Permian

| Permian | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A map of Earth as it appeared 275 million years ago during the Permian Period, Cisuralian Epoch | |||||||||||||

| Chronology | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Etymology | |||||||||||||

| Name formality | Formal | ||||||||||||

| Usage information | |||||||||||||

| Regional usage | Global (ICS) | ||||||||||||

| Time scale(s) used | ICS Time Scale | ||||||||||||

| Definition | |||||||||||||

| Chronological unit | Period | ||||||||||||

| Stratigraphic unit | System | ||||||||||||

| Time span formality | Formal | ||||||||||||

| Lower boundary definition | FAD of the Conodont Streptognathodus isolatus within the morphotype Streptognathodus wabaunsensis chronocline. | ||||||||||||

| Lower boundary GSSP | Aidaralash, Ural Mountains, Kazakhstan 50°14′45″N 57°53′29″E / 50.2458°N 57.8914°E | ||||||||||||

| Lower GSSP ratified | 1996[2] | ||||||||||||

| Upper boundary definition | FAD of the Conodont Hindeodus parvus. | ||||||||||||

| Upper boundary GSSP | Meishan, Zhejiang, China 31°04′47″N 119°42′21″E / 31.0798°N 119.7058°E | ||||||||||||

| Upper GSSP ratified | 2001[3] | ||||||||||||

The Permian (/ˈpɜːrmi.ən/ PUR-mee-ən)[4] is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period 298.9 million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the sixth and last period of the Paleozoic Era; the following Triassic Period belongs to the Mesozoic Era. The concept of the Permian was introduced in 1841 by geologist Sir Roderick Murchison, who named it after the region of Perm in Russia.[5][6][7][8][9]

The Permian witnessed the diversification of the two groups of amniotes, the synapsids and the sauropsids (reptiles). The world at the time was dominated by the supercontinent Pangaea, which had formed due to the collision of Euramerica and Gondwana during the Carboniferous. Pangaea was surrounded by the superocean Panthalassa. The Carboniferous rainforest collapse left behind vast regions of desert within the continental interior.[10] Amniotes, which could better cope with these drier conditions, rose to dominance in place of their amphibian ancestors.

Various authors recognise at least three,[11] and possibly four[12] extinction events in the Permian. The end of the Early Permian (Cisuralian) saw a major faunal turnover, with most lineages of primitive "pelycosaur" synapsids becoming extinct, being replaced by more advanced therapsids. The end of the Capitanian Stage of the Permian was marked by the major Capitanian mass extinction event,[13] associated with the eruption of the Emeishan Traps. The Permian (along with the Paleozoic) ended with the Permian–Triassic extinction event (colloquially known as the Great Dying), the largest mass extinction in Earth's history (which is the last of the three or four crises that occurred in the Permian), in which nearly 81% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial species died out, associated with the eruption of the Siberian Traps. It took well into the Triassic for life to recover from this catastrophe;[14][15][16] on land, ecosystems took 30 million years to recover.[17]

Etymology and history

[edit]Prior to the introduction of the term Permian, rocks of equivalent age in Germany had been named the Rotliegend and Zechstein, and in Great Britain as the New Red Sandstone.[18]

The term Permian was introduced into geology in 1841 by Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, president of the Geological Society of London, after extensive Russian explorations undertaken with Édouard de Verneuil in the vicinity of the Ural Mountains in the years 1840 and 1841. Murchison identified "vast series of beds of marl, schist, limestone, sandstone and conglomerate" that succeeded Carboniferous strata in the region.[19][20] Murchison, in collaboration with Russian geologists,[21] named the period after the surrounding Russian region of Perm, which takes its name from the medieval kingdom of Permia that occupied the same area hundreds of years prior, and which is now located in the Perm Krai administrative region.[22] Between 1853 and 1867, Jules Marcou recognised Permian strata in a large area of North America from the Mississippi River to the Colorado River and proposed the name Dyassic, from Dyas and Trias, though Murchison rejected this in 1871.[23] The Permian system was controversial for over a century after its original naming, with the United States Geological Survey until 1941 considering the Permian a subsystem of the Carboniferous equivalent to the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian.[18]

Geology

[edit]The Permian Period is divided into three epochs, from oldest to youngest, the Cisuralian, Guadalupian, and Lopingian. Geologists divide the rocks of the Permian into a stratigraphic set of smaller units called stages, each formed during corresponding time intervals called ages. Stages can be defined globally or regionally. For global stratigraphic correlation, the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) ratify global stages based on a Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) from a single formation (a stratotype) identifying the lower boundary of the stage. The ages of the Permian, from youngest to oldest, are:[24]

| Epoch | Stage | Lower boundary (Ma) |

|---|---|---|

| Early Triassic | Induan | 251.902 ±0.024 |

| Lopingian | Changhsingian | 254.14 ±0.07 |

| Wuchiapingian | 259.51 ±0.21 | |

| Guadalupian | Capitanian | 264.28 ±0.16 |

| Wordian | 266.9 ±0.4 | |

| Roadian | 273.01 ±0.14 | |

| Cisuralian | Kungurian | 283.5 ±0.6 |

| Artinskian | 290.1 ±0.26 | |

| Sakmarian | 293.52 ±0.17 | |

| Asselian | 298.9 ±0.15 |

For most of the 20th century, the Permian was divided into the Early and Late Permian, with the Kungurian being the last stage of the Early Permian.[25] Glenister and colleagues in 1992 proposed a tripartite scheme, advocating that the Roadian-Capitanian was distinct from the rest of the Late Permian, and should be regarded as a separate epoch.[26] The tripartite split was adopted after a formal proposal by Glenister et al. (1999).[27]

Historically, most marine biostratigraphy of the Permian was based on ammonoids; however, ammonoid localities are rare in Permian stratigraphic sections, and species characterise relatively long periods of time. All GSSPs for the Permian are based around the first appearance datum of specific species of conodont, an enigmatic group of jawless chordates with hard tooth-like oral elements. Conodonts are used as index fossils for most of the Palaeozoic and the Triassic.[28]

Cisuralian

[edit]The Cisuralian Series is named after the strata exposed on the western slopes of the Ural Mountains in Russia and Kazakhstan. The name was proposed by J. B. Waterhouse in 1982 to comprise the Asselian, Sakmarian, and Artinskian stages. The Kungurian was later added to conform to the Russian "Lower Permian". Albert Auguste Cochon de Lapparent in 1900 had proposed the "Uralian Series", but the subsequent inconsistent usage of this term meant that it was later abandoned.[29]

The Asselian was named by the Russian stratigrapher V.E. Ruzhenchev in 1954, after the Assel River in the southern Ural Mountains. The GSSP for the base of the Asselian is located in the Aidaralash River valley near Aqtöbe, Kazakhstan, which was ratified in 1996. The beginning of the stage is defined by the first appearance of Streptognathodus postfusus.[30]

The Sakmarian is named in reference to the Sakmara River in the southern Urals, and was coined by Alexander Karpinsky in 1874. The GSSP for the base of the Sakmarian is located at the Usolka section in the southern Urals, which was ratified in 2018. The GSSP is defined by the first appearance of Sweetognathus binodosus.[31]

The Artinskian was named after the city of Arti in Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russia. It was named by Karpinsky in 1874. The Artinskian currently lacks a defined GSSP.[24] The proposed definition for the base of the Artinskian is the first appearance of Sweetognathus aff. S. whitei.[28]

The Kungurian takes its name after Kungur, a city in Perm Krai. The stage was introduced by Alexandr Antonovich Stukenberg in 1890. The Kungurian currently lacks a defined GSSP.[24] Recent proposals have suggested the appearance of Neostreptognathodus pnevi as the lower boundary.[28]

Guadalupian

[edit]The Guadalupian Series is named after the Guadalupe Mountains in Texas and New Mexico, where extensive marine sequences of this age are exposed. It was named by George Herbert Girty in 1902.[32]

The Roadian was named in 1968 in reference to the Road Canyon Member of the Word Formation in Texas.[32] The GSSP for the base of the Roadian is located 42.7m above the base of the Cutoff Formation in Stratotype Canyon, Guadalupe Mountains, Texas, and was ratified in 2001. The beginning of the stage is defined by the first appearance of Jinogondolella nankingensis.[28]

The Wordian was named in reference to the Word Formation by Johan August Udden in 1916, Glenister and Furnish in 1961 was the first publication to use it as a chronostratigraphic term as a substage of the Guadalupian Stage.[32] The GSSP for the base of the Wordian is located in Guadalupe Pass, Texas, within the sediments of the Getaway Limestone Member of the Cherry Canyon Formation, which was ratified in 2001. The base of the Wordian is defined by the first appearance of the conodont Jinogondolella aserrata.[28]

The Capitanian is named after the Capitan Reef in the Guadalupe Mountains of Texas, named by George Burr Richardson in 1904, and first used in a chronostratigraphic sense by Glenister and Furnish in 1961 as a substage of the Guadalupian Stage.[32] The Capitanian was ratified as an international stage by the ICS in 2001. The GSSP for the base of the Capitanian is located at Nipple Hill in the southeast Guadalupe Mountains of Texas, and was ratified in 2001, the beginning of the stage is defined by the first appearance of Jinogondolella postserrata.[28]

Lopingian

[edit]The Lopingian was first introduced by Amadeus William Grabau in 1923 as the "Loping Series" after Leping, Jiangxi, China. Originally used as a lithostraphic unit, T.K. Huang in 1932 raised the Lopingian to a series, including all Permian deposits in South China that overlie the Maokou Limestone. In 1995, a vote by the Subcommission on Permian Stratigraphy of the ICS adopted the Lopingian as an international standard chronostratigraphic unit.[33]

The Wuchiapinginan and Changhsingian were first introduced in 1962, by J. Z. Sheng as the "Wuchiaping Formation" and "Changhsing Formation" within the Lopingian series. The GSSP for the base of the Wuchiapingian is located at Penglaitan, Guangxi, China and was ratified in 2004. The boundary is defined by the first appearance of Clarkina postbitteri postbitteri[33] The Changhsingian was originally derived from the Changxing Limestone, a geological unit first named by the Grabau in 1923, ultimately deriving from Changxing County, Zhejiang .The GSSP for the base of the Changhsingian is located 88 cm above the base of the Changxing Limestone in the Meishan D section, Zhejiang, China and was ratified in 2005, the boundary is defined by the first appearance of Clarkina wangi.[34]

The GSSP for the base of the Triassic is located at the base of Bed 27c at the Meishan D section, and was ratified in 2001. The GSSP is defined by the first appearance of the conodont Hindeodus parvus.[35]

Regional stages

[edit]The Russian Tatarian Stage includes the Lopingian, Capitanian and part of the Wordian, while the underlying Kazanian includes the rest of the Wordian as well as the Roadian.[25] In North America, the Permian is divided into the Wolfcampian (which includes the Nealian and the Lenoxian stages); the Leonardian (Hessian and Cathedralian stages); the Guadalupian; and the Ochoan, corresponding to the Lopingian.[36][37]

Paleogeography

[edit]

During the Permian, all the Earth's major landmasses were collected into a single supercontinent known as Pangaea, with the microcontinental terranes of Cathaysia to the east. Pangaea straddled the equator and extended toward the poles, with a corresponding effect on ocean currents in the single great ocean ("Panthalassa", the "universal sea"), and the Paleo-Tethys Ocean, a large ocean that existed between Asia and Gondwana. The Cimmeria continent rifted away from Gondwana and drifted north to Laurasia, causing the Paleo-Tethys Ocean to shrink. A new ocean was growing on its southern end, the Neotethys Ocean, an ocean that would dominate much of the Mesozoic Era.[38] A magmatic arc, containing Hainan on its southwesternmost end, began to form as Panthalassa subducted under the southeastern South China.[39] The Central Pangean Mountains, which began forming due to the collision of Laurasia and Gondwana during the Carboniferous, reached their maximum height during the early Permian around 295 million years ago, comparable to the present Himalayas, but became heavily eroded as the Permian progressed.[40] The Kazakhstania block collided with Baltica during the Cisuralian, while the North China Craton, the South China Block and Indochina fused to each other and Pangea by the end of the Permian.[41] The Zechstein Sea, a hypersaline epicontinental sea, existed in what is now northwestern Europe.[42]

Large continental landmass interiors experience climates with extreme variations of heat and cold ("continental climate") and monsoon conditions with highly seasonal rainfall patterns. Deserts seem to have been widespread on Pangaea.[43] Such dry conditions favored gymnosperms, plants with seeds enclosed in a protective cover, over plants such as ferns that disperse spores in a wetter environment. The first modern trees (conifers, ginkgos and cycads) appeared in the Permian.

Three general areas are especially noted for their extensive Permian deposits—the Ural Mountains (where Perm itself is located), China, and the southwest of North America, including the Texas red beds. The Permian Basin in the U.S. states of Texas and New Mexico is so named because it has one of the thickest deposits of Permian rocks in the world.[44]

Paleoceanography

[edit]Sea levels dropped slightly during the earliest Permian (Asselian). The sea level was stable at several tens of metres above present during the Early Permian, but there was a sharp drop beginning during the Roadian, culminating in the lowest sea level of the entire Palaeozoic at around present sea level during the Wuchiapingian, followed by a slight rise during the Changhsingian.[45]

Climate

[edit]

The Permian was cool in comparison to most other geologic time periods, with modest pole to Equator temperature gradients. At the start of the Permian, the Earth was still in the Late Paleozoic icehouse (LPIA), which began in the latest Devonian and spanned the entire Carboniferous period, with its most intense phase occurring during the latter part of the Pennsylvanian epoch.[46][47] A significant trend of increasing aridification can be observed over the course of the Cisuralian.[48] Early Permian aridification was most notable in Pangaean localities at near-equatorial latitudes.[49] Sea levels also rose notably in the Early Permian as the LPIA slowly waned.[50][51] At the Carboniferous-Permian boundary, a warming event occurred.[52] In addition to becoming warmer, the climate became notably more arid at the end of the Carboniferous and beginning of the Permian.[53][54] Nonetheless, temperatures continued to cool during most of the Asselian and Sakmarian, during which the LPIA peaked.[47][46] By 287 million years ago, temperatures warmed and the South Pole ice cap retreated in what was known as the Artinskian Warming Event (AWE),[55] though glaciers remained present in the uplands of eastern Australia,[46][56] and perhaps also the mountainous regions of far northern Siberia.[57] Southern Africa also retained glaciers during the late Cisuralian in upland environments.[58] The AWE also witnessed aridification of a particularly great magnitude.[55]

In the late Kungurian, cooling resumed,[59] resulting in a cool glacial interval that lasted into the early Capitanian,[60] though average temperatures were still much higher than during the beginning of the Cisuralian.[56] Another cool period began around the middle Capitanian.[60] This cool period, lasting for 3-4 Myr, was known as the Kamura Event.[61] It was interrupted by the Emeishan Thermal Excursion in the late part of the Capitanian, around 260 million years ago, corresponding to the eruption of the Emeishan Traps.[62] This interval of rapid climate change was responsible for the Capitanian mass extinction event.[13]

During the early Wuchiapingian, following the emplacement of the Emeishan Traps, global temperatures declined as carbon dioxide was weathered out of the atmosphere by the large igneous province's emplaced basalts.[63] The late Wuchiapingian saw the finale of the Late Palaeozoic Ice Age, when the last Australian glaciers melted.[46] The end of the Permian is marked by a temperature excursion, much larger than the Emeishan Thermal Excursion, at the Permian-Triassic boundary, corresponding to the eruption of the Siberian Traps, which released more than 5 teratonnes of CO2, more than doubling the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration.[47] A -2% δ18O excursion signifies the extreme magnitude of this climatic shift.[64] This extremely rapid interval of greenhouse gas release caused the Permian-Triassic mass extinction,[65] as well as ushering in an extreme hothouse that persisted for several million years into the next geologic epoch, the Triassic.[66]

The Permian climate was also extremely seasonal and characterised by megamonsoons,[67] which produced high aridity and extreme seasonality in Pangaea's interiors.[68] Precipitation along the western margins of the Palaeo-Tethys Ocean was very high.[69] Evidence for the megamonsoon includes the presence of megamonsoonal rainforests in the Qiangtang Basin of Tibet,[70] enormous seasonal variation in sedimentation, bioturbation, and ichnofossil deposition recorded in sedimentary facies in the Sydney Basin,[71] and palaeoclimatic models of the Earth's climate based on the behaviour of modern weather patterns showing that such a megamonsoon would occur given the continental arrangement of the Permian.[72] The aforementioned increasing equatorial aridity was likely driven by the development and intensification of this Pangaean megamonsoon.[73]

Life

[edit]

Marine biota

[edit]Permian marine deposits are rich in fossil mollusks,[74] brachiopods,[75][76][77] and echinoderms.[78][79] Brachiopods were highly diverse during the Permian. The extinct order Productida was the predominant group of Permian brachiopods, accounting for up to about half of all Permian brachiopod genera.[80] Brachiopods also served as important ecosystem engineers in Permian reef complexes.[81] Amongst ammonoids, Goniatitida were a major group during the Early-Mid Permian, but declined during the Late Permian. Members of the order Prolecanitida were less diverse. The Ceratitida originated from the family Daraelitidae within Prolecanitida during the mid-Permian, and extensively diversified during the Late Permian.[82] Only three families of trilobite are known from the Permian, Proetidae, Brachymetopidae and Phillipsiidae. Diversity, origination and extinction rates during the Early Permian were low. Trilobites underwent a diversification during the Kungurian-Wordian, the last in their evolutionary history, before declining during the Late Permian. By the Changhsingian, only a handful (4-6) genera remained.[83] Corals exhibited a decline in diversity over the course of the Middle and Late Permian.[84]

Terrestrial biota

[edit]Terrestrial life in the Permian included diverse plants, fungi, arthropods, and various types of tetrapods. The period saw a massive desert covering the interior of Pangaea. The warm zone spread in the northern hemisphere, where extensive dry desert appeared.[85] The rocks formed at that time were stained red by iron oxides, the result of intense heating by the sun of a surface devoid of vegetation cover. A number of older types of plants and animals died out or became marginal elements.

The Permian began with the Carboniferous flora still flourishing. About the middle of the Permian a major transition in vegetation began. The swamp-loving lycopod trees of the Carboniferous, such as Lepidodendron and Sigillaria, were progressively replaced in the continental interior by the more advanced seed ferns and early conifers as a result of the Carboniferous rainforest collapse. At the close of the Permian, lycopod and equisete swamps reminiscent of Carboniferous flora survived only in Cathaysia, a series of equatorial islands in the Paleo-Tethys Ocean that later would become South China.[86]

The Permian saw the radiation of many important conifer groups, including the ancestors of many present-day families. Rich forests were present in many areas, with a diverse mix of plant groups. The southern continent saw extensive seed fern forests of the Glossopteris flora. Oxygen levels were probably high there. The ginkgos and cycads also appeared during this period.

Insects

[edit]

Insects, which had first appeared and become abundant during the preceding Carboniferous, experienced a dramatic increase in diversification during the Early Permian. Towards the end of the Permian, there was a substantial drop in both origination and extinction rates.[87] The dominant insects during the Permian Period were early representatives of Paleoptera, Polyneoptera, and Paraneoptera. Palaeodictyopteroidea, which had represented the dominant group of insects during the Carboniferous, declined during the Permian. This is likely due to competition by Hemiptera, due to their similar mouthparts and therefore ecology. Primitive relatives of damselflies and dragonflies (Meganisoptera), which include the largest flying insects of all time, also declined during the Permian.[88] Holometabola, the largest group of modern insects, also diversified during this time.[87] "Grylloblattidans", an extinct group of winged insects thought to be related to modern ice crawlers, reached their apex of diversity during the Permian, representing up to a third of all insects at some localities.[89] Mecoptera (sometimes known as scorpionflies) first appeared during the Early Permian, going on to become diverse during the Late Permian. Some Permian mecopterans, like Mesopsychidae have long proboscis that suggest they may have pollinated gymnosperms.[90] The earliest known beetles appeared at the beginning of the Permian. Early beetles such as members of Permocupedidae were likely xylophagous, feeding on decaying wood. Several lineages such as Schizophoridae expanded into aquatic habitats by the Late Permian.[91] Members of the modern orders Archostemata and Adephaga are known from the Late Permian.[92][93] Complex wood boring traces found in the Late Permian of China suggest that members of Polyphaga, the most diverse group of modern beetles, were also present by the Late Permian.[94]

Tetrapods

[edit]

The terrestrial fossil record of the Permian is patchy and temporally discontinuous. Early Permian records are dominated by equatorial Europe and North America, while those of the Middle and Late Permian are dominated by temperate Karoo Supergroup sediments of South Africa and the Ural region of European Russia.[95] Early Permian terrestrial faunas of North America and Europe were dominated by primitive pelycosaur synapsids including the herbivorous edaphosaurids, and carnivorous sphenacodontids, diadectids and amphibians.[96][97] Early Permian reptiles, such as acleistorhinids, were mostly small insectivores.[98]

Amniotes

[edit]Synapsids (the group that would later include mammals) thrived and diversified greatly during the Cisuralian. Permian synapsids included some large members such as Dimetrodon. The special adaptations of synapsids enabled them to flourish in the drier climate of the Permian and they grew to dominate the vertebrates.[96] A faunal turnover occurred around the transition between the Cisuralian and Guadalupian, with the decline of amphibians and the replacement of pelycosaurs (a paraphyletic group) with more advanced therapsids,[11] although the decline of early synapsid clades was apparently a slow event that lasted about 20 Ma, from the Sakmarian to the end of the Kungurian.[99] Predator-prey interactions among terrestrial synapsids became more dynamic.[100] If terrestrial deposition ended around the end of the Cisuralian in North America and began in Russia during the early Guadalupian, a continuous record of the transition is not preserved. Uncertain dating has led to suggestions that there is a global hiatus in the terrestrial fossil record during the late Kungurian and early Roadian, referred to as "Olson's Gap" that obscures the nature of the transition. Other proposals have suggested that the North American and Russian records overlap,[101][102][103][104] with the latest terrestrial North American deposition occurring during the Roadian, suggesting that there was an extinction event, dubbed "Olson's Extinction".[105] The Middle Permian faunas of South Africa and Russia are dominated by therapsids, most abundantly by the diverse Dinocephalia. Dinocephalians become extinct at the end of the Middle Permian, during the Capitanian mass extinction event. Late Permian faunas are dominated by advanced therapsids such as the predatory sabertoothed gorgonopsians and herbivorous beaked dicynodonts, alongside large herbivorous pareiasaur parareptiles.[106] The Archosauromorpha, the group of reptiles that would give rise to the pseudosuchians, dinosaurs, and pterosaurs in the following Triassic, first appeared and diversified during the Late Permian, including the first appearance of the Archosauriformes during the latest Permian.[107] Cynodonts, the group of therapsids ancestral to modern mammals, first appeared and gained a worldwide distribution during the Late Permian.[108] Another group of therapsids, the therocephalians (such as Lycosuchus), arose in the Middle Permian.[109][110] There were no flying vertebrates, though the extinct lizard-like reptile family Weigeltisauridae from the Late Permian had extendable wings like modern gliding lizards, and are the oldest known gliding vertebrates.[111][112]

-

Edaphosaurus pogonias and Platyhystrix – Early Permian, North America and Europe

-

Dimetrodon grandis and Eryops – Early Permian, North America

-

Ocher fauna, Estemmenosuchus uralensis and Eotitanosuchus – Middle Permian, Ural Region

-

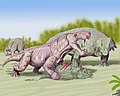

Titanophoneus and Ulemosaurus – Ural Region

-

Inostrancevia alexandri and Scutosaurus – Late Permian, North European Russia (Northern Dvina)

Amphibians

[edit]Permian stem-amniotes consisted of lepospondyli and batrachosaurs, according to some phylogenies;[113] according to others, stem-amniotes are represented only by diadectomorphs.[114]

Temnospondyls reached a peak of diversity in the Cisuralian, with a substantial decline during the Guadalupian-Lopingian following Olson's extinction, with the family diversity dropping below Carboniferous levels.[115]

Embolomeres, a group of aquatic crocodile-like limbed vertebrates that are reptilliomorphs under some phylogenies. They previously had their last records in the Cisuralian, are now known to have persisted into the Lopingian in China.[116]

Modern amphibians (lissamphibians) are suggested to have originated during Permian, descending from a lineage of dissorophoid temnospondyls[117] or lepospondyls.[114]

Fish

[edit]The diversity of fish during the Permian is relatively low compared to the following Triassic. The dominant group of bony fishes during the Permian were the "Paleopterygii" a paraphyletic grouping of Actinopterygii that lie outside of Neopterygii.[118] The earliest unequivocal members of Neopterygii appear during the Early Triassic, but a Permian origin is suspected.[119] The diversity of coelacanths is relatively low throughout the Permian in comparison to other marine fishes, though there is an increase in diversity during the terminal Permian (Changhsingian), corresponding with the highest diversity in their evolutionary history during the Early Triassic.[118] Diversity of freshwater fish faunas was generally low and dominated by lungfish and "Paleopterygians".[118] The last common ancestor of all living lungfish is thought to have existed during the Early Permian. Though the fossil record is fragmentary, lungfish appear to have undergone an evolutionary diversification and size increase in freshwater habitats during the Early Permian, but subsequently declined during the middle and late Permian.[120] Conodonts experienced their lowest diversity of their entire evolutionary history during the Permian.[121] Permian chondrichthyan faunas are poorly known.[122] Members of the chondrichthyan clade Holocephali, which contains living chimaeras, reached their apex of diversity during the Carboniferous-Permian, the most famous Permian representative being the "buzz-saw shark" Helicoprion, known for its unusual spiral shaped spiral tooth whorl in the lower jaw.[123] Hybodonts, a group of shark-like chondrichthyans, were widespread and abundant members of marine and freshwater faunas throughout the Permian.[122][124] Xenacanthiformes, another extinct group of shark-like chondrichthyans, were common in freshwater habitats, and represented the apex predators of freshwater ecosystems.[125]

Flora

[edit]

Four floristic provinces in the Permian are recognised, the Angaran, Euramerican, Gondwanan, and Cathaysian realms.[126] The Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse would result in the replacement of lycopsid-dominated forests with tree-fern dominated ones during the late Carboniferous in Euramerica, and result in the differentiation of the Cathaysian floras from those of Euramerica.[126] The Gondwanan floristic region was dominated by Glossopteridales, a group of woody gymnosperm plants, for most of the Permian, extending to high southern latitudes. The ecology of the most prominent glossopterid, Glossopteris, has been compared to that of bald cypress, living in mires with waterlogged soils.[127] The tree-like calamites, distant relatives of modern horsetails, lived in coal swamps and grew in bamboo-like vertical thickets. A mostly complete specimen of Arthropitys from the Early Permian Chemnitz petrified forest of Germany demonstrates that they had complex branching patterns similar to modern angiosperm trees.[128] By the Late Permian, high thin forests had become widespread across the globe, as evidenced by the global distribution of weigeltisaurids.[129]

The oldest likely record of Ginkgoales (the group containing Ginkgo and its close relatives) is Trichopitys heteromorpha from the earliest Permian of France.[130] The oldest known fossils definitively assignable to modern cycads are known from the Late Permian.[131] In Cathaysia, where a wet tropical frost-free climate prevailed, the Noeggerathiales, an extinct group of tree fern-like progymnosperms were a common component of the flora[132][133] The earliest Permian (~ 298 million years ago) Cathyasian Wuda Tuff flora, representing a coal swamp community, has an upper canopy consisting of lycopsid tree Sigillaria, with a lower canopy consisting of Marattialean tree ferns, and Noeggerathiales.[126] Early conifers appeared in the Late Carboniferous, represented by primitive walchian conifers, but were replaced with more derived voltzialeans during the Permian. Permian conifers were very similar morphologically to their modern counterparts, and were adapted to stressed dry or seasonally dry climatic conditions.[128] The increasing aridity, especially at low latitudes, facilitated the spread of conifers and their increasing prevalence throughout terrestrial ecosystems.[134] Bennettitales, which would go on to become in widespread the Mesozoic, first appeared during the Cisuralian in China.[135] Lyginopterids, which had declined in the late Pennsylvanian and subsequently have a patchy fossil record, survived into the Late Permian in Cathaysia and equatorial east Gondwana.[136]

Permian–Triassic extinction event

[edit]

The Permian ended with the most extensive extinction event recorded in paleontology: the Permian–Triassic extinction event. 90 to 95% of marine species became extinct, as well as 70% of all land organisms. It is also the only known mass extinction of insects.[16][137] Recovery from the Permian–Triassic extinction event was protracted; on land, ecosystems took 30 million years to recover.[17] Trilobites, which had thrived since Cambrian times, finally became extinct before the end of the Permian. Nautiloids, a subclass of cephalopods, surprisingly survived this occurrence.

There is evidence that magma, in the form of flood basalt, poured onto the Earth's surface in what is now called the Siberian Traps, for thousands of years, contributing to the environmental stress that led to mass extinction. The reduced coastal habitat and highly increased aridity probably also contributed. Based on the amount of lava estimated to have been produced during this period, the worst-case scenario is the release of enough carbon dioxide from the eruptions to raise world temperatures five degrees Celsius.[138]

Another hypothesis involves ocean venting of hydrogen sulfide gas. Portions of the deep ocean will periodically lose all of its dissolved oxygen allowing bacteria that live without oxygen to flourish and produce hydrogen sulfide gas. If enough hydrogen sulfide accumulates in an anoxic zone, the gas can rise into the atmosphere. Oxidizing gases in the atmosphere would destroy the toxic gas, but the hydrogen sulfide would soon consume all of the atmospheric gas available. Hydrogen sulfide levels might have increased dramatically over a few hundred years. Models of such an event indicate that the gas would destroy ozone in the upper atmosphere allowing ultraviolet radiation to kill off species that had survived the toxic gas.[139] There are species that can metabolize hydrogen sulfide.

Another hypothesis builds on the flood basalt eruption theory. An increase in temperature of five degrees Celsius would not be enough to explain the death of 95% of life. But such warming could slowly raise ocean temperatures until frozen methane reservoirs below the ocean floor near coastlines melted, expelling enough methane (among the most potent greenhouse gases) into the atmosphere to raise world temperatures an additional five degrees Celsius. The frozen methane hypothesis helps explain the increase in carbon-12 levels found midway in the Permian–Triassic boundary layer. It also helps explain why the first phase of the layer's extinctions was land-based, the second was marine-based (and starting right after the increase in C-12 levels), and the third land-based again.[140]

See also

[edit]- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- Olson's Extinction

- List of Permian tetrapods

References

[edit]- ^ "International Chronostratigraphic Chart" (PDF). International Commission on Stratigraphy. September 2023. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- ^ Davydov, Vladimir; Glenister, Brian; Spinosa, Claude; Ritter, Scott; Chernykh, V.; Wardlaw, B.; Snyder, W. (March 1998). "Proposal of Aidaralash as Global Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for base of the Permian System" (PDF). Episodes. 21: 11–18. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/1998/v21i1/003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Hongfu, Yin; Kexin, Zhang; Jinnan, Tong; Zunyi, Yang; Shunbao, Wu (June 2001). "The Global Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) of the Permian-Triassic Boundary" (PDF). Episodes. 24 (2): 102–114. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2001/v24i2/004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ "Permian". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ Olroyd, D.R. (2005). "Famous Geologists: Murchison". In Selley, R.C.; Cocks, L.R.M.; Plimer, I.R. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Geology, volume 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 213. ISBN 0-12-636380-3.

- ^ Ogg, J.G.; Ogg, G.; Gradstein, F.M. (2016). A Concise Geologic Time Scale: 2016. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-444-63771-0.

- ^ Murchison, R.I.; de Verneuil, E.; von Keyserling, A. (1842). On the Geological Structure of the Central and Southern Regions of Russia in Europe, and of the Ural Mountains. London: Richard and John E. Taylor. p. 14.

Permian System. (Zechstein of Germany — Magnesian limestone of England)—Some introductory remarks explain why the authors have ventured to use a new name in reference to a group of rocks which, as a whole, they consider to be on the parallel of the Zechstein of Germany and the magnesian limestone of England. They do so, not merely because a portion of deposits has long been known by the name "grits of Perm", but because, being enormously developed in the governments of Perm and Orenburg, they there assume a great variety of lithological features ...

- ^ Murchison, R.I.; de Verneuil, E.; von Keyserling, A. (1845). Geology of Russia in Europe and the Ural Mountains. Vol. 1: Geology. London: John Murray. pp. 138–139.

...Convincing ourselves in the field, that these strata were so distinguished as to constitute a system, connected with the carboniferous rocks on the one hand, and independent of the Trias on the other, we ventured to designate them by a geographical term, derived from the ancient kingdom of Permia, within and around whose precincts the necessary evidences had been obtained. ... For these reasons, then, we were led to abandon both the German and British nomenclature, and to prefer a geographical name, taken from the region in which the beds are loaded with fossils of an independent and intermediary character; and where the order of superposition is clear, the lower strata of the group being seen to rest upon the Carboniferous rocks.

- ^ Verneuil, E. (1842). "Correspondance et communications". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 13: 11–14. pp. 12–13:

Le nom de Système Permien, nom dérivé de l'ancien royaume de Permie, aujourd'hui gouvernement de Perm, donc ce dépôt occupe une large part, semblerait assez lui convener ...

[The name of the Permian System, a name derived from the ancient kingdom of Permia, today the Government of Perm, of which this deposit occupies a large part, would seem to suit it well enough ...] - ^ Sahney, S.; Benton, M.J.; Falcon-Lang, H.J. (2010). "Rainforest collapse triggered Pennsylvanian tetrapod diversification in Euramerica". Geology. 38 (12): 1079–1082. Bibcode:2010Geo....38.1079S. doi:10.1130/G31182.1. S2CID 128642769.

- ^ a b Didier, Gilles; Laurin, Michel (9 December 2021). "Distributions of extinction times from fossil ages and tree topologies: the example of mid-Permian synapsid extinctions". PeerJ. 9: e12577. doi:10.7717/peerj.12577. PMC 8667717. PMID 34966586.

- ^ Lucas, S.G. (July 2017). "Permian tetrapod extinction events". Earth-Science Reviews. 170: 31–60. Bibcode:2017ESRv..170...31L. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.04.008.

- ^ a b Day, Michael O.; Ramezani, Jahandar; Bowring, Samuel A.; Sadler, Peter M.; Erwin, Douglas H.; Abdala, Fernando; Rubidge, Bruce S. (22 July 2015). "When and how did the terrestrial mid-Permian mass extinction occur? Evidence from the tetrapod record of the Karoo Basin, South Africa". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282 (1811): 20150834. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.0834. PMC 4528552. PMID 26156768.

- ^ Zhao, Xiaoming; Tong, Jinnan; Yao, Huazhou; Niu, Zhijun; Luo, Mao; Huang, Yunfei; Song, Haijun (1 July 2015). "Early Triassic trace fossils from the Three Gorges area of South China: Implications for the recovery of benthic ecosystems following the Permian–Triassic extinction". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 429: 100–116. Bibcode:2015PPP...429..100Z. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.04.008. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ Martindale, Rowan C.; Foster, William J.; Velledits, Felicitász (1 January 2019). "The survival, recovery, and diversification of metazoan reef ecosystems following the end-Permian mass extinction event". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 513: 100–115. Bibcode:2019PPP...513..100M. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.08.014. S2CID 135338869. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ a b "GeoKansas--Geotopics--Mass Extinctions". ku.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-09-20. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ^ a b Sahney, S.; Benton, M. J. (2008). "Recovery from the most profound mass extinction of all time". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1636): 759–65. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1370. PMC 2596898. PMID 18198148.

- ^ a b Benton, Michael J.; Sennikov, Andrey G. (2021-06-08). "The naming of the Permian System". Journal of the Geological Society. 179. doi:10.1144/jgs2021-037. ISSN 0016-7649. S2CID 235773352. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved 2021-08-18.

- ^ Benton, M.J. et al., Murchison's first sighting of the Permian, at Vyazniki in 1841 Archived 2012-03-24 at WebCite, Proceedings of the Geologists' Association, accessed 2012-02-21

- ^ Murchison, Roderick Impey (1841) "First sketch of some of the principal results of a second geological survey of Russia", Archived 2023-07-16 at the Wayback Machine Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, series 3, 19 : 417-422. From p. 419: "The carboniferous system is surmounted, to the east of the Volga, by a vast series of marls, schists, limestones, sandstones and conglomerates, to which I propose to give the name of "Permian System," … ."

- ^ Henderson, C. M.; Davydov and, V. I.; Wardlaw, B. R.; Gradstein, F. M.; Hammer, O. (2012-01-01), Gradstein, Felix M.; Ogg, James G.; Schmitz, Mark D.; Ogg, Gabi M. (eds.), "Chapter 24 - The Permian Period", The Geologic Time Scale, Boston: Elsevier, pp. 653–679, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-59425-9.00024-x, ISBN 978-0-444-59425-9, archived from the original on 2022-02-01, retrieved 2022-02-01,

In 1841, after a tour of Russia with French paleontologist Edouard de Verneuil, Roderick I. Murchison, in collabo- ration with Russian geologists, named the Permian System

- ^ Henderson, C. M.; Davydov and, V. I.; Wardlaw, B. R.; Gradstein, F. M.; Hammer, O. (2012-01-01), Gradstein, Felix M.; Ogg, James G.; Schmitz, Mark D.; Ogg, Gabi M. (eds.), "Chapter 24 - The Permian Period", The Geologic Time Scale, Boston: Elsevier, p. 654, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-59425-9.00024-x, ISBN 978-0-444-59425-9, archived from the original on 2022-02-01, retrieved 2022-02-01,

He proposed the name "Permian" based on the extensive region that composed the ancient kingdom of Permia; the city of Perm lies on the flanks of the Urals.

- ^ Henderson, C.M.; Davydov and, V.I.; Wardlaw, B.R.; Gradstein, F.M.; Hammer, O. (2012), "The Permian Period", The Geologic Time Scale, Elsevier, pp. 653–679, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-59425-9.00024-x, ISBN 978-0-444-59425-9, archived from the original on 2022-01-23, retrieved 2021-03-17

- ^ a b c Cohen, K.M., Finney, S.C., Gibbard, P.L. & Fan, J.-X. (2013; updated) The ICS International Chronostratigraphic Chart Archived 2023-05-28 at the Wayback Machine. Episodes 36: 199-204.

- ^ a b Olroyd, Savannah L.; Sidor, Christian A. (August 2017). "A review of the Guadalupian (middle Permian) global tetrapod fossil record". Earth-Science Reviews. 171: 583–597. Bibcode:2017ESRv..171..583O. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.07.001.

- ^ Glenister, Brian F.; Boyd, D. W.; Furnish, W. M.; Grant, R. E.; Harris, M. T.; Kozur, H.; Lambert, L. L.; Nassichuk, W. W.; Newell, N. D.; Pray, L. C.; Spinosa, C. (September 1992). "The Guadalupian: Proposed International Standard for a Middle Permian Series". International Geology Review. 34 (9): 857–888. Bibcode:1992IGRv...34..857G. doi:10.1080/00206819209465642. ISSN 0020-6814.

- ^ Glenister BF., Wardlaw BR., Lambert LL., Spinosa C., Bowring SA., Erwin DH., Menning M., Wilde GL. 1999. Proposal of Guadalupian and component Roadian, Wordian and Capitanian stages as international standards for the middle Permian series. Permophiles 34:3-11

- ^ a b c d e f Lucas, Spencer G.; Shen, Shu-Zhong (2018). "The Permian timescale: an introduction". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 450 (1): 1–19. Bibcode:2018GSLSP.450....1L. doi:10.1144/SP450.15. ISSN 0305-8719.

- ^ Gradstein, Felix M.; Ogg, James G.; Smith, Alan G. (2004). A geologic time scale 2004. Cambridge University Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-521-78673-7. Archived from the original on 2023-07-16. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ^ Davydov, V.I., Glenister, B.F., Spinosa, C., Ritter, S.M., Chernykh, V.V., Wardlaw, B.R. & Snyder, W.S. 1998. Proposal of Aidaralash as Global Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for base of the Permian System Archived 2021-04-16 at the Wayback Machine. Episodes, 21, 11–17.

- ^ Chernykh, by Valery V.; Chuvashov, Boris I.; Shen, Shu-Zhong; Henderson, Charles M.; Yuan, Dong-Xun; Stephenson, and Michael H. (2020-12-01). "The Global Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the base- Sakmarian Stage (Cisuralian, Lower Permian)". Episodes. 43 (4): 961–979. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2020/020059.

- ^ a b c d Glenister, B.F., Wardlaw, B.R. et al. 1999. Proposal of Guadalupian and component Roadian, Wordian and Capitanian stages as international standards for the middle Permian series Archived 2021-04-16 at the Wayback Machine. Permophiles, 34, 3–11.

- ^ a b Jin, Y.; Shen, S.; Henderson, C. M.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Cao, C. & Shang, Q.; 2006: The Global Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the boundary between the Capitanian and Wuchiapingian Stage (Permian) Archived 2021-08-28 at the Wayback Machine, Episodes 29(4), pp. 253–262

- ^ Jin, Yugan; Wang, Yue; Henderson, Charles; Wardlaw, Bruce R.; Shen, Shuzhong; Cao, Changqun (2006-09-01). "The Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the base of Changhsingian Stage (Upper Permian)". Episodes. 29 (3): 175–182. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2006/v29i3/003. ISSN 0705-3797.

- ^ Hongfu, Yin; Kexin, Zhang; Jinnan, Tong; Zunyi, Yang; Shunbao, Wu (June 2001). "The Global Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) of the Permian-Triassic Boundary" (PDF). Episodes. 24 (2): 102–114. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2001/v24i2/004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ Ross, C. A.; Ross, June R. P. (1995). "Permian Sequence Stratigraphy". The Permian of Northern Pangea. pp. 98–123. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-78593-1_7. ISBN 978-3-642-78595-5.

- ^ "Permian: Stratigraphy". UC Museum of Paleontology. University of California Berkeley. Archived from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ Scotese, C. R.; Langford, R. P. (1995). "Pangea and the Paleogeography of the Permian". The Permian of Northern Pangea. pp. 3–19. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-78593-1_1. ISBN 978-3-642-78595-5.

- ^ Hu, Lisha; Cawood, Peter A.; Du, Yuansheng; Xu, Yajun; Wang, Chenghao; Wang, Zhiwen; Ma, Qianli; Xu, Xinran (1 November 2017). "Permo-Triassic detrital records of South China and implications for the Indosinian events in East Asia". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 485: 84–100. Bibcode:2017PPP...485...84H. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.06.005. hdl:10023/14143. ISSN 0031-0182. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ Scotese, C.R.; Schettino, A. (2017), "Late Permian-Early Jurassic Paleogeography of Western Tethys and the World", Permo-Triassic Salt Provinces of Europe, North Africa and the Atlantic Margins, Elsevier, pp. 57–95, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-809417-4.00004-5, ISBN 978-0-12-809417-4, archived from the original on 2021-10-05, retrieved 2021-03-15

- ^ Liu, Jun; Yi, Jian; Chen, Jian-Ye (August 2020). "Constraining assembly time of some blocks on eastern margin of Pangea using Permo-Triassic non-marine tetrapod records". Earth-Science Reviews. 207: 103215. Bibcode:2020ESRv..20703215L. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103215. S2CID 219766796. Archived from the original on 2022-03-09. Retrieved 2021-08-29.

- ^ Radax, Christian; Gruber, Claudia; Stan-Lotter, Helga (August 2001). "Novel haloarchaeal 16S rRNA gene sequences from Alpine Permo-Triassic rock salt". Extremophiles. 5 (4): 221–228. doi:10.1007/s007920100192. PMID 11523891. S2CID 1836320. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ Parrish, J. T. (1995). "Geologic Evidence of Permian Climate". The Permian of Northern Pangea. pp. 53–61. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-78593-1_4. ISBN 978-3-642-78595-5.

- ^ Hills, John M. (1972). "Late Paleozoic Sedimentation in West Texas Permian Basin". AAPG Bulletin. 56 (12): 2302–2322. doi:10.1306/819A421C-16C5-11D7-8645000102C1865D.

- ^ Haq, B. U.; Schutter, S. R. (3 October 2008). "A Chronology of Paleozoic Sea-Level Changes". Science. 322 (5898): 64–68. Bibcode:2008Sci...322...64H. doi:10.1126/science.1161648. PMID 18832639. S2CID 206514545.

- ^ a b c d Rosa, Eduardo L. M.; Isbell, John L. (2021). "Late Paleozoic Glaciation". In Alderton, David; Elias, Scott A. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Geology (2nd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 534–545. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-102908-4.00063-1. ISBN 978-0-08-102909-1. S2CID 226643402. Archived from the original on 2023-01-28. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- ^ a b c Scotese, Christopher R.; Song, Haijun; Mills, Benjamin J.W.; van der Meer, Douwe G. (April 2021). "Phanerozoic paleotemperatures: The earth's changing climate during the last 540 million years". Earth-Science Reviews. 215: 103503. Bibcode:2021ESRv..21503503S. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103503. ISSN 0012-8252. S2CID 233579194. Archived from the original on 7 September 2021. Alt URL Archived 2022-01-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mujal, Eudald; Fortuny, Josep; Marmi, Josep; Dinarès-Turell, Jaume; Bolet, Arnau; Oms, Oriol (January 2018). "Aridification across the Carboniferous–Permian transition in central equatorial Pangea: The Catalan Pyrenean succession (NE Iberian Peninsula)". Sedimentary Geology. 363: 48–68. Bibcode:2018SedG..363...48M. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2017.11.005. S2CID 133713470. Archived from the original on 30 October 2022. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ Tabor, Neil J.; Poulsen, Christopher J. (24 October 2008). "Palaeoclimate across the Late Pennsylvanian–Early Permian tropical palaeolatitudes: A review of climate indicators, their distribution, and relation to palaeophysiographic climate factors". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 268 (3–4): 293–310. Bibcode:2008PPP...268..293T. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.03.052. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Ma, Rui; Yang, Jianghai; Wang, Yuan; Yan, Jiaxin; Liu, Jia (1 February 2023). "Estimating the magnitude of early Permian relative sea-level changes in southern North China". Global and Planetary Change. 221: 104036. Bibcode:2023GPC...22104036M. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2023.104036. ISSN 0921-8181. S2CID 255731847. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ Yang, Wenli; Chen, Jitao; Gao, Biao; Zhong, Yutian; Huang, Xing; Wang, Yue; Qi, Yuping; Shen, Kui-Shu; Mii, Horng-Sheng; Wang, Xiang-dong; Shen, Shu-zhong (1 February 2023). "Sedimentary facies and carbon isotopes of the Upper Carboniferous to Lower Permian in South China: Implications for icehouse to greenhouse transition". Global and Planetary Change. 221: 104051. Bibcode:2023GPC...22104051Y. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2023.104051. ISSN 0921-8181. S2CID 256381624. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ Tabor, Neil J. (15 January 2007). "Permo-Pennsylvanian palaeotemperatures from Fe-Oxide and phyllosilicate δ18O values". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 253 (1): 159–171. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2006.10.024. ISSN 0012-821X. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ Michel, Lauren A.; Tabor, Neil J.; Montañez, Isabel P.; Schmitz, Mark D.; Davydov, Vladimir (15 July 2015). "Chronostratigraphy and Paleoclimatology of the Lodève Basin, France: Evidence for a pan-tropical aridification event across the Carboniferous–Permian boundary". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 430: 118–131. Bibcode:2015PPP...430..118M. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.03.020.

- ^ Tabor, Neil J.; DiMichele, William A.; Montañez, Isabel P.; Chaney, Dan S. (1 November 2013). "Late Paleozoic continental warming of a cold tropical basin and floristic change in western Pangea". International Journal of Coal Geology. 119: 177–186. Bibcode:2013IJCG..119..177T. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2013.07.009. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ a b Marchetti, Lorenzo; Forte, Giuseppa; Kustatscher, Evelyn; DiMichele, William A.; Lucas, Spencer G.; Roghi, Guido; Juncal, Manuel A.; Hartkopf-Fröder, Christoph; Krainer, Karl; Morelli, Corrado; Ronchi, Ausonio (March 2022). "The Artinskian Warming Event: an Euramerican change in climate and the terrestrial biota during the early Permian". Earth-Science Reviews. 226: 103922. Bibcode:2022ESRv..22603922M. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2022.103922. S2CID 245892961. Archived from the original on 30 October 2022. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ a b Montañez, Isabel P.; Tabor, Neil J.; Niemeier, Deb; DiMichele, William A.; Frank, Tracy D.; Fielding, Christopher R.; Isbell, John L.; Birgenheier, Lauren P.; Rygel, Michael C. (5 January 2007). "CO2-Forced Climate and Vegetation Instability During Late Paleozoic Deglaciation". Science. 315 (5808): 87–91. Bibcode:2007Sci...315...87M. doi:10.1126/science.1134207. PMID 17204648. S2CID 5757323. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ Isbell, John L.; Biakov, Alexander S.; Vedernikov, Igor L.; Davydov, Vladimir I.; Gulbranson, Erik L.; Fedorchuk, Nicholas D. (March 2016). "Permian diamictites in northeastern Asia: Their significance concerning the bipolarity of the late Paleozoic ice age". Earth-Science Reviews. 154: 279–300. Bibcode:2016ESRv..154..279I. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.01.007.

- ^ Götz, Annette E.; Hancox, P. John; Lloyd, Andrew (1 June 2020). "Southwestern Gondwana's Permian climate amelioration recorded in coal-bearing deposits of the Moatize sub-basin (Mozambique)". Palaeoworld. Carboniferous-Permian biotic and climatic events. 29 (2): 426–438. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2018.08.004. ISSN 1871-174X. S2CID 135368509. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ Korte, Christoph; Jones, Peter J.; Brand, Uwe; Mertmann, Dorothee; Veizer, Ján (4 November 2008). "Oxygen isotope values from high-latitudes: Clues for Permian sea-surface temperature gradients and Late Palaeozoic deglaciation". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 269 (1–2): 1–16. Bibcode:2008PPP...269....1K. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.06.012. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ a b Shi, G. R.; Nutman, Allen P.; Lee, Sangmin; Jones, Brian G.; Bann, Glen R. (February 2022). "Reassessing the chronostratigraphy and tempo of climate change in the Lower-Middle Permian of the southern Sydney Basin, Australia: Integrating evidence from U–Pb zircon geochronology and biostratigraphy". Lithos. 410–411: 106570. Bibcode:2022Litho.41006570S. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2021.106570. S2CID 245312062. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Isozaki, Yukio; Kawahata, Hodaka; Minoshima, Kayo (1 January 2007). "The Capitanian (Permian) Kamura cooling event: The beginning of the Paleozoic–Mesozoic transition". Palaeoworld. Contributions to Permian and Carboniferous Stratigraphy, Brachiopod Palaeontology and End-Permian Mass Extinctions, In Memory of Professor Yu-Gan Jin. 16 (1): 16–30. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2007.05.011. ISSN 1871-174X. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ Scotese, Christopher R.; Song, Haijun; Mills, Benjamin J.W.; van der Meer, Douwe G. (April 2021). "Phanerozoic paleotemperatures: The earth's changing climate during the last 540 million years". Earth-Science Reviews. 215: 103503. Bibcode:2021ESRv..21503503S. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103503. ISSN 0012-8252. S2CID 233579194. Archived from the original on 8 January 2021. Alt URL Archived 2022-01-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Yang, Jianghai; Cawood, Peter A.; Du, Yuansheng; Condon, Daniel J.; Yan, Jiaxin; Liu, Jianzhong; Huang, Yan; Yuan, Dongxun (15 June 2018). "Early Wuchiapingian cooling linked to Emeishan basaltic weathering?". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 492: 102–111. Bibcode:2018E&PSL.492..102Y. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2018.04.004. S2CID 133753596.

- ^ Chen, Bo; Joachimski, Michael M.; Shen, Shu-zhong; Lambert, Lance L.; Lai, Xu-long; Wang, Xiang-dong; Chen, Jun; Yuan, Dong-xun (1 July 2013). "Permian ice volume and palaeoclimate history: Oxygen isotope proxies revisited". Gondwana Research. 24 (1): 77–89. Bibcode:2013GondR..24...77C. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2012.07.007. ISSN 1342-937X. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ Joachimski, M. M.; Lai, X.; Shen, S.; Jiang, H.; Luo, G.; Chen, B.; Chen, J.; Sun, Y. (1 March 2012). "Climate warming in the latest Permian and the Permian-Triassic mass extinction". Geology. 40 (3): 195–198. Bibcode:2012Geo....40..195J. doi:10.1130/G32707.1. ISSN 0091-7613. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ Cao, Cheng; Bataille, Clément P.; Song, Haijun; Saltzman, Matthew R.; Tierney Cramer, Kate; Wu, Huaichun; Korte, Christoph; Zhang, Zhaofeng; Liu, Xiao-Ming (3 October 2022). "Persistent late Permian to Early Triassic warmth linked to enhanced reverse weathering". Nature Geoscience. 15 (10): 832–838. Bibcode:2022NatGe..15..832C. doi:10.1038/s41561-022-01009-x. ISSN 1752-0894. S2CID 252708876. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ Shields, Christine A.; Kiehl, Jeffrey T. (1 February 2018). "Monsoonal precipitation in the Paleo-Tethys warm pool during the latest Permian". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 491: 123–136. Bibcode:2018PPP...491..123S. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.12.001. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Ziegler, Alfred; Eshel, Gidon; Rees, P. McAllister; Rothfus, Thomas; Rowley, David; Sunderlin, David (2 January 2007). "Tracing the tropics across land and sea: Permian to present". Lethaia. 36 (3): 227–254. Bibcode:2003Letha..36..227Z. doi:10.1080/00241160310004657. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ López-Gómez, José; Arche, Alfredo; Marzo, Mariano; Durand, Marc (12 December 2005). "Stratigraphical and palaeogeographical significance of the continental sedimentary transition across the Permian–Triassic boundary in Spain". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 229 (1–2): 3–23. Bibcode:2005PPP...229....3L. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.11.028. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Fang, Xiaomin; Song, Chunhui; Yan, Maodu; Zan, Jinbo; Liu, Chenglin; Sha, Jingeng; Zhang, Weilin; Zeng, Yongyao; Wu, Song; Zhang, Dawen (September 2016). "Mesozoic litho- and magneto-stratigraphic evidence from the central Tibetan Plateau for megamonsoon evolution and potential evaporites". Gondwana Research. 37: 110–129. Bibcode:2016GondR..37..110F. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2016.05.012. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Luo, Mao; Shi, G. R.; Li, Sangmin (1 March 2020). "Stacked Parahaentzschelinia ichnofabrics from the Lower Permian of the southern Sydney Basin, southeastern Australia: Palaeoecologic and palaeoenvironmental significance". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 541: 109538. Bibcode:2020PPP...54109538L. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.109538. S2CID 214119448. Archived from the original on 6 November 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Kutzbach, J. E.; Gallimore, R. G. (20 March 1989). "Pangaean climates: Megamonsoons of the megacontinent". Journal of Geophysical Research. 94 (D3): 3341–3357. Bibcode:1989JGR....94.3341K. doi:10.1029/JD094iD03p03341. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Kessler, Jennifer L. P.; Soreghan, Gerilyn S.; Wacker, Herbert J. (1 September 2001). "Equatorial Aridity in Western Pangea: Lower Permian Loessite and Dolomitic Paleosols in Northeastern New Mexico, U.S.A." Journal of Sedimentary Research. 15 (5): 817–832. Bibcode:2001JSedR..71..817K. doi:10.1306/2DC4096B-0E47-11D7-8643000102C1865D. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Runnegar, Bruce; Newell, Norman Dennis (1971). "Caspian-like relict molluscan fauna in the South American Permian". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 146 (1). hdl:2246/1092. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ Shen, Shu-Zhong; Sun, Tian-Ren; Zhang, Yi-Chun; Yuan, Dong-Xun (December 2016). "An upper Kungurian/lower Guadalupian (Permian) brachiopod fauna from the South Qiangtang Block in Tibet and its palaeobiogeographical implications". Palaeoworld. 25 (4): 519–538. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2016.03.006. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ Torres-Martinez, M. A.; Vinn, O.; Martin-Aguilar, L. (2021). "Paleoecology of the first Devonian-like sclerobiont association on Permian brachiopods from southeastern Mexico". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 66 (1): 131–141. doi:10.4202/app.00777.2020. S2CID 232029240. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Olszewski, Thomas D.; Erwin, Douglas H. (15 April 2004). "Dynamic response of Permian brachiopod communities to long-term environmental change". Nature. 428 (6984): 738–741. Bibcode:2004Natur.428..738O. doi:10.1038/nature02464. PMID 15085129. S2CID 4396944. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ Donovan, Stephen K.; Webster, Gary D.; Waters, Johnny A. (27 September 2016). "A last peak in diversity: the stalked echinoderms of the Permian of Timor". Geology Today. 32 (5): 179–185. Bibcode:2016GeolT..32..179D. doi:10.1111/gto.12150. S2CID 132014028. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ Thompson, Jeffrey R.; Petsios, Elizabeth; Bottjer, David J. (18 April 2017). "A diverse assemblage of Permian echinoids (Echinodermata, Echinoidea) and implications for character evolution in early crown group echinoids". Journal of Paleontology. 91 (4): 767–780. Bibcode:2017JPal...91..767T. doi:10.1017/jpa.2016.158. S2CID 29250459.

- ^ Carlson, S.J. (2016). "The Evolution of Brachiopoda". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 44: 409–438. Bibcode:2016AREPS..44..409C. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-060115-012348.

- ^ Xuesong, Tian; Wei, Wang; Zhenhua, Huang; Zhiping, Zhang; Dishu, Chen (25 June 2022). "Reef-dwelling brachiopods record paleoecological and paleoenvironmental changes within the Changhsingian (late Permian) platform-margin sponge reef in eastern Sichuan Basin, China". The Anatomical Record. doi:10.1002/ar.25023. ISSN 1932-8486. PMID 35751577. S2CID 250022284. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ McGOWAN, Alistair J.; Smith, Andrew B. (May 2007). "Ammonoids Across the Permian/Triassic Boundary: A Cladistic Perspective". Palaeontology. 50 (3): 573–590. Bibcode:2007Palgy..50..573M. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00653.x. ISSN 0031-0239.

- ^ Lerosey-Aubril, Rudy; Feist, Raimund (2012), Talent, John A. (ed.), "Quantitative Approach to Diversity and Decline in Late Palaeozoic Trilobites", Earth and Life, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 535–555, doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3428-1_16, ISBN 978-90-481-3427-4, archived from the original on 2023-07-16, retrieved 2021-07-25

- ^ Wang, Xiang-Dong; Wang, Xiao-Juan (1 January 2007). "Extinction patterns of Late Permian (Lopingian) corals in China". Palaeoworld. Contributions to Permian and Carboniferous Stratigraphy, Brachiopod Palaeontology and End-Permian Mass Extinctions, In Memory of Professor Yu-Gan Jin. 16 (1): 31–38. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2007.05.009. ISSN 1871-174X. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ "The Permian Period". berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-07-04. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- ^ Xu, R. & Wang, X.-Q. (1982): Di zhi shi qi Zhongguo ge zhu yao Diqu zhi wu jing guan (Reconstructions of Landscapes in Principal Regions of China). Ke xue chu ban she, Beijing. 55 pages, 25 plates.

- ^ a b Labandeira, Conrad C. (2018-05-23), "The Fossil History of Insect Diversity", Insect Biodiversity, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 723–788, doi:10.1002/9781118945582.ch24, ISBN 978-1-118-94558-2, archived from the original on 2021-07-25, retrieved 2021-07-25

- ^ Schachat, Sandra R; Labandeira, Conrad C (2021-03-12). Dyer, Lee (ed.). "Are Insects Heading Toward Their First Mass Extinction? Distinguishing Turnover From Crises in Their Fossil Record". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 114 (2): 99–118. doi:10.1093/aesa/saaa042. ISSN 0013-8746. Archived from the original on 2021-07-25. Retrieved 2021-07-25.

- ^ Cui, Yingying; Bardin, Jérémie; Wipfler, Benjamin; Demers‐Potvin, Alexandre; Bai, Ming; Tong, Yi‐Jie; Chen, Grace Nuoxi; Chen, Huarong; Zhao, Zhen‐Ya; Ren, Dong; Béthoux, Olivier (2024-03-07). "A winged relative of ice‐crawlers in amber bridges the cryptic extant Xenonomia and a rich fossil record". Insect Science. doi:10.1111/1744-7917.13338. ISSN 1672-9609.

- ^ Lin, Xiaodan; Shih, Chungkun; Li, Sheng; Ren, Dong (2019-04-29), Ren, Dong; Shih, Chung Kun; Gao, Taiping; Yao, Yunzhi (eds.), "Mecoptera – Scorpionflies and Hangingflies", Rhythms of Insect Evolution (1 ed.), Wiley, pp. 555–595, doi:10.1002/9781119427957.ch24, ISBN 978-1-119-42798-8, retrieved 2024-09-21

- ^ Ponomarenko, A. G.; Prokin, A. A. (December 2015). "Review of paleontological data on the evolution of aquatic beetles (Coleoptera)". Paleontological Journal. 49 (13): 1383–1412. Bibcode:2015PalJ...49.1383P. doi:10.1134/S0031030115130080. ISSN 0031-0301. S2CID 88456234. Archived from the original on 2023-07-16. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- ^ Ponomarenko, A. G.; Volkov, A. N. (November 2013). "Ademosynoides asiaticus Martynov, 1936, the earliest known member of an extant beetle family (Insecta, Coleoptera, Trachypachidae)". Paleontological Journal. 47 (6): 601–606. Bibcode:2013PalJ...47..601P. doi:10.1134/s0031030113060063. ISSN 0031-0301. S2CID 84935456. Archived from the original on 2023-07-16. Retrieved 2021-07-25.

- ^ Yan, Evgeny Viktorovich; Beutel, Rolf Georg; Lawrence, John Francis; Yavorskaya, Margarita Igorevna; Hörnschemeyer, Thomas; Pohl, Hans; Vassilenko, Dmitry Vladimirovich; Bashkuev, Alexey Semenovich; Ponomarenko, Alexander Georgievich (2020-09-13). "Archaeomalthus -(Coleoptera, Archostemata) a 'ghost adult' of Micromalthidae from Upper Permian deposits of Siberia?". Historical Biology. 32 (8): 1019–1027. Bibcode:2020HBio...32.1019Y. doi:10.1080/08912963.2018.1561672. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 91721262. Archived from the original on 2019-12-15. Retrieved 2021-07-25.

- ^ Feng, Zhuo; Wang, Jun; Rößler, Ronny; Ślipiński, Adam; Labandeira, Conrad (2017-09-15). "Late Permian wood-borings reveal an intricate network of ecological relationships". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 556. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8..556F. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00696-0. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5601472. PMID 28916787.

- ^ Brocklehurst, Neil (2020-06-10). "Olson's Gap or Olson's Extinction? A Bayesian tip-dating approach to resolving stratigraphic uncertainty". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 287 (1928): 20200154. doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.0154. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 7341920. PMID 32517621.

- ^ a b Huttenlocker, A. K., and E. Rega. 2012. The Paleobiology and Bone Microstructure of Pelycosaurian-grade Synapsids. Pp. 90–119 in A. Chinsamy (ed.) Forerunners of Mammals: Radiation, Histology, Biology. Indiana University Press.

- ^ "NAPC Abstracts, Sto - Tw". berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2020-02-26. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- ^ Modesto, Sean P.; Scott, Diane M.; Reisz, Robert R. (1 July 2009). "Arthropod remains in the oral cavities of fossil reptiles support inference of early insectivory". Biology Letters. 5 (6): 838–840. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0326. PMC 2827974. PMID 19570779.

- ^ Didier, Gilles; Laurin, Michel (June 2024). "Testing extinction events and temporal shifts in diversification and fossilization rates through the skyline Fossilized Birth‐Death (FBD) model: The example of some mid‐Permian synapsid extinctions". Cladistics. 40 (3): 282–306. doi:10.1111/cla.12577. ISSN 0748-3007.

- ^ Singh, Suresh A.; Elsler, Armin; Stubbs, Thomas L.; Rayfield, Emily J.; Benton, Michael James (17 February 2024). "Predatory synapsid ecomorphology signals growing dynamism of late Palaeozoic terrestrial ecosystems". Communications Biology. 7 (1). doi:10.1038/s42003-024-05879-2. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 10874460. PMID 38368492. Retrieved 6 November 2024.

- ^ Reisz, Robert R.; Laurin, Michel (1 September 2001). "The reptile Macroleter: First vertebrate evidence for correlation of Upper Permian continental strata of North America and Russia". GSA Bulletin. 113 (9): 1229–1233. Bibcode:2001GSAB..113.1229R. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(2001)113<1229:TRMFVE>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0016-7606. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Lozovsky, Vladlen R. (1 January 2005). "Olson's gap or Olson's bridge, that is the question". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 30, The Nonmarine Permian. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science: 179–184.

- ^ Brocklehurst, Neil (10 June 2020). "Olson's Gap or Olson's Extinction? A Bayesian tip-dating approach to resolving stratigraphic uncertainty". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 287 (1928): 20200154. doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.0154. PMC 7341920. PMID 32517621. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Laurin, Michel; Hook, Robert W. (2022). "The age of North America's youngest Paleozoic continental vertebrates: a review of data from the Middle Permian Pease River (Texas) and El Reno (Oklahoma) Groups". BSGF - Earth Sciences Bulletin. 193: 10. doi:10.1051/bsgf/2022007.

- ^ Lucas, S.G. (July 2017). "Permian tetrapod extinction events". Earth-Science Reviews. 170: 31–60. Bibcode:2017ESRv..170...31L. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.04.008. Archived from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2021-04-18.

- ^ Lucas, S.G. (2017-07-01). "Permian tetrapod extinction events". Earth-Science Reviews. 170: 31–60. Bibcode:2017ESRv..170...31L. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.04.008. ISSN 0012-8252. Archived from the original on 2021-08-18. Retrieved 2021-08-18.

- ^ Spiekman, Stephan N. F.; Fraser, Nicholas C.; Scheyer, Torsten M. (2021-05-03). "A new phylogenetic hypothesis of Tanystropheidae (Diapsida, Archosauromorpha) and other "protorosaurs", and its implications for the early evolution of stem archosaurs". PeerJ. 9: e11143. doi:10.7717/peerj.11143. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 8101476. PMID 33986981.

- ^ Huttenlocker, Adam K.; Sidor, Christian A. (2020-12-01). "A Basal Nonmammaliaform Cynodont from the Permian of Zambia and the Origins of Mammalian Endocranial and Postcranial Anatomy". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40 (5): e1827413. Bibcode:2020JVPal..40E7413H. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1827413. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 228883951. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2021-08-18.

- ^ Huttenlocker A. K. (2009). "An investigation into the cladistic relationships and monophyly of therocephalian therapsids (Amniota: Synapsida)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 157 (4): 865–891. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00538.x.

- ^ Huttenlocker A. K.; Sidor C. A.; Smith R. M. H. (2011). "A new specimen of Promoschorhynchus (Therapsida: Therocephalia: Akidnognathidae) from the lowermost Triassic of South Africa and its implications for therocephalian survival across the Permo-Triassic boundary". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (2): 405–421. Bibcode:2011JVPal..31..405H. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.546720. S2CID 129242450.

- ^ Pritchard, Adam C.; Sues, Hans-Dieter; Scott, Diane; Reisz, Robert R. (20 May 2021). "Osteology, relationships and functional morphology of Weigeltisaurus jaekeli (Diapsida, Weigeltisauridae) based on a complete skeleton from the Upper Permian Kupferschiefer of Germany". PeerJ. 9: e11413. doi:10.7717/peerj.11413. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 8141288. PMID 34055483.

- ^ Bulanov, V. V.; Sennikov, A. G. (1 October 2006). "The first gliding reptiles from the upper Permian of Russia". Paleontological Journal. 40 (5): S567–S570. Bibcode:2006PalJ...40S.567B. doi:10.1134/S0031030106110037. ISSN 1555-6174. S2CID 84310001. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ Ruta, Marcello; Coates, Michael I. (January 2007). "Dates, nodes and character conflict: Addressing the Lissamphibian origin problem". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 5 (1): 69–122. Bibcode:2007JSPal...5...69R. doi:10.1017/S1477201906002008. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ^ a b Marjanović, David; Laurin, Michel (4 January 2019). "Phylogeny of Paleozoic limbed vertebrates reassessed through revision and expansion of the largest published relevant data matrix". PeerJ. 6: e5565. doi:10.7717/peerj.5565. ISSN 2167-8359. PMID 30631641.

- ^ Ruta, Marcello; Benton, Michael J. (November 2008). "Calibrated Diversity, Tree Topology and the Mother of Mass Extinctions: The Lesson of Temnospondyls". Palaeontology. 51 (6): 1261–1288. Bibcode:2008Palgy..51.1261R. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00808.x. S2CID 85411546.

- ^ Chen, Jianye; Liu, Jun (2020-12-01). "The youngest occurrence of embolomeres (Tetrapoda: Anthracosauria) from the Sunjiagou Formation (Lopingian, Permian) of North China". Fossil Record. 23 (2): 205–213. Bibcode:2020FossR..23..205C. doi:10.5194/fr-23-205-2020. ISSN 2193-0074.

- ^ Schoch, Rainer R. (January 2019). "The putative lissamphibian stem-group: phylogeny and evolution of the dissorophoid temnospondyls". Journal of Paleontology. 93 (1): 137–156. Bibcode:2019JPal...93..137S. doi:10.1017/jpa.2018.67. ISSN 0022-3360.

- ^ a b c Romano, Carlo; Koot, Martha B.; Kogan, Ilja; Brayard, Arnaud; Minikh, Alla V.; Brinkmann, Winand; Bucher, Hugo; Kriwet, Jürgen (February 2016). "Permian-Triassic Osteichthyes (bony fishes): diversity dynamics and body size evolution: Diversity and size of Permian-Triassic bony fishes". Biological Reviews. 91 (1): 106–147. doi:10.1111/brv.12161. PMID 25431138. S2CID 5332637. Archived from the original on 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2021-07-23.

- ^ Romano, Carlo (2021). "A Hiatus Obscures the Early Evolution of Modern Lineages of Bony Fishes". Frontiers in Earth Science. 8. doi:10.3389/feart.2020.618853. ISSN 2296-6463.

- ^ Kemp, Anne; Cavin, Lionel; Guinot, Guillaume (April 2017). "Evolutionary history of lungfishes with a new phylogeny of post-Devonian genera". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 471: 209–219. Bibcode:2017PPP...471..209K. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.12.051.

- ^ Ginot, Samuel; Goudemand, Nicolas (December 2020). "Global climate changes account for the main trends of conodont diversity but not for their final demise". Global and Planetary Change. 195: 103325. Bibcode:2020GPC...19503325G. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2020.103325. S2CID 225005180. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ a b Koot, Martha B.; Cuny, Gilles; Tintori, Andrea; Twitchett, Richard J. (March 2013). "A new diverse shark fauna from the Wordian (Middle Permian) Khuff Formation in the interior Haushi-Huqf area, Sultanate of Oman: CHONDRICHTHYANS FROM THE WORDIAN KHUFF FORMATION OF OMAN". Palaeontology. 56 (2): 303–343. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2012.01199.x. S2CID 86428264.

- ^ Tapanila, Leif; Pruitt, Jesse; Wilga, Cheryl D.; Pradel, Alan (2020). "Saws, Scissors, and Sharks: Late Paleozoic Experimentation with Symphyseal Dentition". The Anatomical Record. 303 (2): 363–376. doi:10.1002/ar.24046. ISSN 1932-8494. PMID 30536888. S2CID 54478736.

- ^ Peecook, Brandon R.; Bronson, Allison W.; Otoo, Benjamin K.A.; Sidor, Christian A. (November 2021). "Freshwater fish faunas from two Permian rift valleys of Zambia, novel additions to the ichthyofauna of southern Pangea". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 183: 104325. Bibcode:2021JAfES.18304325P. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2021.104325.

- ^ Kriwet, Jürgen; Witzmann, Florian; Klug, Stefanie; Heidtke, Ulrich H.J (2008-01-22). "First direct evidence of a vertebrate three-level trophic chain in the fossil record". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1631): 181–186. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1170. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 2596183. PMID 17971323.

- ^ a b c Wang, J.; Pfefferkorn, H. W.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Z. (2012-03-27). "Permian vegetational Pompeii from Inner Mongolia and its implications for landscape paleoecology and paleobiogeography of Cathaysia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (13): 4927–4932. doi:10.1073/pnas.1115076109. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3323960. PMID 22355112.

- ^ McLoughlin, S (2012). "Glossopteris – insights into the architecture and relationships of an iconic Permian Gondwanan plant". Journal of the Botanical Society of Bengal. 65 (2): 1–14.

- ^ a b Feng, Zhuo (September 2017). "Late Palaeozoic plants". Current Biology. 27 (17): R905–R909. Bibcode:2017CBio...27.R905F. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.07.041. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 28898663.

- ^ Bulanov, V. V.; Sennikov, A. G. (16 December 2010). "New data on the morphology of permian gliding weigeltisaurid reptiles of Eastern Europe". Paleontological Journal. 44 (6): 682–694. doi:10.1134/S0031030110060109. ISSN 0031-0301. Retrieved 17 July 2024 – via Springer Link.

- ^ Zhou, Zhi-Yan (March 2009). "An overview of fossil Ginkgoales". Palaeoworld. 18 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2009.01.001. Archived from the original on 2020-06-01. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ Feng, Zhuo; Lv, Yong; Guo, Yun; Wei, Hai-Bo; Kerp, Hans (November 2017). "Leaf anatomy of a late Palaeozoic cycad". Biology Letters. 13 (11): 20170456. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2017.0456. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 5719380. PMID 29093177.

- ^ Pfefferkorn, Hermann W.; Wang, Jun (April 2016). "Paleoecology of Noeggerathiales, an enigmatic, extinct plant group of Carboniferous and Permian times". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 448: 141–150. Bibcode:2016PPP...448..141P. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.11.022. Archived from the original on 2018-06-28. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ Wang, Jun; Wan, Shan; Kerp, Hans; Bek, Jiří; Wang, Shijun (March 2020). "A whole noeggerathialean plant Tingia unita Wang from the earliest Permian peat-forming flora, Wuda Coalfield, Inner Mongolia". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 294: 104204. doi:10.1016/j.revpalbo.2020.104204. S2CID 216381417. Archived from the original on 2022-10-23. Retrieved 2021-03-25.