Cotton library

The Cotton or Cottonian library is a collection of manuscripts that came into the hands of the antiquarian and bibliophile Sir Robert Bruce Cotton MP (1571–1631). The collection of books and materials Sir Robert held was one of the three "foundation collections" of the British Museum in 1753. It is now one of the major collections of the Department of Manuscripts of the British Library.[1] Cotton was of a Shropshire family[2] who originated near Wem[3] and were based in Alkington[4] and employed by the Geneva Bible publisher, statesman and polymath Sir Rowland Hill in the mid 16th century.[5]

After the Dissolution of the Monasteries, many priceless and ancient manuscripts that had belonged to the monastic libraries began to be disseminated among various owners, many of whom were unaware of the cultural value of the manuscripts. Cotton's skill lay in finding, purchasing and preserving these ancient documents. The leading scholars of the era, including Francis Bacon, Walter Raleigh, and James Ussher, came to use Sir Robert's library. Richard James acted as his librarian.[6] The library is of special importance for having preserved the only copy of several works, including Beowulf, The Battle of Maldon, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.[1]

In 1731 the collection was badly damaged by a fire in which 13 manuscripts were completely destroyed, and some 200 seriously damaged. The most important Anglo-Saxon manuscripts had already been copied; the original text of The Battle of Maldon was completely burned.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]At the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries, official state records and important papers were poorly kept, and often retained privately, neglected or destroyed by public officers.

The Cotton family were prominent in Shropshire, and their seat at Alkington, and they were connected to the polymath and sixteenth century statesman Sir Rowland Hill who published the Geneva Bible;[7] and by the seventeenth century Sir Robert Cotton came to hold, and subsequently bound, over a hundred volumes of official papers. There is a theory that the curious incident of the 1643 Battle of Wem was the output of concerns of both sides to secure the Library of Old Sir Rowland at Soulton Hall.[8]

By 1622, his house and library stood immediately north of the Houses of Parliament[9] and was a valuable resource and meeting-place not only for antiquarians and scholars but also for politicians and jurists of various persuasions, including Sir Edward Coke, John Pym, John Selden, Sir John Eliot, and Thomas Wentworth.

Such important evidence was highly valuable at a time when the politics of the realm were historically disputed between king and Parliament. Sir Robert knew his library was of vital public interest and, although he made it freely available to consult, it made him an object of hostility on the part of the government. On 3 November 1629 he was arrested for disseminating a pamphlet held to be seditious (it had actually been written fifteen years earlier by Sir Robert Dudley) and the library was closed on this pretext. Cotton was released on 15 November and the prosecution abandoned the following May, but the library remained shut up until after Sir Robert's death; it was restored to his son and heir, Sir Thomas Cotton, in 1633.[10]

Sir Robert's library included his collection of books, manuscripts, coins and medallions. After his death the collection was maintained and added to by his son, Sir Thomas Cotton (d. 1662), and grandson, Sir John Cotton (d. 1702).[1]

Gift to the nation

[edit]| British Museum Act 1700 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for the better Settling and Preserving the Library kept in the House at Westminster, called Cotton-house, in the Name and Family of the Cottons, for the Benefit of the Publick. |

| Citation | 13 & 14 Will. 3. c. 7 |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 12 June 1701 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | Statute Law Revision Act 1948 |

Status: Repealed | |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

| British Museum Act 1706 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act for the better securing her Majesty's Purchase of Cotton House in Westminster. |

| Citation | 6 Ann. c. 30 (Ruffhead: 5 Ann. c. 30) |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 8 April 1707 |

| Commencement | 3 December 1706 |

Status: Repealed | |

Sir Robert's grandson, Sir John Cotton, donated the Cotton library to Great Britain upon his death in 1702. At this time, Great Britain did not have a national library, and the transfer of the Cotton library to the nation became the basis of what is now the British Library.[1] The early history of the collection is laid out in the introductory recitals to the British Museum Act 1700 (13 & 14 Will. 3. c. 7) that established statutory trusts for the Cotton library:

Sir Robert Cotton late of Connington in the County of Huntingdon Baronett did at his own great Charge and Expense and by the Assistance of the most learned Antiquaries of his Time collect and purchase the most useful Manuscripts Written Books Papers Parchments [Records] and other Memorialls in most Languages of great Use and Service for the Knowledge and Preservation of our Constitution both in Church and State which Manuscripts and other Writings were procured as well from Parts beyond the Seas as from severall Private Collectors of such Antiquities within this Realm [and] are generally esteemed the best Collection of its Kind now any where extant And whereas the said Library has been preserved with the utmost Care and Diligence by the late Sir Thomas Cotton Son of the said Sir Robert and by Sir John Cotton of Westminster now living Grandson of the said Sir Robert and has been very much augmented and enlarged by them and lodged in a very proper Place in the said Sir Johns ancient Mansion House at Westminster which is very convenient for that Purpose And whereas the said Sir John Cotton in pursuance of the Desire and Intentions of his said Father and Grandfather is content and willing that the said Mansion House and Library should continue in his Family and Name and not be sold or otherwise disposed or imbezled and that the said Library should be kept and preserved by the Name of the Cottonian Library for Publick Use & Advantage....[11]

The acquisition of the collection was better secured and managed by the British Museum Act 1706 (6 Ann. c. 30),[12] under which the trustees removed the collections from the ruinous Cotton House, whose site is now covered by the Houses of Parliament. It went first to Essex House, The Strand, which, however, was regarded as a fire risk; and then to Ashburnham House, a little west of the Palace of Westminster. From 1707 the library also housed the Old Royal Library (now "Royal" manuscripts at the British Library). Ashburnham House also became the residence of the keeper of the king's libraries, Richard Bentley (1662–1742), a renowned theologian and classical scholar.

Ashburnham House fire

[edit]

On 23 October 1731, fire broke out in Ashburnham House, in which 13 manuscripts were lost, while over 200 others faced severe destruction and water damage.[13] Bentley escaped while clutching the priceless Codex Alexandrinus under one arm, a scene witnessed and later described in a letter to Charlotte, Lady Sundon, by Robert Freind, headmaster of Westminster School. The manuscript of The Battle of Maldon was destroyed, and that of Beowulf was heavily damaged.[14] Also severely damaged was the Byzantine Cotton Genesis,[1] the illustrations of which nevertheless remain an important record of Late Antique iconography. One of the collection's two original exemplifications of the 1215 Magna Carta, Cotton Charter XIII.31A, was shrivelled in the fire, and its seal badly melted.[15]

Arthur Onslow, Speaker of the House of Commons, as one of the statutory trustees of the library, directed and personally supervised a remarkable programme of restoration within the resources of his time. The published report of this work is of major importance in bibliography.[16] Copies of some of the lost works had been made, and many of those damaged could be restored in the nineteenth century. However, these early conservation efforts were not always successful: bungled attempts to clean the Magna Carta exemplification rendered it largely illegible to the naked eye.[15][17] More recently, advances in multispectral photography have enabled imaging specialists at the British Library led by Christina Duffy to scan and upload images of previously illegible early English manuscripts damaged in the fire.[18] Images will form part of Fragmentarium (Digital Research Laboratory for Medieval Manuscript Fragments),[19] an international collaboration of libraries and research institutions to catalogue and collate vulnerable manuscript fragments, making them available for research under a Creative Commons public domain license.[20]

British Museum and Library

[edit]In 1753 the Cotton library was transferred to the new British Museum, under the Act of Parliament which established it.[1] At the same time the Sloane Collection and Harley Collection were acquired and added, so that these three became the museum's three "foundation collections". The Royal manuscripts were donated by George II in 1757.[21] In 1973 all these collections passed to the newly established British Library. The British Library continues to organise its Cottonian books according to the famous busts.[22]

Classification

[edit]Sir Robert Cotton had organised his library according to the case, shelf and position of a book within a room twenty-six feet long and six feet wide. Each bookcase in his library was surmounted by a bust of a historical personage, including Augustus Caesar, Cleopatra, Julius Caesar, Nero, Otho, and Vespasian. In total, he had fourteen busts, and his scheme involved a designation of bust name/shelf letter/volume number from left end.[1] Thus, the two most famous of the manuscripts from the Cotton library are "Cotton Vitellius A.xv" and "Cotton Nero A.x". In Cotton's own day, that meant "Under the bust of Vitellius, top shelf (A), and count fifteen over" for the volume containing the Nowell Codex (including Beowulf) and "Go to the bust of Nero, top shelf, tenth book" for the manuscript containing all the works of the Pearl Poet. The manuscripts are still catalogued by these call numbers in the British Library.

According to scholar, Colin Tite, the system according to the busts was probably not in full effect until 1638; however there are notes that suggest that Sir Robert planned to arrange the library in this system before his death in 1631, but was probably, as Tite hypothesises, interrupted during the implementation by the closure of the library in 1629.[23]

In 1696, the first printed catalogue of the Cotton library's holdings was published by Thomas Smith, the librarian of Sir John Cotton, Sir Robert Cotton's grandson. The library's official catalogue was published in 1802 by Joseph Planta, which remained the standard guide to the library's contents until modern times.[23]

Selected manuscripts

[edit]- Augustus

- ii.106 Magna Carta: Exemplification of 1215

- Caligula

- A.ii "A Pistil of Susan" (frag.) (probably by Huchoun)

- A.xv Easter Table Chronicle

- Claudius

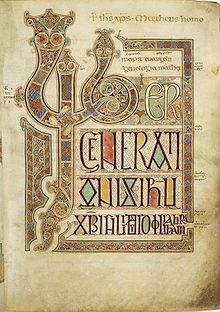

- B.vi Cotton Genesis (fragmentary)

- D.ii Leges Henrici Primi, an illuminated manuscript of a 12th-century legal treatise, copied around 1310[24]

- D.iv fos 48–54 De Iniusta Vexacione Willelmi Episcopi Primi (missing introduction and parts of the conclusion)[25]

- Cleopatra

- A.ii Life of St Modwenna

- Domitian

- A.viii: Bilingual Canterbury Epitome (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle F)

- A.ix fragment of the Bilingual Canterbury Epitome (ASC H), futhorc row

- Faustina

- A.x Additional Glosses to the Glossary in Ælfric's Grammar

- Galba

- A.xviii Athelstan Psalter

- Julius

- A.vi Julius Work Calendar

- A.x Old English Martyrology

- E.vii Ælfric's Lives of Saints

- Nero

- Otho

- A.xii The Battle of Maldon (destroyed in 1731)

- B.x Mary of Egypt (fragmentary)

- B.x.165 Anglo-Saxon rune poem (destroyed in 1731)

- B.xi.2 fragment of a copy of the Parker Chronicle (ASC G or A2, the copy of Winchester Chronicle)

- C.i Ælfric's De creatore et creatura

- C.v Otho-Corpus Gospels (fragmentary)

- Tiberius

- A.vi Abingdon Chronicle I (ASC B)

- A.xiii Hemming's Cartulary

- B.i Abingdon Chronicle II (ASC C)

- B.iv Worcester Chronicle (ASC D)

- B.v Labour of the Months

- C.ii Bede, Ecclesiastical History

- Titus

- D.xxvi Ælfwine's Prayerbook

- Vespasian

- A.i Vespasian Psalter

- D.xiv Ælfric's De duodecim abusivis

- Vitellius

- A.xv Nowell Codex (Beowulf, Judith)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "Cotton Manuscripts". British Library. Archived from the original on 12 September 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ "COTTON, Rowland (1581-1634), of Crooked Lane, London; later of Alkington Hall, Whitchurch and Bellaport Hall, Norton-in-Hales, Salop | History of Parliament Online". www.historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ "The (Almost) Complete Cotton Family Tree". Combermere Abbey. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ "COTTON, Rowland (1581-1634), of Crooked Lane, London; later of Alkington Hall, Whitchurch and Bellaport Hall, Norton-in-Hales, Salop | History of Parliament Online". www.historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ nortoninhales (2 June 2017). "History of Norton Parish". nortoninhales. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ Aikin, John (1812). The Lives of John Selden, Esq., and Archbishop Usher. London: Mathews and Leigh. pp. 375.

- ^ nortoninhales (2 June 2017). "History of Norton Parish". nortoninhales. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "Radio Shropshire - Listen Live - BBC Sounds". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ "LVIII: The Royal Palace of Westminster". Old and New London. Vol. 3. London: Cassel, Petter & Galpin. 1878. pp. 491–502.

Strype thus mentions Cotton House: "In the passage out of Westminster Hall into Old Palace Yard, a little beyond the stairs going up to St. Stephen's Chapel, now the Parliament House" (that is, the present House of Commons), "is the house belonging to the ancient and noble family of the Cottons, wherein is kept a most inestimable library of manuscript volumes found both at home and abroad." Sir Christopher Wren describes the house in his time as in "a very ruinous condition."

- ^ Berkowitz, David Sandler (1988). John Selden's Formative Years. Washington: Folger. pp. 268ff. ISBN 978-0918016911.

- ^ Raithby, John, ed. (1820). "An Act for the better settling and preserving the Library kept in the House at Westminster called Cotton House in the Name and Family of the Cottons for the Benefit of the Publick". Statutes of the Realm (Rot. Parl. 12 § 13 Gul. III. p. 1. n. 7). Vol. 7: 1695–1701. Great Britain Record Commission. pp. 642–643.

- ^ An Act for the better securing Her Majesties Purchase of Cotton House in Westminster.

- ^ "Their Present Miserable State of Cremation".

- ^ Murray, Stuart A. P. (2009). The Library: An Illustrated History. Chicago: Skyhouse. ISBN 978-1616084530.

- ^ a b Breay, Claire; Harrison, Julian, eds. (2015). Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy. London: The British Library. pp. 66, 216–219. ISBN 978-0712357647.

- ^ Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1732). A Report from the Committee Appointed to View the Cottonian Library. House of Commons.

- ^ Duffy, Christina. "Revealing the secrets of the burnt Magna Carta". British Library. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ Duffy, Christina. "Revealing hidden information using multispectral imaging". British Library: Collection Care. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ "Digital Research Laboratory for Medieval Manuscript Fragments". Fragmentarium. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ Dunning, Andrew. "Fragmentarium and the burnt Anglo-Saxon fragments". British Library: Medieval Manuscripts. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ "Manuscripts: Closed Collections". British Library. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ Murray, Stuart. 2009. The library: an illustrated history. Chicago, ALA Editions

- ^ a b Tite, Colin G. C. (1980). "The Early Catalogues of the Cottonian Library". The British Library Journal. 6 (2): 144–157.

- ^ Downer, L. J. (1972). "Introduction". In Downer, L. J. (ed.). Leges Henrici Primi. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780198253013. OCLC 389304.

- ^ Offler, H. S. (1951). "The Tractate De Iniusta Vexacione Willelmi Episcopi Primi". The English Historical Review. 66 (260): 321–341. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXVI.CCLX.321. JSTOR 555778.

Literature

[edit]- Tite, Colin G. C. (1994). The Manuscript Library of Sir Robert Cotton. Panizzi Lectures 1993. London: British Library. ISBN 978-0712303590.

- Wright, Christopher, ed. (1997). Sir Robert Cotton as Collector. London: British Library. ISBN 0712303588.

- A Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Cottonian Library. To Which Are Added Many Emendations and Additions. With an Appendix Containing an Account of the Damage Sustained by the Fire in 1731, and Also a Catalogue of the Charters Preserved in the Same Library. London: Hooper. 1777.

- Planta, Joseph (1802). A Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Cottonian Library Deposited in the British Museum. London: Hansard.

External links

[edit]- "Cotton manuscripts". Collection Guides. British Library. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- British Library Digitized Manuscripts Online Archived 10 October 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- British Library Images Online

- "Cotton Manuscripts Project: This project assisted the British Library in updating the catalogues of the manuscript library of Sir Robert Cotton (1586-1631)". University of Sheffield. 11 July 1997.