Corseae

Corseae or Korsiai (Ancient Greek: Κορσίαι or Κορσιαί[1]) was a port of ancient Boeotia on the Corinthian Gulf.[2] It appears from Pliny the Elder that this town was distinct from Corseia, also in the western part of Boeotia, and that it was distinguished from the other by the name of Thebae Corsicae,[3] that is the Corseae near or belonging to Thebes.

Toponymy

[edit]As to toponymy, it has been suggested that Demosthenes referred to Corseia (Κορσεία) in his speech On the False Embassy, a town located in the northwest of the region, bordering on Ozolian Locris;[4][5] but in spite of the fact that the Athenian orator mentions Orchomenus, Coroneia and Tilphossaeum bordering on Κορσεία, the citations of Harpocration,[6] the Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax,[2] and Stephanus of Byzantium,[1] have led the modern historiographers to seriously consider its location in southern Boeotia, hypothesized further by an inscription of Delphi containing a list of theorodokoi of Corseia from c. 230-210 BCE.[7][8]

Consequently, P. Roesch and other historians argue that the strategy of the Phocians to dominate the Boeotian coast through the fortification or occupation of cities during the Third Sacred War - a campaign reported by Diodorus Siculus[9] and by Demosthenes[4] - would not make sense to involve Corseia, a northern town far from the sea, since it did not meet the geographical and historical conditions referred to in the mentioned texts. In his choice of Corseae instead of Corsiea, P. Roesch considered five points: be in Boeotia, have some importance, be walled, have easy access from Phocis and constitute a penetration in central Boeotia toward Thebes.[10] W. K. Pritchett and John M. Fossey disagree with Étienne and Knoepfler.[11] They argue that the craggy territory of Corseae made access difficult from neighboring towns and from Phocis, and they infer from passages of Xenophon,[12] Pausanias,[13] and Diodorus Siculus,[14] that if in 371 BCE, the Spartan King Cleombrotus I was forced to return to Sparta from Phocis, marching through southern Boeotia, instead of crossing through Coroneia, it was because the Phocians controlled that city that dominated the central Boeotian route;[15] so they did not need to own corsairs, because from Corseia they not only enjoyed an extraordinary place to monitor the Locrian coast, but also because from there they could prevent a joint Locrian-Boeotian expedition against Orchomenus.[16]

The Spanish classical philologists, Juan José Torres Esbarranch and Juan Manuel Guzmán Hermida, place it near Opus and on the sea, in the area of Mount Helicon.[17]

In the year 346 BCE, it was destroyed by the Thebans, its walls demolished and like Orchomenus and Coronea perhaps it was subdued to slavery.[4][18] Subsequently, it was rebuilt.

Archaeology

[edit]The demonym Corsieus (κορσιεύς) is recorded in a treaty signed with its neighbor Thisbae at the beginning of the 2nd century BCE[19] and in an internal decree of proxenia.[20]

Another epigraphic finding shows that at the end of the 4th century BCE, it was not an independent polis (city-state), but belonged to the territory of Thespiae.[21] The text also alludes to a local cult of Hera.[22]

Although the name of its territory is unknown, its size has been estimated at about 40 square kilometres (15 sq mi).[23] It was rebuilt not long after it was devastated in 346 BCE, as evidenced by archeology and the epigraphy of the place.[24]

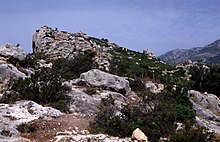

The only written reference to its walls is provided by Diodorus in his description of the Phocian occupation of Corseae, Orchomenus and Coroneia during the Third Sacred War.[25][26] Archaeological excavations have found remains of the walled perimeter: a trapezoidal wall section that protected the acropolis and the lower city, on its east, north and west sides. The south side was naturally defended with precipices. The fortifications are from the years after the Battle of Leuctra (371 BCE), and were surely demolished by the Theban troops in 346 BCE as Demosthenes affirms. Subsequently, before the end of the century, Corseae was fortified with isodomic ashlars. The walls enclosed residential neighborhoods occupying an area of about 1 hectare (2.5 acres).[27]

According to John Bintliff, the inhabited area would range from 1.7 to 4.5 hectares (4.2 to 11.1 acres).[28] The settlement could be traced back to the initial Heladic period. The remains found are from the geometric, archaic and classical periods.[29]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Stephanus of Byzantium. Ethnica. Vol. s.v.

- ^ a b Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax, 38

- ^ "Thebis quae Corsicae cognominatae sunt juxta Heliconem," Pliny. Naturalis Historia. Vol. 4.3.4.

- ^ a b c Demosthenes, On the False Embassy, 141.

- ^ Étienne & Knoepfler 1976, pp. 32–41

- ^ Harpocration, K77

- ^ Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 36,500

- ^ For more details, see Étienne & Knoepfler 1976, p. 38, note 133

- ^ Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca historica (Historical Library). Vol. 16.56-58.

- ^ Étienne & Knoepfler 1976, pp. 38–39; Cf. Roesch, P. (1972). Akten des VI. Intern. Kongresses fur gr. und lat. Epigrafik, Munich, p. 268

- ^ Fossey 1988.

- ^ Xenophon. Hellenica. Vol. 6.4.3.

- ^ Pausanias (1918). "13.3". Description of Greece. Vol. 9. Translated by W. H. S. Jones; H. A. Ormerod. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press; William Heinemann – via Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca historica (Historical Library). Vol. 15.52.1-53.3.

- ^ Pritchett, W K (1991). Studies in Ancient Greek Topography , vol. I, edit. Brill, pp. 52-57.

- ^ Étienne & Knoepfler 1976, pp. 40–41

- ^ Juan José Torres Esbarranch; Juan Manuel Guzmán Hermida (2012). Diodoro Sículo, Biblioteca histórica libros XV-XVIII (in Spanish). Madrid: Gredos. p. 266, n. 201. ISBN 978-84-249-2333-4.

- ^ Hansen, Nielsen & 2004, p. 440

- ^ Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 3.342

- ^ Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 22.410

- ^ Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 24.361 and 30.441

- ^ Schachter, Albert (1981). "Cults of Boiotia". Institute of Classical Studies (BICS). London: University of London: 238.

- ^ Fossey 1988, p. 186

- ^ Hansen & Nielsen 2004, p. 440

- ^ Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca historica (Historical Library). Vol. 16.58.1.

- ^ Hansen & Nielsen 2004, p. 440

- ^ Büssing, Hermann; Büssing-Kolbe, Andrea (1972). Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (Hg.) (ed.). ""Chorsiai": eine Boiotische Festung". Archäologischer Anzeiger, Hg 1 (in German). Berlin: de Gruyter Berlin: 79–87.; Fossey, John M. (1986). "Khósthia I". Amsterdam.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bintliff, John (1997). "Further Considerations on the Population of Ancient Boeotia". Recent Developments in the History and Archaeology of Central Greece: Proceedings of the 6th International Boeotian Conference. Oxford: Archaeopress: 231–252. ISBN 08-6054-858-9.

- ^ Fossey 1988, p. 193

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Corseia". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Corseia". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

Bibliography

[edit]- Étienne, R.; Knoepfler, D. (1976). "Hyettos de Béotie et la chronologie des archontes fédéraux entre 250 et 171 avant J.-C". Bulletin de correspondance hellénique (in French). supl. 3. Paris: De Boccard.

- Hansen, Mogens Herman; Nielsen, Thomas Heine (2004). "Boiotia". An inventory of archaic and classical poleis. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-814099-1.

- Fossey, John M. (1988). Topography and population of ancient Boiotia. Chicago.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)