Coca-Cola

Logo used since 1946 | |

Coca-Cola has retained many of its historical design features in modern glass bottles. | |

| Type | Cola |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | The Coca-Cola Company |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Region of origin | Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Introduced | May 8, 1886 |

| Color | Caramel E-150d |

| Variants | |

| Related products | Mojo Pepsi RC Cola Afri-Cola Postobón Inca Kola Kola Real Cavan Cola Est Cola |

| Website | coca-cola.com |

Coca-Cola, or Coke, is a cola soft drink manufactured by the Coca-Cola Company. In 2013, Coke products were sold in over 200 countries and territories worldwide, with consumers drinking more than 1.8 billion company beverage servings each day.[1] Coca-Cola ranked No. 94 in the 2024 Fortune 500 list of the largest United States corporations by revenue.[2] Based on Interbrand's "best global brand" study of 2023, Coca-Cola was the world's sixth most valuable brand.[3]

Originally marketed as a temperance drink and intended as a patent medicine, Coca-Cola was invented in the late 19th century by John Stith Pemberton in Atlanta, Georgia. In 1888, Pemberton sold the ownership rights to Asa Griggs Candler, a businessman, whose marketing tactics led Coca-Cola to its dominance of the global soft-drink market throughout the 20th and 21st century.[4] The name refers to two of its original ingredients: coca leaves and kola nuts (a source of caffeine).[5] The formula of Coca-Cola remains a trade secret; however, a variety of reported recipes and experimental recreations have been published. The secrecy around the formula has been used by Coca-Cola as a marketing aid because only a handful of anonymous employees know the formula.[6] The drink has inspired imitators and created a whole classification of soft drink: colas.

The Coca-Cola Company produces concentrate, which is then sold to licensed Coca-Cola bottlers throughout the world. The bottlers, who hold exclusive territory contracts with the company, produce the finished product in cans and bottles from the concentrate, in combination with filtered water and sweeteners. A typical 12-US-fluid-ounce (350 ml) can contains 38 grams (1.3 oz) of sugar (usually in the form of high-fructose corn syrup in North America). The bottlers then sell, distribute, and merchandise Coca-Cola to retail stores, restaurants, and vending machines throughout the world. The Coca-Cola Company also sells concentrate for soda fountains of major restaurants and foodservice distributors.

The Coca-Cola Company has on occasion introduced other cola drinks under the Coke name. The most common of these is Diet Coke, along with others including Caffeine-Free Coca-Cola, Diet Coke Caffeine-Free, Coca-Cola Zero Sugar, Coca-Cola Cherry, Coca-Cola Vanilla, and special versions with lemon, lime, and coffee. Coca-Cola was called "Coca-Cola Classic" from July 1985 to 2009, to distinguish it from "New Coke".

History

19th century origins

Confederate Colonel John Pemberton, wounded in the American Civil War and addicted to morphine, also had a medical degree and began a quest to find a substitute for the problematic drug.[8] In 1885 at Pemberton's Eagle Drug and Chemical House, his drugstore in Columbus, Georgia, he registered Pemberton's French Wine Coca nerve tonic.[9][10][11][12] Pemberton's tonic may have been inspired by the formidable success of Vin Mariani, a French-Corsican coca wine,[13] but his recipe additionally included the African kola nut, the beverage's source of caffeine.[14] A Spanish drink called "Kola Coca" was presented at a contest in Philadelphia in 1885, a year before the official birth of Coca-Cola. The rights for this Spanish drink were bought by Coca-Cola in 1953.[15][16]

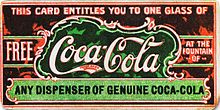

In 1886, when Atlanta and Fulton County passed prohibition legislation, Pemberton responded by developing Coca-Cola, a non-alcoholic version of Pemberton's French Wine Coca.[17] It was marketed as "Coca-Cola: The temperance drink", which appealed to many people as the temperance movement enjoyed wide support during this time.[4] The first sales were at Jacob's Pharmacy in Atlanta, Georgia, on May 8, 1886,[18] where it initially sold for five cents a glass.[19] Drugstore soda fountains were popular in the United States at the time due to the belief that carbonated water was good for the health,[20] and Pemberton's new drink was marketed and sold as a patent medicine, Pemberton claiming it a cure for many diseases, including morphine addiction, indigestion, nerve disorders, headaches, and impotence. Pemberton ran the first advertisement for the beverage on May 29 of the same year in the Atlanta Journal.[21]

By 1888, three versions of Coca-Cola – sold by three separate businesses – were on the market. A co-partnership had been formed on January 14, 1888, between Pemberton and four Atlanta businessmen: J.C. Mayfield, A.O. Murphey, C.O. Mullahy, and E.H. Bloodworth. Not codified by any signed document, a verbal statement given by Asa Candler years later asserted under testimony that he had acquired a stake in Pemberton's company as early as 1887.[22] John Pemberton declared that the name "Coca-Cola" belonged to his son, Charley, but the other two manufacturers could continue to use the formula.[23]

Charley Pemberton's record of control over the "Coca-Cola" name was the underlying factor that allowed for him to participate as a major shareholder in the March 1888 Coca-Cola Company incorporation filing made in his father's place.[24] Charley's exclusive control over the "Coca-Cola" name became a continual thorn in Asa Candler's side. Candler's oldest son, Charles Howard Candler, authored a book in 1950 published by Emory University. In this definitive biography about his father, Candler specifically states: "on April 14, 1888, the young druggist Asa Griggs Candler purchased a one-third interest in the formula of an almost completely unknown proprietary elixir known as Coca-Cola."[25] The deal was actually between John Pemberton's son Charley and Walker, Candler & Co. – with John Pemberton acting as cosigner for his son. For $50 down and $500 in 30 days, Walker, Candler & Co. obtained all of the one-third interest in the Coca-Cola Company that Charley held, all while Charley still held on to the name. After the April 14 deal, on April 17, 1888, one-half of the Walker/Dozier interest shares were acquired by Candler for an additional $750.[26]

Company

After Candler had gained a better foothold on Coca-Cola in April 1888, he nevertheless was forced to sell the beverage he produced with the recipe he had under the names "Yum Yum" and "Koke". This was while Charley Pemberton was selling the elixir, although a cruder mixture, under the name "Coca-Cola", all with his father's blessing. After both names failed to catch on for Candler, by the middle of 1888, the Atlanta pharmacist was quite anxious to establish a firmer legal claim to Coca-Cola, and hoped he could force his two competitors, Walker and Dozier, completely out of the business, as well.[26]

John Pemberton died suddenly on August 16, 1888. Asa Candler then decided to move swiftly forward to attain full control of the entire Coca-Cola operation.

Charley Pemberton, an alcoholic and opium addict, unnerved Asa Candler more than anyone else. Candler is said to have quickly maneuvered to purchase the exclusive rights to the name "Coca-Cola" from Pemberton's son Charley immediately after he learned of Dr. Pemberton's death. One of several stories states that Candler approached Charley's mother at John Pemberton's funeral and offered her $300 in cash for the rights to the name.

In Charles Howard Candler's 1950 book about his father, he stated: "On August 30 [1888], he [Asa Candler] became the sole proprietor of Coca-Cola, a fact which was stated on letterheads, invoice blanks and advertising copy."[25]

With this action on August 30, 1888, Candler's sole control became technically all true. Candler had negotiated with Margaret Dozier and her brother Woolfolk Walker a full payment amounting to $1,000, which all agreed Candler could pay off with a series of notes over a specified time span. By May 1, 1889, Candler was claiming full ownership of the Coca-Cola beverage, with a total investment outlay by Candler for the drink enterprise over the years amounting to $2,300.[27]

In 1914, Margaret Dozier, as co-owner of the original Coca-Cola Company in 1888, came forward to claim that her signature on the 1888 Coca-Cola Company bill of sale had been forged. Subsequent analysis of other similar transfer documents had also indicated John Pemberton's signature had most likely been forged as well, which some accounts claim was precipitated by his son Charley.[23]

In 1892, Candler set out to incorporate a second company, the Coca-Cola Company (the modern corporation). When Candler had the earliest records of the "Coca-Cola Company" destroyed in 1910, the action was claimed to have been made during a move to new corporation offices around this time.[28]

On June 23, 1894, Charley Pemberton was found unconscious with a stick of opium by his side. Ten days later, Charley died at Atlanta's Grady Hospital at the age of 40.[29]

On September 12, 1919, Coca-Cola Co. was purchased by a group of investors led by Ernest Woodruff's Trust Company for $25 million and reincorporated under the Delaware General Corporation Law. The company publicly offered 500,000 shares of the company for $40 a share.[30][31] In 1923, his son Robert W. Woodruff was elected President of the company. Woodruff expanded the company and brought Coca-Cola to the rest of the world. Coca-Cola began distributing bottles as "Six-packs", encouraging customers to purchase the beverage for their home.[32]

During its first several decades, Coca-Cola officially wanted to be known by its full-name despite being commonly known as "Coke". This was due to company fears that the term "coke" would eventually become a generic trademark, which to an extent became true in the Southern United States where "coke" is used even for non Coca-Cola products. The company also didn't want to confuse its drink with the similarly named coal byproduct that clearly wasn't safe to consume. Eventually, out for fears that another company may claim the trademark for "Coke", Coca-Cola finally embraced it and officially endorsed the name "Coke" in 1941. "Coke" eventually became a registered trademark of the Coca-Cola Company in 1945.[33]

In 1986, the Coca-Cola Company merged with two of their bottling operators (owned by JTL Corporation and BCI Holding Corporation) to form Coca-Cola Enterprises Inc. (CCE).[34]

In December 1991, Coca-Cola Enterprises merged with the Johnston Coca-Cola Bottling Group, Inc.[34]

Origins of bottling

The first bottling of Coca-Cola occurred in Vicksburg, Mississippi, at the Biedenharn Candy Company on March 12, 1894.[35] The proprietor of the bottling works was Joseph A. Biedenharn.[36] The original bottles were Hutchinson bottles, very different from the much later hobble-skirt design of 1915 now so familiar.

A few years later two entrepreneurs from Chattanooga, Tennessee, namely Benjamin F. Thomas and Joseph B. Whitehead, proposed the idea of bottling and were so persuasive that Candler signed a contract giving them control of the procedure for only one dollar. Candler later realized that he had made a grave mistake.[37] Candler never collected his dollar, but in 1899, Chattanooga became the site of the first Coca-Cola bottling company. Candler remained very content just selling his company's syrup.[38] The loosely termed contract proved to be problematic for the Coca-Cola Company for decades to come. Legal matters were not helped by the decision of the bottlers to subcontract to other companies, effectively becoming parent bottlers.[39] This contract specified that bottles would be sold at 5¢ each and had no fixed duration, leading to the fixed price of Coca-Cola from 1886 to 1959.

20th century

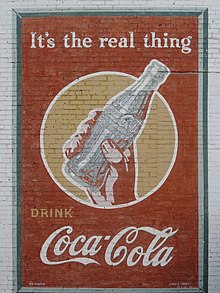

The first outdoor wall advertisement that promoted the Coca-Cola drink was painted in 1894 in Cartersville, Georgia.[40] Cola syrup was sold as an over-the-counter dietary supplement for upset stomach.[41][42] By the time of its 50th anniversary, the soft drink had reached the status of a national icon in the US. In 1935, it was certified kosher by Atlanta rabbi Tobias Geffen. With the help of Harold Hirsch, Geffen was the first person outside the company to see the top-secret ingredients list after Coke faced scrutiny from the American Jewish population regarding the drink's kosher status.[43] Consequently, the company made minor changes in the sourcing of some ingredients so it could continue to be consumed by America's Jewish population, including during Passover.[44] A yellow cap on a Coca-Cola drink indicates that it is kosher for Passover.[45]

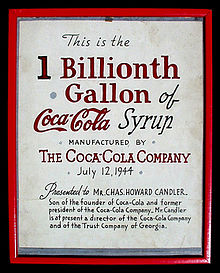

The longest running commercial Coca-Cola soda fountain anywhere was Atlanta's Fleeman's Pharmacy, which first opened its doors in 1914.[46] Jack Fleeman took over the pharmacy from his father and ran it until 1995; closing it after 81 years.[47] On July 12, 1944, the one-billionth gallon of Coca-Cola syrup was manufactured by the Coca-Cola Company. Cans of Coke first appeared in 1955.[48]

Sugar replaced with high-fructose corn syrup

Sugar prices spiked in the 1970s because of Soviet demand/hoarding and possible futures contracts market manipulation. The Soviet Union was the largest producer of sugar at the time. In 1974 Coca-Cola switched over to high-fructose corn syrup because of the elevated prices.[49][50]

New Coke

On April 23, 1985, Coca-Cola, amid much publicity, attempted to change the formula of the drink with "New Coke". Follow-up taste tests revealed most consumers preferred the taste of New Coke to both old Coke and Pepsi[51] but Coca-Cola management was unprepared for the public's nostalgia for the old drink, leading to a backlash. The company gave in to protests and returned to the old formula under the name Coca-Cola Classic, on July 10, 1985. "New Coke" remained available and was renamed Coke II in 1992; it was discontinued in 2002.

21st century

On July 5, 2005, it was revealed that Coca-Cola would resume operations in Iraq for the first time since the Arab League boycotted the company in 1968.[52]

In April 2007, in Canada, the name "Coca-Cola Classic" was changed back to "Coca-Cola". The word "Classic" was removed because "New Coke" was no longer in production, eliminating the need to differentiate between the two.[53] The formula remained unchanged. In January 2009, Coca-Cola stopped printing the word "Classic" on the labels of 16-US-fluid-ounce (470 ml) bottles sold in parts of the southeastern United States.[54] The change was part of a larger strategy to rejuvenate the product's image.[54] The word "Classic" was removed from all Coca-Cola products by 2011.

In November 2009, due to a dispute over wholesale prices of Coca-Cola products, Costco stopped restocking its shelves with Coke and Diet Coke for two months; a separate pouring rights deal in 2013 saw Coke products removed from Costco food courts in favor of Pepsi.[55] Some Costco locations (such as the ones in Tucson, Arizona) additionally sell imported Coca-Cola from Mexico with cane sugar instead of corn syrup from separate distributors.[56] Coca-Cola introduced the 7.5-ounce mini-can in 2009, and on September 22, 2011, the company announced price reductions, asking retailers to sell eight-packs for $2.99. That same day, Coca-Cola announced the 12.5-ounce bottle, to sell for 89 cents. A 16-ounce bottle has sold well at 99 cents since being re-introduced, but the price was going up to $1.19.[57]

In 2012, Coca-Cola resumed business in Myanmar after 60 years of absence due to US-imposed investment sanctions against the country.[58][59] Coca-Cola's bottling plant is located in Yangon and is part of the company's five-year plan and $200 million investment in Myanmar.[60] Coca-Cola with its partners is to invest US$5 billion in its operations in India by 2020.[61]

In February 2021, as a plan to combat plastic waste, Coca-Cola said that it would start selling its sodas in bottles made from 100% recycled plastic material in the United States, and by 2030 planned to recycle one bottle or can for each one it sold.[62] Coca-Cola started by selling 2000 paper bottles to see if they held up due to the risk of safety and of changing the taste of the drink.[63]

Production

Listed ingredients

- Carbonated water

- Sugar (sucrose or high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) depending on country of origin)

- Caffeine

- Phosphoric acid

- Caramel color (E150d)

- Natural flavorings[64]

A typical can of Coca-Cola (12 fl ounces/355 ml) contains 39 grams of sugar,[65] 46 mg of caffeine,[66] 50 mg of sodium, no fat, no potassium, and 140 calories.[67]

Formula of natural flavorings

The exact formula for Coca-Cola's natural flavorings is a trade secret. (All of its other ingredients are listed on the side of the bottle or can, and are not secret.) The original copy of the formula was held in Truist Financial's main vault in Atlanta for 86 years. Its predecessor, the Trust Company, was the underwriter for the Coca-Cola Company's initial public offering in 1919. On December 8, 2011, the original secret formula was moved from the vault at SunTrust Banks into a new vault; this vault will be on display for visitors to its World of Coca-Cola museum in downtown Atlanta.[68]

According to Snopes, a popular myth states that only two executives have access to the formula, with each executive having only half the formula.[69] However, several sources state that while Coca-Cola does have a rule restricting access to only two executives, each of them knows the entire formula, and that persons other than the prescribed duo have known the formulation process.[70]

On February 11, 2011, Ira Glass said on his PRI radio show, This American Life, that his staffers had found a recipe in "Everett Beal's Recipe Book", reproduced in the February 28, 1979 issue of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, that they believed was either Pemberton's original formula for Coca-Cola or a version that he made either before or after the product hit the market in 1886. The formula basically matched the one found in Pemberton's diary.[71][72][73] Coca-Cola archivist Phil Mooney acknowledged that the recipe "could be a precursor" to the formula used in the original 1886 product, but emphasized that Pemberton's original formula is not the same as the one used in the modern product.[74]

Use of stimulants in formula

When launched, Coca-Cola's two key ingredients were cocaine and caffeine. The cocaine was derived from the coca leaf and the caffeine from kola nut (also spelled "cola nut" at the time), leading to the name Coca-Cola.[75][76]

Coca leaf

Pemberton called for five ounces of coca leaf per gallon of syrup (approximately 37 g/L), a significant dose; in 1891, Candler claimed his formula (altered extensively from Pemberton's original) contained only a tenth of this amount. Coca-Cola once contained an estimated nine milligrams of cocaine per glass. (For comparison, a typical dose or "line" of cocaine is 50–75 mg.[77]) In 1903, the fresh coca leaves were removed from the formula.[78]

After 1904, instead of using fresh leaves, Coca-Cola started using "spent" leaves – the leftovers of the cocaine-extraction process with trace levels of cocaine.[79] Since then (by 1929[80]), Coca-Cola has used a cocaine-free coca leaf extract. Today, that extract is prepared at a Stepan Company plant in Maywood, New Jersey, the only manufacturing plant authorized by the federal government to import and process coca leaves, which it obtains from Peru and Bolivia.[81] Stepan Company extracts cocaine from the coca leaves, which it then sells to Mallinckrodt, the only company in the United States licensed to purify cocaine for medicinal use.[82]

Long after the syrup had ceased to contain any significant amount of cocaine, in North Carolina "dope" remained a common colloquialism for Coca-Cola, and "dope-wagons" were trucks that transported it.[83]

Kola nuts for caffeine

The kola nut acts as a flavoring and the original source of caffeine in Coca-Cola. It contains about 2.0 to 3.5% caffeine, and has a bitter flavor.

In 1911, the US government sued in United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola, hoping to force the Coca-Cola Company to remove caffeine from its formula. The court found that the syrup, when diluted as directed, would result in a beverage containing 1.21 grains (or 78.4 mg) of caffeine per 8 US fluid ounces (240 ml) serving.[84] The case was decided in favor of the Coca-Cola Company at the district court, but subsequently in 1912, the US Pure Food and Drug Act was amended, adding caffeine to the list of "habit-forming" and "deleterious" substances which must be listed on a product's label. In 1913 the case was appealed to the Sixth Circuit in Cincinnati, where the ruling was affirmed, but then appealed again in 1916 to the Supreme Court, where the government effectively won as a new trial was ordered. The company then voluntarily reduced the amount of caffeine in its product, and offered to pay the government's legal costs to settle and avoid further litigation.

Coca-Cola contains 46 mg of caffeine per 12 US fluid ounces (or 30.7 mg per 8 US fluid ounces (240 ml) serving).[66]

Franchised production model

The production and distribution of Coca-Cola follows a franchising model. The Coca-Cola Company only produces a syrup concentrate, which it sells to bottlers throughout the world, who hold Coca-Cola franchises for one or more geographical areas. The bottlers produce the final drink by mixing the syrup with filtered water and sweeteners, putting the mixture into cans and bottles, and carbonating it, which the bottlers then sell and distribute to retail stores, vending machines, restaurants, and foodservice distributors.[85]

The Coca-Cola Company owns minority shares in some of its largest franchises, such as Coca-Cola Enterprises, Coca-Cola Amatil, Coca-Cola Hellenic Bottling Company, and Coca-Cola FEMSA, as well as some smaller ones, such as Coca-Cola Bottlers Uzbekistan, but fully independent bottlers produce almost half of the volume sold in the world. Independent bottlers are allowed to sweeten the drink according to local tastes.[86]

Geographic spread

Coca-Cola has been sold outside the United States as early as 1900, when the Cuba Libre (a mix between Coca-Cola and rum) was created in Havana shortly after the Spanish-American War of 1898. However, the international reach of the product became mostly limited to North and Central America, the Caribbean, the Netherlands, Germany and parts of Asia until the 1940s, when the brand was introduced throughout South America and then Europe after the end of World War II (Fanta was initially conceived by the German Coca-Cola subsidiary as an emergency replacement as the wartime trade embargo prevented the import of syrup). As a result, Coca-Cola eventually became regarded as one of the major symbols of American soft power as well as of globalization.

Since it announced its intention to begin distribution in Myanmar in June 2012, Coca-Cola has been officially available in every country in the world except Cuba (where it stopped being available officially since 1960—ironically, Coca-Cola's first bottling plant outside the United States was established there in 1906) and North Korea.[87] However, it is reported to be available in both countries as a grey import.[88][89] As of 2022, Coca-Cola has suspended its operations in Russia due to the invasion of Ukraine.[90]

Coca-Cola has been a point of legal discussion in the Middle East. In the early 20th century, a fatwa was created in Egypt to discuss the question of "whether Muslims were permitted to drink Coca-Cola and Pepsi cola."[91] The fatwa states: "According to the Muslim Hanefite, Shafi'ite, etc., the rule in Islamic law of forbidding or allowing foods and beverages is based on the presumption that such things are permitted unless it can be shown that they are forbidden on the basis of the Qur'an."[91] The Muslim jurists stated that, unless the Qur'an specifically prohibits the consumption of a particular product, it is permissible to consume. Another clause was discussed, whereby the same rules apply if a person is unaware of the condition or ingredients of the item in question.

Coca-Cola first entered the Chinese market in the 1920s with no localized representation of its name.[92][93] While the company researched a satisfactory translation, local shopkeepers created their own. These produced the desired "ko-ka ko-la" sound, but with odd meanings such as "female horse fastened with wax" or "bite the wax tadpole".[92][93] In the 1930s, the company settled on the name "可口可樂(可口可乐)" (Ke-kou ke-le) taking into account the effects of syllable and meaning translations. The phrase means roughly "to allow the mouth to be able to rejoice".[93][94] The story introduction from Coca-Cola mentions that Chiang Yee provided the new localized name,[95] but there are also sources that the localized name appeared before 1935,[96] or that it was given by someone named Jerome T. Lieu who studied at Columbia University in New York.[97]

Brand portfolio

This is a list of variants of Coca-Cola introduced around the world. In addition to the caffeine-free version of the original, additional fruit flavors have been included over the years. Not included here are versions of Diet Coke and Coca-Cola Zero Sugar; these variant versions of those no-calorie colas can be found in their respective articles.

| Name | Launched | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Diet Coke | 1983 | A low-calorie version of Coca-Cola with sweeteners instead of sugar or corn syrup. |

| Caffeine-Free Coca-Cola | 1983 | A variant of the standard Coca-Cola without caffeine.[citation needed] |

| Coca-Cola Cherry | 1985 | Coca-Cola with a cherry flavor. It was originally marketed as Cherry Coke (Cherry Coca-Cola), and was named as such in North America until 2006.[citation needed] |

| New Coke / Coca-Cola II | 1985 | An unpopular formula change, remained after the original formula quickly returned and was later rebranded as Coca-Cola II until its full discontinuation in 2002. In 2019, New Coke was re-introduced to the market to promote the third season of the Netflix original series, Stranger Things.[98] |

| Golden Coca-Cola | 2001 | A limited edition produced by Beijing Coca-Cola company to celebrate Beijing's successful bid to host the Olympics.[citation needed] |

| Coca-Cola Vanilla | 2002 | Coca-Cola with a vanilla flavor. |

| Coca-Cola C2 | 2004 | A mid-calorie version of Coca-Cola sweetened with both corn syrup and artificial sweeteners. It was first sold in Japan, and shortly expanded to North America. The drink was a flop, and was commonly replaced with Coca-Cola Zero upon its launch until it was fully discontinued in 2007. |

| Coca-Cola with Lime | 2005 | Coca-Cola with a lime flavor, introduced after the success of its diet counterpart. |

| Coca-Cola with Lemon | 2005 | Coca-Cola with a lemon flavor. Debuted in the United Kingdom, and was also available in Japan, France, Hong Kong, Brazil, and Hungary. |

| Coca-Cola Raspberry | 2005 | Coca-Cola with a raspberry flavor. It was originally exclusively sold in New Zealand for a short time and was later given a wider international release through the Coca-Cola Freestyle fountain machine. |

| Coca-Cola Zero/Coca-Cola Zero Sugar | 2005 | Low-calorie variant formulated to be more like standard Coca-Cola. It has had different formula changes over the years. |

| Coca-Cola Citra | 2005 | Coca-Cola with a Lemon-Lime flavor. It was first sold as a limited edition in Mexico and New Zealand, before gaining a release in Japan. |

| Coca-Cola Black Cherry Vanilla | 2006 | Coca-Cola with a combination of black cherry and vanilla flavor. It was only sold in North America as a replacement to Vanilla Coke, before the drink returned and re-replaced it in June 2007. |

| Coca-Cola Blāk | 2006 | Coca-Cola with a rich coffee flavor, of which the formula depends on the country. It was first sold in France, before being released in North America where it was discontinued in 2008. |

| Coca-Cola Orange | 2007 | Coca-Cola with an orange flavor, similar to that of the drink Mezzo Mix which is sold in DACH regions. It was available in the United Kingdom and Gibraltar as a limited edition for the summer of 2007. It was later given a wider international release through the Coca-Cola Freestyle fountain machine. |

| Coca-Cola Life | 2014 | A version of Coca-Cola with stevia and sugar as sweeteners rather than simply sugar. It was largely unsuccessful and was quietly discontinued in all territories by 2020. |

| Coca-Cola Ginger | 2016 | A version that mixes in the classic Coca-Cola formula with the taste of ginger beer. It was available as a limited edition in Vietnam, Australia, and New Zealand. |

| Coca-Cola Fiber+ | 2017 | A dietary variant of Coca-Cola with added dietary fiber in the form of dextrin developed by Coca-Cola Asia Pacific. It is available in Asian territories such as Japan, Taiwan, mainland China, Hong Kong, Vietnam, and Mongolia. |

| Coca-Cola with Coffee | 2017 | Coca-Cola mixed in with Coffee. It was originally introduced in Japan in 2017 before expanding to North America in January 2021, available in Dark Blend, Vanilla and Caramel variants along with Zero Sugar dark blend and vanilla variants. The North American unit was discontinued the following year.[99] |

| Coca-Cola Peach | 2018 | Coca-Cola with a Peach flavor. It was made for and sold exclusively in Japan as a limited edition in 2018[100] and 2019[101] and later sold in China. |

| Coca-Cola Georgia Peach | 2018 | A hand-crafted Peach-flavored Coca-Cola sweetened with cane sugar. Sold in the United States.[102] |

| Coca-Cola California Raspberry | 2018 | A hand-crafted Raspberry-flavored Coca-Cola sweetened with cane sugar. Sold in the United States.[102] |

| Coca-Cola Orange Vanilla | 2019 | Coca-Cola with an orange vanilla flavor, intended to imitate the flavor of an orange Creamsicle. It was available nationwide in the United States on February 25, 2019.[103] and was discontinued in 2021. |

| Coca-Cola Energy | 2019 | An energy drink with a flavor similar to standard Coca-Cola, with guarana, vitamin B3 (niacinamide), vitamin B6 (pyridoxine hydrochloride), and extra caffeine. The drink debuted in Spain and Hungary in April 2019[104] and would go onto launch in Australia, the United Kingdom[105] and other European territories throughout the year. The drink debuted in North America in 2020[106] and was largely unsuccessful, with Coca-Cola announcing its discontinuation in the latter market in May 2021, to focus more on its traditional beverages.[107] |

| Coca-Cola Signature Mixers | 2019 | Premium variants of the original Coca-Cola formula that were made to blend in with different dark spirits. It was sold in Smokey, Spicy, Herbal and Woody varieties.[108] They were sold in the United Kingdom from 2019 until 2022.[109] |

| Coca-Cola Apple | 2019 | Coca-Cola with an Apple flavor. Sold in Japan for a limited time in 2019[110] and was also made available in Hong Kong. |

| Coca-Cola Cinnamon | 2019 | Coca-Cola with cinnamon flavor. Released in October 2019 in the United States as a limited release for the 2019 holiday season.[111] Made available again in 2020 for the holiday season. |

| Coca-Cola Strawberry | 2020 | Coca-Cola with a Strawberry flavor. Sold in Japan for a limited time in 2020[112] and later sold in China. |

| Coca-Cola Cherry Vanilla | 2020 | Coca-Cola with cherry vanilla flavor. Released in the United States on February 10, 2020. |

| Coca-Cola Energy Cherry | 2020 | Cherry-flavored variant of the standard Coca-Cola Energy. Debuted in North America in January 2020[113] and the United Kingdom in April.[114] |

| Coca-Cola Creations | 2022 | Limited edition variants of the original Coca-Cola formula that were made to appeal to younger consumers,[115][116] such as Coca-Cola Starlight[117] and Coca-Cola Ultimate.[118] They has been sold internationally as well. |

| Jack Daniel's and Coca-Cola | 2022 | A ready-to-drink canned mixture of Tennessee whiskey and Coca-Cola. Debuted in Mexico in November 2022, and expanded to the United Kingdom and North America in March 2023,[119][120] before expanding to other European territories, Asia and Latin America. |

| Coca-Cola Spiced | 2024 | Coca-Cola with a Raspberry and spiced flavoring. It was sold in the United States and Canada from February[121] until September 2024.[122] |

Logo design

The Coca-Cola logo was created by John Pemberton's bookkeeper, Frank Mason Robinson, in 1885.[123] Robinson came up with the name and chose the logo's distinctive cursive script. The writing style used, known as Spencerian script, was developed in the mid-19th century and was the dominant form of formal handwriting in the United States during that period.[124]

Robinson also played a significant role in early Coca-Cola advertising. His promotional suggestions to Pemberton included giving away thousands of free drink coupons and plastering the city of Atlanta with publicity banners and streetcar signs.[125]

Coca-Cola came under scrutiny in Egypt in 1951 because of a conspiracy theory that the Coca-Cola logo, when reflected in a mirror, spells out "No Mohammed no Mecca" in Arabic.[126][127]

Contour bottle design

The Coca-Cola bottle, called the "contour bottle" within the company, was created by bottle designer Earl R. Dean and Coca-Cola's general counsel, Harold Hirsch. In 1915, the Coca-Cola Company was represented by their general counsel to launch a competition among its bottle suppliers as well as any competition entrants to create a new bottle for their beverage that would distinguish it from other beverage bottles, "a bottle which a person could recognize even if they felt it in the dark, and so shaped that, even if broken, a person could tell at a glance what it was."[128][129][130][131]

Chapman J. Root, president of The Root Glass Company of Terre Haute, Indiana, turned the project over to members of his supervisory staff, including company auditor T. Clyde Edwards, plant superintendent Alexander Samuelsson, and Earl R. Dean, bottle designer and supervisor of the bottle molding room. Root and his subordinates decided to base the bottle's design on one of the soda's two ingredients, the coca leaf or the kola nut, but were unaware of what either ingredient looked like. Dean and Edwards went to the Emeline Fairbanks Memorial Library and were unable to find any information about coca or kola. Instead, Dean was inspired by a picture of the gourd-shaped cocoa pod in the Encyclopædia Britannica. Dean made a rough sketch of the pod and returned to the plant to show Root. He explained to Root how he could transform the shape of the pod into a bottle. Root gave Dean his approval.[128]

Faced with the upcoming scheduled maintenance of the mold-making machinery, over the next 24 hours Dean sketched out a concept drawing which was approved by Root the next morning. Chapman Root approved the prototype bottle and a design patent was issued on the bottle in November 1915. The prototype never made it to production since its middle diameter was larger than its base, making it unstable on conveyor belts. Dean resolved this issue by decreasing the bottle's middle diameter. During the 1916 bottler's convention, Dean's contour bottle was chosen over other entries and was on the market the same year. By 1920, the contour bottle became the standard for the Coca-Cola Company. A revised version was also patented in 1923. Because the Patent Office releases the Patent Gazette on Tuesday, the bottle was patented on December 25, 1923, and was nicknamed the "Christmas bottle". Today, the contour Coca-Cola bottle is one of the most recognized packages on the planet.[39]

As a reward for his efforts, Dean was offered a choice between a $500 bonus or a lifetime job at The Root Glass Company. He chose the lifetime job and kept it until the Owens-Illinois Glass Company bought out The Root Glass Company in the mid-1930s. Dean went on to work in other Midwestern glass factories.[132]

Raymond Loewy updated the design in 1955 to accommodate larger formats.[133] Misinterpretations of comments Loewy made on his involvement have given rise to a popular misconception, misattributing him as the original designer of the coke bottle.[134][135]

Others have attributed inspiration for the design not to the cocoa pod, but to a Victorian hooped dress.[136]

In 1944, Associate Justice Roger J. Traynor of the Supreme Court of California took advantage of a case involving a waitress injured by an exploding Coca-Cola bottle to articulate the doctrine of strict liability for defective products. Traynor's concurring opinion in Escola v. Coca-Cola Bottling Co. is widely recognized as a landmark case in US law today.[137][138][139][140][141]

Examples

-

Earl R. Dean's original 1915 concept drawing of the contour Coca-Cola bottle

-

The prototype never made it to production since its middle diameter was larger than its base, making it unstable on conveyor belts.

-

Final production version with slimmer middle section

-

Numerous historical Coke bottles

Designer bottles

Karl Lagerfeld is the latest designer to have created a collection of aluminum bottles for Coca-Cola. Lagerfeld is not the first fashion designer to create a special version of the famous Coca-Cola Contour bottle. A number of other limited edition bottles by fashion designers for Coca-Cola Light soda have been created in the last few years, including Jean Paul Gaultier.[142]

In 2009, in Italy, Coca-Cola Light had a Tribute to Fashion to celebrate 100 years of the recognizable contour bottle. Well known Italian designers Alberta Ferretti, Blumarine, Etro, Fendi, Marni, Missoni, Moschino, and Versace each designed limited edition bottles.[143]

In 2019, Coca-Cola shared the first beverage bottle made with ocean plastic.[144]

Competitors

Pepsi, the flagship product of PepsiCo, the Coca-Cola Company's main rival in the soft drink industry, is usually second to Coke in sales, and outsells Coca-Cola in some markets. RC Cola, now owned by the Dr Pepper Snapple Group, the third-largest soft drink manufacturer, is also widely available.[145]

Around the world, many local brands compete with Coke. In South and Central America Kola Real, also known as Big Cola, is a growing competitor to Coca-Cola.[146] On the French island of Corsica, Corsica Cola, made by brewers of the local Pietra beer, is a growing competitor to Coca-Cola. In the French region of Brittany, Breizh Cola is available. In Peru, Inca Kola outsells Coca-Cola, which led the Coca-Cola Company to purchase the brand in 1999. In Sweden, Julmust outsells Coca-Cola during the Christmas season.[147] In Scotland, the locally produced Irn-Bru was more popular than Coca-Cola until 2005, when Coca-Cola and Diet Coke began to outpace its sales.[148] In the former East Germany, Vita Cola, invented during communist rule, is gaining popularity.

While Coca-Cola does not have the majority of the market share in India, The Coca-Cola Company's other brands like Thums Up and Sprite perform well. The Coca-Cola Company purchased Thums Up in 1993 when they re-entered the Indian market.[149] As of 2023[update], Coca-Cola held a 9% market-share in India while Thums Up and Sprite had a 16% and 20% market share respectively.[150]

Tropicola, a domestic drink, is served in Cuba instead of Coca-Cola, due to a United States embargo. French brand Mecca-Cola[151] and British brand Qibla Cola[152] are competitors to Coca-Cola in the Middle East.

In Turkey, Cola Turka, in Iran and the Middle East, Zamzam and Parsi Cola, in some parts of China, Future Cola, in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, Kofola, in Slovenia, Cockta, and the inexpensive Mercator Cola, sold only in the country's biggest supermarket chain, Mercator, are some of the brand's competitors.[153]

In 2021, Coca-Cola petitioned to cancel registrations for the marks Thums Up and Limca issued to Meenaxi Enterprise, Inc. based on misrepresentation of source. The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board concluded that "Meenaxi engaged in blatant misuse in a manner calculated to trade on the goodwill and reputation of Coca-Cola in an attempt to confuse consumers in the United States that its Thums Up and Limca marks were licensed or produced by the source of the same types of cola and lemon-lime soda sold under these marks for decades in India."[154]

Advertising

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2020) |

Coca-Cola's advertising has significantly affected American culture, and it is frequently credited with inventing the modern image of Santa Claus as an old man in a red-and-white suit. Although the company did start using the red-and-white Santa image in the 1930s, with its winter advertising campaigns illustrated by Haddon Sundblom, the motif was already common.[155][156] Coca-Cola was not even the first soft drink company to use the modern image of Santa Claus in its advertising: White Rock Beverages used Santa in advertisements for its ginger ale in 1923, after first using him to sell mineral water in 1915.[157][158] Before Santa Claus, Coca-Cola relied on images of smartly dressed young women to sell its beverages. Coca-Cola's first such advertisement appeared in 1895, featuring the young Bostonian actress Hilda Clark as its spokeswoman.

1941 saw the first use of the nickname "Coke" as an official trademark for the product, with a series of advertisements informing consumers that "Coke means Coca-Cola".[159] In 1971, a song from a Coca-Cola commercial called "I'd Like to Teach the World to Sing", produced by Billy Davis, became a hit single. During the 1950s the term cola wars emerged, describing the on-going battle between Coca-Cola and Pepsi for supremacy in the soft drink industry. Coca-Cola and Pepsi were competing with new products, global expansion, US marketing initiatives and sport sponsorships.[160]

Coke's advertising is pervasive, as one of Woodruff's stated goals was to ensure that everyone on Earth drank Coca-Cola as their preferred beverage. This is especially true in southern areas of the United States, such as Atlanta, where Coke was born.

Some Coca-Cola television commercials between 1960 through 1986 were written and produced by former Atlanta radio veteran Don Naylor (WGST 1936–1950, WAGA 1951–1959) during his career as a producer for the McCann Erickson advertising agency. Many of these early television commercials for Coca-Cola featured movie stars, sports heroes, and popular singers.

During the 1980s, Pepsi ran a series of television advertisements showing people participating in taste tests demonstrating that, according to the commercials, "fifty percent of the participants who said they preferred Coke actually chose the Pepsi."[161] Coca-Cola ran ads to combat Pepsi's ads in an incident sometimes referred to as the cola wars; one of Coke's ads compared the so-called Pepsi challenge to two chimpanzees deciding which tennis ball was furrier. Thereafter, Coca-Cola regained its leadership in the market.

Selena was a spokesperson for Coca-Cola from 1989 until the time of her death. She filmed three commercials for the company. During 1994, to commemorate her five years with the company, Coca-Cola issued special Selena coke bottles.[162]

The Coca-Cola Company purchased Columbia Pictures in 1982, and began inserting Coke-product images into many of its films.[163] After a few early successes during Coca-Cola's ownership, Columbia began to underperform, and the studio was sold to Sony in 1989.[164]

Coca-Cola has gone through a number of different advertising slogans in its long history, including "It's the real thing",[165] "The pause that refreshes",[165] "I'd like to buy the world a Coke",[166] and "Coke is it".[167]

In 1999, the Coca-Cola Company introduced the Coke Card, a loyalty program that offered deals on items like clothes, entertainment and food when the cardholder purchased a Coca-Cola Classic. The scheme was cancelled after three years, with a Coca-Cola spokesperson declining to state why.[168]

The company then introduced another loyalty campaign in 2006, My Coke Rewards. This allows consumers to earn points by entering codes from specially marked packages of Coca-Cola products into a website. These points can be redeemed for various prizes or sweepstakes entries.[169]

In Australia in 2011, Coca-Cola began the "share a Coke" campaign, where the Coca-Cola logo was replaced on the bottles and replaced with first names. Coca-Cola used the 150 most popular names in Australia to print on the bottles.[170][171][172] The campaign was paired with a website page, Facebook page, and an online "share a virtual Coke". The same campaign was introduced to Coca-Cola, Diet Coke and Coke Zero bottles and cans in the UK in 2013.[173][174]

Coca-Cola has also advertised its product to be consumed as a breakfast beverage, instead of coffee or tea for the morning caffeine.[175][176]

5 cents

From 1886 to 1959, the price of Coca-Cola was fixed at five cents, in part due to an advertising campaign.

Holiday campaigns

Throughout the years, Coca-Cola has released limited-time collector bottles for Christmas.

The "Holidays are coming!" advertisement features a train of red delivery trucks, emblazoned with the Coca-Cola name and decorated with Christmas lights, driving through a snowy landscape and causing everything that they pass to light up and people to watch as they pass through.[177]

The advertisement fell into disuse in 2001, as the Coca-Cola Company restructured its advertising campaigns so that advertising around the world was produced locally in each country, rather than centrally in the company's headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia.[178] In 2007, the company brought back the campaign after, according to the company, many consumers telephoned its information center saying that they considered it to mark the beginning of Christmas.[177] The advertisement was created by US advertising agency Doner, and has been part of the company's global advertising campaign for many years.[179]

Keith Law, a producer and writer of commercials for Belfast CityBeat, was not convinced by Coca-Cola's reintroduction of the advertisement in 2007, saying that "I do not think there's anything Christmassy about HGVs and the commercial is too generic."[180]

In 2001, singer Melanie Thornton recorded the campaign's advertising jingle as a single, "Wonderful Dream (Holidays Are Coming)", which entered the pop-music charts in Germany at no. 9.[181][182] In 2005, Coca-Cola expanded the advertising campaign to radio, employing several variations of the jingle.[183]

In 2011, Coca-Cola launched a campaign for the Indian holiday Diwali. The campaign included commercials, a song, and an integration with Shah Rukh Khan's film Ra.One.[184][185][186]

In November 2024, Coca-Cola released three short AI-generated videos as its Christmas ads, drawing backlash on social media. In a Twitter post that received more than 56 million views, Gravity Falls creator Alex Hirsch wrote: "FUN FACT: @CocaCola is 'red' because it's made from the blood of out-of-work artists! #HolidayFactz".[187][188]

Sports sponsorship

Coca-Cola was the first commercial sponsor of the Olympic Games, at the 1928 games in Amsterdam, and has been an Olympics sponsor ever since.[189] This corporate sponsorship included the 1996 Summer Olympics hosted in Atlanta, which allowed Coca-Cola to spotlight its hometown. Most recently, Coca-Cola has released localized commercials for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver; one Canadian commercial referred to Canada's hockey heritage and was modified after Canada won the gold medal game on February 28, 2010, by changing the ending line of the commercial to say "Now they know whose game they're playing".[190]

Since 1978, Coca-Cola has sponsored the FIFA World Cup, and other competitions organized by FIFA.[191] One FIFA tournament trophy, the FIFA World Youth Championship from Tunisia in 1977 to Malaysia in 1997, was called "FIFA – Coca-Cola Cup". In addition, Coca-Cola sponsors NASCAR's annual Coca-Cola 600 and Coke Zero Sugar 400 at Charlotte Motor Speedway in Concord, North Carolina and Daytona International Speedway in Daytona, Florida, respectively; since 2020, Coca-Cola has served as a premier partner of the NASCAR Cup Series, which includes holding the naming rights to the series' regular season championship trophy.[192][citation needed] Coca-Cola is also the sponsor of the iRacing Pro Series.

Coca-Cola has a long history of sports marketing relationships, which over the years have included Major League Baseball, the National Football League, the National Basketball Association, and the National Hockey League, as well as with many teams within those leagues. Coca-Cola has had a longtime relationship with the NFL's Pittsburgh Steelers, due in part to the now-famous 1979 television commercial featuring "Mean Joe" Greene, leading to the two opening the Coca-Cola Great Hall at Heinz Field in 2001 and a more recent Coca-Cola Zero commercial featuring Troy Polamalu.

Coca-Cola is the official soft drink of many collegiate football teams throughout the nation, partly due to Coca-Cola providing those schools with upgraded athletic facilities in exchange for Coca-Cola's sponsorship. This is especially prevalent at the high school level, which is more dependent on such contracts due to tighter budgets.

Coca-Cola was one of the official sponsors of the 1996 Cricket World Cup held on the Indian subcontinent. Coca-Cola is also one of the associate sponsors of Delhi Capitals in the Indian Premier League.

In England, Coca-Cola was the main sponsor of The Football League between 2004 and 2010, a name given to the three professional divisions below the Premier League in soccer. In 2005, Coca-Cola launched a competition for the 72 clubs of The Football League – it was called "Win a Player". This allowed fans to place one vote per day for their favorite club, with one entry being chosen at random earning £250,000 for the club; this was repeated in 2006. The "Win A Player" competition was very controversial, as at the end of the 2 competitions, Leeds United A.F.C. had the most votes by more than double, yet they did not win any money to spend on a new player for the club. In 2007, the competition changed to "Buy a Player". This competition allowed fans to buy a bottle of Coca-Cola or Coca-Cola Zero and submit the code on the wrapper on the Coca-Cola website. This code could then earn anything from 50p to £100,000 for a club of their choice. This competition was favored over the old "Win a Player" competition, as it allowed all clubs to win some money. Between 1992 and 1998, Coca-Cola was the title sponsor of the Football League Cup (Coca-Cola Cup), the secondary cup tournament of England. Starting in 2019–20 season, Coca-Cola has agreed its biggest UK sponsorship deal by becoming Premier League soccer's seventh and final commercial partner[193] for the UK and Ireland, China, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Egyptian and the West African markets.

Between 1994 and 1997, Coca-Cola was also the title sponsor of the Scottish League Cup, renaming it to the Coca-Cola Cup like its English counterpart. From 1998 to 2001, the company was the title sponsor of the Irish League Cup in Northern Ireland, where it was named the Coca-Cola League Cup.

Coca-Cola is the presenting sponsor of the Tour Championship, the final event of the PGA Tour held each year at East Lake Golf Club in Atlanta, Georgia.[194]

Introduced March 1, 2010, in Canada, to celebrate the 2010 Winter Olympics, Coca-Cola sold gold colored cans in packs of 12 355 mL (12 imp fl oz; 12 US fl oz) each, in select stores.[195]

Coca-Cola which has been a partner with UEFA since 1988.[196]

In mass media

Coca-Cola has been prominently featured in many films and television programs. It was a major plot element in films such as One, Two, Three, The Coca-Cola Kid, and The Gods Must Be Crazy, among many others. In music, such as in the Beatles' song, "Come Together", the lyrics say, "He shoot Coca-Cola". The Beach Boys also referenced Coca-Cola in their 1964 song "All Summer Long", singing "Member when you spilled Coke all over your blouse?"[197]

The best selling solo artist of all time[198] Elvis Presley, promoted Coca-Cola during his last tour of 1977.[199] The Coca-Cola Company used Presley's image to promote the product.[200] For example, the company used a song performed by Presley, "A Little Less Conversation", in a Japanese Coca-Cola commercial.[201]

Other artists that promoted Coca-Cola include David Bowie,[202] George Michael,[203] Elton John,[204] and Whitney Houston,[205] who appeared in the Diet Coke commercial, among many others.

Not all musical references to Coca-Cola went well. A line in "Lola" by the Kinks was originally recorded as "You drink champagne and it tastes just like Coca-Cola." When the British Broadcasting Corporation refused to play the song because of the commercial reference, lead singer Ray Davies re-recorded the lyric as "it tastes just like cherry cola" to get airplay for the song.[206][207]

Political cartoonist Michel Kichka satirized a famous Coca-Cola billboard in his 1982 poster "And I Love New York." On the billboard, the Coca-Cola wave is accompanied by the words "Enjoy Coke." In Kichka's poster, the lettering and script above the Coca-Cola wave instead read "Enjoy Cocaine."[208]

Use as political and corporate symbol

Coca-Cola has a high degree of identification with the United States, being considered by some an "American Brand" or as an item representing America, criticized as Cocacolonization. After World War II, this gave rise to the brief production of White Coke at the request of and for Soviet Marshal Georgy Zhukov, who did not want to be seen drinking a symbol of American imperialism. The bottles were given by the President Eisenhower during a conference, and Marshal Zhukov enjoyed the drink. The bottles were disguised as vodka bottles, with the cap having a red star design, to avoid suspicion of Soviet officials.[209]

Coca-Cola was introduced to China in 1927, and was very popular until 1949. After the Chinese Civil War ended in 1949, the beverage was no longer imported into China, as it was perceived to be a symbol of decadent Western culture and capitalist lifestyle. Importation and sales of the beverage resumed in 1979, after diplomatic relations between the United States and China were restored.[210] The agreement to allow Coca-Cola into the Chinese market was reached during Deng Xiaoping's visit to the United States.[211]: 137

There are some consumer boycotts of Coca-Cola in Arab countries due to Coke's early investment in Israel during the Arab League boycott of Israel (its competitor Pepsi stayed out of Israel).[212] Mecca-Cola and Pepsi are popular alternatives in the Middle East.[213]

A Coca-Cola fountain dispenser (officially a Fluids Generic Bioprocessing Apparatus or FGBA) was developed for use on the Space Shuttle as a test bed to determine if carbonated beverages can be produced from separately stored carbon dioxide, water, and flavored syrups and determine if the resulting fluids can be made available for consumption without bubble nucleation and resulting foam formation. FGBA-1 flew on STS-63 in 1995 and dispensed pre-mixed beverages, followed by FGBA-2 on STS-77 the next year. The latter mixed CO₂, water, and syrup to make beverages. It supplied 1.65 liters each of Coca-Cola and Diet Coke.[214][215]

The drink is also often a metonym for the Coca-Cola Company.

Medicinal application

Coca-Cola is sometimes used for the treatment of gastric phytobezoars. In about 50% of cases studied, Coca-Cola alone was found to be effective in gastric phytobezoar dissolution. This treatment can however result in the potential of developing small bowel obstruction in a minority of cases, necessitating surgical intervention.[216]

Criticism

Criticism of Coca-Cola has arisen from various groups around the world, concerning a variety of issues, including health effects, environmental issues, and business practices. The drink's coca flavoring, and the nickname "Coke", remain a common theme of criticism due to the relationship with the illegal drug cocaine. In 1911, the US government seized 40 barrels and 20 kegs of Coca-Cola syrup in Chattanooga, Tennessee, alleging the caffeine in its drink was "injurious to health", leading to amended food safety legislation.[217]

Beginning in the 1940s, PepsiCo started marketing their drinks to African Americans, a niche market that was largely ignored by white-owned manufacturers in the US, and was able to use its anti-racism stance as a selling point, attacking Coke's reluctance to hire blacks and support by the chairman of the Coca-Cola Company for segregationist Governor of Georgia Herman Talmadge.[218] As a result of this campaign, PepsiCo's market share as compared to Coca-Cola's shot up dramatically in the 1950s with African American soft-drink consumers three times more likely to purchase Pepsi over Coke.[219]

The Coca-Cola Company, its subsidiaries and products have been subject to sustained criticism by consumer groups, environmentalists, and watchdogs, particularly since the early 2000s.[220] In 2019, BreakFreeFromPlastic named Coca-Cola the single biggest plastic polluter in the world. After 72,541 volunteers collected 476,423 pieces of plastic waste from around where they lived, a total of 11,732 pieces were found to be labeled with a Coca-Cola brand (including the Dasani, Sprite, and Fanta brands) in 37 countries across four continents.[221] At the 2020 World Economic Forum in Davos, Coca-Cola's head of sustainability, Bea Perez, said customers like them because they reseal and are lightweight, and "business won't be in business if we don't accommodate consumers."[222] In February 2022, Coca-Cola announced that it will aim to make 25 percent of its packaging reusable by 2030.[223]

Coca-Cola Classic is rich in sugars, especially sucrose, which causes dental caries when consumed regularly. Besides this, the high caloric value of the sugars themselves can contribute to obesity. Both are major health issues in the developed world.[224]

In February 2021, Coca-Cola received criticism after a video of a training session, which told employees to "try to be less white", was leaked by an employee. The session also said in order to be "less white" employees had to be less "arrogant" and "defensive".[225][226]

The company, along with Pepsico and other American conglomerates, has faced criticism and an ongoing boycott by the pro-Palestine movement, especially in the aftermath of the 2023-24 Israel-Gaza War.[227][228] Critics pointed to the company's ties with Israel, including its donations to far-right Zionist organization Im Tirtzu, to justify the boycott.[229] In June 2024, Coca-Cola's Bangladesh distributor ran an ad in Bangladesh—where it faced a heavy boycott—attempting to distance the company from Israel.[230]

Colombian death-squad allegations

In July 2001, the Coca-Cola Company was sued over its alleged use of far-right death squads (the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia) to kidnap, torture, and kill Colombian bottler workers that were linked with trade union activity. Coca-Cola was sued in a US federal court in Miami by the Colombian food and drink union Sinaltrainal. The suit alleged that Coca-Cola was indirectly responsible for having "contracted with or otherwise directed paramilitary security forces that utilized extreme violence and murdered, tortured, unlawfully detained or otherwise silenced trade union leaders". This sparked campaigns to boycott Coca-Cola in the UK, US, Germany, Italy, and Australia.[231][232] Javier Correa, the president of Sinaltrainal, said the campaign aimed to put pressure on Coca-Cola "to mitigate the pain and suffering" that union members had suffered.[232]

Speaking from the Coca-Cola Company's headquarters in Atlanta, company spokesperson Rafael Fernandez Quiros said "Coca-Cola denies any connection to any human-rights violation of this type" and added "We do not own or operate the plants".[233]

Other uses

Coca-Cola can be used to remove grease and oil stains from concrete,[234] metal, and clothes.[235] It is also used to delay concrete from setting.[236]

See also

References

- ^ Elmore, 2013, p. 717

- ^ "Coca-Cola". Fortune. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

- ^ "Best Global Brands - The 100 Most Valuable Global Brands". Interbrand. Retrieved June 9, 2024.

- ^ a b Eschner, Kat (March 29, 2017). "Coca-Cola's Creator Said the Drink Would Make You Smarter". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on August 14, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

So Pemberton concocted a recipe using coca leaves, kola nuts and sugar syrup. "His new product debuted in 1886: 'Coca-Cola: The temperance drink,'" writes Hamblin.

- ^ Greenwood, Veronique (September 23, 2016). "The little-known nut that gave Coca-Cola its name". BBC. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ^ Ivana Kottasova (February 18, 2014). "Does formula mystery help keep Coke afloat?". CNN. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ Geuss, Megan (October 2010). "First Coupon Ever". Wired. Vol. 18, no. 11. p. 104.

- ^ Richard Gardiner, "The Civil War Origin of Coca-Cola in Columbus, Georgia," Muscogiana: Journal of the Muscogee Genealogical Society (Spring 2012), Vol. 23: 21–24.

- ^ "Coca-Cola Inventor was Local Pharmacist". Columbus Ledger. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

- ^ "Columbus helped make Coke's success". Columbus Ledger-Enquirer. March 27, 2011. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved August 12, 2012.

- ^ Patent Office, United States (1886). Annual Report of the Patent Office, 1885. Archived from the original on April 23, 2023. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- ^ "pemberton_1.jpg". Archived from the original on September 8, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2014 – via columbusstate.edu.

- ^ Pendergrast, Mark (2000). For God, Country and Coca-Cola. Basic Books. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-465-05468-8.

- ^ Blanding, Michael (2010). The Coke machine : the dirty truth behind the world's favorite soft drink. New York: Avery. pp. 14. ISBN 9781583334065. OCLC 535490831.

- ^ "Spanish town claims origins of Coca-Cola". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 2, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Montón, Lorena (September 18, 2024). "El origen español de la Coca-Cola es real". RTVE (in Spanish). Retrieved September 21, 2024.

- ^ Hayes, Jack. "Coca-Cola Television Advertisements: Dr. John S. Pemberton". Nation's Restaurant News. Archived from the original on January 6, 2007. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

- ^ The Coca-Cola Company. "The Chronicle Of Coca-Cola". Archived from the original on September 17, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ Harford, Tim (May 11, 2007). "The Mystery of the 5-Cent Coca-Cola: Why it's so hard for companies to raise prices". Slate. Archived from the original on May 14, 2007. Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ^ "Themes for Coca-Cola Advertising (1886–1999)". Archived from the original on March 3, 2007. Retrieved February 11, 2007.

- ^ Pendergrast, Mark (2000). For God, Country and Coca-Cola. Basic Books. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-465-05468-8.

- ^ Pendergrast, Mark (2000). For God, Country and Coca-Cola. Basic Books. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-465-05468-8.

- ^ a b Pendergrast, Mark (2000). For God, Country and Coca-Cola. Basic Books. pp. 45–47. ISBN 978-0-465-05468-8.

- ^ Pendergrast, Mark (2000). For God, Country and Coca-Cola. Basic Books. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-465-05468-8.

- ^ a b Candler, Charles Howard (1950). Asa Griggs Candler. Georgia: Emory University. p. 81.

- ^ a b Pendergrast, Mark (2000). For God, Country and Coca-Cola. Basic Books. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0-465-05468-8.

- ^ Pendergrast, Mark (2000). For God, Country and Coca-Cola. Basic Books. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-465-05468-8.

- ^ Pendergrast, Mark (2000). For God, Country and Coca-Cola. Basic Books. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-465-05468-8.

- ^ Pendergrast, Mark (2000). For God, Country and Coca-Cola. Basic Books. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-465-05468-8.

- ^ "This Day in Georgia History – Coca-Cola Sale Completed – GeorgiaInfo". usg.edu. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Robert W. Woodruff (1889–1985)". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Wood, Benjamin; Ruskin, Gary; Sacks, Gary (January 2020). "How Coca-Cola Shaped the International Congress on Physical Activity and Public Health: An Analysis of Email Exchanges between 2012 and 2014". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 17 (23): 8996. doi:10.3390/ijerph17238996. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 7730322. PMID 33287097.

- ^ "World of Coke exhibit shares story of forgotten 'Sprite Boy'". Archived from the original on April 2, 2023. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ^ a b "Coca-Cola Enterprises : Our Story". Coca-Cola Enterprises. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015.

- ^ The Coca-Cola Company. "History of Bottling". Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ^ "Mar 12, 1894 CE: First Bottles of Coca-Cola". National Geographic Society. December 17, 2013. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ "Coca-Cola History". worldofcoca-cola.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Chattanooga Coca-Cola History" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- ^ a b "History Of Bottling". Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ First painted wall sign to advertise Coca-Cola : Cartersville, GA Archived March 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine – Waymarking

- ^ Staff, The Doctors Book of Home Remedies. Nausea: 10 Stomach-Soothing Solutions Archived May 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Example: Flent's Cola Syrup Label says "For Simple Nausea associated with an upset stomach.* *These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease."

- ^ "Atlanta Jews and Coca-Cola". Archived from the original on August 21, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Beyond Seltzer Water: The Kashering of Coca-Cola". American Jewish Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 17, 2010. Retrieved February 26, 2007.

- ^ Melany Love (August 31, 2023). "If You See a Yellow Cap on Coca-Cola, This Is What It Means". Reader's Digest.

- ^ "Fleeman's Pharmacy (now the Belly General Store)". Archived from the original on December 17, 2003.

- ^ "Jack Fleeman – 86 – Owner". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Georgia. August 17, 2009. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012.

- ^ "Coke Can History". Archived from the original on May 30, 2012.

- ^ "A History of Sugar Prices". Archived from the original on September 1, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Ennis, Thomas W. (January 5, 1972). "Sugar Futures up on Soviet Buying". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 1, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ "New Coke – Top 10 Bad Beverage Ideas". Time. April 23, 2010. Archived from the original on November 21, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Rory Carroll in Baghdad (July 5, 2005). "Cola wars as Coke moves on Baghdad". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

- ^ "Compare Coca-Cola and Pepsi's marketing strategies". www.ukessays.com. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ a b McKay, Betsy (January 30, 2009). "Coke to Omit 'Classic'". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Klinemann, Jeffrey (January 31, 2013). "PepsiCo's in the Club... Store, that is, Capturing Costco Food Service Account". BevNET. Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ Fredrix, Emily; Skidmore, Sarah (November 17, 2009). "Costco nixes Coke products over pricing dispute". Google News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 20, 2009.

- ^ Esterl, Mike (September 19, 2011). "Coke Tailors Its Soda Sizes". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ "Coca-Cola returns to Burma after a 60-year absence". BBC News. June 14, 2012. Archived from the original on October 22, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Jordan, Tony (June 14, 2012). "Coca-Cola Announces Will Return to Myanmar After 60 Years". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Calderon, Justin (June 4, 2013). "Coca-Cola starts bottling in Myanmar". Inside Investor. Archived from the original on September 18, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- ^ "Coca-Cola to invest Rs 28,000 cr in India". June 26, 2012. Archived from the original on September 17, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Coca-Cola turns to 100% recycled plastic bottles in U.S." Reuters. February 9, 2021. Archived from the original on February 7, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ "Coca-Cola company trials first paper bottle". BBC News. February 12, 2021. Archived from the original on July 10, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "Home of Coca-Cola UK : Diet Coke : Coke Zero – Coca-Cola GB". Letsgettogether.co.uk. April 13, 2010. Archived from the original on May 15, 2010. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

- ^ "Foods List". usda.gov. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Gene A. Spiller (1998). "Appendix 1: Caffein Content of Some Cola Beverages". Caffeine. CRC. ISBN 978-0-8493-2647-9. Archived from the original on April 23, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ "The Daily Plate". The Daily Plate. Retrieved March 13, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Coca-Cola formula, after 86 years in vault, gets new home". The Christian Science Monitor. December 8, 2011. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Urban Legends Reference Pages: Cokelore". Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved February 10, 2007.

- ^ "Urban Legends Reference Pages: Cokelore (Have a Cloak and a Smile)". November 18, 1999. Archived from the original on December 1, 2005. Retrieved February 22, 2007.

- ^ Katie Rogers, "'This American Life' bursts Coca-Cola's bubble: What's in that original recipe, anyway?", The Washington Post BlogPost, February 15, 2011. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ Brett Michael Dykes, "Did NPR's 'This American Life' discover Coke's secret formula?", Archived February 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine The Lookout, Yahoo! News, February 15, 2011.

- ^ David W. Freeman, "'This American Life' Reveals Coca-Cola's Secret Recipe (Full Ingredient List)", Archived February 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine CBS News Healthwatch blogs, February 15, 2011.

- ^ The Recipe Archived February 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, This American Life.

- ^ "Coca-cola". Pponline.co.uk. Archived from the original on November 15, 2009. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

- ^ "The History of Coca-Cola". Archived from the original on March 15, 2009. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ^ "Cocaine Facts - How to Tell Use of Cocaine - Questions, Myths, Truth". thegooddrugsguide.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Liebowitz, Michael, R. (1983). The Chemistry of Love. Boston: Little, Brown, & Co.

- ^ "Is it true Coca-Cola once contained cocaine?". June 14, 1985. Archived from the original on February 21, 2007. Retrieved February 27, 2007.

- ^ "Coca-Cola's Scandalous Past". March 2012. Archived from the original on May 24, 2022. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ May, Clifford D. (July 1, 1988). "How Coca-Cola Obtains Its Coca". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 20, 2019. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

A Stepan laboratory in Maywood, N.J., is the nation's only legal commercial importer of coca leaves, which it obtains mainly from Peru and, to a lesser extent, Bolivia. Besides producing the coca flavoring agent sold to The Coca-Cola Company, Stepan extracts cocaine from the coca leaves, which it sells to Mallinckrodt Inc., a St. Louis pharmaceutical manufacturer that is the only company in the United States licensed to purify the product for medicinal use

- ^ Benson, Drew. "Coca kick in drinks spurs export fears". Archived from the original on May 30, 2012.

- ^ "Dope Wagons". ncpedia.org. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Text of United States v. Forty Barrels & Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola, 241 U.S. 265 (1916) is available from: CourtListener Findlaw Justia Library of Congress

- ^ "Offices & Bottling Plants". Archived from the original on February 16, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ "What Is the Difference Between Coca-Cola Enterprises and the Coca-Cola Company". Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ Stafford, Leon (September 9, 2012). "Coca-Cola to spend $30 billion to grow globally". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- ^ Weissert, Will (May 15, 2007). "Cuba stocks US brands despite embargo". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ Ryall, Julian (August 31, 2012). "Coca-Cola denies 'cracking' North Korea". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on September 6, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ Wiener-Bronner, Danielle (March 9, 2022). "McDonald's, Starbucks and Coca-Cola leave Russia". CNN Business. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ a b Liebesny, Herbert J. (1975). The law of the Near and Middle East readings, cases, and materials. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 9780585090207.

- ^ a b "Bite the Wax Tadpole". Snopes. April 5, 1999. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Transliteration of 'Coca-Cola' Trademark to Chinese Characters". ATIS - Australian Translating and Interpreting Service. Archived from the original on May 22, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ "Coca-Cola in Chinese is Ke-kou-ke-la". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ "可口可乐"—— 中文翻译的经典之作. Archived from the original on September 18, 2018. Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- ^ 鄭明仁:「可口可樂」中文名稱翻譯之謎. www.thinkhk.com. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Armand, Cécile. ""Placing the history of advertising": A spatial history of advertising in modern Shanghai (1905-1949)". purl.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on July 14, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Huddleston, Tom Jr. (July 5, 2019). "Netflix's 'Stranger Things' revives New Coke. Here's how the failed soda cost Coca-Cola millions in 1985". CNBC. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "Coke With Coffee Discontinued in U.S." Beverage Digest. November 9, 2022. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Peach Coca-Cola coming to Japan in a world-first for the company". January 10, 2018.

- ^ "Coca-Cola Japan releases new Peach Coke for 2019". December 21, 2018.

- ^ a b "Coca-Cola Local Flavors - Varieties & Details | Coca-Cola US".

- ^ Meyer, Zlati (February 8, 2019). "Coca-Cola debuts Orange Vanilla, its first new flavor in more than a decade". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Coca-Cola Energy: First energy drink released under Coke brand". March 28, 2019.

- ^ "Coca-Cola Great Britain announces the launch of Coca-Cola Energy". Archived from the original on May 26, 2019.

- ^ Wienner-Bronner, Danielle (October 1, 2019). "Coca-Cola Energy is coming to the United States". CNN.com. Archived from the original on December 24, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Coca-Cola discontinues energy drink in N.America". Reuters. May 14, 2021. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "Discover the Coca-Cola Signature Mixers range". February 4, 2021.

- ^ "Coca-Cola discontinues Signature Mixers range".

- ^ "新登場!秋の味覚・りんごが贅沢に香る「コカ・コーラ」世界初の「コカ・コーラ アップル」9月16日(月・祝)から期間限定発売".

- ^ Moye, Jay (September 30, 2019). "Priming the Innovation Pump: Coca-Cola Debuts Diverse Lineup of New Drinks at NACS". The Coca-Cola Company. Archived from the original on October 3, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Coca-Cola Japan releases their first-ever strawberry coke". January 8, 2020.

- ^ "Coke to launch Coca-Cola Energy and new cherry flavour in the US". October 3, 2019.

- ^ "Coca-Cola Energy debuts brand new cherry variant plus extra Coca-Cola taste for all variants".

- ^ "Coca-Cola Launches Global Innovation Platform Coca-Cola Creations". Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Coca-Cola Creations - Essential Marketing". August 11, 2022. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Coca-Cola's new Intergalactic and Byte drinks taste of the future". April 27, 2022. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Game On: Coca-Cola and Riot Games Team Up for 'Ultimate' Flavor and Experiences Celebrating Every Player's Journey". www.coca-colacompany.com. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Jack Daniel's® and Coca-Cola® RTD Launches in Great Britain".

- ^ "Ready to Drink Jack and Coke Launches".

- ^ "Discover Coca-Cola Spiced: A New Raspberry & Spice Sensation". Coca-Cola. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Coca-Cola is pulling its newest 'permanent' flavor from store shelves". ABC7 Los Angeles. September 24, 2024. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ "Coca-Cola Company – Red Spencerian Script". Archived from the original on March 15, 2009. Retrieved January 11, 2007.