Christianization of the Roman Empire as diffusion of innovation

Christianization of the Roman Empire as diffusion of innovation looks at religious change in the Roman Empire's first three centuries through the lens of diffusion of innovations, a sociological theory popularized by Everett Rogers in 1962. Diffusion of innovation is a process of communication that takes place over time, among those within a social system, that explains how, why, and when new ideas (and technology) spread. In this theory, an innovation's success or failure is dependent upon the characteristics of the innovation itself, the adopters, what communication channels are used, time, and the social system in which it all happens.

In the empire's first three centuries, Roman society moved away from its established city based polytheism to adopt the religious innovation of monotheistic Christianity. Instead of explaining this through political and economic events, this approach focuses on the power of human social interactions as the drivers of societal change. This combines an understanding of Christian ideology and the utility of religion with analysis of social networks and their environment. While there are alternative explanations of Christianization of the Roman Empire, with differing levels of support from contemporary scholarship, this approach demonstrates that the cultural and religious change of the early Roman Empire can be understood as the cumulative result of multiple individual behaviors.[1]

Christianity was adopted relatively quickly. Five characteristics of diffusion can explain the speed at which this happened: first, if an innovation is seen as having a relative advantage over what it is replacing, it will be adopted more quickly. Christianity's relative advantage over its various competitors can be found in its altruism, its acceptance of those without Roman status, and the specific type of network it formed. Second, its compatibility with the people, society, or culture it coexists with will impact the rate of adoption. Christianity was not highly compatible with Roman polytheism, but it was compatible with the Judaism found in the diaspora communities. Its complexity also matters, since simple is generally adopted faster, and Christian inclusivity made it relatively simple. The next characteristic, trialability, is about how well the innovation allows access to information about itself before someone becomes a full-fledged member, and the conversion process in early Christianity allowed a flexible period of trialability. The last characteristic affecting speed of adoption is observability, because it is more likely someone will convert if the individual believes they have seen results. This is represented by who it was who adopted it, and by the social changes, such as charity and martyrdom, that those different adopters helped create. These qualities interact and are judged as a whole. For example, an innovation might be extremely complex, reducing its likelihood to be adopted and diffused, but it might also be very highly compatible, giving it a larger advantage relative to current tools, so that in spite of specific problems, potential adopters adopt the innovation anyway.[2]

Sociologist E. A. Judge explains Christianization through this sociological view as having occurred as a result of the powerful combination of new ideas Christianity offered, and the social impact of the church, which he says formed the central pivotal point for the religious conversion of Rome.[3][4]

Network theory and Diffusion of innovation as an approach

[edit]In the early Roman Empire, Christianity began with fewer than 1000 people. It grew rapidly, despite intense and continuing competition from both traditional polytheism and alternative cults and creeds.[5] It included approximately 200,000 people by the end of the second century, substantially accelerating its growth in the third century, achieving a bare majority by 350.[6][7][8] These religious changes have become a much studied example of how networks function in the real world.[9]

When small groups connect to others based on shared information, archaeologist Anna Collar says networks form.[10][11] These networks are depicted by points, called nodes, with each node representing an individual small group, interconnected by lines called edges. The edges represent the channels of communication between them.[12]

The emphasis is on human interactions as the drivers of change. People tend to form small groups, along social lines, with those they share something in common.[13] Societal change can then be seen as a kind of emergence – the collective behavior that results from individuals as parts of a system doing together what they would not do alone – as Christianity was 'self-organized', distributed away from any central authority, and was based on common causes.[14]

When groups of people with different ways of life come into contact with each other, interact, and exchange ideas and practices, "cultural diffusion" takes place.[15] Diffusion is the social process that spreads the new ideas and practices.[16] It is the primary method by which societies change; (it is distinct from colonization which forces elements of a foreign culture into a society).[17]

Diffusion can only occur within a social system, therefore that system's established social structure affects the innovation's diffusion. Instead of judging an innovation on its qualities, diffusion of innovation views success as an indication of the connectivity of the network structure in which it happens to be situated: whether that society is ‘vulnerable’ or ‘stable’ with regard to that particular innovation.[18] Christianity's success can be viewed as an indication of the connectivity of Roman society and its vulnerability to innovation.[18]

Innovation

[edit]Diffusion of innovation is a special kind of communication which focuses on new ideas. The newness of the idea is what gives it its special character.[19] An innovation is an idea, practice or object which is perceived as new by the person considering adopting it. It doesn't matter if it is or isn't objectively new; it only matters if it is seen as new by the individual contemplating adoption.[20] A true religious innovation must involve a significant change – such as the shift from polytheism to monotheism – on a large scale.[21] Archaeologist Anna Collar argues that even though "the philosophical argument for one god was well known amongst the intellectual elite, ... monotheism can be called a religious innovation within the milieu of Imperial polytheism."[22]

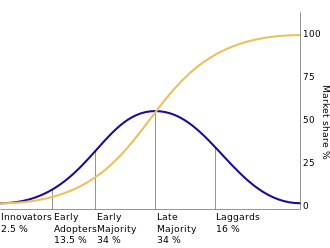

The adoption of innovation occurs in stages.[18][23] These stages are represented by the different types of people who adopted it, and whether they did so early or late, thus indicating that people have differing degrees of susceptibility to innovations.[18][24] In its first three centuries, Christianity evidences innovators, early adopters, and the early majority.[18] (Two later categories of the fourth to seventh centuries are called the late majority and laggards).[25]

The rate of the individual's decision making process is, therefore, a factor in the innovation's success.[25][26] The variance between people's responses creates a normal distribution curve. Collar explains, "there is a point on the curve that represents the crux of the diffusion process: the ‘tipping point’.[18] This 'tipping' takes place between 10 percent adoption and 20 percent adoption.[27] American sociologist Everett Rogers says, "After that point, it is often impossible to stop the further diffusion of a new idea, even if one wished to do so".[28][18] Christianity achieved this tipping point, (called critical mass) in the hundred years between 150 and 250 when it moved from less than 50,000 adherents to over a million.[29] Scholars generally agree there was a significant rise in the absolute number of Christians in the rest of the third century.[8] This provided enough adopters for it to be self-sustaining and create further growth, thereby establishing Christianity as a successful innovation in the Roman empire.[29][30][31]

Alternative approaches

[edit]Edward Gibbon wrote the first historiographical view of how the Roman Empire was Christianized in his The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire published in 1776. Gibbon attributed it to Constantine whom he saw as driven by "boundless ambition" and a desire for personal glory to impose Christianity on the rest of the empire – from the top down – in a cynical, political move.[32][33] Gibbon believed this was how Constantine's religion "achieved, in less than a century, the final conquest of the Roman empire".[34][35][36] Classics professor Seth Schwartz asserts that the number of Christians at the end of the third century indicate Christianity's success predated Constantine.[37] Social scientist Edwin A. Judge has written a detailed study showing a fully organized church system existed before Constantine and the Council of Nicaea. From this, Judge writes that "the argument Christianity owed its triumph to its adoption by Constantine cannot be sustained".[38] Currently, there is agreement among scholars that Christianization did not happen by ‘‘top-down’’ imposition in the centuries preceding Constantine. Instead, it happened through its acquisition by one person from another, through imitation, and through learning what constituted Christian self-identification.[39]

Contemporaries like Pliny the Younger employed the model of the spread of disease to describe the spread of Christianity in Pontus in northern Asia Minor: "it was not only in towns, but also in villages and the countryside that the contagion of this dreadful superstition has spread".[40] Price writes that ‘contagious disease’ is a misleading metaphor. It embodies a negative view, and it leads to the idea of a linear spread where the new cult infected each place it passed through, and this was not the case in Roman Empire.[40] Collar says the spread of innovation differs from the spread of disease because innovation requires active adoption by the individual concerned; this differs considerably from their vulnerability to infectious disease.[41][40]

Psychological explanations of Christianization have largely been based on the belief that paganism declined during the imperial period creating an era of insecurity and anxiety.[42][43][44] Historians thought this produced anxious alienated individuals who sought refuge in religious communities which offered socialization.[45] For classics scholar James B. Rives, "the notion that traditional public cults and traditional Graeco-Roman deities were in any sort of decline during the Hellenistic and imperial periods depended on a set of highly dubious assumptions,[46] and could be confirmed only by a very selective and even arbitrary use of evidence. It can now no longer be maintained".[47] Traditional religion did not decline but remained vibrantly alive into the sixth and seventh centuries.[47][48] Psychologist Pascal Boyer says a cognitive approach can account for the transmission of religious ideas and describe the processes whereby individuals acquire and transmit certain ideas and practices, but the cognitive theory may not be sufficient to account for the social dynamics of religious movements, or the historical development of religious doctrines, which are not directly within its scope.[49]

A Neo-Darwinian theory of cultural selection indicates behaviors spread because people have a strong tendency to imitate their neighbors when they believe those neighbors are more successful.[50] Anthropologists Robert Boyd and Peter J. Richerson write that Romans believed the early Christian community offered a better quality of life than the ordinary life available to most in the Roman Empire.[51] Care-taking was particularly important during the severe epidemics of the Imperial period when some cities devolved into anarchy.[52] Pagan society had weak traditions of mutual aid, whereas the Christian community had norms that created “a miniature welfare state in an empire which for the most part lacked social services”.[51] In Christian communities, care of the sick reduced mortality by, possibly, as much as two-thirds. Extant Christian and pagan sources indicate many conversions were the result of "the appeal of such aid".[51] According to Garry Runciman, a distinctly Christian phenotype of strong reciprocity and unconditional benevolence evolved thereby producing the growth of Christianity.[50]

Failure of diffusion

[edit]Not all innovations succeed.[53] Sociologist Gabriel Tarde is quoted as saying: "given one hundred different innovations conceived at the same time ... ten will spread abroad while ninety will be forgotten".[54] In the Roman imperial period, there were many appealing new cults and religions along with variants of Christianity such as Gnosticism, Manichaeism and Donatism.[55] All of these religious innovations were successful for a time, yet eventually failed. A belief system's intrinsic qualities can explain its attractiveness but they are insufficient to explain the failure of other ideas that were also highly attractive.[56]

Innovations can fail if pre-existing beliefs within the social system are strong enough they obstruct adoption.[57] Innovations can fail because the message is not suited to the "client's" needs.[11] They can fail because of how the change agent is seen by potential converts,[11] or from competition from other innovations,[58] or from the perceived attributes of the innovation itself.[59] Even simple inertia can prevent adoption.[60] When an innovation becomes too closed a system, it will often fail,[61] or when there is a lack of commonality with its social system an innovation will also often fail.[62] Failure can also be influenced by very personal reasons for why individuals adopt, or don't adopt, an innovation, but this is a less researched area, because it is difficult to study says Rogers, and because it is affected by the broader context.[63]

Five characteristics of diffusion

[edit]Relative advantage

[edit]

The greater the perceived advantage the innovation has over what it is replacing, the more the rate of adoption will increase. [64] W. G. Runciman writes: "If there was a single characteristic of the Christian religion which distinguished it from all its competitors, Judaism included, it was the willingness, at least in principle, of Christians not only to accept converts from wherever they came [such as slaves and women] but to display, or at least be prepared to display, towards the unconverted the same kind of active benevolence [alms giving] that they were expected to display towards one another".[39] Recent research has shown it was the formal unconditional altruism of early Christianity that accounts for much of its otherwise surprising degree of success.[31] According to Boyd and Richardson, this created a kind of welfare state within an empire which for the most part had no such thing, and this gave Romans the belief that the early Christian community offered a better quality of life.[51]

Alms

[edit]Life in the Roman Empire differed markedly based on whether one was wealthy, "humble" or genuinely poor. Schemes that might appear to be aimed at helping the poor, (Trajan's alimentary scheme or the grain dole (annona) at Rome) were distributed based on 'worth' rather than need.[65] The wealthy supported their own who had fallen on hard times, first and foremost, and philanthropy was likely to be a display of personal wealth rather than concern for the needy.[66] Prior to Christianity, the wealthy elite of Rome mostly donated to civic programs designed to elevate their social status, though personal acts of kindness to the poor were not unheard of.[67][68][69]

Early Christianity demanded a high standard of personal virtue and 'righteousness' in order to enter the kingdom of God, and almsgiving was considered the premier virtue.[70] In his Homilies on St.John, John Chrysostom writes that "It is impossible, though we perform ten thousand other good deeds, to enter the portals of the kingdom without almsgiving".[70] For Chrysostom, this was a statement of "continued redemption" first offered by "the historical Jesus on the cross, and now in the present through the poor. To approach the poor with mercy was to receive mercy from Christ".[71] Almsgiving was regarded as an act of love which was itself regarded as redemptive.[72] Religion scholar Steven C. Muir adds that "Charity was, in effect, an institutionalized policy of Christianity from its beginning. ... While this situation was not the sole reason for the group's growth, it was a significant factor".[73]

Slavery through the fifth century

[edit]According to early Christian historian Chris L. de Wet, slavery suffered a complete systemic collapse in the fifth century due to the lack of supply and demand.[74] Causes of this are not fully understood as precise numbers of slaves have not been established for comparison's sake. It is established that Christianity of this period never openly called for the abolition of slavery.[75] However, there is evidence indicating Christian discourse against slavery was oft repeated and shaped late ancient feelings, tastes, and opinions concerning it.[76] Helmut Koester asserts that "the Christian community in the letters of Paul, begins with a baptismal formula, which says in Christ there is ... neither slave nor free. This is a sociological formula that defines a new community ... [giving] even the lowliest slave personal dignity and status".[77][78]

From the beginning, the Pauline communities cut across the social ranks in a conscious dismantling of traditional Roman concepts of hierarchy and power.[79][80] Meeks, asserts that evidence from Pliny the Younger demonstrates this.[81] Paul's understanding of the paradox of a powerful Christ who died as a powerless human led to the creation of a new order unprecedented in classical society.[82] Classicist Kyle Harper describes the impact of Christianity as "a revolution in the rules of behavior, but also in the very image of the human being".[83]

In Paul's Epistle to Philemon, the slave Onesimus had run away – a capital offense – to join Paul. But both Onesimus and his master Philemon had become Christians. Paul sent Onesimus back home with a letter in which Paul insists on Philemon's acceptance of Onesimus as a 'beloved brother'.[84][85] New Testament professor Marianne Thompson has argued convincingly that "a reading of the letter to Philemon which views Paul as asking for Onesimus' spiritual reception as a brother in Christ, without the setting free of his body as a slave, assumes a 'dualistic anthropology' in Paul which his writings do not confirm".[86] The cumulative weight of Paul's many suggestive phrases support this view.[87] If the information in Colossians 4:7–9 is historical, the slave Onesimus became a freedman.[88] Professor of Classics and Letters Kyle Harper argues that religious feeling favoring manumission runs throughout the eastern provinces.[89]

Christianity adopted slavery as one of its main metaphors in its assertion that all humans are slaves to sin.[90][91] There are no extant sources written by slaves,[92] but Christian rhetoric is filled with that metaphorical perspective. John Chrysostom's surviving corpus alone mentions slavery over 5,000 times.[93] Chrysostom wrote baptismal instructions for churches in his jurisdiction, telling the officiating priest to stop at various points to remind the catechumens of how the act of baptism frees them by making them holy and just sons of God as joint-heirs with Christ. "Repeated so often, in such an important context, this message must have made a major impact on the thinking of Christian congregations and those with whom they interacted".[94]

The most prolific source of slaves was natural reproduction (childbearing), since a child born to a slave was automatically a slave, without option, themselves. De Wet writes that Christian leaders such as John Chrysostom attempted to "guard the sexual integrity of the slave by desexualizing the slave's body and criminalizing its violation. Slaves were no longer morally neutral ground – having sex with a slave while married was adultery and if unmarried, fornication".[95] These teachings, along with the proliferation of chastity among slaves who became Christian,[96] and the spread of asceticism through Roman society as a respected value, may have lessened their sexual use and their reproductive value and impacted slavery directly.[76][97]

Chrysostom reflects Paul's dual teaching on slavery. He supported the obedience of slaves to their masters. He also told his church' audience, which consisted mostly of wealthy slave holders, that "Slavery is the result of greed, of degradation, of brutality, since Noah, we know, had no slave, nor Abel, nor Seth, nor those who came after them. The institution was the fruit of sin".[98] MacMullen has written that slavery was "rebuked by Ambrose, Zeno of Verona, Gaudentius of Brescia, and Maximus of Turin", among others.[99]

Runciman shows that strong reciprocity between Christians, combined with this kind of unconditional benevolence toward others, "made Christianity into a movement which, by the second half of the third century, the Roman state could neither ignore nor suppress".[100]

Geography and a scale free network

[edit]

The spread of Christianity began from Jerusalem.

In their study on spatial constraints on diffusion, Fousek et al show that "The spread of Christianity in the first two centuries follows a gravity-guided diffusion".[101] Gravity models are used to study flow: this application estimates the flow of interaction between any given two cities. Fousek shows that interaction between cities increases with higher populations and decreases with distance and higher costs of travel.[101]

The gravity model shows that the shortest path for the spread of any innovation is its most probable path. This modular pattern shows the direct influence of Jerusalem on founding churches that were geographically close.[101] These were small home churches such as that in Caesarea Maritima of around 12–200 members each.[102] Prior to the year 100, Christianity was composed of, maybe, one hundred of them.[103]

The Empire itself provided Christianity's ability to move beyond the local geographic area through the advantage of Roman roads and the links between Roman cities.[17][104] Having begun moving outward from Jerusalem, Christianity also directly connected to remote large cities such as Rome. All the largest cities in the empire had Christian congregations by the end of the first century.[105]

The first two centuries then show clusters of smaller Christianized cities in the neighborhood of these large regional centers. Some communities had few connections to other communities, and others had more. Communities with multiple connections served as "hubs" around which others clustered. Hubs are important to the transfer of information.[106] As this kind of network develops, there is a high probability that, as more and more communities join an already existing system, they will link themselves to the community which already has many links.[107] This clustering is characteristic of the modular scale free network that Christianity formed.[107][108]

In the case of early Christianity, as the new cities became hubs – they became new points of origin for spreading the innovation – and Christianization no longer relied on its first point of origin for information. This is in agreement with the knowledge that, from a very early phase, cities such as Antioch and Alexandria became more influential than Jerusalem.[105][108][39] Within a large social network such as the early Christian church, high local clustering of small groups that were not far apart, promoted a "small-world effect". Being part of a small-world promotes information flow at the local level, thereby making the larger network tightly connected.[109]

Compatibility and complexity

[edit]Compatibility is the degree to which an innovation is seen as consistent with existing values, past experiences and the needs of potential adopters. [110] It is possible for an incompatible innovation to be adopted, but it often requires the adoption of a new value system which slows the process.[111] Christianity had some compatibility with Roman culture in its moral language which was adapted from older traditions.[112] For example, in the biblical book of Acts, the author alludes to the defense of Socrates: "One must obey God rather than men".[113] In general, however, Christianity faced great problems representing itself to the empire in relation to most issues of polytheistic religious tradition. In the eyes of many non-believers, it was an unacceptable form of superstitio; its founder had been executed by Roman authority, it was seen as having fallen away from the faith of the Jews, and could, therefore, claim no legitimate authority.[114] [note 1]

What made Christianity incompatible with much of paganism did not make it incompatible with Judaism.[122] During the imperial period, many Jews left Palestine for places like Alexandria, Rome, North Africa and the Mediterranean region, due to persecution, politics, and expulsion, because of internal conflicts in Jewish society, and for economic opportunities outside Palestine. These were the dispersed peoples: the Diaspora.[123] Syrian church historian Bar Hebraeus puts the total number of Jews throughout the entire Roman empire, at the time of the emperor Claudius, at 6,944,000. There were about a million Jews in Egypt, and less than two million Jews in Judea. That indicates there were more Jews - about four million - spread throughout the Diaspora than there were within Judea itself in the first century.[124] Innovations are fundamentally linked to their cultural environment.[18] Paula Fredriksen has written that, within the Jewish Diaspora, there was an international population that "resonated with the religious ideas [of Christianity] ... it's because of that, because of Diaspora Judaism, which is extremely well established, that Christianity itself, as a new and constantly improvising form of Judaism, is able to spread as it does throughout the Roman world".[125]

Complexity is concerned with how difficult an innovation is to grasp and use, since simpler tends to be adopted more rapidly.[111] Christianity was unhindered by either ethnic or geographical ties. It was experienced as a new start, and was open to both men and women, rich and poor. Baptism was free. There were no fees, and it was intellectually egalitarian, making philosophy and ethics available to ordinary people including those who might have lacked literacy.[126]

Trialability

[edit]Conversion is an information seeking – information processing activity.[127] An individual wants to know the advantages and disadvantages of adopting or rejecting an innovation before fully committing.[128] Rogers conceptualizes five sequential steps in this process: knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation and confirmation. The conversion process begins when an individual becomes aware of the innovation and gains some knowledge of how it functions. Persuasion follows when that individual forms a favorable attitude toward the innovation. The decision period begins when the individual engages in activities that will lead to adoption or rejection. Implementation puts the innovation to use and may involve re-invention.[127] Confirmation seeks reinforcement.[127]

In the empire, this involved becoming part of an established community of adopters who would "instruct, admonish, cajole, remind, rebuke, reform, and argue" for the change, says Meeks.[129] E. R. Dodds writes that Christianity offered a fuller sense of community "than any corresponding group of Isis followers or Mithras devotees".[130] In Christianity's earliest communities, candidates for baptism were introduced by a teacher or other person willing to stand surety for their character and conduct.[131] These catechumen were thereafter instructed in the major tenets of the faith, examined for moral living, sat separately in worship, could not receive the eucharist (the common unifier for Christian communities), and were generally expected to demonstrate commitment to the community and obedience to Christ's commands before being accepted and baptized into the community as a full member. This "trial period" for those called catechumens could take anywhere from months to years.[132]

Reinvention

[edit]An innovation is not necessarily static and unchanging during the diffusion process. A user may adapt and change the innovation in order to fit their personal situation and needs more closely.[133] This occurs most frequently at the implementation stage of adoption.[127] The degree to which the variation departs from the mainline version first presented to them, is a re-invention, and it can occur frequently in a variety of ways.[134] Such re-inventions can begin to diffuse separately from the original innovation.[135] Whether this is "good" or "bad" depends upon point-of-view. Reinvention can make an individual's continuance in the innovation more likely, while in some extreme cases, the original innovation can completely lose its identity.[136] This can produce "anti-diffusion programs designed to prevent the diffusion of "bad" innovations".[137] (See: Gnosticism, Donatism, and Manichaeism.) Rejection, discontinuance and re-invention frequently occur during the diffusion process.[138]

Observability

[edit]Rogers explains "Observability is the degree to which the results of an innovation are visible to others. The easier it is for individuals to see the results of an innovation, the more likely they are to adopt it".[111] Therefore, as Collar points out, the success or failure of any religious innovation depends upon the social environment it helps create.[139]

Innovators of the first century

[edit]In the diffusion model, those who first recognize and adopt a new idea are called innovators. They are of prime importance.[140] They are often on the fringes of society, and launch the innovation, (in this case Christianity), into the social system from outside the system.[141][142] In the first century, Jews were outsiders to the established Roman religious system, and it was approximately 700 converted Jews, including Paul and the other Apostles, who first introduced Christianity to the Roman Empire.[143][144]

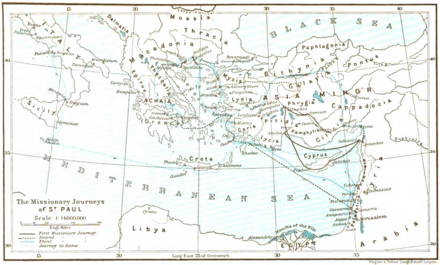

Collar argues that Paul the Apostle was one of Christianity's original innovators.[145] He converted to Christianity sometime within a few years of Jesus' death on the "Road to Damascus" as recorded in Acts 9:13–16 and Galatians 1:11–24. Paul made three (possibly four) missionary journeys, but there is no scholarly agreement on exactly when Paul was converted and when these journeys began. John Knox dated Paul's conversion to AD 34–35 at the earliest.[146] Between 45 and 49, Paul founded the church in Antioch, where the term Christian was first used to refer to both Jews and Gentiles of the new faith (Acts 11:26). Paul founded churches in four Roman provinces: Galatia, Macedonia, Achaia and Asia. In Asia alone, he founded churches in the towns of Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamon, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, Laodicea on the Lycus, Colossae, and Hieropolis. He founded churches in Roman Syria (Acts 15:40–41) and Crete, and possibly Illyricum (Romans 15:19), Arabia Petraea and Hispania.[147]

All 12 Apostles are alleged to have made missionary journeys and founded churches in the first century.[148] In the year 47, the Church of the East was founded in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) by Thomas the Apostle.[149] Indian historian K. S. Mathew writes that it has been proven "indubitably" that after Thomas left Mesopotamia, he began to preach the gospel in India in the year 52.[150][151] Thomas's alleged visit to China is mentioned in the Indian books and church traditions, such as the Malayalam ballad Thomas Ramban Pattu (The Song of the Lord Thomas), of the Saint Thomas Christians.[152] Saint Thomas Christians claim descent from the early Christians evangelized by Thomas the Apostle in AD 52. Sources indicate Thomas came to India, went to China, and came back to India where he died.[152]

Paul's journeys ended with his death, probably in Rome, under Nero before the end of Nero's reign in 68. The beheading of Paul (1 Clem 5:5–7), and Peter being crucified upside-down are recorded in Tertullian's Prescription Against Heretics chapter XXXVI, and also in Eusebius' Church History Book III chapter I.[153]

Early adopters in the first and second centuries

[edit]"Innovators must be connected to early adopters ... if the innovation is to spread beyond the initial group".[140][154] Unlike the innovators, early adopters are usually a respected part of their local social system and are therefore able to tip the scale in favor of the innovation they adopt.[141] According to social anthropologist and Biblical scholar Wayne A. Meeks, the absence of source material means it is not possible to write an empirical sociology of early Christianity.[155] However, the Pauline epistles provide some of the earliest documentary evidence showing women, connected to Paul, among the early adopters of the religious innovation in the Roman Empire.[156] Women of note, who were a respected part of their local social system, were attracted to Christianity as evidenced in the Acts of the Apostles where mention is made of Lydia of Thyatira, the seller of Tyrian purple at Philippi, and of other noble women at Thessalonica, Beroea and Athens (Acts 17:4, 12, 33–34).[157][29][30] There is insufficient evidence to say exactly how many women of the first century empire owned property or engaged in trade, but there is evidence that some did.[158]

The New Testament names women as leaders who contributed directly to the spread of the early movement with their roles comparable to those of men.[159][160] Sarah B. Pomeroy says "never did Roman society encourage women to engage in the same activities as men of the same social class."[161] Art historian Janet Tulloch has observed that "Unlike the early Christian literary tradition, in which women are largely invisible, misrepresented, or omitted entirely, female figures in early Christian art play significant roles in the transmission of the faith".[162] There are a number of signs that women did enjoy a functional equality in Christianity that would have been unusual in the larger Roman society and "quite astonishing" in Second Temple Judaism.[163]

There is also some evidence of a similar disruption of traditional women's roles in some of the mystery cults, such as Cybele, but there is no evidence this went beyond the internal practices of the religion itself. The mysteries created no alternative to the patterns in larger society.[164] There is no evidence of any effort in Second Temple Judaism to harmonize the roles or standing of women with that of men.[165] Roman empire was an age of awareness of the differences between male and female. Social roles were not taken for granted. They were debated, and this was often done with some misogyny.[166] Paul uses a basic formula of reunification of opposites, (Galatians 3:28; 1 Corinthians 12:13; Colossians 3:11) to simply wipe away such social distinctions. In speaking of slave/free, male/female, Greek/Jew, circumcised/uncircumcised, and so on, he states that "all" are "one in Christ" or that "Christ is all". This became part of the kerygma of the early church.[166]

These early women took risks to spread the gospel.[167] This is evident in the sanctions and labels found in pagan writings such as The True Word by Celsus, a treatise against Christianity and the women he held responsible for it.[168] Power resided with the male authority figure, and he had the right to label any uncooperative female in his household as insane or possessed, to exile her from her home, and condemn her to prostitution.[169] Professor of religious studies Ross Kraemer theorizes that "Against such vehement opposition, the language of the ascetic forms of Christianity must have provided a strong set of validating mechanisms", attracting large numbers of women.[170][171]

In church rolls from the second century, there is conclusive evidence of groups of women with some "exercising the office of widow".[172] Roman historian Geoffrey Nathan explains that "a widow in Roman society who had lost her husband, and did not have money of her own, was at the very bottom of the social ladder".[173] The early church provided practical support to those who would, otherwise, have been in destitute circumstances. Esther Yue Lhis Ng writes that this "was in all likelihood an important factor in winning new female members".[172][174]

Third century early majority

[edit]While each group is important in the process of diffusion, it is the group called the "early majority" that are critically important to long term success or failure.[55] By adopting it, these are the people who legitimize it for the rest of society.[175] They take the ideas and practices created by the small pockets of innovators and early adopters and turn those ideas and practices into knowledge that is trusted. Their unique position between the very early and the relatively late makes them an important link in the diffusion process. They provide interconnectedness in the system's network.[176]

Christianity's growth was substantially accelerated in the third century. Between 193 and 235, the empire was ruled by the Severan dynasty. There was a large influx of the upper classes into the church during this period. [26][15][177] Christian monasticism emerged, and the numbers of monks grew such that, "by the fifth century, monasticism had become a dominant force impacting all areas of society".[178][179]

Two devastating epidemics, the Antonine Plague in 154 and the Plague of Cyprian in 251, killed large numbers of the empire's population.[180] Graeco-Roman doctors tended largely to the elite, while the poor mostly had recourse to "miracles and magic" at religious temples.[181] Christians tended to the sick and dying, as well as the aged, orphaned, exiled and widowed.[182][183] The monastic health care system was innovative in its methods.[184] By the fifth century, the founding of hospitals for the poor had become common for Bishops, Abbots and Abbesses.[185] Helmut Koester says that Christianity's success was connected to the establishment of these institutions.[186]

Sexual morality

[edit]Classical scholar Kyle Harper writes that Christianity in the third and fourth centuries drove profound social and cultural change, and this is demonstrated in the creation of a new relationship between sexual morality and society.[187] Both the ancient Greeks and the Romans cared and wrote about sexual morality within categories of good and bad, pure and defiled, and ideal and transgression.[188] These ethical structures were built on the Roman understanding of social status. Slaves were not thought to have an interior ethical life because they had no status; they could go no lower socially. They were commonly used sexually, while the free and well-born who used them were thought to embody social honor and the ability to exhibit the fine sense of shame and sexual modesty suited to their station.[189]

The Greeks and Romans believed humanity's deepest moralities depended upon social position which was given by fate. Christianity advocated the "radical notion of individual freedom centered around ... complete sexual agency".[190] Paul the Apostle and his followers taught that the ethical obligation for sexual self-control was to God, and it was placed on each individual, male and female, slave and free, equally, in all communities, regardless of status. Harper says it was "a revolution in the rules of behavior, but also in the very image of the human being".[83] Christianity impacted the ancient system, where social and political status, power, and the transmission of social inequality to the next generation scripted the terms of sexual morality, with varying degrees of change.[191]

Persecution

[edit]Modular scale free networks such as the early Christian churches, are "robust," which means "they grow without central direction, but also survive most attempts to wipe them out."[108]

Conversion is tied to the direct and intimate interpersonal contacts of that person's social network which is, inevitably, characterized by an individual's loyalties.[192] In Rome, citizens were expected to demonstrate their loyalty to Rome by participating in the rites of the state religion's numerous feast days, processions and offerings throughout the year.[193][194] This often clashed with the new Christian's other loyalties.[195]

- In 202, Roman Emperor Septimius Severus issued a rescript forbidding conversion to Christianity. This was the second imperial rescript, following Emperor Trajan's, against Christianity.[196]

- In 250, an empire-wide persecution took place through an edict by the emperor Decius. This edict was in force for eighteen months, and W.H.C. Frend estimates that 3,000–3,500 Christians were killed, while others apostatised to escape execution.[197]

- In 258, Roman emperor Valerian issued an edict to execute Christian Bishops, Presbyters, and Deacons, including Pope Sixtus II, Antipope Novatian, and Cyprian of Carthage.[198][199] Schor writes that "Persecutions (like Valerian’s) might have thinned the Christian leadership without damaging the network’s long-term growth capacity."[108]

Persecution and suffering were seen by many at the time of these events, as well as by later generations of believers, as legitimizing the standing of the individual believers that died as well as legitimizing the ideology and authority of the church itself.[200] The result of persecution, according to second century Justin Martyr, was that: "... the more such things happen, the more do others and in larger numbers become faithful, and worshippers of God through the name of Jesus".[201] Keith Hopkins concludes that "it was in [the third century] that, in spite of temporary losses, Christianity grew fastest in absolute terms. In other words, in terms of number, persecution was good for Christianity".[202]

Constantine as opinion leader

[edit]

According to Nora Berend, rulers tend to be opinion leaders, and they have often played a significant role in Christianization throughout history.[203] Innovators introduce the innovation, early adopters make it socially acceptable, the early majority legitimizes it, whereas opinion leaders confirm it by adopting it.[204] Empirical findings show that opinion leaders tend to have a central network position. They are members of the social network they influence and have followers.[205] From their position at the center, they can exert a significant amount of social influence affecting the opinions of other connected individuals. Opinion leaders have personal knowledge about the innovation and tend to be less susceptible to established norms and more innovative personally. Opinion leaders increase the speed of the spread of the information stream, the adoption process itself, and increase the maximum adoption percentage. They have critical importance in the diffusion of innovation by word of mouth, and tend to be masters at public relations efforts.[206][207]

Peter Leithart has written that Constantine's life was a dramatic life full of "firsts and foundings": "his questionable origins, conceived, so one legend has it, in a one night stand; his nighttime escape from Nicomedia across Europe to Bologne to reach his father; the vision of the cross that preceded his victory at Rome; his entry into the Council of Nicaea; the death of the heretic Arius in a Greek water closet in Alexandria; disguised bishop Athanasius confronting the emperor as he rode into Constantinople; Constantine's baptism and death and his burial as the "thirteenth Apostle" in the Church of the Apostles ... [he was] the first overtly Christian Roman emperor, the first emperor to support the church, the first emperor to call and participate in a church council, the founder of Constantinople and thereby the founder of the Byzantine Empire, which lasted for the next millennium".[208] Scholars also generally agree that Constantine was highly skilled at politics and managing his own personal image, lying frequently in order to do so, and was fully aware of the influence and power that image gained him.[209]

Constantine's main approach to religion was to use enticement by making the adoption of Christianity beneficial.[210][note 2] According to historian Pat Southern, "Imperial patronage, legal rights to hold property, and financial assistance", granted to the church by Constantine and his descendants, were important contributions to the church's success over the next hundred years.[219] Laws that favored Christianity increased the church's status and made it attractive to Constantine's peers – the aristocratic class – which was important for them to be willing to accept it.[220][221] (The "Late majority" are skeptics who tend to accept innovation only after its acceptance by the average members of a society.[222]) Constantine had tremendous personal popularity and support even amongst the pagan aristocrats. That prompted some individuals to become informed about their emperor's religion.[223] This passed along through aristocratic kinship and friendship networks and patronage ties.[224] Stark explains that conversion moves along social networks formed by personal attachments, but Salzman asserts that class ties were even more important to this group.[225][226] Evidence indicates half the empire had converted to Christianity by 350, while the majority of the elite didn't convert until the 360s and after.[226]

Christianity also adapted by adopting.[227] After Constantine, the border between pagan and Christian had begun to blur. Robert Austin Markus explains that, in society before the fourth century, churchmen like Tertullian saw the social order as irredeemably 'pagan' and "hence to be shunned".[228] But the Edict of Milan (313) had redefined the imperial ideology as one of mutual religious tolerance. What counted as pagan had to be rethought.[229] This produced a "vigorous flowering of a public culture that Christians and non-Christians alike could share" – without the practice of sacrifice – which meant the two religious traditions co-existed, and, for the most part, tolerated each other throughout the period.[230][231][232] By the late fourth and early fifth centuries, polytheism had evolved and adapted many aspects of the new religion, while the structure and ideals of both the Church and the Empire had also been transformed.[233][234]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In response, some presented Christianity as a new kind of ethnic religion in hopes of making it socially acceptable. This was done by second-century apologists who took the approach of referring to Christians as another genos or race, with their own history, and legitimate religious practices.

- This 'third race' concept may have originated in accusations from outsiders such as Suetonius, (Nero 16.2.), who described Christians in a derogatory manner as ‘a genus of people' who held a 'new and mischievous superstitio’. In the Epistle to Diognetus, an extant late second century letter to a Roman official, the anonymous author observes that early Christians functioned as if they were a separate "third race": a nation within a nation.[115]

- The Christian apologist Tertullian in his ad nationes (1.8; cf. 1.20), mocked the accusation that ‘we are called a third race’, yet he is also ambivalent, taking some pride in the uniqueness it represents.[116] The early Christian had exacting moral standards that included avoiding contact with those that still lay in bondage to 'the Evil One' (2 Corinthians 6:1-18; 1 John 2: 15-18; Revelation 18: 4; II Clement 6; Epistle of Barnabas, 1920).[117]

- Believing was the crucial and defining characteristic that set a "high boundary" that strongly excluded the "unbeliever".[118] Keith Hopkins asserts: "It is this exclusivism, idealized or practiced, which marks Christianity off from most other religious groups in the ancient world".[119]

- Aristides, the author of an Apology for Christianity, and others sought to spin the accusation to their advantage, in the hope of obtaining socio-political legitimacy.[120] In Daniel Praet's view, the exclusivity of Christian monotheism formed an important part of its success, enabling it to maintain its independence in a society that syncretized religion.[121]

- ^ * Since 1930, most modern scholars have agreed evidence indicates Constantine's conversion was genuine.[211][208] His concept of Christianity was not the narrow view of the Nicene Christianity that followed him; it was a belief in a broader Christianity as a "big tent" capable of containing different wings.[211] Leithart writes that Constantine "did not punish pagans for being pagans, or Jews for being Jews", and scholars currently agree he was not in favor of suppression of paganism by force.[212][213][214] Constantine's personal views undoubtedly favored one religion over the other, but his imperial religious policy was aimed at including the Church in a broader policy of civic unity which required tolerance of the pagan majority.[215] Constantine never engaged in a purge,[216] there were no pagan martyrs during his reign,[217][218] and pagans remained in important positions at his court.[212]

References

[edit]- ^ Collar 2007, p. 149.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. [page needed].

- ^ Judge 2010, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Hopkins 1998, p. 224.

- ^ Runciman 2004, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Welch & Pulham 2000, p. 197–198.

- ^ Stark 1996, pp. 29, 32, 197.

- ^ a b Runciman 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Collar 2013, pp. 1, 5–7, 34–36, chapter 2.

- ^ Collar 2013, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Rogers 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Collar 2013, p. 8.

- ^ Stark 1995, pp. 153, 230.

- ^ Collar 2013, pp. 6, 36, 39.

- ^ a b Fousek 2018, p. abstract.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 6; 34.

- ^ a b Schor 2009, pp. 493–494.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Collar 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 6.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 11.

- ^ Williams, Cox & Jaffee 1992, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Collar 2007, p. 156.

- ^ Rogers 2003, pp. 10, 188–191.

- ^ Rogers 2003, pp. 37, 254.

- ^ a b Rogers 2003, pp. 20, 29.

- ^ a b Hopkins 1998, pp. 222.

- ^ Collar 2013, p. 325.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 259.

- ^ a b c HARNETT 2017, pp. 200, 217.

- ^ a b Hopkins 1998, p. 193.

- ^ a b Runciman 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Jordan 1969, p. 83, 93–94.

- ^ Gibbon 1906, pp. 279, 312.

- ^ Jordan 1969, p. 94.

- ^ Scourfield 2007, p. 1.

- ^ Brown 1998, p. 650.

- ^ Schwartz 2005, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Harris 2005, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c Runciman 2004, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Price 2012, p. 9.

- ^ Collar 2022, p. 6.

- ^ Russell 1996, p. 72.

- ^ Russell 1996, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Rives 2010, p. 247.

- ^ Russell 1996, p. 100.

- ^ Rives 2010, pp. 242, 247, 249, 250–251.

- ^ a b Rives 2010, pp. 249–251.

- ^ Van Dam 1985, p. 3.

- ^ Boyer 1992, p. 28.

- ^ a b Runciman 2004, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Boyd & Richerson 2010, p. 3792.

- ^ Runciman 2004, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 10.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 40.

- ^ a b Price 2012, p. 1.

- ^ Collar 2013, p. 149.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 12.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 83.

- ^ Collar 2013, p. 74.

- ^ Collar 2013, p. 7.

- ^ Rogers 2003, pp. 100–101, 109–111, 123.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 14.

- ^ Liu 2017, p. 46.

- ^ Parkin & Pomeroy 2007, p. 205.

- ^ Ulhorn 1883, pp. 2–44, 321.

- ^ Schmidt 1889, pp. 245–256.

- ^ Crislip 2005, p. 46.

- ^ a b Garrison 1993, p. 10.

- ^ Brown 2002.

- ^ Garrison 1993, p. 94.

- ^ Muir 2006, p. 231.

- ^ Wet 2015, p. 8; 195.

- ^ MacMullen 1986, pp. 324–326.

- ^ a b Wet 2015, pp. 10–13.

- ^ Koester 1998, A New Community.

- ^ Salzman 2009, p. x.

- ^ Meeks 1998.

- ^ Malcolm 2013, pp. 14–18, 27.

- ^ Meeks 2003, p. 79.

- ^ Judge 2010, p. 214.

- ^ a b Harper 2013, pp. 14–18.

- ^ Wet 2015, p. 10.

- ^ Wessels 2010, p. 143.

- ^ Wessels 2010, p. 166.

- ^ Wessels 2010, pp. 163–166.

- ^ Wessels 2010, p. 168.

- ^ Harper 2011, p. 483.

- ^ Combes 1998, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Tsang 2005, p. 2.

- ^ Wet 2015, p. 6.

- ^ Harper 2011, p. 18.

- ^ Tate 2008, p. 129.

- ^ Wet 2015, p. 276.

- ^ Wet 2015, p. 13.

- ^ Harper 2011, pp. 16, 22, 63, 72, 77–78, 214, 284–285, 293.

- ^ Wet 2015, p. 1.

- ^ MacMullen 1986, p. 325, n. 10.

- ^ Runciman 2004, pp. 9, 17–18.

- ^ a b c Fousek 2018, p. Gravity model.

- ^ Fousek 2018, p. Introduction.

- ^ Hopkins 1998, p. 202.

- ^ Collar 2013, p. 216, 289.

- ^ a b Fousek 2018, p. Discussion.

- ^ Collar 2013, p. 31.

- ^ a b Barabási & Albert 1999, p. 509-512.

- ^ a b c d Schor 2009, pp. 495–496.

- ^ Collar 2013, pp. 10–12.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Rogers 2003, p. 16.

- ^ Meeks 1993, p. 2.

- ^ Meeks 1993, p. 6.

- ^ Price 2012, p. paragraphs 5-8 section IV the Imperial Context.

- ^ Sittser 2019, p. 4.

- ^ Meeks 2002, p. 4.

- ^ Green 2010, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Trebilco 2017, pp. 85, 218.

- ^ Hopkins 1998, p. 187.

- ^ Richardson 2005, p. 259-266.

- ^ Praet 1992, p. 68;108.

- ^ Praet 1992, p. 16.

- ^ Safrai et al. 1974, pp. 117–119.

- ^ Safrai et al. 1974, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Fredriksen spread.

- ^ Praet 1992, p. 45–48.

- ^ a b c d Rogers 2003, p. 20.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 21.

- ^ Meeks 2002, p. 196.

- ^ Dodds 1990, p. 133.

- ^ MacCormack 1997, p. 655.

- ^ McKinion 2001, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 108.

- ^ Rogers 2003, pp. 17, 20.

- ^ Rogers 2003, pp. 174–176.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 177.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 100.

- ^ Rogers 2003, pp. 21, 100.

- ^ Collar 2013, pp. 4, 36, 157, 289.

- ^ a b Collar 2013, p. 18.

- ^ a b Collar 2013, p. 17.

- ^ Rogers 2003, pp. 201, 279, 354.

- ^ Collar 2013, pp. 25, 147–150.

- ^ Durand 1977, p. 268.

- ^ Collar 2013, pp. 25, 37.

- ^ Knox 2000, p. 78.

- ^ Allen 1962, p. 3.

- ^ McDowell 2016, pp. 177, 207, 233.

- ^ O'Mahony 2004, pp. 121–152.

- ^ Curtin, D. P.; Nath, Nithul. (May 2017). The Ramban Pattu. Dalcassian Press. ISBN 9781087913766.

- ^ Mathew, Chennattuserry & Bungalowparambil 2020, pp. 7–15.

- ^ a b Bays 2011, Ch. 1.

- ^ Neill 1957, p. 35.

- ^ Rogers 1959, p. 133.

- ^ Meeks 2002, p. 59; 131.

- ^ Stephenson 2010, pp. 5, 38–39.

- ^ Lieu 1999, p. 16.

- ^ Meeks 2002, p. 5.

- ^ MacDonald 2003, pp. 163, 167.

- ^ Cloke 1995, pp. 5–7.

- ^ Pomeroy 1995, p. xv.

- ^ Tulloch 2004, p. 302.

- ^ Meeks 2002, p. 20.

- ^ Meeks 2002, p. 6.

- ^ Meeks 2002, p. 10.

- ^ a b Meeks 2002, p. 11.

- ^ MacDonald 2003, pp. 157, 167–168, 184.

- ^ MacDonald 2003, pp. 167, 168.

- ^ Kraemer 1980, p. 305.

- ^ Kraemer 1980, pp. 306–307.

- ^ Milnor 2011, p. abstract.

- ^ a b MacDonald 2003, p. 169.

- ^ Nathan 2002, pp. 116, 120, 127.

- ^ Ng 2008, pp. 679–695.

- ^ Collar 2013, p. 23.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 265.

- ^ Rankin, Rankin & Rankin 1995, p. 200.

- ^ Crislip 2005, p. 1-3.

- ^ Gibbon 1776, Chapter 38.

- ^ Vaage 2006, p. 215.

- ^ Vaage 2006, p. 226.

- ^ Wessel 2016, p. 142.

- ^ Stark 1996, p. 204.

- ^ Crislip 2005, pp. 68–69, 99.

- ^ Crislip 2005, p. 103.

- ^ Koester 1998, Welfare Institutions.

- ^ Harper 2013, pp. 4, 7.

- ^ Langlands 2006, p. 10.

- ^ Harper 2013, p. 7.

- ^ Langlands 2006, pp. 10, 38.

- ^ Harper 2013, pp. 6, 7.

- ^ Collar Review 2015, p. 156-157.

- ^ Casson 1998, pp. 84–90.

- ^ Lee 2016, p. [page needed].

- ^ Cairns 1996, p. 87.

- ^ Plescia 1971, p. 124.

- ^ Frend 2014, pp. 393–394.

- ^ Schaff 1893, §2.

- ^ Schaff 1893, §22.

- ^ Kelhoffer 2010, pp. 6, 25, 203.

- ^ Knapp 2017, p. 206.

- ^ Hopkins 1998, p. 197.

- ^ Berend 2007, p. 21.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 297.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 354.

- ^ Van Eck 2011, p. 187.

- ^ Rogers 2003, p. 27.

- ^ a b Leithart 2010, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Doležal 2020, pp. 8–12.

- ^ Bayliss 2004, p. 243.

- ^ a b Drake 1995, p. 4.

- ^ a b Leithart 2010, p. 302.

- ^ Wiemer 1994, p. 523.

- ^ Drake 1995, p. 7–9.

- ^ Drake 1995, pp. 9, 10.

- ^ Leithart 2010, p. 304.

- ^ Brown 2003, p. 74.

- ^ Thompson 2005, p. 87,93.

- ^ Southern 2015, p. 455–457.

- ^ Salzman 2009, p. 17;201.

- ^ Novak 1979, p. 274.

- ^ Collar 2013, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Novak 1979, pp. 305, 312.

- ^ Salzman 2009, pp. xii, 14–15, 197, 199, 219.

- ^ Stark 1995, p. 153;230.

- ^ a b Salzman 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Scourfield 2007, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Markus 1990, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Clark 1992, pp. 543–546.

- ^ Leone 2013, pp. 13, 42.

- ^ Cameron 1993, p. 392–393.

- ^ Brown 1998, p. 645.

- ^ Brown 1998, p. 641.

- ^ Brown 1963, p. 284.

Bibliography

[edit]- Allen, Roland (1962). Missionary Methods: St. Paul's Or Ours? (reprint ed.). Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-1001-4.

- Barabási, Albert-László; Albert, Réka. (15 October 1999). "Emergence of scaling in random networks". Science. 286 (5439): 509–512. arXiv:cond-mat/9910332. Bibcode:1999Sci...286..509B. doi:10.1126/science.286.5439.509. MR 2091634. PMID 10521342. S2CID 524106.

- Bayliss, Richard (2004). Provincial Cilicia and the Archaeology of Temple Conversion. Oxford: Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-84171-634-3.

- Bays, Daniel H. (2011). A New History of Christianity in China. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-5954-8.

- Berend, Nora (2007). Christianization and the Rise of Christian Monarchy: Scandinavia, Central Europe and Rus' c.900–1200. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-46836-7.

- Boyd, Robert; Richerson, Peter J. (2010). "Transmission Coupling Mechanisms: Cultural Group Selection". Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences. 365 (1559): 3787–95. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0046. JSTOR 20789194. PMC 2981912. PMID 21041204.

- Boyer, Pascal (1992). "Explaining Religious Ideas: Elements of a Cognitive Approach". Numen. 39 (1): 27–57. doi:10.2307/3270074. JSTOR 3270074.

- Brown, Peter (1963). "Religious Coercion in the Later Roman Empire: The Case of North Africa". History. 48 (164). Wiley: 283–305. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1963.tb02320.x. JSTOR 24405550.

- Brown, Peter (2002). Poverty and Leadership in the Later Roman Empire. UPNE. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-58465-146-8.

- Brown, Peter (1998). "Christianization and religious conflict". In Averil Cameron; Peter Garnsey (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History XIII: The Late Empire, A.D. 337–425. Cambridge University Press. pp. 632–664. ISBN 978-0-521-30200-5.

- Brown, Peter (2003). The rise of Western Christendom : triumph and diversity, A.D. 200-1000 (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-0-631-22137-1.

- Cairns, Earle E. (1996). "Chapter 7:Christ or Caesar". Christianity Through the Centuries: A History of the Christian Church (Third ed.). Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-20812-9.

- Cameron, Averil (1993). The Later Roman Empire, AD 284-430 (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-51194-1.

- Casson, Lionel (1998). "Chapter 7 'Christ or Caesar'". Everyday Life in Ancient Rome (revised ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5991-5.

- Clark, Elizabeth A. (1992). "The End of Ancient Christianity". Ancient Philosophy. 12 (2): 543–546. doi:10.5840/ancientphil199212240.

- Cloke, Gillian (1995). This Female Man of God: Women and Spiritual Power in the Patristic Age, 350–450 AD. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-09469-6.

- Collar, Anna (2013). Religious networks in the Roman Empire: The spread of new ideas (illustrated, reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-04344-2.

- Collar, Anna (2007). "Network Theory and Religious Innovation". Mediterranean Historical Review. 22 (1): 149–162. doi:10.1080/09518960701539372. S2CID 144519653.

- Collar, Anna (2022). Networks and the Spread of Ideas in the Past: Strong Ties, Innovation and Knowledge Exchange. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-36847-7.

- Combes, I.A.H. (1998). The Metaphor of Slavery in the Writings of the Early Church: From the New Testament to the Beginning of the Fifth Century. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-85075-846-4.

- Crislip, Andrew T. (2005). From Monastery to Hospital: Christian Monasticism & the Transformation of Health Care in Late Antiquity. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11474-0.

- Dodds, Eric Robertson (1990). Pagan and Christian in an Age of Anxiety: Some Aspects of Religious Experience from Marcus Aurelius to Constantine (illustrated, reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38599-2.

- Doležal, Stanislav (2020). The Reign of Constantine, 306–337: Continuity and Change in the Late Roman Empire. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-97464-0.

- Drake, H. A. (1995). "Constantine and Consensus". Church History. 64 (1): 1–15. doi:10.2307/3168653. JSTOR 3168653. S2CID 163129848.

- Durand, John D. (1977). "Historical Estimates of World Population: An Evaluation". Population and Development Review. 3 (3): 253–296. doi:10.2307/1971891. JSTOR 1971891.

- Fousek, Jan; Kaše, Vojtěch; Mertel, Adam; Výtvarová, Eva; Chalupa, Aleš (2018). "Spatial constraints on the diffusion of religious innovations: The case of early Christianity in the Roman Empire". PLOS ONE. 13 (12): e0208744. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1308744F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208744. PMC 6306252. PMID 30586375.

- Fredriksen, Paula. "Spread of Christianity". The Great Appeal. PBS. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- Frend, William Hugh Clifford (15 April 2014). Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church: A Study of Conflict from the Maccabees to Donatus. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-62564-804-4.

- Garrison, Roman (1993). Redemptive Almsgiving in Early Christianity. Sheffield: JSOT Press. ISBN 978-1-85075-376-6.

- Gibbon, Edward (1776). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Vol. I: The Decline And Fall In The West.

- Gibbon, Edward (1906). "XX". In Bury, J.B. (ed.). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Vol. 3. Fred de Fau and Co.

- Green, Bernard (2010). Christianity in Ancient Rome: The First Three Centuries. A&C Black. p. 126-127. ISBN 978-0-567-03250-8.

- HARNETT, Benjamin (2017). "The Diffusion of the Codex". Classical Antiquity. 36 (2). University of California Press: 183–235. doi:10.1525/ca.2017.36.2.183. JSTOR 26362608.

- Harper, Kyle (2011). Slavery in the Late Roman World, AD 275–425. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511973451. ISBN 978-0-521-19861-5.

- Harper, Kyle (2013). From Shame to Sin: The Christian Transformation of Sexual Morality in Late Antiquity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-07277-0.

- Harris, William Vernon (2005). The Spread of Christianity in the First Four Centuries: Essays in Explanation. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-14717-1.

- Hopkins, Keith (1998). "Christian Number and Its Implications". Journal of Early Christian Studies. 6 (2): 185–226. doi:10.1353/earl.1998.0035. S2CID 170769034.

- Jordan, David P. (1969). "Gibbon's "Age of Constantine" and the Fall of Rome". History and Theory. 8 (1): 71–96. doi:10.2307/2504190. JSTOR 2504190.

- Judge, E.A. (2010). Alanna Nobbs (ed.). Jerusalem and Athens: Cultural Transformation in Late Antiquity. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-150572-0.

- Kelhoffer, James A. (2010). Persecution, Persuasion and Power: Readiness to Withstand Hardship as a Corroboration of Legitimacy in the New Testament. Vol. 270. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-150612-3.

- Koester, Helmut (April 1998). "The Great Appeal". The Great Appeal. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- Knapp, Robert (2017). The Dawn of Christianity: People and Gods in a Time of Magic and Miracles (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97646-7.

- Knox, John (2000). Hare, Douglas R. A. (ed.). Chapters in a Life of Paul (revised ed.). Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-281-5.

- Kraemer, Ross S. (1980). "The Conversion of Women to Ascetic Forms of Christianity". Signs. 6 (2): 298–307. doi:10.1086/493798. JSTOR 3173928. S2CID 143202380.

- Langlands, Rebecca (2006). Sexual Morality in Ancient Rome. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85943-1.

- Lee, A.Doug (2016). Pagans and Christians in Late Antiquity: A Sourcebook (Second ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-02031-3.

- Leithart, Peter J. (2010). Defending Constantine The Twilight of an Empire and the Dawn of Christendom. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-2722-0.

- Leone, Anna (2013). The End of the Pagan City: Religion, Economy, and Urbanism in Late Antique North Africa (illustrated ed.). OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-957092-8.

- Lieu, Judith M. (1999). "The'attraction of women'in/to early Judaism and Christianity: gender and the politics of conversion". Journal for the Study of the New Testament. 21 (72): 5–22. doi:10.1177/0142064X9902107202. S2CID 144475695.

- Liu, Jinyu (15 June 2017). "Urban Poverty in the Roman Empire: Material Conditions". In IV, Thomas R. Blanton; Pickett, Raymond (eds.). Paul and Economics: A Handbook. Fortress Press. pp. 23–56. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1kgqtgr. ISBN 978-1-5064-0604-6.

- MacCormack, Sabine (1997). "Sin, Citizenship, and the Salvation of Souls: The Impact of Christian Priorities on Late-Roman and Post-Roman Society". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 39 (4): 644–673. doi:10.1017/S0010417500020843. S2CID 144021596.

- MacDonald, Margaret Y. (2003). "Was Celsus Right? The Role of Women in the Expansion of Early Christianity". In David L. Balch; Carolyn Osiek (eds.). Early Christian Families in Context: An Interdisciplinary Dialogue. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 157–184. ISBN 978-0-8028-3986-2.

- MacMullen, Ramsay (1986). "What Difference Did Christianity Make?". Historia. 35 (3): 322–343.

- Malcolm, Matthew R. (2013). Paul and the Rhetoric of Reversal in 1 Corinthians: The Impact of Paul's Gospel on His Macro-Rhetoric. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03209-5.

- Markus, Robert Austin (1990). The End of Ancient Christianity (illustrated, reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33949-0.

- Mathew, K. S.; Chennattuserry, Joseph Chacko; Bungalowparambil, Antony (2020). St. Thomas and India: Recent Research. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-5064-6137-3.

- McDowell, Sean (2016). The Fate of the Apostles: Examining the Martyrdom Accounts of the Closest Followers of Jesus. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-03190-1.

- McKinion, Steve, ed. (2001). Life and Practice in the Early Church: A Documentary Reader. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-5648-5.

- Meeks, Wayne A. (1 January 1993). The Origins of Christian Morality: The First Two Centuries. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06513-8.

- Meeks, Wayne A. (April 1998). "Christians on Love". The Great Appeal. PBS. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- Meeks, Wayne A. (2002). In search of the early Christians : selected essays. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09142-7.

- Meeks, Wayne A. (2003). The First Urban Christians (second ed.). Yale University. ISBN 978-0-300-09861-7.

- Milnor, Kristina (2011). "Women in Roman Society". In Peachin, Michael (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Social Relations in the Roman World. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195188004.013.0029. ISBN 978-0-19-518800-4.

- Muir, Steven C. (2006). "10:"Look how they love one another" Early Christian and Pagan Care for the sick and other charity". Religious Rivalries in the Early Roman Empire and the Rise of Christianity. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-536-9.

- Nathan, Geoffrey (2002). The Family in Late Antiquity: The Rise of Christianity and the Endurance of Tradition (reprint ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-70668-6.

- Neill, Thomas Patrick; Schmandt, Raymond Henry (1957). History of the Catholic Church. Bruce Publishing Company.

- Ng, Esther Yue L. (October 2008). "Mirror Reading and Guardians of Women in the Early Roman Empire". Journal of Theological Studies. 59 (2): 679–695. doi:10.1093/jts/fln051.

- Novak, David M. (1979). "Constantine and the Senate: An Early Phase of the Christianization of the Roman Aristocracy". Ancient Society. 10: 271–310.

- O'Mahony, Anthony (2004). "Christianity in Modern Iraq". International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church. 4 (2): 121–142. doi:10.1080/1474225042000288939. S2CID 143924121.

- Parkin, Tim; Pomeroy, Arthur, eds. (2007). Roman Social History: A Sourcebook. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-42674-9.

- Plescia, Joseph (1971). "On the Persecution of the Christians in the Roman Empire". Latomus. 30 (1): 120–132. ISSN 0023-8856. JSTOR 41527858.

- Pomeroy, Sarah (1995). "Women in the Bronze Age and Homeric Epic". Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. New York: Schocken Books. ISBN 978-0-8052-1030-9.

- Praet, Danny (1992). "Explaining the Christianization of the Roman Empire. Older theories and recent developments". Sacris Erudiri. Jaarboek voor Godsdienstgeschiedenis. A Journal on the Inheritance of Early and Medieval Christianity. 23: 5–119.

- Price, Simon (2012). "Religious Mobility in the Roman Empire". The Journal of Roman Studies. 102: 1–19. doi:10.1017/S0075435812000056. JSTOR 41724963. S2CID 202300503.

- Rankin, David; Rankin, H. D.; Rankin, David Ivan (17 August 1995). Tertullian and the Church. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-48067-3.

- Richardson, Peter (2005). "8". Israel in the Apostolic Church (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02046-6.

- Rives, James B. (2010). "Graeco-Roman Religion in the Roman Empire: Old Assumptions and New Approaches". Currents in Biblical Research. 8 (2): 240–299. doi:10.1177/1476993X09347454. S2CID 161124650.

- Rogers, Everett M. (1959). "A Note on Innovators". Journal of Farm Economics. 41 (1): 132–134. doi:10.2307/1235208. JSTOR 1235208.

- Rogers, Everett M. (2003). Diffusion of Innovations (4th ed.). Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-926671-7.

- Runciman, W. G. (2004). "The Diffusion of Christianity in the Third Century AD as a Case-Study in the Theory of Cultural Selection". European Journal of Sociology. 45 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1017/S0003975604001365. S2CID 146353096.

- Russell, James C. (1996). The Germanization of Early Medieval Christianity: A Sociohistorical Approach to Religious Transformation (reprint ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510466-0.

- Safrai, Shemuel; Stern, Menahem; Flusser, David; van Unnik, Willem Cornelis, eds. (1974). "The Jewish Diaspora". The Jewish people in the first century. Historical geography, political history, social, cultural and religious life and institutions. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-90-232-1070-2.

- Salzman, Michele Renee (2009). The Making of a Christian Aristocracy: Social and Religious Change in the Western Roman Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00641-6.

- Schaff, Philip (1893). History of the Christian Church. Vol. II: Ante-Nicene Christianity. A.D. 100-325. Edinburgh: T.T. Clark.

- Schmidt, Charles (1889). "Chapter Five: The Poor and Unfortunate". The Social Results of Early Christianity. London, England: William Isbister Ltd. pp. 245–256. ISBN 978-0-7905-3105-2.

- Schor, Adam M. (2009). "Conversion by the numbers: Benefits and pitfalls of quantitative modelling in the study of early Christian growth". Journal of Religious History. 33 (4): 472–498. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9809.2009.00826.x.

- Schwartz, Seth (2005). "Chapter 8: Roman Historians and the Rise of Christianity: The School of Edward Gibbon". In Harris, William Vernon (ed.). The Spread of Christianity in the First Four Centuries: Essays in Explanation. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-14717-1.

- Scourfield, J. H. D. (2007). Texts and Culture in Late Antiquity: Inheritance, Authority, and Change. ISD LLC. ISBN 978-1-910589-45-8.

- Sittser, Gerald L. (2019). Resilient Faith: How the Early Christian "Third Way" Changed the World. Brazos Press. ISBN 978-1-4934-1998-2.

- Southern, Patricia (2015). The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine (second, revised ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-49694-6.

- Stark, Rodney (1995). "Reconstructing the Rise of Christianity: The Role of Women". Sociology of Religion. 56 (3): 229–244. doi:10.2307/3711820. JSTOR 3711820.

- Stark, Rodney (1996). The Rise of Christianity: A Sociologist Reconsiders History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02749-4.

- Stephenson, Paul (2010). Constantine: Roman Emperor, Christian Victor. Abrams Press. ISBN 978-1-59020-324-8.

- Tate, Joshua C. (2008). "Christianity and the Legal Status of Abandoned Children in the Later Roman Empire". Journal of Law and Religion. 24 (1): 123–141. doi:10.1017/S0748081400001958. S2CID 146901894.

- Thompson, Glen L. (2005). "Constantius II and the First Removal of the Altar of Victory". In Jean-Jacques Aubert; Zsuzsanna Varhelyi (eds.). A Tall Order: Writing the Social History of the Ancient World – Essays in honor of William V. Harris. Munich: K.G. Saur. pp. 85–106. doi:10.1515/9783110931419. ISBN 978-3-598-77828-5.

- Trebilco, Paul Raymond (2017). Outsider Designations and Boundary Construction in the New Testament: Early Christian Communities and the Formation of Group Identity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-31132-8.

- Tsang, Sam (2005). From Slaves to Sons: A New Rhetoric Analysis on Paul's Slave Metaphors in His Letter to the Galatians. Peter Lang Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8204-7636-0.

- Tulloch, Janet (2004). "Art and Archaeology as an Historical Resource for the Study of Women in Early Christianity: An Approach for Analyzing Visual Data". Feminist Theology. 12 (3): 277–304. doi:10.1177/096673500401200303. S2CID 145361724.

- Ulhorn, Gerhard (1883). Christian Charity in the Ancient Church. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Vaage, Leif E. (2006). Religious Rivalries in the Early Roman Empire and the Rise of Christianity. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-536-9.

- Van Dam, Raymond (1985). "From Paganism to Christianity at Late Antique Gaza". Viator. 16: 1–20. doi:10.1484/J.VIATOR.2.301417.

- Van Der Horst, Pieter W. (2015). ""Religious Networks in the Roman Empire: The Spread of New Ideas by Anna Collar"". Classical World. 108 (2): 299–300. doi:10.1353/clw.2015.0018.

- Van Eck, Peter S.; Wander, Jager; Leeflang, Peter SH (2011). "Opinion leaders' role in innovation diffusion: A simulation study". Journal of Product Innovation Management. 28 (2): 187–203. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5885.2011.00791.x.

- Welch, John W.; Pulham, Kathryn Worlton (2000). "The Rise of Christianity: How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Movement Became the Dominant Religious Force in the Western World in a Few Centuries Rodney Stark". BYU Studies Quarterly. 39 (3): 197–204.

- Wessel, Susan (2016). Passion and Compassion in Early Christianity (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-12510-0.

- Wessels, G. Francois (2010). "The Letter to Philemon in the Context of Slavery in Early Christianity". In D. Francois Tolmie (ed.). Philemon in Perspective: Interpreting a Pauline Letter. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 143–168. doi:10.1515/9783110221749. ISBN 978-3-11-022173-2.

- Wet, Chris L. de (2015). Preaching Bondage: John Chrysostom and the Discourse of Slavery in Early Christianity. Oakland: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-28621-4.

- Wiemer, Hans-Ulrich (1994). "Libanius on Constantine". The Classical Quarterly. 44 (2): 511–524. doi:10.1017/S0009838800043962. ISSN 0009-8388. JSTOR 639654. S2CID 170876695.

- Williams, Michael A.; Cox, Collett; Jaffee, Martin, eds. (1992). "Religious innovation: An introductory essay". Innovation in religious traditions : essays in the interpretation of religious change. Religion and Society. Vol. 31. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 1–18. doi:10.1515/9783110876352.1. ISBN 978-3-11087-635-2.

- Woolf, Greg (2015). "Religious Innovation in the Ancient Mediterranean". Oxford research encyclopedia of religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.5. ISBN 978-0-19934-037-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Athanassiadi, Polymnia (November 1993). "Persecution and response in late paganism: the evidence of Damascius". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 113: 1–29. doi:10.2307/632395. JSTOR 632395. S2CID 161339208.

- Bourne, Frank C. (1972). "Reviewed Work: Social Status and Legal Privilege in the Roman Empire by Peter Garnsey". The American Journal of Philology. 93 (4). doi:10.2307/294354. JSTOR 294354.

- Bowman, Alan; Wilson, Andrew, eds. (2011). Settlement, Urbanization, and Population. OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-960235-3.

- Brown, Peter (2016). Treasure in Heaven: The Holy Poor in Early Christianity (Richard Lectures) (2nd Revised ed.). University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-3828-8.

- Egmond, Florike (1995). "The cock, the dog, the serpent, and the monkey. Reception and transmission of a Roman punishment, or historiography as history". International Journal of the Classical Tradition. 2 (2): 159–192. doi:10.1007/BF02678619. S2CID 162261726.

- Errington, R. Malcolm (1988). "Constantine and the Pagans". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 29 (3): 309–318. ISSN 0017-3916.

- Fögen, Thorsten; Lee, Mireille M. (2010). Bodies and Boundaries in Graeco-Roman Antiquity. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-021253-2.

- Fugger, Verena (2017). "Shedding Light on Early Christian Domestic Cult: Characteristics and New Perspectives in the Context of Archaeological Findings". Archiv für Religionsgeschichte. 18–19 (1): 201–236. doi:10.1515/arege-2016-0012. S2CID 194608580.

- Greenhalgh, P. A. L.; Eliopoulos, Edward (1985). Deep into Mani: Journey to the Southern Tip of Greece. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-13524-0.