the Earl of Essex, champing at the bit to achieve glory and angry with the lack of success of the slow spineless army, arranged to have a trumpeter bring to the Spanish a message challenging them to open combat. The message read:

We, the Generals Drake and Norris and Earls of [such and such], having been informed that the Count of Fuentes, General of the Kingdom of Portugal, and others on his side, have said that we retreated and fled in secret from Lisbon, and not in the manner of an army intending to fight, hereby state that we have not fled. So that it may be known by our deeds that we are ready and willing, we are sending you this trumpeter with our challenge, and inform you that we await you on this field of Oeiras to offer battle until the end of the day.

— Relación de lo subçedido del [sic] armada enemiga del reyno de Ynglaterra a este de Portugal con la retirada a su tierra este año de 1589, Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, mss 18579 (in Spanish), p. 79

The messenger was shown all courtesies in accordance with the rules of hospitality then sent back with the message being unopened.[79] Shortly thereafter, The most important Portuguese aristocrat Dom Teodósio II, 7th Duke of Bragança arrived in Lisbon with 20 noblemen including his brother Dom Duarte of Bragança, Marquis of Frechilla, his personal guard of 70 halberdiers, 200 lancers and 1,000 infantrymen.[80] His arrival not only brought reinforcements to defend Lisbon, it also solidified the Catholic union while leaving Dom António looking like little more than a fugitive from justice.

While Drake was anchored in Cascais, he seized several wheat-laden urcas giving him a veritable inexhaustible supply source. They engaged the nearby mills to grind the wheat into flour from which bread was made. On 9 June, Fuentes sent Captain Francisco de Velasco with a small division of infantry and cavalry to destroy those mills thus eliminating the usefulness of the vast amounts of wheat for making bread. They resorted to boiling the wheat in order to eat it.[81] On 10 June, Francisco Coloma inventoried the enemy's vessels anchored at Cascais as counting 147. In reporting that, he added that, though they continue to threaten to attack the entrance of the estuary, he didn't believe they actually would do so for during the past few days, they had the most optimal weather and tides to do so if they wished to.[82] Then, on 11 June. Captain Francisco de Cárdenas, commander of the castle of Cascais, received a visit from two Franciscan monks from the monastery of São António solemnly vowing that Lisbon had surrendered to Dom António three days earlier and it would be a mortal sin to keep fighting when all hope was lost. Several days prior, Cárdenas had sent two soldiers to request more men and ammunition from Lisbon who were never heard from, nor had he any news from Lisbon, so he had no reason to doubt the monks' claims. He surrendered the castle without a fight, obtaining honourable terms, leaving with ~50 men, banners and weapons, and even given a ship to sail to Setúbal. Within the castle were plenty of supplies and ammunition, and 14 cannons. Upon his arrival in Setúbal, Cárdenas was arrested then beheaded.[83]

As each day passed, the Spanish-Portuguese, a.k.a. Iberian army was growing stronger while the English were dwindling. Observing the odd passive conduct of the enemy fleet, Lisbon still thought the English would return to launch a combined ground and sea attack on 13 June, St. Anthony's feast day, the city's own patron saint. The Count of Villadorta, general of the Portuguese cavalry, had stationed a strong detachment near Cascais and the next day, the Duke of Bragança joined his forces to complete the siege by land. Meanwhile, the Adelantado of Castile, Martín Padilla, arrived in São Julião with 15 well equipped galleys to reinforce those of Bazán thus completing the siege by sea.[84] The English finished embarking that very night.

Out to sea

[edit]

Everything was ready on 16 June to launch a major offensive against the English assuming the weather cooperated, which it didn't, so the attack was delayed. Also that day, two small vessels arrived from England bringing correspondences from the Queen dated 20 May o.s. and news that 17 supply vessels, but no troops, were en route;[85] Most of those ships had earlier abandoned the fleet.[86]T hose supply ships arrived on 17 or 18 June, commanded by Captain Cross.[87] In her letters, the queen ordered the immediate return of her favourite Essex and vehemently criticized Drake and Norris for how badly they've conducted the expedition thus far, especially for not going to Santander to destroy the remnants of the Spanish Armada despite the favourable winds to do so. All Drake could think of was leaving Portugal as quickly as possible to achieve some sort of victory but the wind wasn't cooperating. It didn't cooperate on 17 June either. In the several days that the English Armada was anchored off Cascais, Drake had collected numerous merchantmen and the day before they sailed, a fleet of 20 French and 60 Hanseatic ships was captured in the mouth of the Tagus. That seizure, notes R. B. Wernham, "dealt a useful blow to Spanish preparations",[88] but later required a publicly printed justification from the Queen's own printer on 30 June 1589 o.s., since, without booty, she and her fellow English investors faced considerable losses.[89]

On the morning of 18 June, despite the unfavourable wind, Drake finally decided to set sail away from the coast with his fleet and the captured merchantmen totalling some 210 ships[90] which is when Essex escorted some 30 Dutch merchant ships which were discharged thus ending their participation in the expedition.[91]So as to placate his queen, Drake decided to try and capture the treasure fleet in the Azores but not being able to sail west, the winds pushed him south-southwest, staying within sight of the Portuguese coast. Meanwhile, the Iberian troops who arrived in Cascais after the English departure found it in utter shambles. Part of the castle had been blown up, the entire town sacked, and the churches desecrated. It was so dirty and dilapidated that Fuentes ordered the garrison to billet in adjacent towns until it had been cleaned up.[92]

The Adelantado set off on pursuit of the English Armada with 9 galleys on 19 June, while in Lisbon 15 caravels with extra men and munitions were being made ready to reinforce the Azores. The first engagement at sea was on the morning of 20 June resulting in the loss of 9-11 English ships, two smaller boats and the dispersion of the fleet.[93][94] By the end of the day, Drake had managed to reassemble much of his fleet. Young William Fenner who had come with the 17 supply ships commanded by Captain Cross was separated further after a storm during the night and found himself heading toward the archipelago of Madeira, ultimately anchoring in Porto Santo where, the next day, seven more English vessels joined him. They took the island and resupplied themselves over the next two days. Unable to find the rest of the fleet, they set sail for England.[87]

The English prisoners captured by the Iberians following the 20 June battle revealed that the fleet had no provisions making an adventure to the Azores unlikely so the Iberians shifted their attention to the 500 man garrison Norris left at Peniche on 28 May. Drake made his way up the Portuguese coast against the wind to retrieve those men while Guzmán and Bravo rushed thereto with their cavalry. The latter arrived on 22 June making a surprise attack just as the garrison started to embark on a small ship, killing or capturing some 300.[93] Tacking his way north along the Portuguese coast, Drake arrived at Peniche the next day hoping to pickup the garrison only to be met with cannon fire from the fortress. He sailed off and on the next day, 24 June, a favourable northeast wind came up and Drake set off for the open sea, seemingly heading for the Azores.

Raid on Vigo

[edit]Drake struggled against the wind, tacking his way to Vigo over the next five days, tossing the dead overboard by the hundred, finally arriving within sight of the undefended small fishing town on the morning of 29 June.[95] By nightfall, about 133 ships had anchored off Bouzas, Vigo and Teis with 20 vessels guarding the area around the Cíes Islands.[96] Since it was too late in the day to start a landing, they waited until the next morning which gave the Spaniards time to evacuate the town. Their strategy was essentially to divide and conquer. They expected the English to enter the town as a cohesive groups but, after seeing the town empty of people and valuables, they would eventually spread out across the outskirts where ambushes were waiting for them. Come dawn, 30 June, the English came ashore at three different locations with about 2,000 men and were, at once, stunned and disappointed to find the town completely deserted. Incensed by their defeats in Coruña and Lisbon, they showed no mercy to Vigo. Destruction started with the armada's cannons followed by iconoclasm and burning of churches then setting the rest of the town ablaze. Surrendering to their desires for wanton destruction gave them a dangerous sense of confidence that allowed their greed to take over and sent them to disperse in search of food, loot, etc.[97] There were a few skirmishes that day a few hundred invaders were killed but the main purpose of the landing was to refill their water casks which went on during the chaos.

The next day, 1 July, Don Luis Sarmiento showed up with a sizable Spanish force, catching the English unawares, killing hundreds and capturing prisoners. Drake quickly ordered his men to reembark then sent a dispatch promising to leave the estuary without causing further harm on condition the prisoners were returned. When the Spanish commander saw the totality of the devastation, he had the prisoners hanged within view of the fleet and challenged Drake to send more Englishmen so he could hang them all.[98] The next morning, Drake sailed out of the estuary with most of the fleet leaving Norris behind with some 30 vessels as he was further up the waterway and couldn't make it out before a storm hit. Two of Drake's ships were captured that day, one ran aground and two more were smashed against the rocks near Cangus. On 3 July, Drake still struggled against the wind on his way to Finisterre while Norris, still anchored off Cíes Islands had the artillery removed from the ship that ran aground then set it ablaze. The latter was able to leave Cíes on 4 July.[99]

Return to England

[edit]Spain saw the last of the English fleet on 5 July as it struggled against the wind past Finisterre. Captain Diego de Aramburu was dispatched from Santander with a flotilla of zabras to chase the English fleet nearly back to its home shores.[100]

From this point on, it becomes difficult to follow the path of the armada since information is available for only a small number of vessels, but what there is, is shockingly grim. Thomas Fenner's 500 ton Dreadnought set off with nearly 300 sailors then returned to Plymouth with only 18 fit to do work, the rest were dead or ill, including Fenner.[101] Of the crew of the Griffin of Lübeck, only 5 or 6 men were well but too weak to hoist the sails, the rest were dead, including the captain, or diseased, and of the 50 soldiers that were aboard, 32 or 33 had to be cast overboard. Two more died just as they landed in Sandwich.[102] Drake's flagship, the Revenge had sprung a leak from storm damage and almost foundered as she led the remainder of the fleet home to Plymouth where she docked on 10 July.

Aftermath

[edit]Norris landed in Plymouth on 13 July and immediately conspired with the Earl of Essex and Anthony Ashley to cover up the extent of the disaster and even go so far as to try and spin it into a triumph.[103] The next day, Norris sent a letter to Walsingham admitting failure and drawing the latter into the conspiracy thus making him a coconspirator.[104][103] On 17 July a reply to the falsified reports arrived from Elizabeth expressing her delight with the "happy success" of the expedition.[105][106] Following Norris' initial report, a cascade of propaganda erupted immediately with the most detailed account (in English), written in the form of a letter by an "anonymous" participant, published in 1589: A true Coppie of a Discourse written by a Gentleman, employed in the late Voyage of Spain and Portingale...,[107] which unabashedly set out to restore the credit of the participants but it could not conjure away "the utter failure of the campaign or the conduct of the men who took part in it."[108] Hume later noted, "…they wrote from Cascaes (Cascais) a full account of all that had happened in the best light they could devise…"[109] However, the English narrative has been shown to have been a highly-effective means to suppress the magnitude of the disaster.[7] Rarely in the history of England had the government, or the crown, been so badly informed.[105]

An unintended consequence of this misinformation campaign was the rapid spread of disease carried by the fleet personnel from the returning vessels onto the port town populations in England. Since the Queen's subjects were told the expedition was a success, the returning ships docked without being checked out.[110] In Plymouth alone, there were 400 local towns people dead within the first few weeks.[111] Lord Burleigh issued a proclamation that access to London by expedition participants was prohibited on penalty of death.[112][113]

None of the campaign's objectives had been accomplished, and for a number of years, the expedition's results discouraged further joint stock adventures on such a scale.[31][114] The English expeditionary force had sustained a heavy loss of ships, troops and resources yet had not inflicted decisive damage on the Spanish forces. As it was a joint stock expedition it was a financial failure too, having only brought back 150 captured cannon and £30,000 of plunder.[31] The financial problems were ultimately settled by simply not paying the survivors.[110] Following a thorough investigation of the expedition, Drake and Norris were never publicly admonished.[115] Still, they both fell out of favour, with Norris not being given another command until 1591 and Drake waiting until 1595 to finally embark on his next, and final voyage.[116][117] Despite all this, the queen never amended her triumphalist letter of 7 July 1589 o.s..

Despite 25 vessels with 3,000 men that abandoned the expedition and ended up in England and La Rochelle, 17 had returned and rejoined the expedition,[87] thus, as many as 40 ships of the English fleet were sunk, scuttled, captured or otherwise unaccounted for[10] at Coruña, Lisbon and during the English retreat.[6][7] Fourteen of the ships were lost directly to the actions of Spanish naval forces: three at Coruña; six were sunk by the galleys led by Padilla and three seized by another galley's squadron commanded by Admiral Alonso de Bazán, all of them off Lisbon; two others were captured in the Bay of Biscay by the flotilla of zabras from Santander under Captain Diego de Aramburu, on their way back to England.[94][100] A 2021 environmental study carried out by the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture at Coruña harbour claims to have found the remains of five English ships from Drake's fleet at the O Burgo estuary.[118] The rest were lost to a stormy sea as the fleet made its return voyage, checked and harassed by Aramburu's zabras as far as the English channel.[119] According to contemporary historian Fray Juan de Vitoria, the Spanish flotilla rounded up a good number of castaways during the pursuit.[120] Some of the English vessels arrived in Britain badly undercrewed, their complements being depleted by famine and disease.[88]

The scope of the tragedy and the widely varying accounts makes it next to impossible to give an accurate number of men and ships lost in this expedition. What has been documented is of the 3,722 men who returned and demanded their pay, only 1,042 received pay and of the thousands of widows, only 119 received their husband's pay.[6] Using the data Wernham compiled, assuming 27,667 men set out, if only 3,722 came back, that would mean nearly 24,000 died, deserted, or are otherwise unaccounted for. Various contemporary chroniclers reported deaths ranged everywhere from 11,000[5] to more than 18,000,[121] in contrast, the number of survivors were reported to range from 3,000[122] to 5,000.[109] The chimerical "anonymous" discourse, actually written by Wingfield, claims more than 6,000 returned out of the 13,500 who embarked.[123] Even if the more commonly accepted number of 23,375 men embarking with 5,000 surviving, that's still more than 18,000 dead.

Determining the number of ships lost is no less problematic. Starting with the 180 documented ships and adding others in the days after the final recorded inventory, 200 cannot be considered exaggerated. We find that 102 ships were named on the 5 September 1589 o.s. pay list. Of the 84 ships on the 9 April o.s. list that set sail, only 69 appear on the 5 September o.s. list, thus, according to Wernham, 15 ships were lost. But the number of those not listed and failed to return is unknown. In addition to the 69 that are known to have sailed and returned, another 33 returned with them; most of them medium-sized.[124]

Regardless, with the opportunity to strike a decisive blow against the weakened Spanish Navy lost, Philip was able revive his navy the very next year, sending 37 ships with 6,420 men to Brittany where they established a base of operations on the Blavet river.[125] The English and Dutch ultimately failed to disrupt the various fleets of the Indies despite the great number of military personnel mobilized every year. Thus, Spain remained the predominant power in Europe for several decades.[2] The failure of the expedition depleted the financial resources of England's treasury, which had been carefully restored during the long reign of Elizabeth I, and the expedition's failure was so embarrassing that England continues to downplay its significance.[126] The war was financially costly to both of its protagonists, and the Spanish Empire, which was fighting France and the United Provinces at the same time, would be compelled in financial distress to default on its debt repayments in 1596 after the English Capture of Cádiz. After a successful raid on Cornwall in 1595,[127] three more armadas were sent by Spain: in 1596 (126-140 ships) which was scattered by a storm, 1597 (140 ships) where 7 ships managed to land 700 elite forces on a beach in one of the creeks off the Helford River near Falmouth, and 1601 (33 ships) where the Spanish held the town of Kinsale for three months, but these efforts ultimately failed to succeed.[128]

Peace was finally agreed at the signing of the Treaty of London in 1604.

Legacy

[edit]The failure of the English Armada is barely acknowledged by the British historiography, as explained by David Keys:

The English Armada was larger than the Spanish, and from many points of view it was an even greater disaster. This fact, however, is completely overlooked. It is never mentioned in the history courses taught in British schools and a majority of British history teachers have never even heard of it.

— Gran Bretaña olvida su gran desastre naval mientras recupera restos de la Armada Invencible (in Spanish: "Britain forgets its great naval disaster as it recovers wreckage of the Invincible Armada"), ABC, 6 August 2001, p. 38

Nevertheless, even the "landmark" 11th Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica (1911) does mention, if only in passing, that "the attempt on Portugal in 1589 under Drake and Norris proved a complete failure."[129]

In Portugal, the pillages some of the English soldiers committed along the way, along with the ultimate ineffectiveness of the forces sent by England, gave rise to the saying "friend from Peniche", meaning someone who falsely appears to be a friend.[130] "Amigo de Peniche" is also a type of local pastry made of flour, eggs, sugar and almonds.[131]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Philip's spies in England reported losses exceeding 18,000 men. No French or Italian report put the number at lower than 15,000 dead.[7]

- ^ Throughout the Catholic world, the Gregorian calendar replaced the Julian calendar in October 1582 which corrected a 10-day error. England didn't adopt it until 1752 so all English State papers have Julian dates. Dates on original English source documents will be indicated herein with the suffix "o.s." for old style.

References

[edit]- ^ Martins 2014, p. 442.

- ^ a b Elliott 1982, p. 333.

- ^ Morris 2002, p. 335.

- ^ a b c d e Wernham 1988, p. 346.

- ^ a b Bucholz & Key 2009, p. 145.

- ^ a b c d e Wernham 1988, p. 341.

- ^ a b c d e Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 245.

- ^ Hampden 1972, p. 254.

- ^ Fernández Duro, Cesáreo (1972). Armada Española desde la unión de los Reinos de Castilla y Aragón (PDF) (in Spanish). Vol. III. Museo Naval de Madrid, Instituto de Historia y Cultura Naval. p. 51.

- ^ a b Fernández Duro 1972, p. 51.

- ^ Bicheno 2012, p. 266.

- ^ Elliott 1982, p. 351.

- ^ Hume, Martin (1896). The Year After the Armada: And Other Historical Studies. London: T F Unwin. p. 23.

- ^ a b c Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 36.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d Rodríguez González, Agustín Ramón (2006).Victorias por mar de los españoles. Madrid: Biblioteca de Historia, Grafite Ediciones, pp. 60–62

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 37.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Wernham 1988, pp. 36–38.

- ^ Wernham 1988, pp. 338–41.

- ^ Wernham 1988, p. 297.

- ^ Hume 1896, p. 26.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Hume 1896, p. 28.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 120–21.

- ^ Rodriguez-Salgado & Adams 1991, p. 116.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 39.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 51.

- ^ Rodríguez González 2006, pp. 60–64.

- ^ Hume 1896, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d e R. B. Wernham (1951b), "Part II" The English Historical Review 66.259 (April 1951), pp. 194–218, especially 204–214. Wernham's articles are based on his work editing Calendar State Papers Foreign: eliz. xxiii (January–June 1589).

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 43–51.

- ^ Valcárcel 2004, pp. 51–63.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 77–97.

- ^ Motley, John Lothrop (1867). History of the United Netherlands: 1586-89. Harper & Brothers. p. 555. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ Graham 1972, p. 178.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 103–07.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 112.

- ^ "O ataque de Drake á Coruña... que é lenda e que é realidade?". Historia de Galicia (in Galician). 28 February 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Report from Lisbon, 20 May 1589, Archivo General de Simancas (AGS). Guerra antigua (in Spanish). file 248, № 135.

- ^ Wernham 1988, p. 231.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 122.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 125.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 126.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 126–27.

- ^ Hume 1896, p. 43.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 130.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 128–29.

- ^ Hume 1896, p. 46.

- ^ Hume 1896, p. 51.

- ^ Wernham 1988, p. 267.

- ^ Relación de lo subçedido del [sic] armada enemiga del reyno de Ynglaterra a este de Portugal con la retirada a su tierra este año de 1589, Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, mss 18579 (in Spanish), pp. 40-41

- ^ Memoria de Vinda dos Ingleses a Portugal em 1589, p. 258, quoted in Pires de Lima, Durval, O ataque dos ingleses a Lisboa em 1589 contado por uma testemunha in Lisboa e seu Termo: Estudios e Documentos, Associação doa Arqueólogos Portugueses (in Portuguese), vol. 1, Lisbon, 1948.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 137.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 139–40.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 143.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 147–50.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 153–55.

- ^ Wernham 1988, p. xlviii.

- ^ Relación de lo subçedido del [sic] armada enemiga del reyno de Ynglaterra a este de Portugal con la retirada a su tierra este año de 1589, Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, mss 18579 (in Spanish), pp. 51-52.

- ^ Memoria de Vinda dos Ingleses a Portugal em 1589, p. 262, quoted in Pires de Lima, Durval, O ataque dos ingleses a Lisboa em 1589 contado por uma testemunha in Lisboa e seu Termo: Estudios e Documentos, Associação doa Arqueólogos Portugueses (in Portuguese), vol. 1, Lisbon, 1948.

- ^ Relación de lo subçedido del [sic] armada enemiga del reyno de Ynglaterra a este de Portugal con la retirada a su tierra este año de 1589, Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, mss 18579 (in Spanish), p. 61.

- ^ Wernham 1988, pp. xlviii–xlix.

- ^ a b Hume 1896, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 167–68.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 168–69.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 171.

- ^ Hume 1896, p. 62.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 180.

- ^ Wernham 1988, pp. xlviii–lii.

- ^ Memoria de Vinda dos Ingleses a Portugal em 1589, pp. 277-278, quoted in Pires de Lima, Durval, O ataque dos ingleses a Lisboa em 1589 contado por uma testemunha in Lisboa e seu Termo: Estudios e Documentos, Associação doa Arqueólogos Portugueses (in Portuguese), vol. 1, Lisbon, 1948.

- ^ Relación de lo subçedido del [sic] armada enemiga del reyno de Ynglaterra a este de Portugal con la retirada a su tierra este año de 1589, Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, mss 18579 (in Spanish), p. 68.

- ^ Letter from Francisco de Coloma, Archivo General de Simancas (AGS). Guerra antigua (in Spanish). file 249, № 129.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 184.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 185–86.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 192.

- ^ Relación de lo subçedido del [sic] armada enemiga del reyno de Ynglaterra a este de Portugal con la retirada a su tierra este año de 1589, Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, mss 18579 (in Spanish), p. 76.

- ^ Relación de lo subçedido del [sic] armada enemiga del reyno de Ynglaterra a este de Portugal con la retirada a su tierra este año de 1589, Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, mss 18579 (in Spanish), p. 78.

- ^ Hume 1896, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Relación de lo subçedido del [sic] armada enemiga del reyno de Ynglaterra a este de Portugal con la retirada a su tierra este año de 1589, Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, mss 18579 (in Spanish), p. 79.

- ^ Relación de lo subçedido del [sic] armada enemiga del reyno de Ynglaterra a este de Portugal con la retirada a su tierra este año de 1589, Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid, mss 18579 (in Spanish), p. 80.

- ^ Francisco Coloma to the King, entrance to Lisbon Estuary, 10 June 1589, Archivo General de Simancas (AGS). Guerra antigua (in Spanish). file 249, № 121.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 202–03.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 206–07.

- ^ Wernham 1988, p. 164.

- ^ Wernham 1988, p. 173.

- ^ a b c Wernham 1988, p. 240.

- ^ a b Wernham, R B (January 1951). Queen Elizabeth and the Portugal Expedition of 1589: Part II (66 ed.). The English Historical Review. pp. 194–218.

especially 204–214. Wernham's articles are based on his work editing Calendar State Papers Foreign: eliz. xxiii (January–June 1589)

- ^ England and Wales. Sovereign (1558-1603 : Elizabeth I); Beale, Robert; Penrose, Boies; Penrose, Boies; Lyell, James P. R. (James Patrick Ronaldson) (1589). A declaration of the cavses, which mooved the chiefe commanders of the nauie of Her Most Excellent Maiestie the Queene of England, in their voyage and expedition for Portingal, : to take and arrest in the mouth of the river of Lisbone, certaine shippes of corne and other prouisions of warre bound for the said citie : prepared for the seruices of the King of Spaine, in the ports and prouinces within and about the sownde, the 30. day of Iune, in the yeere of Our Lord 1589. and of Her Maiesties raigne the one and thirtie. Boston Public Library. London : Imprinted by the deputies of Christopher Barker, printer to the Queenes Most Excellent Maiestie.

- ^ Wernham 1988, p. 234.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 212.

- ^ The Count of Fuentes to the King, Lisbon, 26 June 1589, Archivo General de Simancas (AGS). Guerra antigua (in Spanish). file 249, № 136.

- ^ a b Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 219.

- ^ a b González, Rodríguez; Ramón, Agustín (19 September 2002). "Una derrota de Drake ante Lisboa". Circulo Naval Español (in Spanish).

- ^ Hume 1896, p. 70.

- ^ Report by Juan Rodríguez, captain of the ship called La Trinidad, Archivo General de Simancas (AGS). Guerra antigua (in Spanish). file. 250, № 154.

- ^ Santigo y Gómez, José, Historia de Vigo y su comarca, Madrid: Impr. del Asilo de Huérfabism, 1919, pp. 328-330.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 233.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 235–36.

- ^ a b Gonzalez-Arnao Conde-Luque 1995, p. 94.

- ^ Wernham 1988, p. lxv.

- ^ Wernham 1988, p. 211.

- ^ a b Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 241.

- ^ Wernham 1988, pp. 199–200.

- ^ a b Wernham 1988, p. lvi.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 243.

- ^ Wingfield, Anthony (1589). "A True Coppie of a Discourse written by a Gentleman employed in the late Voyage of Spaine and Portingale". Internet Archive. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ Hume 1896, p. 11.

- ^ a b Hume 1896, p. 68.

- ^ a b Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 244.

- ^ Wernham 1988, p. 241.

- ^ Gonzalez-Arnao Conde-Luque 1995, p. 96.

- ^ Rebello Da Silva, Luis Augusto (1858). Quadro elementar das relações politicas e diplomaticas de Portugal (in Portuguese). Lisbon: Pariz, J. P. Aillaud. p. 218.

- ^ Wagner 1999, p. 242.

- ^ Sugden, John (1990). Sir Francis Drake. H. Holt. p. 283. ISBN 0805014896.

- ^ "The Last Voyage of Sir Francis Drake". loc.gov. p. 588. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Wernham 1988.

- ^ Olaya, Vicente G. (24 February 2021). "Francis Drake's lost fleet emerges in northwestern Spain". EL PAÍS English Edition. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ Gómez, José de Santiago y (1896). Historia de Vigo y su comarca (in Spanish). Impr. del Asilo de Huérfanos. p. 333.

- ^ Fernández Duro 1972, p. 52.

- ^ Hume, Martin A S (1899). "Simancas: July 1589". Calendar of State Papers, Spain (Simancas). 4 (1587–1603). London: 549. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ As told by two ensigns held prisoner in Corunna, Archivo General de Simancas (AGS). Guerra antigua (in Spanish). file 250, № 348.

- ^ Wingfield, Anthony (1589). "A True Coppie of a Discourse written by a Gentleman employed in the late Voyage of Spaine and Portingale". Internet Archive. p. 10. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2020, pp. 246–48.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, p. 253.

- ^ Gorrochategui Santos 2018, pp. 3–4, and pp. 245-246.

- ^ Cruickshank, Dan (2001). Invasion: Defending Britain from Attack. Boxtree. pp. 58–62. ISBN 9780752220291.

- ^ Tenace, E. (2003), "A Strategy of Reactions: The Armadas of 1596 and 1597 and the Spanish Struggle for European Hegemony." English Historical Review, 118, pp. 855–882

- ^ Pollard, Albert Frederick (1911). "English History". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "AMIGOS DE PENICHE – UMA PARTIDA DA HISTÓRIA - Município de Peniche - Capital da Onda". 5 March 2016. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ "Amigos de Peniche é lenda que inspira doçaria regional". Pastelarias Roma (in European Portuguese). 22 June 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bicheno, Hugh. (2012). Elizabeth's Sea Dogs: How England's Mariners Became the Scourge of the Seas. Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-174-3.

- Bucholz, R O; Key, Newton (2009). Early modern England 1485–1714: a narrative history. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-1405162753.

- Elliott, J H (1982). Europe Divided (1559–1598). Cornell University Press. ISBN 9788484326694.

- Gonzalez-Arnao Conde-Luque, Mariano (1995). Derrota y muerte de Sir Francis Drake, a Coruña 1589 – Portobelo 1596 (in Spanish). Xunta de Galicia, Servicio Central de Publicacións. ISBN 978-8445314630.

- Gorrochategui Santos, Luis (2018). English Armada: The Greatest Naval Disaster in English History. Oxford: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1350016996.

- Hampden, John (1972). Francis Drake, privateer: contemporary narratives and documents. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780817357030.

- Morris, Terence Alan (2002). Europe and England in the sixteenth century. Routledge. ISBN 9781134748204.

- Graham, Winston (1972). The Spanish Armadas. Collins. ISBN 9780002218429.

- Martins, Oliveira (2014). História de Portugal (in Portuguese). Ediçoes Vercial. ISBN 978-9898392602.

- Rodríguez González, Agustín Ramón (2006). Victorias por mar de los españoles (in Spanish). Madrid: Biblioteca de Historia, Grafite Ediciones. ISBN 849-6281388.

- Rodriguez-Salgado, M J; Adams, Simon (1991). England, Spain and the Gran Armada, 1585-1604. Barnes & Noble. ISBN 0389209554.

- Wagner, John A (1999). Historical Dictionary of the Elizabethan World: Britain, Ireland, Europe, and America. New York: Checkmark Books. ISBN 9781573562003.

- Wernham, R B (1988). The Expedition of Sir John Norris and Sir Francis Drake to Spain and Portugal, 1589. Aldershot: Navy Records Society. ISBN 9781911423560.

- Valcárcel, Isabel (2004). Mujeres de armas tomar (in Spanish). Edaf Antilla. ISBN 9788496107564.

Further reading

[edit]- Gorrochategui Santos, Luis (2020). Contra Armada: La mayor victoria de España sobre Inglaterra (in Spanish). Editorial Crítica. ISBN 978-8491992301.

- Mattingly, Garrett, The Armada (Mariner Books, New York 2005). ISBN 0618565914

- Parker, Geoffrey (1996). "The Dreadnought Revolution of Tudor England". The Mariner's Mirror. 82 (3): 269–300. doi:10.1080/00253359.1996.10656603.

- J. H. Parry, 'Colonial Development and International Rivalries Outside Europe, 1: America', in R. B. Wernham (ed.), The New Cambridge Modern History, Vol. III: 'The Counter-Reformation and Price Revolution 1559–1610' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971): 507–531.

- Helmut Pemsel, Atlas of Naval Warfare: An Atlas and Chronology of Conflict at Sea from Earliest Times to the Present Day, translated by D. G. Smith (London: Arms and Armour Press, 1977).

- R. B. Wernham (1951a), "Queen Elizabeth and the Portugal Expedition of 1589: Part I" The English Historical Review 66.258 (January 1951), pp. 1–26

External links

[edit]- The Year After the Armada, and other historical studies, Martin Andrew Sharp Hume (New York 1896)

- Library of Congress: Hans P. Kraus, "Sir Francis Drake: A Pictorial Biography": "The Beginning of the End: The Drake-Norris Expedition, 1589" From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

- Conflicts in 1589

- Military history of Spain

- Military history of Portugal

- History of the Royal Navy

- Maritime history of England

- Tudor England

- Naval battles of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604)

- 1589 in Europe

- Francis Drake

- 1589 in England

- 1589 in the Spanish Empire

- Invasions of Spain

- Invasions of Portugal

- Invasions by England