Coal in China

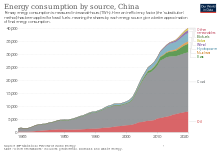

China is the largest producer and consumer of coal and coal power in the world. The share of coal in the Chinese energy mix declined to 55% in 2021 according to the US Energy Information Agency.[1]

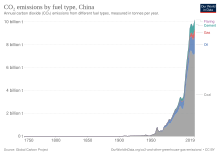

The Chinese central government has clamped down on the pace of new construction of coal plants and shifted to renewable, nuclear and natural gas sources.[2] At the same time, coal consumption reached new heights in China with carbon dioxide emissions from coal-fired electricity production estimated to top 4.5 billion tonnes in 2022. Reuters noted in 2022, "China is set to delight and depress climate trackers in equal measure in 2022 by setting new global records in both clean power utilisation and coal-fired electricity emissions."

Solar and wind-generated electricity surged by over 30% and 25% respectively during the period from January to October 2022 compared to the same period in 2021.[3] Despite central government attempts to clamp down on construction and shifting demand in the market to renewable, nuclear and natural gas sources,[2] 43 coal power units were announced in the first half of 2021 according to the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air in August 2021.[4]

In September 2021, China pledged to end financing of coal power plants abroad.[5] A study by Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air in April 2022 stated at least 15 overseas coal power plants had been cancelled since the announcement, while 18 projects which had secured financing and necessary permits could enter into construction.[6]

During the 2021 energy crisis in China, this dependency on coal units, depletion of reserves, increasing import prices, and slowdowns of shipment and production lead to widespread shutdowns of industrial energy use.[7][8]

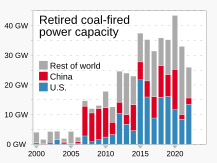

In 2022, global coal phase-out efforts advanced, excluding China, which increased coal capacity, offsetting global reductions.[9]

History

[edit]

Coal mines in pre-industrial China

[edit]Ancient people in current China started using coal around 6,000 years ago.[10] Historians suspects that the Chinese were involved in the surface mining of coal around 3490 BC, pioneering the pre-modern world.[11] Fushan mine uses[clarification needed] to be pointed out as the earliest coal mine in the ancient world and started around 1000 BC. In pre-modern China, coal was constrained both by the limitations of traditional technology and the weakness of demand.[12]

In the 3rd century BC, Chinese people began burning coal for heat.[13] The spread of coal use was gradual until the late 11th century when a timber shortage in north China produced a fast-paced expansion in coal mining and consumption.[12] In 1000 AD, Chinese mines were ahead of most mining advancements[clarification needed] in the world.[13]

Coal mines in China faced similar problems to European ones. Both Chinese and European miners preferred to use drift mines sunk horizontally into the hillside for drainage of water. In the 18th century, British observers realized that such mines in Guangdong were opening out directly on to a river. Slope mines were the second most common type, as mines in Leiyang, Hunan.[12]

In the 19th century, shaft mines were predominant, especially in north China. European observers interpreted that as a consequence of the lack of wood in the zone to hold up the roof in slope mines. Flooding was a constant problem, and several mines were abandoned for that reason.[12]

Coal mines in China were as deep as those in Europe. In areas such as Shanxi with natural drainage, mines were as deep as 120 m. From Henan and Manchuria, mines had depths of 90 m or more.[12]

Early coal consumption in China

[edit]Coal consumption in traditional China was substantial but low on a per capita basis. Main coal demand came from industry. The earliest references to coal are in the context of smelting methods. The technology was spread from the central plain to outlying areas in China.[12]

In the 11th century, the iron produced in north China was smelted in coke-burning blast-furnaces. Deforestation in that zone forced to turn to the use of coke, mushrooming ironworking centers along the Henan-Hebei border. Accounts of that period estimate that at least 140 000 tons of coal a year were used by the iron industry in that zone. Chinese scientist Song Yingxing suggested that around 70% of iron was smelted with coal. Meanwhile, 30% used charcoal. Shanxi was the center of the iron industry in late traditional times.[timeframe?] German scientist Ferdinand von Richthofen accounted for the use of coal in several areas of the province.[12]

Early descriptions of coal for household purposes go back until the 6th century when a writer pointed out that food tastes different according to whether it was cooked over coal, charcoal, bamboo, or grass. From the 11th century, coal was the main option in the household in the capital at Kaifeng. At the beginning of the 12th century, twenty new coal markets were established and coal replaced charcoal in the zone. Increasing demand led to the development of mining in areas of Henan and Shandong. Marco Polo claimed that coal was "burnt through the province of Cathay" and pointed out that was used in bathhouses.[12]

Production

[edit]

Coal is the most abundant mineral resource in China by a large margin.[14]: 21

Coalfields

[edit]China produces most of the thermal coal (both black and brown coal) it burns, but imports coking coal to make high quality steel.[15] Inner Mongolia, Shanxi and Shaanxi are the main coal-producing provinces,[16] and most coal is found in the north and northwest of the country.[17] This poses a large logistical problem for supplying electricity to the more heavily populated coastal areas in the southeast.[18][19]

Coal production

[edit]China is the largest coal producer in the world,[20] with 3.84 billion tonnes in 2020 and China National Coal Association forecasting an increase in 2021.[21] The coal production 1829 Mtoe in 2018 is more than the total aggregate of next nine top coal producers and 46.7% of the total global production.[22]

| Production | Net import | Net available | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2,226 | -47 | 2,179 |

| 2008 | 2,761 | nd | 2,761 |

| 2009 | 2,971 | 114 | 3,085 |

| 2010 | 3,162 | 157 | 3,319 |

| 2011 | 3,576 | 177 | 3,753 |

| 2012 | 3,549 | 278 | 3,827 |

| 2013 | 3,561 | 320 | 3,881 |

| 2014 | 3,640 | 292 | 3,932 |

| 2015 | 3,563 | 204 | 3,767 |

| 2016 | 3,268 | 282 | 3,550 |

| 2017 | 3,397 | 284 | 3,681 |

| 2018[b] | 3,550 | 295 | 3,845 |

In 2011, seven Chinese coal mining companies produced 100 million tonnes of coal or more. These companies were Shenhua Group, China Coal Group, Shaanxi Coal and Chemical Industry, Shanxi Coking Coal Group, Datong Coal Mine Group, Jizhong Energy, and Shandong Energy.[25] The largest metallurgical coal producer was Shanxi Coking Coal Group.[26]

In 2015, official statistics revealed that previous statistics had been systematically underestimated by 17%, corresponding to the entire CO2 emissions of Germany.[27]

China's largest open-pit coal mine is located in Haerwusu in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. It started production in 2008, and is operated by Shenhua Group. Its estimated coal output was forecast at 7 million tonnes in the fourth quarter of 2008. With a designed annual capacity of 20 million tonnes of crude coal, it will operate for approximately 79 years. Its coal reserves total about 1.73 billion tonnes. It is rich in low-sulfur steam coal.[28] Mines in Inner Mongolia are rapidly expanding production, with 637 million tons produced in 2009. Transport of coal from this region to seaports on China's coast has overloaded highways such as China National Highway 110 resulting in chronic traffic jams and delays.[29]

In 2021, the government ordered all coal mines to operate at full capacity at all times, including holidays; approved new mines, and reduced restrictions on coal mining.[30]

Imports

[edit]China is the world's largest importer of coal: with big imports from Russia and Indonesia in the 2020s.[31][32][33] After boycotting Australian coal in 2020, coking coal imports from Mongolia[34] and the US grew.[31] Also Russia sought to expand its coal exports to China due to declining demand in Europe because of the energy transition and the political tensions between Russia and Western countries over the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[33]

In 2023 China imported 23.47 million metric tons of coal from Australia, an increase from 2.86 million after a two-year ban was ended. The levels of coal imports from Australia did not yet reach the pre-ban levels of 77.51 million metric tons.[35] That year, Shanxi's major coal producers planned to boost production to address a significant output drop that resulted in a rare 4.1% national decline—the first since 2020. This downturn led to increased reliance on coal imports, which hit record levels. Expectations are for further increases in 2024, especially for high-quality coking and thermal coal. The China Coal Transportation and Distribution Association predicts continued import growth, driven by rising demand from the steel industry, revitalization efforts in the real estate sector, and favorable import conditions from Mongolia and Russia due to recent export duty waivers.[36]

Use

[edit]57% of energy consumption was from coal in 2020, and 49% for coal-fired power.[37] The coal consumption was 1907 Mtoe in 2018 which is 50.2% of the global consumption.[22] The National Development and Reform Commission, which determines the energy policy of China, aims to keep China's coal consumption below 3.8 billion tonnes per annum.[citation needed]

The consumption of coal is largely in power production, aside from this, there is a lot of industry and manufacturing use along with a comparatively small amount of domestic use in poorer households for heating and cooking.[32]

| Use | Anthracite | Coking Coal | Other Bituminous |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residential | 0 | 0 | 71.7 |

| Industry | 24.6 | 16.3 | 342.1 |

| Electricity Plants | 0 | 0.2 | 1305.2 |

| Heat Plants | 0 | 0.19 | 153.7 |

| Other Transformation[39] | 0 | 359.2 | 84.0 |

Electricity generation

[edit]

Coal power in China is electricity generated from coal in China and is distributed by the State Power Grid Corporation. It is a big source of greenhouse gas emissions by China.

China's installed coal-based power generation capacity was 1080 GW in 2021,[40] about half the total installed capacity of power stations in China.[41] Coal-fired power stations generated 57% of electricity in 2020.[42] Over half the world's coal-fired power is generated in China.[43] 5 GW of new coal power was approved in the first half of 2021.[41] Quotas force utility companies to buy coal power over cheaper renewable power.[44] China is the largest producer and consumer of coal in the world and is the largest user of coal-derived electricity. Despite China (like other G20 countries) pledging in 2009 to end inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, as of 2020[update] there are direct subsidies and the main way coal power is favoured is by the rules guaranteeing its purchase – so dispatch order is not merit order.[45]

The think tank Carbon Tracker estimated in 2020 that the average coal fleet loss was about 4 USD/MWh and that about 60% of power stations were cashflow negative in 2018 and 2019.[46] In 2020 Carbon Tracker estimated that 43% of coal-fired plants were already more expensive than new renewables and that 94% would be by 2025.[47] According to 2020 analysis by Energy Foundation China, to keep warming to 1.5 degrees C all China's coal power without carbon capture must be phased out by 2045.[48] But in 2023 many new coal power stations were approved.[49] Coal power stations receive payments for their capacity.[50] A 2021 study estimated that all coal power plants could be shut down by 2040, by retiring them at the end of their financial lifetime.[51]

To curtail the continued rapid construction of coal fired power plants, strong action was taken in April 2016 by the National Energy Administration (NEA), which issued a directive curbing construction in many parts of the country.[55] This was followed up in January 2017 when the NEA canceled a further 103 coal power plants, eliminating 120 GW of future coal-fired capacity, despite the resistance of local authorities mindful of the need to create jobs.[56] The decreasing rate of construction is due to the realization that too many power plants had been built and some existing plants were being used far below capacity.[57] In 2020 over 40% of plants were estimated to be running at a net loss and new plants may become stranded assets.[45] In 2021 some plants were reported close to bankruptcy due to being forbidden to raise electricity prices in line with high coal prices.[58]

As part of China's efforts to achieve its pledges of peak coal consumption by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060, a nationwide effort to reduce overcapacity resulted in the closure of many small and dirty coal mines.[59]: 70 Major coal-producing provinces like Shaanxi, Inner Mongolia, and Shanxi instituted administrative caps on coal output.[59]: 70 These measures contributed to electricity outages in several northeastern provinces in September 2021 and a coal shortage elsewhere in China.[59]: 70 The National Development and Reform Commission responded by relaxing some environmental standards and the government allowed coal-fired power plants to defer tax payments.[59]: 71 Trade policy was adjusted to permit the importation of a small amount of coal from Australia.[59]: 72 The energy problems abated in a few weeks.[59]: 72

In 2023, The Economist wrote that ‘Building a coal plant, whether it is needed or not, is also a common way for local governments to boost economic growth.’ and that ‘They don’t like depending on each other for energy. So, for example, a province might prefer to use its own coal plant rather than a cleaner energy source located elsewhere.’[60]Industrial use

[edit]One of the principal consumers of coal is the steel industry in China, which burns metallurgical coal.[61]

Domestic use

[edit]

In Chinese cities, the domestic burning of coal is no longer permitted. In rural areas, coal can still be used by Chinese households, and is commonly burned raw in unvented stoves. This fills homes with high levels of toxic metals leading to bad indoor air quality (IAQ). In addition, food cooked over coal fires contains toxic substances. Toxic substances from coal burning include arsenic, fluorine, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and mercury. These cause health issues such as arsenic poisoning, skeletal fluorosis (over 10 million people afflicted in China), esophageal and lung cancers, and selenium poisoning.[62]

China is now aware of the impact of coal on the environment and is taking steps to change it. Currently, China is expanding the use of natural gas as an alternative to coal for heating. But if rural areas lose government subsidies, no one will continue to use natural gas. [63]

In 2007, the use of coal and biomass (collectively referred to as solid fuels) for domestic purposes was nearly ubiquitous in rural households but declining in urban homes. At that time, estimates put the number of premature deaths due to indoor air pollution at 420,000 per year, which is even higher than due to outdoor air pollution, estimated at 300,000 deaths per year. The specific mechanisms for death cited have been respiratory illnesses, lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), weakening of the immune system, and reduction in lung function. Measured pollution levels in homes using solid fuels generally exceeded China's IAQ air quality standards. Technologies exist to improve indoor air quality, notably the installation of a chimney and modernized bioenergy but need more support to make a larger difference.[64]

Carbon footprint

[edit]

2019 carbon emissions from coal in China are estimated at 7.24 billion tonnes CO2 emissions,[65] around 14% of the world total greenhouse gas emissions of around 50 billion tonnes.[66] In 2021 the carbon price was about one-tenth of the EU carbon price.[67]

It is believed that a continued increase in coal power in China may undermine international initiatives to decrease carbon emissions, such as the Paris Agreement.[68]

Efforts to reduce emissions

[edit]Air pollution in China kills 750,000 people every year, according to a study by the World Bank.[69] Issued in response to record-high levels of air pollution in 2012 and 2013, the State Council's September 2013 Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Air Pollution reiterated the need to reduce coal's share in China's energy mix to 65% by 2017.[70] As public concern grows, incidents of social unrest are becoming more frequent around the country. For example, in December 2011 the government suspended plans to expand a coal-fired power plant in the city of Haimen after 30,000 local residents staged a violent protest against it, because "the coal-fired power plant was behind a rise in the number of local cancer patients, environmental pollution and a drop in the local fishermen's catch."[71]

In addition to environmental and health costs at home, China's dependence on coal is cause for concern on a global scale. Due in large part to the emissions caused by burning coal, China is now the number one producer of carbon dioxide, responsible for a full quarter of the world's CO2 output.[72] The country has taken steps towards battling climate change by pledging to cut its carbon intensity (the amount of CO2 produced per dollar of economic output) by about 40 percent by 2020, compared to 2005 levels.[72]

China has said carbon dioxide from coal will peak by 2025.[73] On average, China's coal plants work more efficiently than those in the United States, due to their relative youth.[74]

In September 2011, the Chinese government's Ministry of Environmental Protection announced a new emission standard for thermal power plants, for NOx and mercury, and a tightening of SO2 and soot standards. New coal power plants have a set date of the beginning of 2012 and for old power plants by mid-2014. They must also abide by a new limit on mercury by beginning of 2015. It is estimated such measures could bring about a 70% reduction in NOx emissions from power plants.[75]

As part of China's efforts to achieve its pledges of peak coal consumption by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060, a nationwide effort to reduce overcapacity resulted in the closure of many small and dirty coal mines.[76]: 70 Major coal-producing regions like Shaanxi, Inner Mongolia, and Shanxi instituted administrative caps on coal output.[76]: 70 These measures contributed to electricity outages in several northeastern provinces in September 2021 and a coal shortage elsewhere in China.[76]: 70 The National Development and Reform Commission responded by relaxing some environmental standards and the government allowed coal-fired power plants to defer tax payments.[76]: 71 Trade policy was adjusted to permit the importation of a small amount of coal from Australia.[76]: 72 The energy problems abated in a few weeks.[76]: 72

The Chinese national carbon trading scheme began in 2021.

Beijing

[edit]China decided to close the last four coal-fired power and heating plants out of Beijing's municipal area, replacing them with gas-fired power plants, in an effort to improve air quality in the capital. The four plants, owned by Huaneng Power International, Datang International Power Generation Co Ltd, China Shenhua Energy and Beijing Jingneng Thermal Power Co Ltd, had a total power generating capacity of about 2.7 gigawatts (GW).[77] All of them have been closed as of March 2019.[citation needed]

Coal mine fires

[edit]It is estimated that coal mine fires in China burn about 200 million kg of coal each year. Small illegal fires are frequent in the northern region of Shanxi. Local miners may use abandoned mines for shelter and intentionally set such fires. One study estimates that this translates into 360 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions per year, which is not included in the previous emissions figures.[78]

North China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region has announced plans to extinguish fires in the region by 2012. Most of these fires were caused by bad mining practices combined with bad weather. 200 million yuan (US$29.3 million) has been budgeted to this effect.[79]

Accidents and deaths

[edit]In 2003, the death rate per million tons of coal mined in China was 130 times higher than in the United States, 250 times higher than in Australia (open cast mines) and 10 times higher than the Russian Federation (underground mines). However the safety figures in the major state owned coal enterprises were significantly better. Even so, in 2007 China produced one third of the world's coal but had four fifths of coal fatalities.[80] China's coal mining industry resorts to forced labor according to a 2014 U.S. Department of Labor report on child labor and forced labor around the world,[81] and that these workers are all the more exposed to the dangers of such activities.

Pulmonary disease

[edit]

While not directly attributable, many more deaths are resultant from dangerous emissions from coal plants. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), linked to exposure to fine particulates, SO2, and cigarette smoke among other factors, accounted for 26% of all deaths in China in 1988.[83] A report by the World Bank in cooperation with the Chinese government found that about 750,000 people die prematurely in China each year from air pollution. Later, the government asked the researchers to soften the conclusions.[84]

Many direct deaths happen in coal mining and processing. In 2007, 1,084 out of the 3,770 workers who died were from gas blasts. Small mines (comprising 90% of all mines) are known to have far higher death rates, and the government of China has banned new coal mines with a high gas danger and a capacity below 300,000 tons in an effort to reduce deaths a further 20% by 2010. The government has also vowed to close 4,000 small mines to improve industry safety.[85]

Accidents

[edit]As of 2009, the government has been cracking down on unregulated mining operations, which in 2009 accounted for nearly 80 percent of the country's 16,000 mines. The closure of about 1,000 dangerous small mines in 2008 helped to cut in half the average number of miners killed, to about six a day, in the first six months of 2009, according to the government. Major gas explosions in coal mines remain a problem, though the number of accidents and deaths have gradually declined year by year, the chief of the State Administration of Work Safety, Luo Lin, told a national conference in September 2009.[86]

In the first nine months of 2009, China's coal mines had eleven major accidents with 303 deaths, with gas explosions the leading cause, according to the central government. Most accidents are blamed on failures to follow safety rules, including a lack of required ventilation or fire control equipment.[86]

Since 1949, over 250,000 coal mining deaths have been recorded[when?].[87]

By year

[edit]

| Year | Number of accidents | Deaths | Death rate per million tons of coal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2,863 | 5,798 | 5.80 |

| 2001 | 3,082 | 5,670 | 5.11 |

| 2002 | 4,344 | 6,995 | 4.93 |

| 2003 | 4,143 | 6,434 | 4.00 |

| 2004 | 3,639 | 6,027 | 3.01 |

| 2005 | 3,341 | 5,986 | 2.73 |

| 2006 | 2,945 | 4,746 | 1.99 |

| 2007 | 3,770 | 1.44 | |

| 2008 | 3,210 | 1.18 | |

| 2009 | 1,616 | 2,631 | 0.89 |

| 2010 | 2,433[88] | ||

| 2011 | 1,973[89] | ||

| 2012 | 1,301 | ||

| 2013 | 1,049 |

Source: State Administration of Work Safety[90]

Technology export

[edit]As of 2018[update] China is exporting technology, for example for coal mining in Turkey.[91]

Just transition to phase out coal

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2021) |

According to BloombergNEF excluding subsidies the levelized cost of electricity from new large-scale solar power has been below existing coal-fired power stations since 2021.[92] Coal production employed 2.6 million in 2020 so a just transition is important, but renewable energy creates more jobs per yuan invested.[93] Almost half of tax revenue in Shanxi province is from coal.[93] Since 2004, some local governments in Shanxi have required that coal mining companies set aside funds for investing in noncoal business like agriculture and produce processing.[94]: 54

Energy storage and demand response are important for replacing coal generation.[95] In 2020 a group of experts said that China should stop subsidizing coal.[96]

In 2022, global coal phase-out efforts continued, excluding China, where increased coal production negated worldwide advancements. The US significantly reduced coal power, contributing to half of the global decline. However, China's addition of 26.8 GW in coal power contrasted with the trend towards reducing coal dependence and enhancing renewable energy investments. China now represents 68% of the world's coal projects under development, highlighting its significant influence on global coal dynamics.[9]

International opinions

[edit]In 2020, U.N. secretary general António Guterres said that China should stop building coal-fired power stations,[97] and such building was criticized by U.S. climate envoy John Kerry in 2021 as making it difficult to limit climate change.[98]

At the 2021 United Nations General Assembly, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced China's commitment to not building new coal-fired power projects abroad, marking a significant step towards addressing climate change. This initiative, part of China's broader climate pledges, was positively received by global leaders, including U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres and U.S. climate envoy John Kerry.[99]

See also

[edit]- Other countries

References

[edit]- ^ "International - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". US Energy Information Agency.

- ^ a b "A glut of new coal-fired power stations endangers China's green ambitions". Economist. 21 May 2020.

- ^ Maguire, Gavin (23 November 2022). "China on track to hit new clean & dirty power records in 2022". Reuters.

- ^ "China's power & steel firms continue to invest in coal even as emissions surge cools down" (PDF). Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 August 2021.

- ^ "China's Xi Jinping promises to halt new coal projects abroad amid climate crisis". cnn. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "At Least 15 China-Backed Coal Plants Canceled, Another 37 GW in Limbo". Power. 24 April 2022.

- ^ "How bad is China's energy crisis?". the Guardian. 29 September 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ Seidel, Jamie (1 October 2021). "China's growing electricity crisis". news.com.au. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ a b "Global progress on phasing out coal in 2022 weighed down by China". France 24. 9 April 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ "Ancient China". Alberta Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ Cartwright, Megan. "A Brief History of Coal". WorldWide RS. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wright, Tim (1984). Coal Mining in China's Economy and Society 1895–1937. Great Britain: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521258782.

- ^ a b "Unearthing Ancient Mysteries". Alberta Culture and Tourims. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ Zhan, Jing Vivian (2022). China's Contained Resource Curse: How Minerals Shape State-Capital-Labor Relations. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-04898-9.

- ^ "Why is coal so important to China's economy?". South China Morning Post. 13 February 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ Turland, Jesse (29 September 2021). "Coal Shortages Force Blackouts Across China". The Diplomat. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ "Which countries have the highest coal reserves in the world?". www.mining-technology.com. 6 January 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ "Nuclear Power in China". Country Profiles. World Nuclear Association. 2021. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

While coal is the main energy source, most reserves are in the north or northwest and present an enormous logistical problem – nearly half the country's rail capacity is used in transporting coal.

- ^ Kemp, John (28 September 2021). "China coal production, transportation and consumption" (PDF). Energy. Thomson Reuters. p. 2. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

Coal accounts for >40% of all freight tonne-kms on the rail network

- ^ "Country analysis briefs: China". Energy Information Administration. August 2006. Archived from the original on 21 August 2011. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- ^ "China's coal consumption seen rising in 2021, imports steady". Reuters. 3 March 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ a b "BP Statistical Review 2019" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ IEA Key World Energy Statistics 2018, 2017 at the Wayback Machine (archived 2017-10-02), "2014" (PDF). Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), "2013" (PDF). Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2019.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), "2012" (PDF). Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2012.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), "2011" (PDF). Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2012.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), "2010" (PDF). Archived from the original on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 20 November 2012.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), "2009" (PDF). Archived from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2012.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), "2006" (PDF). Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 20 November 2012.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) IEA coal production p. 15, electricity p. 25 and 27 - ^ IEA Coal Information Overview 2019, 2017 at the Wayback Machine (archived 2019-08-13)

- ^ "China's 7 Coal Mining Companies Realized Production Capacity of 100 Mln Tonnes in 2011". China Mining Association. 1 February 2012. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ Le, Reggie (5 April 2012). "China's Jizhong Energy mines 31 million mt of coal, up 10% on year". Platts. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ^ Buckley, Chris (3 November 2015). "China Burns Much More Coal Than Reported, Complicating Climate Talks". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ "China's largest open-pit coal mine ready for production". Xinhua News Agency. 19 October 2008. Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ "China's Growth Leads to Problems Down the Road" Archived 2017-03-18 at the Wayback Machine "Mongolian coal production has exploded — up 37 percent to 637 million tons last year alone, with an additional 15 percent increase expected this year." article by Michael Wines in The New York Times August 27, 2010, accessed August 28, 2010

- ^ Chuin-Wei Yap (20 October 2021). "China Takes the Brakes Off Coal Production to Tackle Power Shortage". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

China has ordered all coal mines to operate at full capacity [...] It has ordered all coal mines to operate at full capacity even during holidays, issued approvals for new mines [...] China's rollback of restrictions on mining and imports of coal

- ^ a b Hui, Mary (26 August 2021). "China's boycott of Australia has redirected global flows of coal". Quartz. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ a b "China Wants To Go Carbon-Neutral — And Won't Stop Burning Coal To Get There". NPR.org. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ a b Overland, Indra; Loginova, Julia (1 August 2023). "The Russian coal industry in an uncertain world: Finally pivoting to Asia?". Energy Research & Social Science. 102: 103150. Bibcode:2023ERSS..10203150O. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2023.103150. ISSN 2214-6296.

- ^ "China eyes more coal imports from Mongolia as supply shortage bites". The Star. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "China's 2023 coal imports from Australia rise, but below pre-ban era". Ground News. 20 January 2024. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ "China's Top Coal Province to Raise Output to Boost Local Economy". www.bloomberg.com. 16 May 2024. Retrieved 25 May 2024.

- ^ Zhou, Analysts Oceana; Liang, Analyst Cindy (26 April 2021). "China set to cap coal consumption, boost domestic oil & gas output in 2021". www.spglobal.com. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "Coal and Peat in China, People's Republic of in 2007". International Energy Agency (IEA). Archived from the original on 14 September 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ Other Transformation refers to an energy transformation process not in the preceding list of electricity, industry, or heat. For the case of coal, this is likely to include losses, own use, gains, or liquefaction. Reference: [1] Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Chinese coal plant approvals slum after Xi climate pledge". South China Morning Post. 25 August 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ a b Yihe, Xu (1 September 2021). "China curbs coal-fired power expansion, giving way to renewables". Upstream. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ Cheng, Evelyn (29 April 2021). "China has 'no other choice' but to rely on coal power for now, official says". CNBC. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ "China generated half of global coal power in 2020: study". Deutsche Welle. 29 March 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ "Why China is struggling to wean itself from coal". www.hellenicshippingnews.com. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ a b "China's Carbon Neutral Opportunity" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2021.

- ^ Gray, Matt; Sundaresan, Sriya (April 2020). Political decisions, economic realities: The underlying operating cashflows of coal power during COVID-19 (Report). Carbon Tracker. p. 19.

- ^ How to Retire Early: Making accelerated coal phaseout feasible and just (Report). Carbon Tracker. June 2020.

- ^ China's New Growth Pathway: From the 14th Five-Year Plan to Carbon Neutrality (PDF) (Report). Energy Foundation China. December 2020. p. 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "China's new coal power spree continues as more provinces jump on the bandwagon". Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. 29 August 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ Lushan, Huang (23 November 2023). "China's new capacity payment risks locking in coal". China Dialogue. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ Kahrl, Fredrich; Lin, Jiang; Liu, Xu; Hu, Junfeng (24 September 2021). "Sunsetting coal power in China". iScience. 24 (9): 102939. Bibcode:2021iSci...24j2939K. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.102939. ISSN 2589-0042. PMC 8379489. PMID 34458696.

- ^ a b "Retired Coal-fired Power Capacity by Country / Global Coal Plant Tracker". Global Energy Monitor. 2023. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. — Global Energy Monitor's Summary of Tables (archive)

- ^ "Boom and Bust Coal / Tracking the Global Coal Plant Pipeline" (PDF). Global Energy Monitor. 5 April 2023. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2023.

- ^ "New Coal-fired Power Capacity by Country / Global Coal Plant Tracker". Global Energy Monitor. 2023. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. — Global Energy Monitor's Summary of Tables (archive)

- ^ Feng, Hao (7 April 2016). "China Puts an Emergency Stop on Coal Power Construction". The Diplomat.

- ^ Forsythe, Michael (18 January 2017). "China Cancels 103 Coal Plants, Mindful of Smog and Wasted Capacity". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ "Asian coal boom: climate threat or mirage?". Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit. 22 March 2016. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ "Beijing power companies close to bankruptcy petition for price hikes". South China Morning Post. 10 September 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Zhang, Angela Huyue (2024). High Wire: How China Regulates Big Tech and Governs Its Economy. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197682258.001.0001. ISBN 9780197682258.

- ^ "Will China save the planet or destroy it?". The Economist. 27 November 2023. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Staff (2 September 2021). "China puts price controls on domestic metallurgical coal: sources". www.spglobal.com. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ Robert B. Finkelman, Harvey E. Belkin, and Baoshan Zheng. Health impacts of domestic coal use in China Archived 2016-01-22 at the Wayback Machine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 March 30; 96(7): 3427–3431.

- ^ Hu, Zhanping (2021). "De-Coalizing Rural China: A Critical Examination of the Coal to Clean Heating Project from a Policy Process Perspective". Frontiers in Energy Research. 9. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2021.707492.

- ^ Environmental Health Perspectives. Household Air Pollution from Coal and Biomass Fuels in China: Measurements, Health Impacts, and Interventions Archived 2017-02-02 at the Wayback Machine. Received July 3, 2006; Accepted February 27, 2007.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (11 May 2020). "CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions". Our World in Data.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (11 May 2020). "CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions". Our World in Data.

- ^ "Why China is struggling to wean itself from coal | Hellenic Shipping News Worldwide". www.hellenicshippingnews.com. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ Nesbit, Jeff (24 May 2021). "China finances most coal plants built today – it's a climate problem and why US-China talks are essential". The Conversation. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ Spencer,Richard "Pollution kills 750,000 in China every year" Archived 2013-11-17 at the Wayback Machine The Telegraph UK, 4 July 2007

- ^ Andrews-Speed, Philip (November 2014). "China's Energy Policymaking Processes and Their Consequences". The National Bureau of Asian Research Energy Security Report. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ^ "South China town unrest cools after dialogue" Archived 2014-01-31 at the Wayback Machine Associated Foreign Press, 23 December 2011

- ^ a b Bawden, Tom "China agrees to impose carbon targets by 2016" Archived 2017-08-27 at the Wayback Machine The Independent, 21 May 2013

- ^ "America wants China to end support for coal projects abroad". The Economist. 4 September 2021. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ Cohen, Armond (21 April 2014). "Learning from China: A Blueprint for the Future of Coal in Asia?". The National Bureau of Asian Research. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ "Chinese government demand coal companies begin to pay for bad air". Greenpeace East Asia. 26 September 2011. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Zhang, Angela Huyue (2024). High Wire: How China Regulates Big Tech and Governs Its Economy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197682258.

- ^ Chen, Kathy; Tom Miles (22 May 2015). "Beijing promises coal-free power by 2017 to fight pollution". Reuters. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Mines and Communities Website. A Burning Issue Archived 2008-02-22 at the Wayback Machine. February 14, 2003.

- ^ Xinhua. N China to put out some coalfield fires by 2012 Archived 2010-06-11 at the Wayback Machine. 2010-06-04

- ^ World Investment Report 2007: Transition Corporations, Extractive Industries United Nations Conference on Trade and Development page 149

- ^ "List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor". www.dol.gov. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ China and Coal. Archived November 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Financial Times. 750,000 a year killed by Chinese pollution Archived 2009-12-13 at the Wayback Machine. July 2, 2007.

released version of the report: [2] Archived 2008-09-04 at the Wayback Machine - ^ Xinhua. China to ban small coal mines for improving pit safety record Archived 2008-10-21 at the Wayback Machine. August 15, 2008.

- ^ a b "42 Reported Dead, and 66 Trapped, in China Mine Accident" Archived 2017-03-17 at the Wayback Machine by the Associated Press, via The New York Times. November 21, 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ International Herald Tribune. Chinese coal industry in need of a helping hand Archived 2014-08-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "China's coalmine death toll drops 7.5% in 2010". Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ "20 Die in Coal Mine Plunge – China Digital Times (CDT)". 25 September 2012. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Mines and Communities Website. China and US coal disasters Archived 2014-05-17 at the Wayback Machine. 7th January 2006.

- ^ TURKEY MINING 2018 (PDF). Global Business Reports. p. 35. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ Runyon, Jennifer (23 June 2021). "Report: New solar is cheaper to build than to run existing coal plants in China, India and most of Europe". Renewable Energy World. Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ a b "CHINA'S CARBON NEUTRAL OPPORTUNITY" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2021.

- ^ Zhan, Jing Vivian (2022). China's Contained Resource Curse: How Minerals Shape State-Capital-Labor Relations. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-04898-9.

- ^ Kahrl, Fredrich; Lin, Jiang; Liu, Xu; Hu, Junfeng (24 September 2021). "Sunsetting coal power in China". iScience. 24 (9): 102939. Bibcode:2021iSci...24j2939K. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.102939. ISSN 2589-0042. PMC 8379489. PMID 34458696.

- ^ "India and China Can Quit Coal Earlier, But the World Must Work Alongside Them". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ "Coal should play no part in post-coronavirus recoveries, U.N. chief says". Reuters. 24 July 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ "Kerry: China's Coal Binge Could 'Undo' Global Capacity to Meet Climate Targets | Voice of America – English". www.voanews.com. 2 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "In climate pledge, Xi says China will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad". Reuters. 22 September 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Ren, Mengjia; Branstetter, Lee G.; Kovak, Brian K.; Armanios, Daniel E.; Yuan, Jiahai (January 2019). "Why Has China Overinvested in Coal Power?". NBER Paper. Working Paper Series (25437). National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w25437. S2CID 169618063.

- Thomson, Elspeth (2003). The Chinese Coal Industry: An Economic History. Routledge. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010.

- Wu, Shellen Xiao (2015). Empires of Coal: Fueling China's Entry into the Modern World Order, 1860-1920. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 266 pp. ISBN 978-0-8047-9284-4.

- Boom and Bust 2021: Tracking The Global Coal Plant Pipeline (Report). Global Energy Monitor. 5 April 2021.