Colonisation of Africa

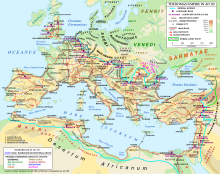

External colonies were first founded in Africa during antiquity. Ancient Greeks and Romans established colonies on the African continent in North Africa, similar to how they established settler-colonies in parts of Eurasia. Some of these endured for centuries; however, popular parlance of colonialism in Africa usually focuses on the European conquests of African states and societies in the Scramble for Africa (1884–1914) during the age of New Imperialism, followed by gradual decolonisation after World War II.

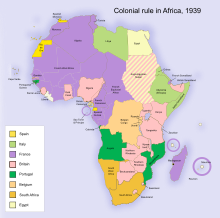

The principal powers involved in the modern colonisation of Africa were Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, Spain, Belgium and Italy. European rule had significant impacts on Africa's societies and the suppression of communal autonomy disrupted local customary practices and caused the irreversible transformation of Africa's socioeconomic systems.[1] Colonies were maintained for the purpose of economic exploitation and extraction of natural resources. In nearly all African countries today, the language used in government and media is the one used by a recent colonial power, though most people speak their native African languages.

Ancient and medieval colonies

[edit]

In the early historical period, colonies were founded in North Africa by migrants from Europe and Western Asia, particularly Greeks and Phoenecians.

Under Egypt's Pharaoh Amasis (570–526 BC) a Greek mercantile colony was established at Naucratis, some 50 miles from the later Alexandria.[2] Greeks colonised Cyrenaica around the same time.[3] There was an attempt in 513 BC to establish a Greek colony between Cyrene and Carthage, which resulted in the combined local and Carthaginian expulsion two years later of the Greek colonists.[4] Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) founded Alexandria during his conquest of Egypt. This became one of the major cities of Hellenistic and Roman times, a trading and cultural centre as well as a military headquarters and communications hub.

Phoenicians established several colonies along the coast of North Africa. Some of these were founded relatively early. For example, Utica was founded c. 1100 BC. Carthage, which means New City, has a traditional foundation date of 814 BC. It was established in what is now Tunisia and became a major power in the Mediterranean by the 4th century BC. The Carthaginians sent out expeditions to explore and establish colonies along Africa's Atlantic coast. A surviving account of such is that of Hanno c. 425 BC.[5]

Carthage encountered and struggled with the Romans. After the third and final war between them, the Third Punic War (150–146 BC), Rome completely destroyed Carthage. Scullard mentions plans by such as Gaius Gracchus in the late 2nd century BC, Julius Caesar and Augustus in the 1st century BC to establish a new Roman colony near the same site. This was established and under Augustus served as the capital city of African continent Roman province of Africa.[6] Gothic Vandals briefly established a kingdom there in the 5th century, which shortly thereafter fell to the Romans again, this time the Byzantines. The whole of Roman/Byzantine North Africa eventually fell to the Arabs in the 7th century. Arabs introduced the Arabic language and Islam in the early medieval period, while a Malayo-Polynesian-speaking group introduced Malagasy to Madagascar even earlier.

Early modern period

[edit]Early European expeditions concentrated on establishing coastal trading posts as a base for trade, while also colonising previously uninhabited islands such as the Cape Verde Islands and São Tomé Island. The Spanish colonised the Canary Islands off the north African coast in the 15th century, causing the genocide of the native Berber population.[7]

The oldest modern city founded by Europeans on the African continent is Cape Town, which was founded by the Dutch East India Company in 1652, as a halfway stop for passing European ships sailing to the east.

Scramble for Africa

[edit]

Established empires—notably Britain, France, Spain and Portugal—had already claimed coastal areas but had not penetrated deeply inland. By 1870, Europeans controlled one tenth of Africa, primarily along the Mediterranean and in the far south. A significant early proponent of colonising inland was King Leopold of Belgium, who oppressed the Congo Basin as his own private domain until 1908. The 1885 Berlin Conference, initiated by Otto von Bismarck to establish international guidelines and avoiding violent disputes among European Powers, formalized the "New Imperialism", driven by the Second Industrial Revolution.[8] This allowed the imperialists to move inland, with relatively few disputes among themselves. The only serious threat of inter-Imperial violence came in the Fashoda Incident of 1898 between Britain and France; It was settled without significant military violence between the colonising countries. Between 1870 and 1914 Europe acquired almost 23,000,000 sq. km —one-fifth of the land area of the globe—to its overseas colonial possessions.

Imperialism generated self-esteem across Europe. The Allies of World War I and World War II made extensive use of African labour and soldiers during the wars.[9][10] In terms of administrative styles, "[t]he French, the Portuguese, the Germans and the Belgians exercised a highly centralised type of administration called 'direct rule.'"[11] The British by contrast sought to rule by identifying local power holders and encouraging or forcing them to administer for the British Empire. This was indirect rule.[12] France ruled from Paris, appointing chiefs individually without considering traditional criteria, but rather loyalty to France. France established two large colonial federations in Africa, French West Africa and French Equatorial Africa. France appointed the state officials, passed laws and had to approve any measures passed by colonial assemblies.

Local groups in German East Africa resisted German enforced labour and taxation. In the Abushiri revolt, the Germans were almost driven out of the area in 1888.[13] A decade later the colony seemed conquered, though, "It had been a long-drawn-out struggle and inland administration centres were in reality little more than a series of small military fortresses." In 1905, the Germans were astonished by the widely supported Maji Maji Rebellion. This resistance was at first successful. However, within a year, the insurrection was suppressed by reinforcing troops armed with machine guns. German attempts to seize control in Southwest Africa also produced ardent resistance, which was very forcefully repressed leading to the Herero and Namaqua Genocide.[14]

King Leopold II of Belgium called his vast private colony the Congo Free State. His barbaric treatment of the Africans sparked a strong international protest and the European powers forced him to relinquish control of the colony to the Belgian Parliament.[15]

Vincent Khapoya notes the significant attention colonial powers paid to the economics of colonisation. This included: acquisition of land, often enforced labour, the introduction of cash crops, sometimes even to the neglect of food crops, changing inter-African trading patterns of pre-colonial times, the introduction of labourers from India, etc. and the continuation of Africa as a source of raw materials for European industry.[16] Colonial powers later focused on abolishing slavery, developing infrastructure, and improving health and education.[17][18][19]

Decolonization

[edit]

Khapoya notes the significant resistance of powers faced to their domination in Africa. Technical superiority enabled conquest and control. Pro-independence Africans recognised the value of European education in dealing with Europeans in Africa. Some Africans established their own churches. Africans also noticed the unequal evidence of gratitude they received for their efforts to support Imperialist countries during the world wars.[20] While European-imposed borders did not correspond to traditional territories, such new territories provided entities to focus efforts by movements for increased political voice up to independence.[21] Among local groups so concerned were professionals such as lawyers and doctors, the petite bourgeoisie (clerks, teachers, small merchants), urban workers, cash crop farmers, peasant farmers, etc. Trade unions and other initially non-political associations evolved into political movements.

While the British sought to follow a process of gradual transfer of power and thus independence, the French policy of assimilation faced some resentment, especially in North Africa.[22] The granting of independence in March 1956 to Morocco and Tunisia allowed a concentration on Algeria where there was a long (1954–62) and bloody armed struggle to achieve independence.[23] When President Charles de Gaulle held a referendum in 1958 on the issue, only Guinea voted for outright independence. Nevertheless, in 1959 France amended the constitution to allow other colonies this option.[24]

Farmers in British East Africa were upset by attempts to take their land and to impose agricultural methods against their wishes and experience. In Tanganyika, Julius Nyerere exerted influence not only among Africans, united by the common Swahili language, but also on some white leaders whose disproportionate voice under a racially weighted constitution was significant. He became the leader of an independent Tanganyika in 1961. In Kenya, whites had evicted African tenant farmers in the 1930s; since the 1940s there has been conflict, which intensified in 1952. By 1955, Britain had suppressed the revolt, and by 1960 Britain accepted the principle of African majority rule. Kenya became independent three years later.[25]

The main period of decolonisation in Africa began after World War II. Growing independence movements, indigenous political parties and trade unions coupled with pressure from within the imperialist powers and from the United States and the Soviet Union ensured the decolonisation of the majority of the continent by 1980. Some areas (in particular South Africa and Namibia) retain a large population of European descent. Only the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla are still governed by a European country. While the islands of Réunion and Mayotte, Saint Helena, Ascension, and Tristan Da Cunha, the Canary Islands and Madeira all remain under either French, British, Spanish, or Portuguese control, the latter two of which were never part of any African polity and have overwhelmingly European populations.

Theoretical frameworks

[edit]The theory of colonialism addresses the problems and consequences of the colonisation of a country, and there has been much research conducted exploring these concepts.

Walter Rodney

[edit]Guyanese historian and activist Walter Rodney proposes in his book How Europe Underdeveloped Africa that Africa was pillaged and plundered by the West through economic exploitation. Using a Marxist analysis, he analyses the modes of resource extraction and systematic underdevelopment of Africa by Europe. He concludes that the structure of present-day Africa and Europe can, through a comparative analysis be traced to the Atlantic slave trade and colonialism. He includes an analysis of gender and states the rights of African women were further diminished during colonialism. [citation needed]

Mahmood Mamdani

[edit]

Mahmood Mamdani wrote his book Citizen and Subject in 1996. The main point of his argument is that the colonial state in Africa took the form of a bifurcated state, "two forms of power under a single hegemonic authority".[26] The colonial state in Africa was divided into two. One state for the colonial European population and one state for the indigenous population. The colonial power was mainly in urban towns and cities and were served by elected governments. The indigenous power was found in rural villages and were ruled by tribal authority, which seemed to be more in keeping with their history and tradition. Mamdani mentions that in urban areas, native institutions were not recognised. The natives, who were portrayed as uncivilised by the Europeans, were excluded from the rights of citizenship.[27] The division of the colonial state created a racial segregation between the European 'citizen' and African 'subject', and a division between institutions of government.

Achille Mbembe

[edit]

Achille Mbembe is a Cameroonian historian, political theorist, and philosopher who has written and theorized extensively on life in the colony and postcolony. His 2000 book On the Postcolony critically examines postcolonial life in Africa and is an important work within the field of postcolonialism. It is through this examination of the postcolony that Mbembe reveals the modes through which power was exerted in colonial Africa. He reminds the reader that colonial powers demanded use of African bodies in particularly violent ways for the purpose of labor as well as the shaping of subservient colonised identities.

By comparing power in the colony and postcolony, Mbembe demonstrates that violence in the colony was exerted on African bodies largely for labor and submission.[28] European colonial powers sought natural resources in African colonies and needed the requisite labor force to extract them and simultaneously build the colonial city around these industries. Because Europeans viewed native bodies as degenerate and in need of taming, violence was necessary to create a submissive laborer.[28] Colonisers viewed this violence as necessary and good because it shaped the African into a productive worker.[28] They had the simultaneous goals of utilizing the raw labor and shaping the identity and character of the African. By beating into the African a docile nature, colonisers ultimately shaped and enforced the way Africans could move through colonial spaces.[28] The African’s day-to-day life then became a show of submission done through exercises like public works projects and military conscription.[28]

Mbembe contrasts colonial violence with that of the postcolony. Mbembe demonstrates that violence in the postcolony is cruder and more generally for the purpose of demonstrating raw power. Expressions of excess and exaggeration characterize this violence.[28] Mbembe's theorization of violence in the colony illuminates the unequal relationship between the coloniser and colonised and reminds us of the violence inflicted on African bodies throughout the process of colonisation. It cannot be understood nor should be taught without the context of this violence.

Stephanie Terreni Brown

[edit]Stephanie Terreni Brown is an academic in the field of colonialism. In her 2014 paper she examines how sanitation and dirt is used in colonial narratives through the example of Kampala.[29] Brown describes abjection as the process whereby one group others or dehumanizes another. Those who are deemed abject are often avoided by others and seen as inferior. Abjectivication is continually used as a mechanism to dominate a group of people and control them. In the case of colonialism, she argues that it is used by the west to dominate over and control the indigenous population of Africa.[29]

Abjectivication through discourses of dirt and sanitation are used to draw distinctions between the Western governing figures and the local population. Dirt being seen as something out of place, whilst cleanliness being attributed to the “in group”, the colonisers, and dirt being paralleled with the indigenous people. The reactions of disgust and displeasure to dirt and uncleanliness are often linked social norms and the wider cultural context, shaping the way in which Africa is still thought of today.[29]

Brown discusses how the colonial authorities were only concerned with constructing a working sewage system to cater for the colonials and were not concerned with the Ugandan population. This rhetoric of sanitation is important because it is seen as a key part of modernity and being civilised. The lack of sanitation and proper sewage systems symbolize that Africans are savages and uncivilised, playing a central role in how the west justified the case of the civilising process. Brown refers to this process of abjectification using discourses of dirt as a physical and material legacy of colonialism that is still very much present in Kampala and other African cities today.[29]

Critique

[edit]Critical theory on the colonisation of Africa is largely unified in a condemnation of imperial activities. Postcolonial theory has been derived from this anti-colonial/anti-imperial concept and writers such as Mbembe, Mamdani and Brown, and many more, have used it as a narrative for their work on the colonisation of Africa.

Post colonialism can be described as a powerful interdisciplinary mood in the social sciences and humanities that is refocusing attention on the imperial/colonial past, and critically revising understanding of the place of the west in the world.[30]

Postcolonial geographers are consistent with the notion that colonialism, although maybe not in such clear-cut forms, is still concurrent today. Both Mbembe, Mamdani and Brown’s theories have a consistent theme of the indigenous Africans having been treated as uncivilised, second class citizens and that in many former colonial cities this has continued into the present day with a switch from race to wealth divide.

On the Postcolony has faced criticism from academics such as Meredith Terreta for focusing too much on specific African nations such as Cameroon.[31] Echoes of this criticism can also be found when looking at the work of Mamdani with his theories questioned for generalising across an Africa that, in reality, was colonised in very different ways, by fundamentally different European imperial ideologies.[32]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Mamdani 1996, p. [page needed].

- ^ Boardman (1973), p. 114

- ^ Boardman (1973), p. 151f

- ^ Boardman (1973), p. 208

- ^ Harden (1971), pp. 163–168

- ^ Scullard (1976), pp. 37, 150, 216

- ^ Adhikari, Mohamed (2017). "Europe's First Settler Colonial Incursion into Africa: The Genocide of Aboriginal Canary Islanders". African Historical Review. 49 (1). Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ Shepperson (1985)

- ^ Khapoya (1998), p. 115f

- ^ "The History of Colonialism in Africa". The Journal of African American History. JSTOR 25610078.

- ^ Bensoussan (2012)

- ^ Khapoya (1998), p. 126f

- ^ Shillington (1995)

- ^ Shillington (1995), p. 340f

- ^ Clay (2016)

- ^ Khapoya (1998), pp. 141–143

- ^ Lovejoy (2012)

- ^ Ferguson (2003)

- ^ "Colonisation of Africa".

- ^ Khapoya (1998), p. 148f

- ^ Khapoya (1998)

- ^ Khapoya (1998), p. 177f

- ^ Shillington (1995), p. 380f

- ^ Khapoya (1998), p. 183

- ^ Shillington (1995), p. 385f

- ^ Mamdani (1996), p. 18

- ^ Mamdani (1996), p. 16

- ^ a b c d e f Mbembe (1992)

- ^ a b c d Brown (2014)

- ^ Clayton (2003)

- ^ Terretta (2002)

- ^ Copans (1998)

References

[edit]- Bensoussan, David (2012). Il était une fois le Maroc - Témoignages du passé judéo-marocain (2nd ed.). iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4759-2609-5.

- Boardman, John (1973) [1964]. The Greeks Overseas. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Brown, Stephanie Terreni (2 January 2014). "Planning Kampala: histories of sanitary intervention and in/formal spaces". Critical African Studies. 6 (1): 71–90. doi:10.1080/21681392.2014.871841. ISSN 2168-1392. S2CID 220331354.

- Clay, Dean (2016). "Transatlantic Dimensions of the Congo Reform Movement, 1904–1908". English Studies in Africa. 59 (1): 18–28. doi:10.1080/00138398.2016.1173274. S2CID 148204694.

- Clayton, Daniel (2003). "Chapter 18: Critical Imperial and Colonial Geographies". In Anderson, Kay; Domosh, Mona; Pile, Steve; Thrift, Nigel (eds.). Handbook of Cultural Geography. Sage London. pp. 354–368. ISBN 9780761969259.

- Copans, Jean (1998). "Review of Citizen and Subject". Transformation. 36: 102–105.

- Ferguson, Niall (2003). Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9615-9.

- Harden, Donald (1971) [1962]. The Phoenicians. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Khapoya, Vincent B. (1998) [1994]. The African Experience (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0137458523.

- Lovejoy, Paul E. (2012). Transformations of Slavery: a History of Slavery in Africa (3rd ed.). London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521176187.

- Mamdani, Mahmood (1996). Citizen and subject : contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism. Kampala: Fountain Publishers. ISBN 9780852553992. OCLC 35445018.

- Mbembe, Achille (1992). "Provisional Notes on the Postcolony". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 62 (1): 3–37. doi:10.2307/1160062. JSTOR 1160062. S2CID 145451482.

- Rodney, Walter (1972). How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. London: Bogle-L'Ouverture. ISBN 978-0-9501546-4-0.

- Scullard, H. H. (1976) [1959]. From the Gracchi to Nero. London: Methuen and Co.

- Shepperson, George (1985). "The Centennial of the West African Conference of Berlin, 1884-1885". Phylon. 4 (1): 37–48. doi:10.2307/274944. JSTOR 274944.

- Shillington, Kevin (1995) [1989]. History of Africa (2nd ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312125981.

- Terretta, Meredith (2002). "Review Work: On the Postcolony by Achille Mbembe". Canadian Journal of African Studies. 36 (1): 161–163.

Further reading

[edit]- Crowther, Michael (1978) [1962]. The Story of Nigeria. London: Faber and Faber.

- Davidson, Basil (1966) [1964]. The African Past. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Gann, Lewis H. Colonialism in Africa, 1870-1960 (1969) Online

- Harris, Norman Dwight (1914). Intervention and Colonization in Africa. Houghton Mifflin.

- Hoskins, H.L. European imperialism in Africa (1967) online

- Michalopoulos, Stelios; Papaioannou, Elias (2020-03-01). "Historical Legacies and African Development." Journal of Economic Literature. 58 (1): 53–128.

- Miers, Suzanne; Klein, Martin A. (1998). Slavery and Colonial Rule in Africa (Slave and Post-Slave Societies and Cultures). Routledge. ISBN 9780714644363.

- Nabudere, D. Wadada. Imperialism in East Africa (2 vol 1981) online

- Olson, James S., ed. Historical Dictionary of the British Empire (1996) Online

- Olson, James S., ed. Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism (1991) online Archived 21 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Pakenham, Thomas (1992). The Scramble for Africa: the White Man's Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912 (13th ed.). London: Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-10449-2.

- Phillips, Anne. The enigma of colonialism : British policy in West Africa (1989) Online

External links

[edit]- Economic Impact of Colonialism

- Germany Refuses to Apologize for Herero Holocaust – from Africana.com

- Andre Osborn, "Belgium exhumes its colonial demons", The Guardian, 12 July 2002

- Blakemore, Erin (6 October 2023). "What is colonialism?". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 8 April 2024. Retrieved 4 June 2024.