Connective tissue

| Connective tissue | |

|---|---|

Section of epididymis. Connective tissue (blue) is seen supporting the epithelium (purple). | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D003238 |

| FMA | 96404 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Connective tissue is one of the four primary types of animal tissue, along with epithelial tissue, muscle tissue, and nervous tissue.[1] It develops mostly from the mesenchyme, derived from the mesoderm, the middle embryonic germ layer.[2] Connective tissue is found in between other tissues everywhere in the body, including the nervous system. The three meninges, membranes that envelop the brain and spinal cord, are composed of connective tissue. Most types of connective tissue consists of three main components: elastic and collagen fibers, ground substance, and cells.[2] Blood, and lymph are classed as specialized fluid connective tissues that do not contain fiber.[2][3] All are immersed in the body water. The cells of connective tissue include fibroblasts, adipocytes, macrophages, mast cells and leukocytes.

The term "connective tissue" (in German, Bindegewebe) was introduced in 1830 by Johannes Peter Müller. The tissue was already recognized as a distinct class in the 18th century.[4][5]

Types

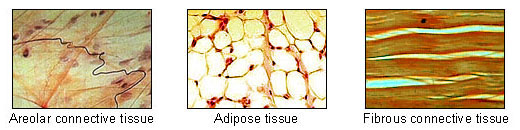

[edit]Connective tissue can be broadly classified into connective tissue proper, and special connective tissue.[6][7] Connective tissue proper includes loose connective tissue, and dense connective tissue. Loose and dense connective tissue are distinguished by the ratio of ground substance to fibrous tissue. Loose connective tissue has much more ground substance and a relative lack of fibrous tissue, while the reverse is true of dense connective tissue.

Loose connective tissue

[edit]Loose connective tissue includes reticular connective tissue, and adipose tissue.

Dense connective tissue

[edit]Dense connective tissue also known as fibrous tissue[8] is subdivided into dense regular and dense irregular connective tissue.[9] Dense regular connective tissue, found in structures such as tendons and ligaments, is characterized by collagen fibers arranged in an orderly parallel fashion, giving it tensile strength in one direction. Dense irregular connective tissue provides strength in multiple directions by its dense bundles of fibers arranged in all directions.[citation needed]

Special connective tissue

[edit]Special connective tissue consists of cartilage, bone, blood and lymph.[10] Other kinds of connective tissues include fibrous, elastic, and lymphoid connective tissues.[11] Fibroareolar tissue is a mix of fibrous and areolar tissue.[12] Fibromuscular tissue is made up of fibrous tissue and muscular tissue. New vascularised connective tissue that forms in the process of wound healing is termed granulation tissue.[13] All of the special connective tissue types have been included as a subset of fascia in the fascial system, with blood and lymph classed as liquid fascia.[14][15]

Bone and cartilage can be further classified as supportive connective tissue. Blood and lymph can also be categorized as fluid connective tissue,[2][16][17] and liquid fascia.[14]

Membranes

[edit]Membranes can be either of connective tissue or epithelial tissue. Connective tissue membranes include the meninges (the three membranes covering the brain and spinal cord) and synovial membranes that line joint cavities.[18] Mucous membranes and serous membranes are epithelial with an underlying layer of loose connective tissue.[18]

Fibrous types

[edit]Fiber types found in the extracellular matrix are collagen fibers, elastic fibers, and reticular fibers.[19] Ground substance is a clear, colorless, and viscous fluid containing glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans allowing fixation of Collagen fibers in intercellular spaces. Examples of non-fibrous connective tissue include adipose tissue (fat) and blood. Adipose tissue gives "mechanical cushioning" to the body, among other functions.[20][21] Although there is no dense collagen network in adipose tissue, groups of adipose cells are kept together by collagen fibers and collagen sheets in order to keep fat tissue under compression in place (for example, the sole of the foot). Both the ground substance and proteins (fibers) create the matrix for connective tissue.

Type I collagen is present in many forms of connective tissue, and makes up about 25% of the total protein content of the mammalian body.[22]

| Tissue | Purpose | Components | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen fibers | Bind bones and other tissues to each other | Alpha polypeptide chains | tendon, ligament, skin, cornea, cartilage, bone, blood vessels, gut, and intervertebral disc. |

| Elastic fibers | Allow organs like arteries and lungs to recoil | Elastic microfibril and elastin | extracellular matrix |

| Reticular fibers | Form a scaffolding for other cells | Type III collagen | liver, bone marrow, and lymphatic organs |

Function

[edit]

Connective tissue has a wide variety of functions that depend on the types of cells and the different classes of fibers involved. Loose and dense irregular connective tissue, formed mainly by fibroblasts and collagen fibers, have an important role in providing a medium for oxygen and nutrients to diffuse from capillaries to cells, and carbon dioxide and waste substances to diffuse from cells back into circulation. They also allow organs to resist stretching and tearing forces. Dense regular connective tissue, which forms organized structures, is a major functional component of tendons, ligaments and aponeuroses, and is also found in highly specialized organs such as the cornea.[23]: 161 Elastic fibers, made from elastin and fibrillin, also provide resistance to stretch forces.[23]: 171 They are found in the walls of large blood vessels and in certain ligaments, particularly in the ligamenta flava.[23]: 173

In hematopoietic and lymphatic tissues, reticular fibers made by reticular cells provide the stroma—or structural support—for the parenchyma (that is, the bulk of functional substance) of the organ.[23]: 171

Mesenchyme is a type of connective tissue found in developing organs of embryos that is capable of differentiation into all types of mature connective tissue.[24] Another type of relatively undifferentiated connective tissue is the mucous connective tissue known as Wharton's jelly, found inside the umbilical cord.[23]: 160 This tissue is no longer present after birth, leaving only scattered mesenchymal cells throughout the body.[25]

Various types of specialized tissues and cells are classified under the spectrum of connective tissue, and are as diverse as brown and white adipose tissue, blood, cartilage and bone.[23]: 158 Cells of the immune system—such as macrophages, mast cells, plasma cells, and eosinophils—are found scattered in loose connective tissue, providing the ground for starting inflammatory and immune responses upon the detection of antigens.[23]: 161

Clinical significance

[edit]There are many types of connective tissue disorders, such as:

- Connective tissue neoplasms including sarcomas such as hemangiopericytoma and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in nervous tissue.

- Congenital diseases include Marfan syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.

- Myxomatous degeneration – a pathological weakening of connective tissue.

- Mixed connective tissue disease – a disease of the autoimmune system, also undifferentiated connective tissue disease.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) – a major autoimmune disease of connective tissue

- Scurvy, caused by a deficiency of vitamin C which is necessary for the synthesis of collagen.

- Fibromuscular dysplasia is a disease of the blood vessels that leads to an abnormal growth in the arterial wall.

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Biga, Lindsay M.; Dawson, Sierra; Harwell, Amy (26 September 2019). "4.1 Types of Tissues". Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d Biga, Lindsay M.; Dawson, Sierra; Harwell, Amy; Hopkins, Robin; Kaufmann, Joel; LeMaster, Mike; Matern, Philip; Morrison-Graham, Katie; Quick, Devon (2019), "4.3 Connective Tissue Supports and Protects", Anatomy & Physiology, OpenStax/Oregon State University, retrieved 16 April 2021

- ^ "5.3.4: Fluid Tissues". Biology LibreTexts. 21 May 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Mathews, M. B. (1975). Connective Tissue, Macromolecular Structure Evolution. Springer-Verlag, Berlin and New York. link.

- ^ Aterman, K. (1981). "Connective tissue: An eclectic historical review with particular reference to the liver". The Histochemical Journal. 13 (3): 341–396. doi:10.1007/BF01005055. PMID 7019165. S2CID 22765625.

- ^ Shostak, Stanley. "Connective Tissues". Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ Carol Mattson Porth; Glenn Matfin (1 October 2010). Essentials of Pathophysiology: Concepts of Altered Health States. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-1582557243. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ "def/fibrous-connective-tissue". www.cancer.gov. 2 February 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- ^ Potter, Hugh. "The Connective Tissues". Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ Caceci, Thomas. "Connective Tisues". Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ King, David. "Histology Intro". Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ "Medical Definition of FIBROAREOLAR". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ "Granulation Tissue Definition". Memidex. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ^ a b Bordoni, Bruno; Mahabadi, Navid; Varacallo, Matthew (2022). "Anatomy, Fascia". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29630284. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ Schleip, R; Hedley, G; Yucesoy, CA (October 2019). "Fascial nomenclature: Update on related consensus process". Clinical Anatomy. 32 (7): 929–933. doi:10.1002/ca.23423. PMC 6852276. PMID 31183880.

- ^ "Supporting Connective Tissue | Human Anatomy and Physiology Lab (BSB 141)". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Karki, Gaurab (23 February 2018). "Fluid or liquid connective tissue: blood and lymph". Online Biology Notes. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Membranes | SEER Training". training.seer.cancer.gov. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ Ushiki, T (June 2002). "Collagen fibers, reticular fibers and elastic fibers. A comprehensive understanding from a morphological viewpoint". Archives of Histology and Cytology. 65 (2): 109–26. doi:10.1679/aohc.65.109. PMID 12164335.

- ^ Xu, H.; et al. (2008). "Monitoring Tissue Engineering Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging". Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering. 106 (6): 515–527. doi:10.1263/jbb.106.515. PMID 19134545. S2CID 3294995.

- ^ Laclaustra, M.; et al. (2007). "Metabolic syndrome pathophysiology: The role of adiposetissue". Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 17 (2): 125–139. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2006.10.005. PMC 4426988. PMID 17270403.

- ^ Di Lullo; G. A. (2002). "Mapping the Ligand-binding Sites and Disease-associated Mutations on the Most Abundant Protein in the Human, Type I Collagen". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (6): 4223–31. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110709200. PMID 11704682.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ross M, Pawlina W (2011). Histology: A Text and Atlas (6th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 158–97. ISBN 978-0781772006.

- ^ Young B, Woodford P, O'Dowd G (2013). Wheater's Functional Histology: A Text and Colour Atlas (6th ed.). Elsevier. p. 65. ISBN 978-0702047473.

- ^

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (26 June 2023). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 4.3 Connective Tissue supports and protects. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (26 June 2023). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 4.3 Connective Tissue supports and protects. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

External links

[edit]- Overview, University of Kansas Archived 26 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Connective tissue atlas, University of Iowa

- Heritable disorders of connective tissue US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

- Connective tissue photomicrographs