Letterpress printing

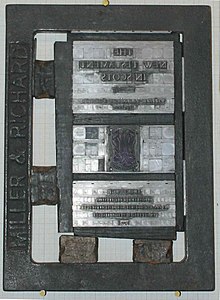

Letterpress printing is a technique of relief printing for producing many copies by repeated direct impression of an inked, raised surface against individual sheets of paper or a continuous roll of paper.[1] A worker composes and locks movable type into the "bed" or "chase" of a press, inks it, and presses paper against it to transfer the ink from the type, which creates an impression on the paper.

In practice, letterpress also includes wood engravings; photo-etched zinc plates ("cuts"); linoleum blocks, which can be used alongside metal type; wood type in a single operation; stereotypes; and electrotypes of type and blocks.[2] With certain letterpress units, it is also possible to join movable type with slugs cast using hot metal typesetting. In theory, anything that is "type high" (i.e. it forms a layer exactly 0.918 inches thick between the bed and the paper) can be printed using letterpress.[3]

Letterpress printing was the normal form of printing text from its invention by Johannes Gutenberg in the mid-15th century through the 19th century, and remained in wide use for books and other uses until the second half of the 20th century. The development of offset printing in the early 20th century gradually supplanted its role in printing books and newspapers. More recently, letterpress printing has seen a revival in an artisanal form.

History

[edit]

Movable type printing was first invented in China using ceramic type in AD 1040 during the Northern Song dynasty by the inventor Bi Sheng (990–1051).[4]

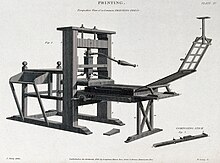

Johannes Gutenberg is credited with the development in the West, in about 1440, of modern movable type printing from individually cast, reusable letters set together in a "forme" (frame or chase). Gutenberg also invented a wooden printing press, based on the extant wine press, where the type surface was inked with leather-covered ink balls and paper laid carefully on top by hand, then slid under a padded surface and pressure applied from above by a large threaded screw. It was Gutenberg's "screw press" or hand press that was used to print 180 copies of the Bible. At 1,282 pages, it took him and his staff of 20 almost 3 years to complete. 48 Gutenberg Bibles remain intact today.[5] This form of presswork gradually replaced the hand-copied manuscripts of scribes and illuminators as the most prevalent form of printing.[6] Printers' workshops, previously unknown in Europe before the mid-15th century, were found in every important metropolis by 1500.[6] Later metal presses used a knuckle and lever arrangement instead of the screw, but the principle was the same. Ink rollers made of composition made inking faster and paved the way for further automation.

Industrialization

[edit]

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution and industrial mechanisation, inking was carried out by rollers that passed over the face of the type, then moved out of the way onto an ink plate to pick up a fresh film of ink for the next sheet. Meanwhile, a sheet of paper slid against a hinged platen (see image), which then rapidly pressed onto the type and swung back again as the sheet was removed and the next sheet inserted. As the fresh sheet of paper replaced the printed paper, the now freshly inked rollers ran over the type again. Fully automated 20th-century presses, such as the Kluge and "Original" Heidelberg Platen (the "Windmill"), incorporated pneumatic sheet feed and delivery.

Rotary presses were used for high-speed work. In the oscillating press, the forme slid under a drum around which each sheet of paper was wrapped for the impression, sliding back under the inking rollers while the paper was removed and a new sheet inserted. In a newspaper press, a papier-mâché mixture called a flong was used to make a mould of the entire form of type, then dried and bent, and a curved metal stereotype plate cast against it. The plates were clipped to a rotating drum and could print against a continuous reel of paper at the enormously high speeds required for overnight newspaper production. This invention helped aid the high demand for knowledge during this time period.

North American history

[edit]Canada

[edit]Letterpress printing was introduced in Canada in 1752 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, by John Bushell in the newspaper format.[7] This paper was named the Halifax Gazette and became Canada's first newspaper. Bushell apprenticed under Bartholomew Green in Boston. Green moved to Halifax in 1751 in hopes of starting a newspaper, as there had never been one in the area. Two weeks and a day after the press he was going to use for this new project arrived in Halifax, Green died. Upon receiving word about what happened, Bushell moved to Halifax and continued what Green had started. The Halifax Gazette was first published on March 23, 1752, making Bushell the first letterpress printer in any of the areas that later became Canada. There is only one known surviving copy of the first number, which was found in the Massachusetts Historical Society.[8]

United States

[edit]One of the first forms of letterpress printing in the United States was Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick started by Benjamin Harris. This was the first form of a newspaper with multiple pages in the Americas. The first publication of Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick was September 25, 1690.[9]

Revival and rise of craft letterpress

[edit]

Letterpress started to become largely out-of-date in the 1970s because of the rise of computers and new self-publishing print and publish methods. Many printing establishments went out of business from the 1980s to 1990s and sold their equipment after computers replaced letterpress's abilities more efficiently. These commercial print shops discarded presses, making them affordable and available to artisans throughout the country. Popular presses include, in particular, Vandercook cylinder proof presses and Chandler & Price platen presses. In the UK there is particular affection for the Arab press, built by Josiah Wade in Halifax. Letterpress recently has had a rebirth in popularity because of the "allure of hand-set type"[10] and the differences today between traditional letterpress and computerized printed text. Letterpress is unique and different from standard printing formats that we are currently used to. Letterpress commonly features a relief impression of the type, although this was considered bad printing in traditional letterpress.[11] Letterpress's goal before the recent revival of letterpress was to not show any impression. The type touched the paper slightly to leave a transfer of ink, but did not leave an impression. This is often referred to as "the kiss".[12] An example of this former technique would be newspapers. Some letterpress practitioners today have the distinct goal of showing the impression of type, to distinctly note that it is letterpress, but many printers choose to maintain the integrity of the traditional methods. Printing with too much impression is destructive to both the machines and to the type. Since its revival letterpress has largely been used for fine art and stationery as its traditional use for newspaper printing is no longer relevant for use.

Letterpress is considered a craft as it involves using a skill and is done by hand. Fine letterpress work is crisper than offset litho because of its impression into the paper, giving greater visual definition to the type and artwork,[citation needed] although it is not what letterpress traditionally was meant for. Today, many of these small letterpress shops survive by printing fine editions of books or by printing upscale invitations, stationery, and greeting cards. These methods often use presses that require the press operator to feed paper one sheet at a time by hand. Today, the juxtaposition of this technique and offbeat humor for greeting cards has been proven by letterpress shops to be marketable to independent boutiques and gift shops. Some of these printmakers are just as likely to use new printing methods as old, for instance by printing using photopolymer plates on restored vintage presses.[citation needed]

Evidence of the range and strength of contemporary letterpress printing across North America was documented in The Itinerant Printer, a 320-page book with 1,500 color photos by Christopher Fritton. From 2015–2017 Fritton, a poet, printer, and artist, crisscrossed the United States and Canada traveling 47,000 miles as a "tramp printer" visiting 137 presses, recording his impressions of each studio and documenting the proprietors and their work. A full set of prints and postcards from his travels while researching the book is in the collection of the Library of Congress. Included in many libraries,[13] the book was the subject of Fritton's talks at a Buffalo, New York TED (conference),[14] at the Library of Congress,[15] and at the Los Angeles Printers Fair 2018.[16]

Martha Stewart's influence

[edit]Letterpress publishing has recently undergone a revival in the US, Canada, and the UK, under the general banner of the "Small Press Movement".[17] Renewed interest in letterpress was fueled by Martha Stewart Weddings magazine, which began using pictures of letterpress invitations in the 1990s.[18] In 2004 they state "Great care is taken in choosing the perfect wedding stationery – couples ponder details from the level of formality to the flourishes of the typeface. The method of printing should be no less important, as it can enliven the design exquisitely. That is certainly the case with letterpress."[19] In regards to having printed letterpress invitations, the beauty and texture became appealing to couples who began wanting letterpress invitations instead of engraved, thermographed, or offset-printed invitations.

Education

[edit]The movement has been helped by the emergence of a number of organizations that teach letterpress such as Columbia College Chicago's Center for Book and Paper Arts, Art Center College of Design and Armory Center for the Arts both in Pasadena, Calif., New York's Center for Book Arts, Studio on the Square and The Arm NYC, the Wells College Book Arts Center in Aurora, New York, the San Francisco Center for the Book, Bookworks, Seattle's School of Visual Concepts, Olympia's The Evergreen State College, Black Rock Press, North Carolina State University, Washington, D.C.'s Corcoran College of Art and Design, Penland School of Crafts, the Minnesota Center for Book Arts, the International Printing Museum in Carson, CA, Western Washington University in Bellingham, WA, Old Dominion University in Norfolk, VA, and the Bowehouse Press at VCU in Richmond, VA.

Economical materials

[edit]Affordable copper, magnesium and photopolymer platemakers and milled aluminum bases have allowed letterpress printers to produce type and images derived from digital artwork, fonts and scans. Economical plates have encouraged the rise of "digital letterpress" in the 21st century, allowing a small number of firms to flourish commercially and enabling a larger number of boutique and hobby printers to avoid the limitations and complications of acquiring and composing metal type. At the same time there has been a renaissance in small-scale type foundries to produce new metal type on Monotype equipment, Thompson casters and the original American Type Founders machines.[citation needed]

Process

[edit]The process of letterpress printing consists of several stages: composition, imposition and lock-up, and printing. In a small shop, all would occur in a single room, whereas in larger printing plants, such as with urban newspapers and magazines, each might form a distinct department with its own room, or even floor.

Composition

[edit]

Composition, or typesetting, is the stage where pieces of movable type are assembled to form the desired text. The person charged with composition is called a "compositor" or "typesetter", setting letter by letter and line by line.

Traditionally, as in manual composition, it involves selecting the individual type letters from a type case, placing them in a composing stick, which holds several lines, then transferring those to a larger type galley. By this method the compositor gradually builds out the text of an individual page letter by letter. In mechanical typesetting, it may involve using a keyboard to select the type, or even cast the desired type on the spot, as in hot metal typesetting, which are then added to a galley designed for the product of that process. The first keyboard-actuated typesetting machines to be widely accepted, the Linotype and the Monotype, were introduced in the 1890s.[1]

The Ludlow Typograph Machine, for casting of type-high slugs from hand-gathered brass matrices, was first manufactured in Chicago in 1912 and was widely used until the 1980s. Many are still in use and although no longer manufactured, service and parts are still available for them.

The Elrod machine, invented in 1920, casts strip material from molten metal; leads and slugs that are not type-high (do not print) used for spacing between lines and to fill blank areas of the type page.

After a galley is assembled to fill a page's worth of type, the type is tied together into a single unit so that it may be transported without falling apart. From this bundle a galley proof is made, which is inspected by a proof-reader to make sure that the particular page is accurate.

Imposition

[edit]

Broadly, imposition or imposing is the process by which the tied assemblages of type are converted into a form (or forme) ready to use on the press. A person charged with imposition is a stoneman or stonehand, doing their work on a large, flat imposition stone (though some later ones were instead made of iron).

In the more specific modern sense, imposition is the technique of arranging the various pages of type with respect to one another. Depending on page size and the sheet of paper used, several pages may be printed at once on a single sheet. After printing, these are cut and trimmed before folding or binding. In these steps, the imposition process ensures that the pages face the right direction and in the right order with the correct margins.

Low-height pieces of wood or metal furniture are added to make up the blank areas of a page. The printer uses a mallet to strike a wooden block, which ensures tops (and only the tops) of the raised type blocks are all aligned so they will contact a flat sheet of paper simultaneously.

Lock-up is the final step before printing. The printer removes the cords that hold the type together, and expands the quoins with a key or lever to lock the entire complex of type, blocks, furniture, and chase (frame) into place. This creates the final forme, which the printer takes to the printing press. In a newspaper setting, each page needs a truck to be transported – 2 pages need 2 trucks hence the term double truck. The first copy is proofed again for errors before starting the printing run.

Printing

[edit]

The working of the printing process depends on the type of press used, as well as any of its associated technologies (which varied by time period).

Hand presses generally required two people to operate them: one to ink the type, the other to work the press. Later mechanized jobbing presses require a single operator to feed and remove the paper, as the inking and pressing are done automatically.

The completed sheets are then taken to dry and for finishing, depending on the variety of printed matter being produced. With newspapers, they are taken to a folding machine. Sheets for books are sent for bookbinding.

The output of traditional letterpress printing can be distinguished from that of a digital printer by its debossed lettering or imagery. A traditional letterpress printer made a heavy impression into the stock and producing any indentation at all into the paper would have resulted in the print run being rejected. Part of the skill of operating a traditional letterpress printer was to adjust the machine pressures just right so that the type just kissed the paper, transferring the minimum amount of ink to create the crispest print with no indentation. This was very important as when the print exited the machine and was stacked having too much wet ink and an indentation would have increased the risk of set-off (ink passing from the front of one sheet onto the back of the next sheet on the stack).[20]

Photopolymer plates

[edit]The letterpress printing process remained virtually unchanged until the 1950s when it was replaced with the more efficient and commercially viable offset printing process. The labor-intensive nature of the typesetting and need to store vast amounts of lead or wooden type resulted in the letterpress printing process falling out of favour.

In the 1980s dedicated letterpress practitioners revived the old craft by embracing a new manufacturing method[21] which allowed them to create raised surface printing plates from a negative and a photopolymer plate.[22]

Photopolymer plates are light sensitive. On one side the surface is cured when it is exposed to ultraviolet light and the other side is a metal or plastic backing that can be mounted on a base. The relief printing surface is created by placing a negative of the piece to be printed on the photosensitive side of the plate; the light passing through the clear regions of the negative causes the photopolymer to harden. The unexposed areas remain soft and can be washed away with water.

With these new printing plates, designers were no longer inhibited by the limitations of handset wooden or lead type. New design possibilities emerged and the letterpress printing process experienced a revival. Today it is in high demand for wedding stationery however there are limitations to what can be printed and designers must adhere to some design for letterpress principles.[23]

Variants on the letterpress

[edit]The invention of ultra-violet curing inks has helped keep the rotary letterpress alive in areas like self-adhesive labels. There is also still a large amount of flexographic printing, a similar process, which uses rubber plates to print on curved or awkward surfaces, and a lesser amount of relief printing from huge wooden letters for lower-quality poster work.

Rotary letterpress machines are still used on a wide scale for printing self-adhesive and non-self-adhesive labels, tube laminate, cup stock, etc. The printing quality achieved by a modern letterpress machine with UV curing is on par with flexo presses. It is more convenient and user friendly than a flexo press. It uses water-wash photopolymer plates, which are as good as any solvent-washed flexo plate. Today even CtP (computer-to-plate) plates are available making it a full-fledged, modern printing process. Because there is no anilox roller in the process, the make-ready time also goes down when compared to a flexo press. Inking is controlled by keys very much similar to an offset press. UV inks for letterpress are in paste form, unlike flexo. Various manufacturers produce UV rotary letterpress machines, viz. Dashen, Nickel, Taiyo Kikai, KoPack, Gallus, etc. – and offer hot/cold foil stamping, rotary die cutting, flatbed die cutting, sheeting, rotary screen printing, adhesive side printing, and inkjet numbering. Central impression presses are more popular than inline presses due to their ease of registration and simple design. Printing of up to nine colours plus varnish is possible with various online converting processes. But as the letterpress machines are the same like a decade before, they can furthermore only be used with one colour of choice simultaneously. If there are more colours needed, they have to be exchanged one after the other.[24]

Craftsmanship

[edit]

Letterpress can produce work of high quality at high speed, but it requires much time to adjust the press for varying thicknesses of type, engravings, and plates called makeready.[1] The process requires a high degree of craftsmanship. It is used by many small presses that produce fine, handmade, limited-edition books, artists' books, and high-end ephemera such as greeting cards and broadsides. Because of the time needed to make letterpress plates and to prepare the press, setting type by hand has become less common with the invention of the photopolymer plate, a photosensitive plastic sheet that can be mounted on metal to bring it up to type high.[1]

To bring out the best attributes of letterpress, printers must understand the capabilities and advantages of the medium. For instance, since most letterpress equipment prints only one color at a time, printing multiple colors requires a separate press run in register with the preceding color. When offset printing arrived in the 1950s, it cost less, and made the color process easier.[25] The inking system on letterpress equipment is the same as offset presses, posing problems for some graphics. Detailed, white (or "knocked out") areas, such as small, serif type, or very fine halftone surrounded by fields of color can fill in with ink and lose definition if rollers are not adjusted correctly.

Current initiatives

[edit]The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (April 2023) |

Several dozen colleges and universities around the United States have either begun or re-activated programs teaching letterpress printing in fully equipped facilities. In many cases these letterpress shops are affiliated with the college's library or art department, and in others they are independent, student-run operations or extracurricular activities sponsored by the college. The College & University Letterpress Printers' Association (CULPA) was founded in 2006 by Abigail Uhteg at the Maryland Institute College of Art to help these schools stay connected and share resources. Many universities offer degree programs such as: Oregon College of Art and Craft, Southwest School of Art, Middle Tennessee State University, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Indiana University, Miami University, Corcoran College of Art and Design, and Rochester Institute of Technology.[26]

The current renaissance of letterpress printing has created a crop of hobby press shops that are owner-operated and driven by a love of the craft. Several larger printers have added an environmental component to the venerable art by using only wind-generated electricity to drive their presses and plant equipment. Notably, a few small boutique letterpress shops are using only solar power.

In Berkeley, California, letterpress printer and lithographer David Lance Goines maintains a studio with a variety of platen and cylinder letterpresses as well as lithography presses.[27] He has drawn attention both from commercial printers and fine artists for his wide knowledge and meticulous skill with letterpress printing. He collaborated with restaurateur and free speech activist Alice Waters, the owner of Chez Panisse, on her book 30 Recipes Suitable for Framing.[28] He has created strikingly colorful large posters for such Bay Area businesses and institutions as Acme Bread and UC Berkeley.[27] Another Berkeley letterpress printer is Peter Rutledge Koch, who focuses on artist books and small published books.[29]

In London, St Bride Library houses a large collection of letterpress information in its collection of 50,000 books: all the classic works on printing technique, visual style, typography, graphic design, calligraphy and more. This is one of the world's foremost collections and is located off Fleet Street in the heart of London's old printing and publishing district. In addition, regular talks, conferences, exhibitions and demonstrations take place.

The St Bride Institute, Edinburgh College of Art, Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design, The Arts University Bournemouth, Plymouth University, University for the Creative Arts Farnham, London College of Communication and Camberwell College of the Arts London run short courses in letterpress as well as offering these facilities as part of their Graphic Design Degree Courses.

The Hamilton Wood Type and Printing Museum in Two Rivers, Wisconsin, houses one of the largest collections of wood type and wood cuts in the world inside one of the Hamilton Manufacturing Company's factory buildings. Also included are presses and vintage prints. The museum holds many workshops and conferences throughout the year and regularly welcomes groups of students from universities from across the United States.

In 2015, the New York Times reported a renaissance of letterpress printing as an art form.[30]

See also

[edit]- Amateur press association – Group of people who self-publish material among themselves

- Offset ink – Type of ink used with offset printing presse

- Punchcutting – Craft used in traditional typography

- List of stationery topics

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Letterpress Printing. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2014. Archived from the original on 2022-01-25. Retrieved 2015-04-17.

- ^ Stewart, Alexander A. (1912). The Printer's Dictionary of Technical Terms. Boston, Mass.: North End Union School of Printing. pp. vi–ix.

- ^ Kafka, Francis (1972). Linoleum Block Printing. Courier Corporation. p. 71. ISBN 9780486203089. Archived from the original on 2022-01-05. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1994). The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 14. ISBN 9780521329958.

- ^ "Over 600 Years of Printing History". beautyofletterpress.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ a b Eisenstein, Elizabeth (2012). The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107632752.

- ^ "Printing and typesetting". Canadian Science and Technology Museum. 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-11-01. Retrieved 2014-11-01.

- ^ "Nova Scotia Archives". Halifax Gazette. 2014. Archived from the original on 2018-08-23. Retrieved 2017-09-03.

- ^ Breig, James (2014). "Early American newspapering". Colonial Williamsburg. Archived from the original on 2014-10-24. Retrieved 2014-11-02.

- ^ Holson, Laura (2006). "Retro printers, grounding the laser jet". The New York Times.

- ^ "Letterpress printing". Graphic Design. 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-11-02. Retrieved 2014-11-02.

- ^ Franklin, Allison (2016). "Resurgence of the Letterpress, Actually Thanks to the Internet". INK SOLV 30 blog. Archived from the original on 2016-01-27. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ^ "the itinerant printer fritton - Search Results". search.worldcat.org. Retrieved 2024-11-22.

- ^ TEDx Talks (2018-01-25). The New American Craftsman | Chris Fritton | TEDxBuffalo. Retrieved 2024-11-22 – via YouTube.

- ^ "The Itinerant Printer: A Look at Contemporary Letterpress Printing Across North America". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2024-11-22.

- ^ Featured speaker Los Angeles Printers Fair 2018 https://www.facebook.com/printmuseum/videos/240254356668108//

- ^ "How Letterpress Printing Came Back from the Dead | Backchannel". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on 2022-01-25. Retrieved 2020-11-09.

- ^ "How the world's old printing presses are being brought back to life". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 2020-11-09. Retrieved 2020-11-09.

- ^ "Letterpress". Martha Stewart Weddings. 2004. Archived from the original on 2014-11-04. Retrieved 2014-11-02.

- ^ "Thoughts on traditional letterpress printing". Meridian Press. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014.

- ^ US patent 4427759, Gruetzmacher, Robert R. & Munger, Stanley H., "Process for preparing an overcoated photopolymer printing plate", issued 1984-January-24, assigned to E. I. Du Pont De Nemours And Company

- ^ US patent 4320188, Heinz, Gerhard; Richter, Peter & Jun, Mong-Jon, "Photopolymerizable compositions containing elastomers and photo-curable elements made therefrom", issued 1982-March-16, assigned to Basf Aktiengesellschaft

- ^ "Designing for Letterpress". MAGVA Design + Letterpress. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ "characteristics of letterpress". Archived from the original on 2018-08-29. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- ^ Bednar, Joseph (November 23, 2010). "Making an Impression". BusinessWest. Archived from the original on May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- ^ "Matriculated Programs". Letterpress Commons. Archived from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ a b Citrawireja, Melati (July 22, 2015). "A visit with David Goines: Berkeley's legendary letterpress printer and lithographer". Berkleyside. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ Waters, Alice. 30 Recipes Suitable for Framing.

- ^ "The Grolier Club Presents a Peter Koch Printer Retrospective". Fine Books & Collections. September 4, 2019. Archived from the original on 2021-07-30. Retrieved 2021-07-31.

- ^ Hoinski, Michael (February 4, 2015). "Artists Find an Audience for Painstaking Letterpress Printing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 3, 2016. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Blumenthal, Joseph. (1973) Art of the printed book, 1455–1955.

- Blumenthal, Joseph. (1977) The Printed Book in America.

- Jury, David (2004). Letterpress: The Allure of the Handmade.

- Lange, Gerald. (1998) Printing digital type on the hand-operated flatbed cylinder press.

- Ryder, John (1977), "Printing for Pleasure, A Practical Guide for Amateurs"

- Stevens, Jen. (2001). Making Books: Design in British Publishing since 1940.

- Ryan, David. (2001). Letter Perfect: The Art of Modernist Typography, 1896–1953.

- Drucker, Johanna. (1997). The Visible Word : Experimental Typography and Modern Art, 1909–1923.

- Auchincloss, Kenneth. "The Second Revival: Fine Printing since World War II". In Printing History No. 41: pp. 3–11.

- Cleeton, Glen U. & Pitkin, Charles W. with revisions by Cornwell, Raymond L. (1963) "General Printing – An illustrated guide to letterpress printing, with hundreds of step-by-step photos".

External links

[edit]- Introduction to Letterpress Printing

- Bibliography of Letterpress Printing

- British Letterpress: information for hobby printers, and specific UK letterpress machines

- The Fine Press Book Association

- Early Rollers and Composition Rollers

- Letterpress Studio Directory

- Letterpress Printing Nostalgia

- Letterpress in Russia

- Amberley Museum Working Letterpress Workshop