Clark Fork River

| Clark Fork Original name given by Lewis and Clark expedition: Clark's River | |

|---|---|

The Clark Fork at Missoula, Montana | |

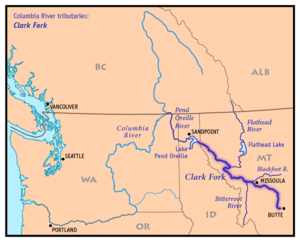

Map of the Clark Fork, its main tributaries and downriver connection to the Columbia River via the Pend Oreille River. | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Montana, Idaho |

| Cities | Butte, Missoula |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Silver Bow Creek |

| • location | Butte, Silver Bow County, Montana |

| • coordinates | 46°4′32″N 112°27′56″W / 46.07556°N 112.46556°W[1] |

| • elevation | 6,882 ft (2,098 m)[2] |

| 2nd source | Warm Springs Creek (Montana) |

| • location | Flint Creek Range, Granite County, Montana |

| • coordinates | 46°15′39″N 113°8′12″W / 46.26083°N 113.13667°W[3] |

| • elevation | 7,466 ft (2,276 m)[4] |

| Source confluence | |

| • location | Deer Lodge County, Montana |

| • coordinates | 46°11′12″N 112°46′18″W / 46.18667°N 112.77167°W[5] |

| • elevation | 4,795 ft (1,462 m)[6] |

| Mouth | Lake Pend Oreille |

• location | Bonner County, Idaho |

• coordinates | 48°11′0″N 116°16′9″W / 48.18333°N 116.26917°W[5] |

• elevation | 2,064 ft (629 m)[7] |

| Length | 310 mi (500 km)[5] |

| Basin size | 22,905 sq mi (59,320 km2)[8] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Whitehorse Rapids near Cabinet, ID[9] |

| • average | 21,930 cu ft/s (621 m3/s)[10] |

| • minimum | 762 cu ft/s (21.6 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 195,000 cu ft/s (5,500 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Bitterroot River |

| • right | Blackfoot River, Flathead River, Bull River |

The Clark Fork, or the Clark Fork of the Columbia River, is a river in the U.S. states of Montana and Idaho, approximately 310 miles (500 km) long. It is named after William Clark of the 1806 Lewis and Clark Expedition. The largest river by volume in Montana,[11] it drains an extensive region of the Rocky Mountains in western Montana and northern Idaho in the watershed of the Columbia River. The river flows northwest through a long valley at the base of the Cabinet Mountains and empties into Lake Pend Oreille in the Idaho Panhandle. The Pend Oreille River in Idaho, Washington, and British Columbia, Canada which drains the lake to the Columbia in Washington, is sometimes included as part of the Clark Fork, giving it a total length of 479 miles (771 km), with a drainage area of 25,820 square miles (66,900 km2). In its upper 20 miles (32 km) in Montana near Butte, it is known as Silver Bow Creek. Interstate 90 follows much of the upper course of the river from Butte to Saint Regis. The highest point within the river's watershed is Mount Evans at 10,641 feet (3,243 m) in Deer Lodge County, Montana along the Continental Divide.[12]

The Clark Fork is a Class I river for recreational purposes in Montana from Warm Springs Creek to the Idaho border.[13]

Description

[edit]

It rises as Silver Bow Creek[1] in southwestern Montana, less than 5 miles (8.0 km) from the Continental Divide near downtown Butte, from the confluence of Basin and Blacktail creeks. It flows northwest and north through a valley in the mountains, passing east of Anaconda, where it changes its name to the Clark Fork at the confluence with Warm Springs Creek, then northwest to Deer Lodge. Near Deer Lodge it receives the Little Blackfoot River. From Deer Lodge it flows generally northwest across western Montana, passing south of the Garnet Range toward Missoula. Five miles east of Missoula, the river receives the Blackfoot River.

Northwest of Missoula, the river continues through a long valley along the northeast flank of the Bitterroot Range, through the Lolo National Forest. It receives the Bitterroot River from the south-southwest approximately 5.5 miles (8.9 km) west of downtown Missoula. Along the Cabinet Mountains, the river receives the Flathead River from the east near Paradise. It receives the Thompson River from the north near Thompson Falls in southern Sanders County.

There are three dams on the lower Clark Fork River. At Thompson Falls, about 100 mi (160 km) northwest of Missoula, the Thompson Falls Dam, actually a series of four dams that bridge between islands in the river, was built atop the falls in 1915. Next, at Noxon, Montana, along the Cabinet Mountains and the northern end of the Bitterroots near the Idaho border, the river is impounded by the Noxon Rapids Dam, completed in 1959 and forming a 20-mile-long (32 km) reservoir. It crosses into eastern Bonner County in north Idaho between the towns of Heron, Montana and the town of Cabinet, Idaho. In Idaho, just before the town of Cabinet, the Clark Fork River is dammed again at the Cabinet Gorge Dam. The Cabinet Gorge Dam was completed in the early 1950s, and its reservoir extends eastwards into Montana.

After passing the Cabinet Gorge Dam, the river enters the northeastern end of Lake Pend Oreille, approximately 8 miles (13 km) west of the Idaho–Montana border, near the town of Clark Fork, Idaho.

History

[edit]

During the last ice age, from approximately 20,000 years ago, the Clark Fork Valley lay along the southern edge of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet covering western North America. The encroachment of the ice sheet formed an ice dam on the river, creating Glacial Lake Missoula, which stretched through the Clark Fork Valley across central Montana. The periodic rupturing and rebuilding of the ice dam released the Missoula Floods, a series of catastrophic floods down the Clark Fork and Pend Oreille into the Columbia, which sculpted many of the geographic features of eastern Washington and the Willamette Valley of Oregon.

In the 19th century, the Clark Fork Valley was inhabited by the Flathead tribe of Native Americans. It was explored by Meriwether Lewis of the Lewis and Clark Expedition during the 1806 return trip from the Pacific. The river is named for William Clark.[15] A middle segment of the river in Montana was formerly known as the Missoula River. The river was also referred to as the Deer Lodge River by Granville Stuart.

In 1809, David Thompson of the North West Company explored the region and founded several fur trading posts, including Kullyspell House at the mouth of the Clark Fork, and Saleesh House on the river near the present-day site of Thompson Falls, Montana. Thompson used the name Saleesh River for the entire Flathead-Clark Fork-Pend Oreille river system.[16] For most of the first half of the 19th century the Clark Fork river and surrounding region was controlled by the British-Canadian North West Company and Hudson's Bay Company.

In the mid-19th century, the Clark Fork River wound through the valley where cattle had replaced bison. This was when Conrad Kohrs purchased a ranch from Johnny Grant that is now called the Grant-Kohrs Ranch,[17] a National Historic Site and Federal Park. For a history of the river and the people, see Grant-Kohrs family and history of Clark Fork River region.

The Clark Fork and the Blackfoot River experienced a record flood in 1908.[18]

Since the late 19th century many areas in the watershed of the river have been extensively mined for minerals, resulting in an ongoing stream pollution problem. Most pollution has come from the copper mines in Butte and the smelter in Anaconda. Many of the most polluted areas have been designated as Superfund sites. Nevertheless, the river and its tributaries are among the most popular destinations for fly fishing in the United States.

Today, the Clark Fork watershed encompasses the largest Superfund site in America. As a mega-site, it includes three major sites: Butte, Anaconda, and Milltown Dam/Clark Fork River's Milltown Reservoir Superfund Site. Each of these major sites is split up into numerous sub-sites known as Operable Units.

Milltown Dam was removed in 2008 at the junction of the Clark Fork and Blackfoot Rivers. Stimson Dam (an old log crib dam) was removed in 2007 just upstream of the Milltown Dam on the Blackfoot River. Stimson Dam was normally under water due to the Milltown Dam. The area that used to be under Milltown Lake has recently become a State Park. Continued remediation and/or restoration of these sites is ongoing.[19]

Conservation

[edit]- "Tri-State Water Quality Council". Citizens, business, industry, tribes, government and environmental groups combined to oversee the Clark Fork-Pend Oreille river system

- "Clark Fork – Pend Oreille Conservancy". non-profit land trust serving Sanders County, Montana and Bonner County, Idaho

- "Clark Fork Coalition". The coalition was founded in 1985 and is dedicated to protecting and restoring the Clark Fork River basin.

- "Watershed Education Network (WEN)".- WEN is a 501(c)(3) organization located in Missoula, Montana. WEN is a nonprofit organization dedicated to fostering knowledge, appreciation and awareness of watershed health through science, outreach, and education. Since 1996, WEN has been dedicated to growing the next generation of watershed stewards. WEN serves over 3,000 western Montana K–12 students annually through its School Stream Monitoring Program. Stream Monitoring field trips take place at 30 different stream sites across western Montana each fall and spring.

- "Clark Fork Watershed Education Program". - The program uses outdoor activities and local experts to teach about the effects of settlement and industry on the Upper Clark Fork basin, and to give students and educators the scientific background to quantify the health of our watershed.

- Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site Riparian Restoration Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site is located within the middle of one of the largest superfund complexes in the country. The ranch contains approximately 2.44 miles of the Clark Fork River which flows through the middle of the ranch. The 2004 Record of Decision describes the cleanup approach, or Selected Remedy. In addition to the ROD, the NRDP developed a Restoration Plan to expedite the recovery time for injured aquatic and terrestrial resources in and along the Clark Fork River (Grant-Kohrs Ranch has its own Federal Restoration Plan).

See also

[edit]- Clarks Fork Yellowstone River

- Grant–Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site

- List of longest streams of Idaho

- List of rivers of Idaho

- List of rivers of Montana

- Milltown Reservoir Superfund Site

- Montana Stream Access Law

- Paradise Dam (Montana)

Further reading

[edit]- Sullivan, Gordon (2008). Saving Homewaters: The Story of Montana's Streams and Rivers. Woodstock, VT: The Countryman Press. ISBN 978-0-88150-679-2.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Silver Bow Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior., USGS GNIS.

- ^ Google Earth elevation for GNIS Silver Bow Creek source coordinates.

- ^ "Warm Springs Creek (Montana)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior., USGS GNIS.

- ^ Google Earth elevation for GNIS Warm Springs Creek source coordinates.

- ^ a b c "Clark Fork". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior., USGS GNIS.

- ^ Google Earth elevation for GNIS Clark Fork source coordinates.

- ^ Google Earth elevation for GNIS Clark Fork mouth coordinates.

- ^ "Pend Oreille subbasin overview" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-13. Retrieved 2007-05-06., Northwest Power and Conservation Council.

- ^ "Montana Water Resources Data 2004"., file "Mill Creek above Bassoo Creek, near Niarada to Clark Fork at Whitehorse Rapids, near Cabinet, ID" (PDF)..

- ^ "Montana Water Resources Data 2004"., file "Mill Creek above Bassoo Creek, near Niarada to Clark Fork at Whitehorse Rapids, near Cabinet, ID" (PDF)..

- ^ "Clark Fork Info". Clark Fork Watershed Education Program. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Mount Evans, Montana". Peakbagger. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ "Stream Access in Montana". Archived from the original on 2009-03-10.

- ^ McLean, Bryce. "Drone Shot of Clark Fork River". guide-x.io. Archived from the original on 2021-04-13. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ Rees, John E. (1918). Idaho Chronology, Nomenclature, Bibliography. W.B. Conkey Company. p. 64.

- ^ Nisbet, Jack (1994). Sources of the River: Tracking David Thompson Across Western North America. Sasquatch Books. pp. 144–145, 149, 159. ISBN 1-57061-522-5.

- ^ "Grant-Kohrs Ranch, National Historic Site". Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ "The Great Flood of 1908". Archived from the original on 2013-11-12. Retrieved 2014-01-05.

- ^ "Milltown Dam Removal & Clean up Project".

External links

[edit]- "Watershed Education Network(WEN)".

- "Clark Fork Watershed Education Program".

- "EcoRover, a blog about Superfund and other environmental issues in the upper Clark Fork River basin".

- "Clark Fork Coalition".

- "Upper Clark Fork Restoration Program". Archived from the original on 2007-06-07. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- "Clark Fork River Operable Unit – US EPA Region 8".

- "Clark Fork River Technical Assistance Committee". Archived from the original on 2014-06-30. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- "Butte Citizens Technical Environmental Committee (CTEC)".

- Rivers of Bonner County, Idaho

- Bodies of water of Deer Lodge County, Montana

- Bodies of water of Granite County, Montana

- Bodies of water of Missoula County, Montana

- Bodies of water of Silver Bow County, Montana

- Rivers of Idaho

- Rivers of Montana

- Tributaries of the Columbia River

- Environmental disasters in the United States