Pál Teleki

Pál Teleki | |

|---|---|

Teleki as prime minister | |

| Prime Minister of Hungary | |

| In office 16 February 1939 – 3 April 1941 | |

| Regent | Miklós Horthy |

| Preceded by | Béla Imrédy |

| Succeeded by | László Bárdossy |

| In office 19 July 1920 – 14 April 1921 | |

| Regent | Miklós Horthy |

| Preceded by | Sándor Simonyi-Semadam |

| Succeeded by | István Bethlen |

| Minister of Religion and Education | |

| In office 14 May 1938 – 16 February 1939 | |

| Prime Minister | Béla Imrédy |

| Preceded by | Bálint Hóman |

| Succeeded by | Bálint Hóman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 November 1879 Budapest, Hungary |

| Died | 3 April 1941 (aged 61) Budapest, Hungary |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse | Countess Johanna von Bissingen-Nippenburg |

| Children | 2, including Géza Teleki |

| Signature | |

Count Pál János Ede Teleki de Szék (1 November 1879 – 3 April 1941) was a Hungarian politician who served as Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Hungary from 1920 to 1921 and from 1939 to 1941. He was also an expert in geography, a university professor, a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and chief scout of the Hungarian Scout Association. He descended from an aristocratic family from Transylvania.

Teleki tried to keep Hungary neutral during the early stages of the Second World War despite cooperating with Nazi Germany to regain Hungarian territory lost in the Treaty of Trianon. When Teleki learned that German troops had entered Hungary en route to invade Yugoslavia, effectively killing hopes of Hungarian neutrality, he committed suicide.

He is a controversial figure in Hungarian history because as prime minister he tried to preserve Hungarian autonomy under difficult political circumstances, but also proposed and enacted far-reaching anti-Jewish laws.[1][2]

Early life

[edit]

Teleki was born to Géza Teleki (1844–1913), a Hungarian politician and Interior Minister, and his wife Irén Muráty (Muratisz) (1852–1941), the only child of a very wealthy Greek merchant and banking family, in Budapest, Hungary.[7] Irén Muráty was fluent in Greek.[8] Her family, the Muráty (Greek: Μουράτη), originally came from Kozani, in northern Greece.[8] Teleki attended Budapest Lutheran elementary school from 1885 to 1889, and Pest Calasanz High School ("gymnazium") from 1889 to 1897. In 1897 he started upper-division work at Budapest University studying law and political science. Teleki then studied at the Royal Hungarian Academy of Economy in Magyaróvár (Magyaróvári Magyar Királyi Gazdasági Akadémia), and after struggling to complete his studies, graduated with a PhD in 1903. He went on to become a university professor and expert on geography and socio-economic affairs in pre-World War I Hungary and a well-respected educator. For instance, Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn was one of his students. He fought in the First World War as a volunteer.

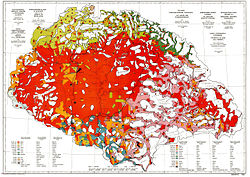

In 1918–19,[9] he compiled and published a map depicting the ethnographic make up of the Hungarian nation. Based on the density of population according to the 1910 census, the so-called Red map was created for the peace talk in Treaty of Trianon. His maps were an excellent composition of social and geographic data, even by today's well-developed Geographic Information System's point of view. From 1911 to 1913 he was Director of Scientific Publishing for the Institute of Geography, and from 1910 to 1923 he was Secretary General of the Geographical Society. He was a delegate to the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919.[10] Between 1937 and 1939, he was the Hungarian representative in the International committee on intellectual cooperation of the League of Nations.[11]

Scouting

[edit]In the summer of 1927, Teleki's son Géza, a member of the Hungarian Sea Scouts, was attending a Sea Scout rally held at Helsingør, Denmark. On a sailing cruise, he ignored a reprimand from his Scoutmaster, Fritz M. de Molnár, for failure to carry out a small but necessary exercise of seamanship. Molnár tried to drive home his point by threatening to tell the boy's father on their return to Budapest. Géza replied "Oh, Dad's not interested in Scouting." This roused Molnár's mettle, and he determined to take up the subject of Scouting with Count Teleki.[12]

Molnár's talk about Scouting intrigued Teleki, and he was instrumental in supporting Scouting within Hungary. He became Hungary's Chief Scout, a member of the International Scout Committee from 1929 until 1939, Camp Chief of the 4th World Scout Jamboree held at The Royal Forest at Gödöllő, Hungary, Chief Scout of the Hungarian Scout Association, and a close friend and contemporary of Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell. His influence and inspiration were a major factor in the success of Scouting in Hungary, and contributed to its success in other countries as well.[13]

Political life

[edit]1905-1920

[edit]He first ran in the 1905 elections under the banner of the National Constitutional Party, formed from the "dissidents" of the Liberal Party led by junior Gyula Andrássy, in the electoral district of Nagysomkút in Szatmár County. He was elected as a member of parliament. He secured his mandate again in the 1906 elections. However, by the 1910 elections, when the collapse of the coalition government became evident, he chose not to pursue another mandate and temporarily withdrew from politics. At that time, he was not yet a significant political figure. He served as a volunteer in World War I, fighting first on the Serbian front and then on the Italian front, where he held the rank of captain until 1917. He was subsequently appointed head of the National War Relief Office.

After the victory of the Aster Revolution, he retreated from public life and stayed in Switzerland during the period of the Hungarian Soviet Republic. Meanwhile, at the request of the Anti-Bolshevik Committee, he served as foreign minister in the counter-revolutionary governments in Szeged (all three of them).

In the first elections following the victory of the counter-revolution in 1920, he won a parliamentary mandate in the city center district of Szeged representing the Christian National Union Party. In the government formed on March 15 by Simonyi-Semadam, he was appointed foreign minister, a position he accepted on April 19. He attended the signing of the Treaty of Trianon in this capacity, although the actual signing was carried out by two other politically insignificant members of the Hungarian delegation. The government resigned a month later, and Horthy requested Teleki to form a new cabinet, which he accepted.

First premiership

[edit]On July 25, 1920, Miklós Horthy was appointed Teleki as Prime Minister. Additionally, he served as the minister without portfolio for national minorities and led the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Following King Charles IV's attempt to return, he resigned from the premiership on April 14, 1921.

One of the most controversial issues during Teleki's first administration was the numerus clausus law, specifically the 1920 Act XXV ('regulating enrollment in universities, the technical university, the Budapest University of Economics, and law academies'), which means 'closed number' (i.e., a defined, fixed number). It was introduced to Parliament by the Minister of Religion and Public Education and was adopted in September 1920. The law aimed primarily to adjust the number of students in Hungarian higher education to the perceived or actual needs of the country, intending to limit the number of those entering higher education. The proportion of students was meant to reflect the ratio of the 'ethnic groups' living in Hungary. The main objective of the law was to ensure that 'Hungarians' (excluding Jewish Hungarians) participated in universities in proportion to their numbers within the population. The law provoked deep outrage among Jewish communities in Hungary as it questioned their Hungarian identity. Many regarded the law as the first anti-Jewish law, as it primarily restricted the Jewish community, treating them as a separate nationality rather than by their religious denomination, which deviated from previous legal practices, effectively categorizing them as non-Hungarians.

Party Leader

[edit]In 1938, Teleki regained a parliamentary mandate in a by-election in the Tokaj district, resigning from his membership in the upper house to rejoin the House of Representatives. On May 14, 1938, he became the Minister of Religion and Public Education in the newly formed Imrédy government, a position he held until Imrédy's downfall. He was one of the leading members of the Hungarian delegation during the negotiations of the First Vienna Award. In contrast to the Imrédy government, which turned toward Germany and Italy, the Axis Powers, he was a staunch Anglophile.

On February 2, 1939, as a solution to the parliamentary conflict (after 62 government party representatives had previously split and turned against Imrédy), under Teleki's leadership, the government party and the former 'dissident' representatives reunited, and the government party adopted the name Hungarian Life Party (previously known as the National Unity Party).

Preserved Hungarian autonomy

[edit]Some view Teleki as a moral hero who tried to avoid Hungary's involvement in World War II. He sent Tibor Eckhardt, a high ranking Smallholders Party politician, to the United States with $5 million for the Hungarian Minister in the United States, János Pelényi, to prepare the Hungarian government in exile, for when he and Regent Horthy would have to leave the country. According to supporters of this view, his object was to save what could be saved, under political and military pressure from Nazi Germany, and like the Polish government in exile, to try to survive in some fashion during the war years to come.

Teleki holds Hungary to "Non-belligerent" status

[edit]

Rejoining the government in 1938 as Minister of Education, Teleki supported Germany's take over of Czechoslovakia with the hopes that the dismemberment of Hungary completed in the 1920 Treaty of Trianon would be undone. On 16 February 1939, Hungarian Prime Minister Béla Imrédy, who had been known as a pro-fascist, anti-Semitic leader, was forced from office after it was revealed that he was of Jewish descent. Teleki became Prime minister for the second time on 15 February 1939. While he strove to close down several fascist political parties, he did nothing to end the existing anti-Semitic laws.[10]

On 24 August 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, which stipulated the Soviet Union's long-standing "interest" in Bessarabia, Romania. One week later, on 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland and demanded the use of the Hungarian railway system through Kassa (then in Hungary) so that German troops could attack Poland from the south. Hungary traditionally had strong ties with Poland, and Teleki refused Germany's demand. Horthy told the German ambassador that "he would sooner blow up the rail lines than to participate in an attack on Poland" (which would completely paralyse the only railway connection from Hungary to Poland, if the Germans decided to march through Hungary without permission).[14][15] Hungary declared that it was a "non-belligerent" nation and refused to allow German forces to travel through or over Hungary to attack Poland. As a result of Teleki's refusal to co-operate with Germany, during the autumn of 1939 and the summer of 1940 more than 100,000 Polish soldiers, and hundreds of thousands of civilians, many of them Jewish, escaped from Poland and crossed the border into Hungary. The Hungarian government then permitted the Polish Red Cross and the Polish Catholic Church to operate in the open.[16] The Polish soldiers were formally interned, but most of them managed to flee to France by spring of 1940, thanks to the indulgent or friendly attitude of officials.

However, with Germany's seizure of Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland, the buffer nations between Hungary and the belligerent nations of Germany and Soviet Union had evaporated. Germany made economic demands on Hungary to support the war, and offered to repay with arms deliveries, but because of developments in the Balkans, they were routed to the Romanian Army instead.[17]

In his diaries, Italian Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini's son-in-law, wrote that during a visit to Rome by Teleki in March 1940, Teleki "has avoided taking any open position one way or the other but has not hidden his sympathy for the Western Powers and fears an integral German victory like the plague".[18] Ciano reported that Teleki later said that he hoped "for the defeat of Germany, not a complete defeat—that might provoke violent shocks—but a kind of defeat that would blunt her teeth and claws for a long time".[18]

Germany demands Hungary's assistance

[edit]

In 1940, Germany used the Soviet Union's imminent movement to take over Bessarabia as an excuse to prepare to occupy the vital Romanian oil fields. Germany's General Staff approached Hungary's General Staff and sought passage of its troops through Hungary and for Hungary's participation in the takeover. Germany held out Transylvania as Hungary's reward. The Hungarian government resisted, desired to remain neutral and held out some hope for assistance from the Italians. Hungary sent a special envoy to Rome: "For the Hungarians there arises the problem either of letting the Germans pass, or opposing them with force. In either case the Hungarian liberty would come to an end". Mussolini replied, "How could this ever be since I am Hitler's ally and intend to remain so?"[18] However, Teleki allowed German troops to cross Hungarian territory into southern Romania, with the reward in August 1940 of the return to Hungary of a large part of Teleki's ancestral Transylvanian homeland in the Second Vienna Award. In November, Teleki's government signed the Tripartite Pact, a move that would come back to haunt him only a few months later.

In March 1941, Teleki strongly objected to Hungarian participation in the invasion of Yugoslavia.[19] Hungary's resistance to aiding Germany caused German mistrust. Hungary was not informed of Hitler's top-secret preparations for invading the Soviet Union and was not initially part of the invasion. "Hungary, in the period of preparation for Barbarossa, is not to be counted as an ally beyond the present status...."

Furthermore, German troops were not to cross Hungarian territories, and Hungarian airfields were not to be used by the Luftwaffe, according to the new directives of the High Command on 22 March 1941.[20] Teleki believed that only a Danubian Federation could help the Central and Eastern European states (Austria, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Romania and Bulgaria) escape Germany's domination.

In the book, Transylvania The Land Beyond the Forest Louis C. Cornish[21][22] described how Teleki, under constant surveillance by the German Gestapo during 1941, sent a secret communication to contacts in America.[23]

He foresaw clearly the complete defeat of Nazi Germany, and the European chaos that would result from the war. He believed that no future was conceivable for any of the minor nations in Eastern and Central Europe if they tried to continue to live their isolated national lives. He asked his friends in America to help them establish a federal system, to federate. This alone could secure for them the two major assets of national life: first, political and military security, and, second, economic prosperity. Hungary, he emphasized, stood ready to join in such collaboration, provided it was firmly based on the complete equality of all the members states.[23]

In 1941, the American journalist Dorothy Thompson supported the statement of others: "I took from Count Teleki's office a monograph which he had written upon the structure of European nations. A distinguished geographer, he was developing a plan for regional federation, based upon geographical and economic realities".[23] Teleki received no response to his ideas and was left to resolve the situation on his own.

Teleki must choose between Axis and Allies

[edit]The event that eventually led to Teleki's suicide began on 25 March 1941 when Yugoslav Prime Minister Dragisa Cvetkovic and Yugoslav Minister for Foreign Affairs Aleksandar Cincar Marković travelled to Vienna and signed the Tripartite Pact. In the late evening on 26/27 March 1941, Air Force Generals Dušan Simović and Borivoje Mirković had executed a bloodless coup d'état, refuted signatures on the alliance and accepted a British guarantee of security instead. Germany saw its southern flank potentially exposed just as it was preparing Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. Germany planned the invasion of Yugoslavia (Directive No. 25) to compel it to remain part of the Axis. Hitler used Hungary's membership in the Tripartite Pact to demand that Hungary join in. Döme Sztójay, the Hungarian ambassador to Germany, was sent home by air with a message for Horthy:

Yugoslavia will be annihilated, for she has just renounced publicly the policy of understanding with the Axis. The greater part of the German armed forces must pass through Hungary but the principal attack will not be made on the Hungarian sector. Here the Hungarian Army should intervene, and, in return for its co-operation, Hungary will be able to reoccupy all those former territories which she had been forced at one time to cede to Yugoslavia. The matter is urgent. An immediate and affirmative reply is requested.[24]

Teleki had signed a non-aggression pact, the Treaty of Eternal Friendship, with Yugoslavia on 12 December 1940, only five months earlier, and would not assent to assisting with the invasion.[25] Teleki's government chose a middle ground, opting to remain out of the German-Yugoslav conflict unless either Hungarian minorities were in danger or Yugoslavia collapsed. Teleki relayed his government's position to London and sought allowance for Hungary's difficult position.[26]

On 3 April 1941, Teleki received a telegram from the Hungarian minister in London that British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden had threatened to break diplomatic relations with Hungary if it did not actively resist the passage of German troops across its territory and to declare war if it attacked Yugoslavia.

Teleki's enduring desire was to keep Hungary non-aligned but he could not ignore Nazi Germany's dominant influence. Teleki was now faced with two bad choices. He could continue to resist Germany's demands for its help in the invasion of Yugoslavia although he knew that would likely mean that after Germany conquered Yugoslavia, it would next turn its attention to Hungary, as had happened to Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland. He could allow German troops to cross Hungarian territory even though it would betray Yugoslavia and lead the Allies to declare war on Hungary.[24]

Horthy, who had resisted Germany's pressure, agreed to Germany's demands. Teleki met with the cabinet council that evening. He complained that Horthy had "told me thirty-four times that he would never make war for foreign interests, and now he has changed his mind".[27]

Before Teleki could chart a course through the political thicket, the decision was torn from him by General Henrik Werth, the chief of the Hungarian General Staff. Without the sanction of the Hungarian government, Werth, of German origin, made private arrangements with the German High Command for the transport of the German troops across Hungary. Teleki denounced Werth's action as treason.[24]

Germany enters Hungary, Teleki commits suicide

[edit]

Shortly after 9:00 p.m., he left the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for his apartment in the Sándor Palace. At around midnight, he received a call that is thought to have informed him that the German army had just started its march into Hungary.[24][25] Teleki committed suicide with a pistol during the night of 3 April 1941 and was found the next morning. His suicide note said in part:

"We broke our word, – out of cowardice [...] The nation feels it, and we have thrown away its honor. We have allied ourselves to scoundrels [...] We will become body-snatchers! A nation of trash. I did not hold you back. I am guilty."[28]

Winston Churchill later wrote, "His suicide was a sacrifice to absolve himself and his people from guilt in the German attack on Yugoslavia."[29] On 6 April 1941, Germany launched Operation Punishment (Unternehmen Strafgericht), the bombing of Belgrade, Yugoslavia. Some historians consider Teleki's suicide an act of patriotism.[30] Britain shortly afterward broke diplomatic relations but did not declare war until December.

Befitting his commitment to Scouting and to Hungary, Teleki was buried at Gödöllő, the location of the Royal Palace.

Legacy

[edit]From Philo-Semitism to anti-Semitism

[edit]Teleki is considered "one of the most consistently unaccommodating anti-Semitic politicians of the post-Trianon period".[31] His attitude towards Jews parallels the changing demographic and social situation in Hungary before and after World War I. In the Austro-Hungarian empire the generally fiercely patriotic Hungarian Jews were securing the tenuous Hungarian majority in the Hungarian kingdom.[32] Consequently, Teleki stated at the peace conference of 1919 that "the majority of the Hungarian Jews have completely assimilated to the Hungarians [...] from a social point of view, the Hungarian Jews are not Jews any more but Hungarians."[33] After 1920, with a greatly reduced Hungarian territory, Teleki changed his mind about the Hungarian Jews: he regarded the Jews as a "problem of life and death for the Hungarian people".[33] After Regent Horthy appointed Teleki Prime Minister on 19 July 1920 he introduced the first anti-Semitic laws introduced in Europe after the First World War, the so-called "Numerus clausus Act" of 22 September 1920[34] which allowed Jews to attend universities only in a direct relation to their proportion of the Hungarian population.[35] He and his government resigned less than a year later on 14 April 1921 when the former king, Karl IV, attempted to retake Hungary's throne.

From 1921 until 1938, Teleki was a professor at Budapest University. While there, journalists asked him what he thought about the anti-Jewish violence that had occurred on the university campus. He replied: "This din does not bother me. In any case, the students take examinations that test their knowledge of the sea and this din is aptly suited to that of the sea."[36]

Due to the feudal nature of pre-War Hungarian society, where both rich and impoverished aristocrats tried to maintain an "aristocratic" life style and a disadvantaged peasant class had no means of learning and social mobility, the Hungarian Jews constituted a disproportionally large part of the Hungarian middle class.[37] In the 1930 census, Jews comprised 5.1% of the population, but among physicians 54.5 percent were Jewish, journalists 31.7%, and lawyers 49.2%. Persons of Jewish faith controlled four of the five major banks, from 19.5 to 33% of the national income, and around 80 percent of the country's industry.[38] Already after the short lived Hungarian Soviet Republic (21 March – 1 August 1919), whose leaders, concomitantly with their middle class origins, were often of Jewish parentage, and even more after the worldwide depression struck in the late 1920s and early 1930s, which conversely was associated with Jewish wealth and financial power, the country's Jews were made scapegoats for all of Hungary's economic, political and social plights.[39]

After a period of considerable economic turbulence and a general political turn to the far right, Teleki became Prime Minister once again on 16 February 1939. Although considered an Anglophile, one of the first things he did in Parliament was to push the Second Anti-Jewish act initiated by his predecessor Béla Imrédy.[40] This was the first law which defined the term "Jew" in explicitly racial terms: "A person belonging to the Jewish denomination is at the same time a member of the Jewish racial community and it is natural that the cessation of membership in the Jewish denomination does not result in any change in that person’s association with the racial community."[41] It forbade Jews to hold any government position, to be editors, publishers, producers or directors. It restated and reinforced the Numerus Clausus act of 1920 and extended its provisions (representation according to proportion of population) to the business world, regulating even the number of Jewish employees (one in five or two in nine maximum, depending on the size).[42] These laws would affect up to 825,000 Jews, who lived in territory reacquired by Hungary in 1941.

Teleki promulgated Law No. II relating to national defense,[43] on 11 March 1939, and signed it into law on 12 May of the same year.[44] The text of the bill stipulated that all young Jewish men of arms-bearing age join forced-labor service. In 1940, this compulsory service was extended to all able-bodied male Jews. As a result of the laws established during Teleki's tenure, 15,000–35,000 Jews in the re-acquired part of Czechoslovakia, who had difficulty in proving their former Hungarian citizenship, were deported.[45]

These Jews, without Hungarian citizenship, were sent to a location near Kamenets-Podolski, where in one of the first acts of mass killing during World War II, all but two thousand of these individuals were executed by the Nazi Einsatzgruppe (mobile killing unit).[46][47]

Teleki wrote the preamble to the Second Anti-Jewish Law (1939)[48] and prepared the Third Anti-Jewish Law in 1940.[48] He also signed 52 anti-Jewish decrees during his rule, and members of his government issued 56 further decrees against Jews.[49]

Teleki devoted a great deal of energy and political savvy to the passage of the second anti-Jewish bill, stating that he pushed it not for tactical reasons but because of his deep personal convictions.[50] During Teleki's second term in 1940, Hungarian Arrow Cross leader Ferenc Szálasi was given amnesty, and the Nazi movement became stronger.[51]

Although the laws of the Labor Service System were put in effect during Teleki's lifetime, they were radically enforced only after Hungary had entered the war.[52] Then the situation of the Jewish forced laborers, which were organized in labor battalions, commanded by Hungarian military officers, became dire. They were engaged in war-related construction, often subject to extreme cold, and given inadequate shelter, food, and medical care. At least 27,000 Jewish forced laborers died before Germany occupied Hungary in March 1944, after which the Hungarian state authorities in close cooperation with the German "Sonderkommando" of Adolf Eichmann[53] rapidly organized and implemented the mass deportation of Jews to the death camps.[47]

While it is true that tens of thousands of young Hungarians were conscripted into military service at the same time and sent to fight on the Eastern Front against the Soviet Union, often ill-equipped and badly trained, and bore the brunt of the miseries of the German defeat, the Hungarian participation in the Eastern campaign was voluntary,[54] and the suffering of its soldiers was war induced and not deliberately inflicted as with the Jewish labor battalions.[55]

Statue controversy

[edit]In 2004, the Teleki Pál Memorial Committee, initially supported by Budapest mayor Gábor Demszky, proposed erecting a statue by Tibor Rieger in his honor on the 63rd anniversary of his death in front of the palace on Castle Hill where he governed and, finally, committed suicide. Because of his close connection with Hungarian anti-Semitism there was a strong opposition both by Hungarian liberals and Hungarian and international Jewish organizations, especially the Simon Wiesenthal Center and its leader Efraim Zuroff.[56][57] Consequently, the mayor withdrew his support and the Minister of Culture István Hiller canceled the plans. On 5 April 2004, the statue was finally placed in the courtyard of the Catholic Church in the town of Balatonboglár on the shore of Lake Balaton.[58] Balatonboglár had during World War II been host to thousands of Polish refugees who opened in that town one of only two secondary schools for Poles in Europe during 1939–1944. They credited Teleki with opening Hungary's borders to them and named a street in Warsaw for him after the war ended.[59] In 2001 he was posthumously awarded Commander's Cross with Star of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland.[60] In 2020 Teleki earned two monuments in Poland, one in Skierniewice and one in Kraków, both related to his pro-Polish stand during the Polish-Soviet war of 1920.[61]

A street in Borča, a suburb of the Serbian capital Belgrade, was named "Ulica Pala Telekija" ("Pal Teleki Street") in 2011.[62]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Laczo, Feren (22 September 2009). Review: Pal Teleki (1874–1941): The Life of a Controversial Hungarian Politician. The Historian.

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, The Holocaust in Hungary, Columbia University Press, New York 1981, ISBN 0-231-04496-8, Chapter 5. The Teleki Era, pp. 140-191.

- ^ "Teleki Pál – egy ellentmondásos életút". National Geographic Hungary (in Hungarian). 18 February 2004. Archived from the original on 27 March 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- ^ "A kartográfia története" (in Hungarian). Babits Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 17 February 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- ^ Spatiul istoric si etnic romanesc, Editura Militara, Bucuresti, 1992

- ^ "Browse Hungary's detailed ethnographic map made for the Treaty of Trianon online". dailynewshungary.com. 9 May 2017.

- ^ Tilkovszky, Loránt (1974). Pal Teleki. Akadémiai Kiadó. p. 360. ISBN 978-963-05-0371-6.

- ^ a b Papakōnstantinou, Michalēs (1992). Mia Voreioellēnikē polē stē Tourkokratia (in Greek) (1st ed.). Athēna: Vivliopoleion tēs "Hestias" I.D. Kollarou. p. 185. ISBN 960-05-0389-3. OCLC 30320605.

- ^ B. Ablonczy, Pál Teleki (1874–1941): The Life of a Controversial Hungarian Politician, Translated by Thomas, J., and DeKornfeld, H. D., (New York, 2006) p. 49.

- ^ a b "The People's Chronology: 1939 – Political Events". Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ^ Grandjean, Martin (2018). Les réseaux de la coopération intellectuelle. La Société des Nations comme actrice des échanges scientifiques et culturels dans l'entre-deux-guerres [The Networks of Intellectual Cooperation. The League of Nations as an Actor of the Scientific and Cultural Exchanges in the Inter-War Period] (phdthesis) (in French). Lausanne: Université de Lausanne. p. 290.

- ^ John Skinner Wilson (1959). Scouting Round the World (Second Ed.) (PDF). Blandford Press. p. 81.

- ^ John Skinner Wilson (1959). Scouting Round the World (Second Ed.). Blandford Press. p. 165.

- ^ "Hungarians towards the German aggression on Poland".

- ^ Gabor Aron Study Group. "Hungary in the Mirror of the Western World 1938–1958". Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ "Poland in Exile – Escape Route". Archived from the original on 16 October 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- ^ Ranki, Gyorgy (1968). Pamlenyi, Ervin; Tilkovszky, Lorant; Juhasz, Gyula (eds.). A Wilhelmstrasse es Magyarorszdg, "The Wilhelm Street and Hungary". Budapest: Kossuth Konyvkiado. p. 471.Carl von Clodius, Leader of the Economic-Political Department of the German Foreign Ministry to the German Foreign Ministry, 13 January 1940, Doc. No. 299

- ^ a b c Cadzow, John F.; Ludanyi, Andrew; Elteto, Louis J. (1983). Transylvania: the Roots of Ethnic Conflict. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-283-8. quoting The Ciano Diaries, 25 March 1940.

- ^ Szinai, Miklos and Laszlo Szucs, Horthy Miklos, Titkos Iratai (1965). Secret Documents of Nicholas Horthy. Budapest: Kossuth Konyvkiado. pp. 291–292.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) His letter addressed to Horthy gave his reasons in the following words: "We sided with the villains... we shall be bodysnatchers, the most worthless nation". - ^ Documents on German Foreign Policy 1918–1945, Series D, Vol. XlI Directives of the High Command, Fuhrer's Headquarters. Washington: United States Government Printing Office. 22 March 1941. pp. 338–343.

- ^ Cornish, Louis (1947). Transylvania The Land Beyond the Forest. Dorrance & Company.

- ^ Pal Teleki (1923). The Evolution of Hungary and its place in European history (Central and East European series).

- ^ a b c Francis S. Wagner, ed. (1970). Toward a New Central Europe: A Symposium on the Problems of the Danubian Nations. Astor Park, Florida: Danubian Press, Inc.

- ^ a b c d Churchill, Winston (1985). The Grand Alliance. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-41057-8. quoting Ullein-Revicry, Guerre Allemande: Paix Russe, p. 89

- ^ a b Montgomery, John F. (1947). Hungary, the Unwilling Satellite. Simon Publications. ISBN 1-931313-57-1.

- ^ Zoltán Bodolai (1978). The Timeless Nation: the History, Literature, Music, Art and Folklore of the Hungarian Nation. Hungaria Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-9596873-3-0. Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2008.

- ^ Sakmyster, Thomas L. (1994). Hungary's admiral on horseback: Miklós Horthy, 1918–1944. Boulder: East European Monographs. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-88033-293-4.

- ^ Horthy, Miklós; Andrew L. Simon (1957). "The Annotated Memoirs of Admiral Milklós Horthy, Regent of Hungary". Ilona Bowden. Archived from the original on 4 January 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ Churchill, Winston; Keegan, John (1948). The Second World War (Six Volume Boxed Set). Mariner Books. pp. 148. ISBN 978-0-395-41685-3.

- ^ Sonya Yee (27 March 2004). "In Hungary, a Belated Holocaust Memorial". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ "In his quiet, ascetic, professorial manner, Teleki was one of the most consistently unaccommodating anti-Semitic politicians of the post-Trianon period." Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 141

- ^ From 45,5% to 50,4%. Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 5

- ^ a b Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 142

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 143

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 30

- ^ Balint Magyar (4 May 2004). "A Hungarian Tragedy (Ha'aretz)". Archived from the original on 22 July 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 4

- ^ The Library of Congress, Researchers, Country Studies, Hungary: The Radical Right in Power

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, pp. 16–23

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 144

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 154 (Quoted from Péter Sipos, Imrédy Béla és a Magyar Megújalas Pártja, Budapest, 1970, p. 85)

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 154-155

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 156

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 292

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 199-207

- ^ The Holocaust in Hungary Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Holocaust Memorial Centre.

- ^ a b "Hungary Before the German Occupation". Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ a b Kádár, Gábor (2001). Self-financing Genocide: the Gold Train, the Becher Case and the Wealth of Hungarian Jews. Zoltán Vági; Translated by Enikó Koncz. Central European University Press. ISBN 9789639241534. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014.

- ^ Karsai, László: Még egy szobrot Teleki Pálnak? Archived 25 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Magyar Narancs, 19 February 2004.

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 153. Quoted from Miklós Lackó, Nyilasok, nemzetiszocialisták 1935–44, Budapest, 1966, p.162-163

- ^ Blamires, Cyprian P. (2006). World Fascism: A Historical Encyclopedia Volume 1. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 1-57607-940-6. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015.

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 295

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 534-535

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 196-197

- ^ Randolph L. Braham: The Politics of Genocide, p. 319, 335–336, 342–343

- ^ Bringing the Dark Past to Light: The Reception of the Holocaust in Postcommunist Europe. Edited and with an introduction by John-Paul-Himka and Joanna Beata Michlic. Nebraska 2013. Chapter 9. Paul Hanebrink: The Memory of the Holocaust in Postcommunist Hungary, p. 261-263

- ^ German webpage with Zuroff-letter: "Protest gegen Entscheidung in Ungarn: Statue für Pál Teleki". Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Department of State: Report on Global Anti-Semitism". 5 January 2005. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- ^ Gyorgyi Jakobi (4 September 2004). "Hero or traitor? – statue of a controversial Hungarian Prime Minister unveiled, but not in Budapest". Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- ^ "Decree of the President of Polish Republic of 23 March 2001" (in Polish).

- ^ "Nowe pomniki: "Przed Bitwą Warszawską" w Skierniewicach oraz Pála Telekiego w Krakowie" (in Polish).

- ^ "REŠENJE O PROMENI NAZIVA ULICA NA TERITORIJI GRADSKIH OPŠTINA: VOŽDOVAC, PALILULA, SAVSKI VENAC". Sl. List Grada Beograda (10). 2011.

External links

[edit]- Works by Paul Teleki at Faded Page (Canada)

- Karsai László: Érvek a Teleki-szobor mellett or here (in Hungarian) (source: Élet és Irodalom, 48. évfolyam, 11. szám)

- About him in Magyar Életrajzi lexikon (in Hungarian)

- Time Magazine, 14 April 1941: End of a Tightrope Walk

- Newspaper clippings about Pál Teleki in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1879 births

- 1941 suicides

- Politicians from Budapest

- Nobility from Budapest

- Teleki family

- National Constitution Party politicians

- Christian National Party (Hungary) politicians

- Christian National Union Party politicians

- Unity Party (Hungary) politicians

- Prime ministers of Hungary

- Foreign ministers of Hungary

- Ministers of education of Hungary

- Members of the House of Representatives of Hungary (1905–1906)

- Members of the House of Representatives of Hungary (1906–1910)

- Members of the House of Representatives of Hungary (1920–1922)

- Members of the House of Representatives of Hungary (1922–1926)

- Members of the House of Representatives of Hungary (1935–1939)

- Members of the House of Representatives of Hungary (1939–1944)

- World Scout Committee members

- Scouting and Guiding in Hungary

- Antisemitism in Hungary

- World War II political leaders

- Hungarian people of World War II

- Hungarian collaborators with Nazi Germany

- Commander's Crosses with Star of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Hungary (civil)

- Hungarian politicians who died by suicide

- Suicides by firearm in Hungary