Celiac artery

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2018) |

| Celiac artery | |

|---|---|

The celiac artery and its branches. (Celiac artery visible at center.) | |

Surface projections of the major organs of the trunk, showing celiac artery in middle | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Vitelline arteries |

| Source | Abdominal aorta |

| Branches | Left gastric artery common hepatic artery splenic artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | truncus coeliacus, arteria coeliaca |

| MeSH | D002445 |

| TA98 | A12.2.12.012 |

| TA2 | 4211 |

| FMA | 50737 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The celiac (/ˈsiːli.æk/) artery (also spelled coeliac in British English), also known as the celiac trunk or truncus coeliacus, is the first major branch of the abdominal aorta. It is about 1.25 cm in length. Branching from the aorta at thoracic vertebra 12 (T12) in humans, it is one of three anterior/ midline branches of the abdominal aorta (the others are the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries).

Structure

[edit]The celiac artery is the first major branch of the descending abdominal aorta, branching at a 90° angle.[1][2] This occurs just below the crus of the diaphragm.[2] This is around the first lumbar vertebra.[3]

There are three main divisions of the celiac artery, and each in turn has its own named branches:

| Artery | Branches |

|---|---|

| left gastric artery[2] | esophageal branch, stomach branch |

| common hepatic artery[2] | proper hepatic artery, right gastric artery, gastroduodenal artery |

| splenic artery[2] | dorsal pancreatic artery, short gastric arteries, left gastro-omental artery, greater pancreatic artery |

The celiac artery may also give rise to the inferior phrenic arteries.[citation needed]

Function

[edit]The celiac artery supplies oxygenated blood to the liver, stomach, abdominal esophagus, spleen, and the superior half of both the duodenum and the pancreas.[2] These structures correspond to the embryonic foregut. (Similarly, the superior mesenteric artery and inferior mesenteric artery feed structures arising from the embryonic midgut and hindgut respectively. Note that these three anterior branches of the abdominal aorta are distinct and cannot substitute for one another, although there are limited connections between their terminal branches.)

The celiac artery is an essential source of blood, since the interconnections with the other major arteries of the gut are not sufficient to sustain adequate perfusion. Thus it cannot be safely ligated in a living person, and obstruction of the celiac artery will lead to necrosis of the structures it supplies. [citation needed]

Drainage

[edit]The celiac artery is the only major artery that nourishes the abdominal digestive organs that does not have a similarly named vein.

Most blood returning from the digestive organs (including from the area of distribution of the celiac artery) is diverted to the liver via the portal venous system for further processing and detoxification in the liver before returning to the systemic circulation via the hepatic veins.

In contrast to the drainage of midgut and hindgut structures by the superior mesenteric vein and inferior mesenteric vein respectively, venous return from the celiac artery is through either the splenic vein emptying into the hepatic portal vein or via smaller tributaries of the portal venous system.

Clinical significance

[edit]Aneurysms in the celiac artery account for around 4% of visceral artery aneurysms.[4][5] This may cause abdominal pain.[5]

The celiac artery is vulnerable to compression from the crus of the diaphragm during ventilation where it originates from the abdominal aorta.[1] This is known as median arcuate ligament syndrome.[6] This may present no symptoms, but can cause pain due to restricted blood flow to the superior mesenteric artery.[1]

Additional images

[edit]-

Animated volume-rendered CT scan of abdominal and pelvic blood vessels

-

Abdominal part of digestive tube and its attachment to the primitive or common mesentery; human embryo at six weeks

-

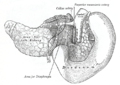

The pancreas and duodenum from behind

-

Arteries and veins around the pancreas and spleen

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Williams, Timothy K.; Harthun, Nancy; Machleder, Herbert I.; Freischlag, Julie Ann (2013-01-01), Creager, Mark A.; Beckman, Joshua A.; Loscalzo, Joseph (eds.), "Chapter 62 - Vascular Compression Syndromes", Vascular Medicine: A Companion to Braunwald's Heart Disease (Second Edition), Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, pp. 755–770, ISBN 978-1-4377-2930-6, retrieved 2021-01-13

- ^ a b c d e f Chiva, Luis M.; Magrina, Javier (2018-01-01), Ramirez, Pedro T.; Frumovitz, Michael; Abu-Rustum, Nadeem R. (eds.), "Chapter 2 - Abdominal and Pelvic Anatomy", Principles of Gynecologic Oncology Surgery, Elsevier, pp. 3–49, ISBN 978-0-323-42878-1, retrieved 2021-01-13

- ^ Paterson-Brown, Sara (2010-01-01), Bennett, Phillip; Williamson, Catherine (eds.), "Chapter Five - Applied anatomy", Basic Science in Obstetrics and Gynaecology (Fourth Edition), Churchill Livingstone, pp. 57–95, ISBN 978-0-443-10281-3, retrieved 2021-01-13

- ^ Reil, Todd D.; Gevorgyan, Alexander; Jimenez, Juan Carlos; Ahn, Samuel S. (2011-01-01), Moore, Wesley S.; Ahn, Samuel S. (eds.), "Chapter 49 - Endovascular Treatment of Visceral Artery Aneurysms", Endovascular Surgery (Fourth Edition), Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, pp. 521–527, ISBN 978-1-4160-6208-0, retrieved 2021-01-13

- ^ a b Rectenwald, John E.; Stanley, James C.; Upchurch, Gilbert R. (2009-01-01), Hallett, John W.; Mills, Joseph L.; Earnshaw, Jonothan J.; Reekers, Jim A. (eds.), "chapter 21 - Splanchnic Artery Aneurysms", Comprehensive Vascular and Endovascular Surgery (Second Edition), Philadelphia: Mosby, pp. 358–370, ISBN 978-0-323-05726-4, retrieved 2021-01-13

- ^ Cutsforth-Gregory, Jeremy K.; Sandroni, Paola (2019-01-01), Levin, Kerry H.; Chauvel, Patrick (eds.), "Chapter 29 - Clinical neurophysiology of postural tachycardia syndrome", Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Clinical Neurophysiology: Diseases and Disorders, 161, Elsevier: 429–445, doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-64142-7.00066-7, ISBN 9780444641427, PMID 31307619, S2CID 196813489, retrieved 2021-01-13

External links

[edit]- Anatomy figure: 38:01-09 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Branches of the celiac trunk."

- Anatomy figure: 40:05-01 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Parietal and visceral branches of the abdominal aorta."

- celiactrunk at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)

- MedEd at Loyola Radio/curriculum/Vascular/hema144A.jpg