Cissa of Sussex

| Cissa | |

|---|---|

Artist's impression of three Saxon ships | |

| King of Sussex? | |

| Reign | 514–567? |

| Predecessor | Ælle |

| Successor | Æðelwealh |

| Issue | Unknown |

Cissa (/ˈtʃɪsɑː/) was part of an Anglo-Saxon invasion force that landed in three ships at a place called Cymensora in AD 477. The invasion was led by Cissa's father Ælle and included his two brothers. They are said to have fought against the local Britons. Their conquest of what became Sussex, England continued when they fought a battle on the margins of Mecredesburne in 485 and Pevensey in 491 where they are said to have slaughtered their opponents to the last man.

The main source for this story is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a series of annals written in the vernacular Old English. The Anglo Saxon Chronicle was commissioned in the reign of Alfred the Great some 400 years after the landing at Cymenshore. One of the purposes of the chronicle was to provide genealogies of the West Saxon kings. Although a lot of the facts provided by the chronicle can be verified, the foundation story of Sussex involving Ælle and his three sons can not. It is known that Anglo-Saxons did settle in eastern Sussex during the fifth century, but not in the west where Cymensora was probably situated.

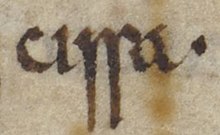

The city of Chichester, whose placename is first mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, of AD 895, is supposedly named after Cissa.

Historical attestation

[edit]The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle lists Cissa as one of the three sons of Ælle, who in the year 477 arrived in Britain at a place called Cymenshore (traditionally thought to have been in the Selsey area of Sussex[1]). The Chronicle recounts that Ælle and his three sons fought three battles: at Cymenshore in 477, one near the banks of Mercredesburne in 485 and lastly one at Pevensey in 491, where (the Chronicle claims) all Britons were slaughtered.[1][2][3][4] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was originally compiled in Winchester, the capital of Wessex, and completed in 891. It was then distributed to various monasteries throughout the country for copying. The different versions were then updated periodically. The chronicle charts Anglo-Saxon history from the mid-fifth century until 1154. Before the Norman Conquest of 1066 the manuscripts were mainly written in Old English; post-Conquest the scribes tended to use Latin.[5][6] The original Chronicle was commissioned during the rule of Alfred the Great r. 871–899 over 400 years after Cissa, and historians regard the accuracy of the events and dates listed during the fifth century as questionable.[5][6][7] The sources for the fifth century annals are obscure, however an analysis of the text demonstrates some poetic conventions, so it is probable that the narrative derived from an oral tradition, such as sagas in the form of epic poems.[4][5] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was commissioned for a number of reasons, including propaganda—it provided genealogies of the kings of Wessex, showing them in a positive light. (Wessex had absorbed the Kingdom of Sussex, founded by Ælle, during the reign of Egbert of Wessex[5] r. 802–839.)

No known archaeological evidence supports the existence of Ælle and his three sons in the Chichester or Selsey area.[8][9] The absence of early Anglo-Saxon[10] burial-grounds in the Chichester area indicates that the Saxons did not arrive there until more than a hundred years after Ælle's traditional lifetime;[9][11] Some have proposed that Chichester had an independent region of Britons (known as Sub-Roman) in the late fifth century, but no archaeological or placename evidence supports that hypothesis either.[12][13][14][15][16] Furthermore, only two early Anglo-Saxon[10] objects have been found west of the River Arun and they can be firmly dated to the sixth century, rather later than Ælle's time. One of those objects was a small long brooch from the Roman cemetery, in the St. Pancras area of Chichester.[17] Its isolation suggests that it belonged to a Saxon woman who lived and died in a British community rather than in a Saxon settlement.[18]

No written Anglo-Saxon sources claim that Cissa was ever king. The 8th-century chronicler Bede stated that Ælle was the first king to have held imperium, or overlordship, over other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, but he makes no mention of Ælle's sons.[19] The earliest source that does state that Cissa was king is that of the Anglo-Norman chronicler, Henry of Huntingdon, who wrote between 1130 and 1154, and clearly used his imagination to fill out gaps in the historical record.[20] Henry of Huntingdon derived a lot of his information from Bede. The 13th-century chronicler Roger of Wendover used Henry's work as his main source and it is probable that both Henry and Roger had access to information from manuscripts and oral sources now lost.[18][21][22] Both Henry of Huntingdon and Roger of Wendover provide extended versions of the three Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entries relating to Ælle and his sons.[22][23][24] It is assumed by both authors that Ælle was succeeded by his "son" Cissa – as is the alleged date of this "succession".[20][25][26] Roger of Wendover even went so far as to provide a death date for Cissa, that had previously been absent.[26] The date he gave was 590, which, given that Cissa is supposed to have arrived in Britain in 477, means that he must have been at least 123 years old when he died. An emendation from "died in 590", to "died aged 90" would resolve this inconsistency. As Kirby & Williams observed, "[i]t seems very unlikely that these annals in later medieval chronicles will provide a certain basis for historical reconstruction".[27]

Evidence from place names

[edit]

The early part of the Anglo Saxon Chronicle contains the frequent use of eponyms.[4][5] The chronicle's entry for 477 names Ælle's sons as Cymen, Wlenking, and Cissa.[3] All three of Ælle's 'sons' have names "which conveniently link to ancient or surviving place-names".[25] Cymenshore, the landing place where the invasion started, is named after Cymen, Lancing after Wlenking and Chichester after Cissa. Conceivably the names of Ælle's sons were derived from the place-names as the legends of the origins of the South Saxons evolved; or perhaps the legends themselves gave rise to the place-names.[1][28][29]

Another place name potentially associated with Cissa (pronounced 'Chissa') is the Iron Age hill fort Cissbury Ring, near Cissbury, which William Camden said "plainly bespeaks it the work of king Cissa".[30] The association of Cissbury with Cissa is a 16th-century antiquarian invention. Records show that Cissbury was known as Sissabury in 1610, Cesars Bury in 1663, Cissibury in 1732 and Sizebury in 1744. A local tradition suggests that the camp was built and named after Cæsar. [31][32] It is thought possible that Cissbury was used in the late Anglo-Saxon period,[10] during the reigns of Ethelred II and Cnut as a mint. Old Iron Age forts were used as mints, during dangerous times, such as when there were frequent Viking raids. However, there has been no archaeological confirmation of Cissbury being occupied by Anglo-Saxons.[31][33]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Kelly. Anglo-Saxon Charters VI. pp. 3–13.

- ^ Welch. Early Anglo Saxon Sussex in Brandon's South Saxons p. 24 – Mercredesburne means "river of the frontier agreed by treaty"

- ^ a b ASC 477, 485, 491 – English translation at project Gutenberg. Retrieved 5 March 2013

- ^ a b c Jones.The End of Roman Britain. p.71. – ..the repetitious entries for invading ships in the Chronicle (three ships of Hengest and Horsa; three ships of Aella; five ships of Cerdic and Cynric; two ships of Port; three ships of Stuf and Wihtgar), drawn from preliterate traditions including bogus eponyms and duplications, might be considered a poetic convention.

- ^ a b c d e Gransden. Historical Writing. pp.36–39

- ^ a b Asser. Alfred the Great. pp. 275 – 281. – Discussion of sources, authors, dates and accuracy

- ^ Morris. Dark Age Dates. p.153 – Morris compares a list of known dates with Gildas and Bede's record, he explains that Gildas's date was about 20 years later than the actual date on a lot of the events. Bede took the Gildas date for his reference.

- ^ Down. (1978) p.341. – After the departure of the Romans from Chichester, the earliest Saxon find, by archaeological excavation, was a small amount of mid-Saxon pottery dated around 8th–9th century.

- ^ a b Welch. Early Anglo-Saxons in Brandon's The South Saxons Chapter 11 – a discussion of the Anglo-Saxons in 5th century Sussex.

- ^ a b c Kipfer. Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology. p. 23. – The Early or Pagan Saxon period was from the early settlements until the general acceptance of Christianity in the mid 7th century. The mid period was from the 7th to 9th century and the late period was until the Norman conquest of 1066.

- ^ D J Freke. (1980) Excavations in the Parish Church of St Thomas the Martyr, Pagham, SAC 118 pp. 245–56 – A late-6th-century or early-7th-century cremation urn was found near the church in Pagham Harbour

- ^ Down. Archaeology in Sussex to AD1500. p.56 – The absence of any early Saxon cemeteries or artefacts in or near Chichester, as far as present knowledge goes, is another piece of negative evidence which may lead in the end to the conclusion that, for whatever reason, a sub-Roman enclave existed in and around the old civitas, possibly as late as the early 7th century.

- ^ Bell. Saxon Sussex in Archaeology in Sussex to AD 1500: p.64. – This has led some writers to suggest that an area centred on Chichester remained in sub-Roman hands, throughout the 5th century and perhaps longer. Equally, however, there is no archaeological evidence from Chichester or its surroundings of a sub-Roman population.

- ^ Dodgson. Place-Names in Sussex in Brandon's. The South Saxons. pp. 54–88. – No placenames of Romano-British origin in the Chichester area.

- ^ Gelling. Landscape of Place-Names p.236. Chithurst is possibly a hybrid of the British Chit and OE hyrst

- ^ Slaughter.(2009) in his reconstruction hypothesis the Rulers of the South Saxons before 825, raises the point of negative evidence in terms of any possible sub-Roman presence and is aware of a dearth of fifth-century archaeology in and around Chichester, although he claims that Birdham, earlier Bridenham, might derive from Britwend + ham. during this period.

- ^ Welch. Early Anglo-Saxons in Brandon's The South Saxons. p. 27 – description of brooch and picture on p.151 (Plate 1.1)

- ^ a b Morris. (1973.)The Age of Arthur p.94 – Morris cross references British sources and Anglo-Saxon Archaeology as well as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to produce his conclusions.

- ^ Bede, Ecclesiastical History, II 5.

- ^ a b Henry, Archdeacon of Huntingdon: Historia Anglorum. Sources section p.lxxxvi. Henry was one of the 'weaver' compilers of whom Bernard Guenée has written. Taking a phrase from here and a phrase from there, connecting an event here with one there, he wove together a continuous narrative which, derivative though it mostly is, is still very much his own creation,...

- ^ Henry, Archdeacon of Huntingdon: Historia Anglorum Chapter. II - Analysis of sources that survive and sources that are now lost.

- ^ a b Henry, Archdeacon of Huntingdon: Historia Anglorum. Lost Sources p.ciii. Greenway suggests that Roger of Wendover took his account from Henry of Huntingdon and Matthew Paris took his from Roger of Wendover. The evidence for this is that Roger sometimes used Henry's words verbatim and sometimes paraphrased them.

- ^ Henry, Archdeacon of Huntingdon: Historia Anglorum. p.91 – And so Duke Ælle with his sons and a fleet that was well equipped with fighting men, landed in Britain at Cymenes ore, When the Saxons disembarked, however, the Britons raised the alarm and a great number rushed from the surrounding districts and immediately gave battle. But the Saxons, who were much taller and stronger, received their disorganized attacks with disdain. For coming in small groups at intervals, they were slaughtered by the Saxons' cohesive force, and as each wave returned in shock, they heard the unexpectedly bad news. So the Britons were driven to the nearest forest, which is called Andresleigh.

- ^ Wendover. Flowers of History, p.19.-..In the same year Duke Ælle, the chief, and his three sons, Cymen, Plenting, and Cissa landed in Britain at a place that was after called from Cymen, Cymenshore, which means Cymen's Port. On their landing, then Britains assembled in great numbers and attacked them, but were driven from the field, and obliged to shelter in a neighbouring wood, called Andreswode.

- ^ a b Welch. Early Anglo-Saxon Sussex in Brandon's South Saxons. pp. 27–28

- ^ a b Henry, Archdeacon of Huntingdon: Historia Anglorum. p.97. Footnote57.No genealogy of the South Saxon royal house survives and none seem to have been available to Henry. The death of Aella and the succession of Cissa are probably deduced from ASC 477 and 491..

- ^ Kirkby-Williams (1976). Review of The Age of Arthur. pp. 454–486.

- ^ Dumville/ Keynes. The Anglo Saxon Chronicle. pp. 58–59. (In the Parker MS the annal number has been changed to 895 in another hand). Referring to a Danish raiding party that on its way homeward: "hamweard wende þe Exanceaster beseten hæfde, þa hergodon hie up on Suðseaxum neah Cisseceastre"-" homeward that had beset Exeter, they went up plundering in Sussex nigh Chichester".

- ^ University of Nottingham KEPN.'Cissa's Roman town'. Chichester was Noviomagus Reg(i)norum, capital of Civitas Reg(i)norum. According to the ASC, in 477, Cisse, son of Aelle, led an invasion of Sussex. There seems to be some confusion over whether personal name was derived from the place-name or vice versa.

- ^ Camden. Britannia. p.312 – But Cisburie the name of the place doth plainely shew and testifie that it was the worke of Cissa: who beeing of the Saxons line the second king of this pety kingdom, after his father Ælle, accompanied with his brother Cimen and no small power of the Saxons, at this shore arrived and landed at Cimenshore, a place so called of the said Cimen, which now hath lost the name; but that it was neere unto Wittering..

- ^ a b Coates. Studies and Observations on Sussex Place-Names in SAC Vol.118 pp. 309–329

- ^ Hudson 1982, p. 231.

- ^ Hill. The Origins of Saxon Towns in Brandon's The South Saxons. pp. 187–189

References

[edit]- Asser (2004). Keynes, S. (ed.). Alfred the Great. Penguin Classics. Translated by Lapidge, M. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044409-4.

- Bede (1991). D.H. Farmer (ed.). Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Translated by Leo Sherley-Price. Revised by R.E. Latham. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044565-X.

- Bell, Martin (1978). "Saxon Sussex". In Drewett, P. L. (ed.). Archaeology in Sussex to AD 1500: essays for Eric Holden. Research Report Series. Council for British Archaeology. ISBN 0-900312-67-X.

- Camden, William (1610). Britannia Vol 1 (English ed.). London: Philemon Holland.

- Coates, Richard (1980). Bedwin, Owen (ed.). "Studies and Observations on Sussex Place-Names". Sussex Archaeological Collections. 118. Lewes, Sussex: Sussex Archaeological Society. doi:10.5284/1086791.

- Dodgson, J. McNeil (1978). "Place-names in Sussex". In Brandon, Peter (ed.). The South Saxons. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 0-85033-240-0.

- Down, Alec (1978). "Roman Sussex: Chichester and the Chilgrove Valley". In Drewett, Peter (ed.). Archaeology in Sussex to AD 1500: essays for Eric Holden. Research Report Series. Council for British Archaeology. ISBN 0-900312-67-X.

- Fouracre, Paul, ed. (2006). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. 1: c. 500 – c. 700. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36291-1.

- Dumville, David; Keynes, Simon (1986). Bately, J.M (ed.). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. 3 MS A. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-103-0.

- Freke, D. J. (1980). Bedwin, Owen (ed.). "Excavations in the Parish Church of St Thomas the Martyr, Pagham". Sussex Archaeological Collections. 118 (118). doi:10.5284/1086750.

- Gransden, Antonia (1974). Historical Writing in England c.550-c1307. London: Routledge and Kegan Paull. ISBN 0-7100-7476-X.

- Gelling, Margaret (2000). The Landscape of Place-Names. Stamford: Tyas. ISBN 1-900289-26-1.

- Hudson, T. P. (1982). "Historical notes: The place-name 'Cissbury'" (PDF). Sussex Archaeological Collections. 120. Lewes, Sussex. doi:10.5284/1000334.

- Henry of Huntingdon (1996). Greenway, Diana E. (ed.). Historia Anglorum: the history of the English. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 0-19-822224-6.

- Hill, D (1978). "The Origins of Saxon towns". In Brandon, Peter (ed.). The South Saxons. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 0-85033-240-0.

- Jones, Michael E. (1988). The End of Roman Britain. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8530-4.

- Kelly, Susan E., ed. (1998). Charters of Selsey. Anglo-Saxon Charters VI. OUP for the British Academy. ISBN 0-19-726175-2.

- Kipfer, Barbara Ann, ed. (2000). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology. New York: Kluwer Academic/ Plenum Publishers. ISBN 0-3064-6158-7.

- Kirby, D. P.; Williams, J. E. C. (1976). "Review of The Age of Arthur, a History of the British Isles from 350 to 650 by John Morris". Studica Celtica (10–11).

- Morris, John (1973). The Age of Arthur. London: Phoenix. ISBN 1-84212-477-3.

- Morris, John (1965). Jarrett; Dobson (eds.). Britain and Rome : Dark Age Dates: essays presented to Eric Birley on his 60th birthday.

- Roger of Wendover (1849). Roger of Wendover's Flowers of History VI. Translated by Giles, J. A. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Slaughter, David (2009). Rulers of the South Saxons before 825. Published by Author.

- Swanton, Michael (1996). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92129-5.

- University of Nottingham. "Key to English Placenames". EPNS. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

External links

[edit]- St Thomas a Becket – Parish Church at the East end of Pagham Harbour Various AS artefacts found in the area including a cremation urn restored and dated by British museum.