Christian interpretations of Virgil's Eclogue 4

Eclogue 4, also known as the Fourth Eclogue, is the name of a Latin poem by the Roman poet Virgil. Part of his first major work, the Eclogues, the piece was written around 40 BC, during a time of brief stability following the Treaty of Brundisium; it was later published in and around the years 39–38 BC. The work describes the birth of a boy, a supposed savior, who once of age will become divine and eventually rule over the world. During late antiquity and the Middle Ages, a desire emerged to view Virgil as a virtuous pagan, and as such the early Christian theologian Lactantius, and St. Augustine—to varying degrees—reinterpreted the poem to be about the birth of Jesus Christ.

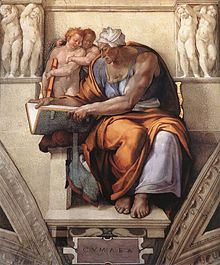

This belief persisted into the Medieval era, with many scholars arguing that Virgil not only prophesied Christ prior to his birth but also that he was a pre-Christian prophet. Dante Alighieri included Virgil as a main character in his Divine Comedy, and Michelangelo included the Cumaean Sibyl on the ceiling painting of the Sistine Chapel (a reference to the widespread belief that the Sibyl herself prophesied the birth of Christ, and Virgil used her prophecies to craft his poem). Modern scholars, such as Robin Nisbet, tend to eschew this interpretation, arguing that seemingly Judeo-Christian elements of the poem can be explained through means other than divine prophecy.

Background

[edit]The scholarly consensus is that Virgil began the hexameter Eclogues (or Bucolics) in 42 BC and it is thought that the collection was published around 39–8 BC (although this assertion is not without its detractors).[1] The Eclogues (from the Greek word for "selections") are a group of ten poems roughly modeled on the bucolic hexameter poetry ("pastoral poetry") of the Hellenistic poet Theocritus. The fourth of these Eclogues can be dated to around 40 BC, during a time when the Roman Civil war seemed to be coming to an end.[2] Eclogue 4 largely concerns the birth of a child (puer) who will become divine and eventually rule over the world.[3][4][5] Classicist H. J. Rose notes that the poem "is in a sense Messianic, since it contains a prophecy (whether meant seriously or not) of the birth of a wonder-child of more than mortal virtue and power, who shall restore the Golden Age".[6]

By the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries AD, Virgil had gained a reputation as a virtuous pagan, a term referring to pagans who were never evangelized and consequently during their lifetime had no opportunity to recognize Christ, but nevertheless led virtuous lives, so that it seemed objectionable to consider them damned.[7] Eventually, some Christians sought to reconcile Virgil's works with the supposed Christianity present in them. Consequently, during the Late Antiquity and beyond, many assumed that the puer referenced in the Fourth Eclogue was actually Jesus Christ.[8]

History

[edit]Early interpretations

[edit]

According to Classicist Domenico Comparetti, in the early Christian era, "A certain theological doctrine, supported by various passages of [Judeo-Christian] scripture, induced men to look for prophets of Christ among the Gentiles".[10] This inevitably resulted in early Christians looking to the works of Virgil—a famed poet who, even in late antiquity had immense clout in Roman society—for any sign of prophecy.[10] Eventually, there arose a belief that Virgil's Fourth Eclogue foretold the birth of Jesus, which seems to have first emerged during the 4th century.[11][12] The scholar Steven Benko proposes that this interpretation became so popular around this time (and not earlier) because it "provided [Constantinian Christians] a way to connect to non-Christian society and to give Christianity respectability."[13]

The first major proponent that the poem was prophetic was likely the early Christian writer Lactantius, who served as Constantine the Great's religious advisor.[12] In a chapter of his book, Divinae Institutiones (The Divine Institutes), entitled "Of the Renewed World", Lactantius quotes the Eclogue and argues that it refers to Jesus's awaited return at the end of the millennium. He further claims that "the poet [i.e. Virgil] foretold [the future coming Christ] according to the verses of the Cumaean Sibyl" (that is, the priestess presiding over the Apollonian oracle at Cumae).[10][14][15][16] According to Sabine G. MacCormack, this quote seems to suggest that while Lactantius believed the poem was a prophecy, he did not necessarily believe that Virgil himself was a prophet, as the poet was merely "reflect[ing] what the Sybil of Cumae and the Erythraean Sibyl had said long before [he] wrote."[17][nb 1]

Constantine himself also believed the poem could be interpreted as a prophecy about Christ. Many copies of the Roman historian Eusebius's Vita Constantini (The Life of Constantine) also contain a transcript of a speech made by the emperor at a Good Friday sermon during the First Council of Nicaea (AD 325),[4][12][19][20] in which the emperor re-imagines almost the entire poem line-by-line as a Christian portent (although a few are omitted because they overtly reference pagan characters and concepts). Some of Constantine's interpretations are obvious: he argues that the virgo in line 6 is a reference to the Blessed Virgin Mary, the puer in lines 8, 18, 60, and 62 to Christ, and the serpent in line 24 to the Serpent of Evil. Others are more subjective: For instance, the lions in line 22 represent, to the emperor, those who persecuted Christians, and the Assyrian flower in line 25 represents the race of people, i.e. the Assyrians, who were "leader[s] in the faith of Christ".[4][11] The emperor also interpreted the reference to Achilles fighting against Troy in lines 34-36 as an allegory for Christ (the "new" Achilles) battling evil (the "new" Troy). Finally, Constantine proposed that lines 37–59 do not refer the birth of a normal, mortal child, but rather to a being who "mortal parents have not smiled upon": in other words, Jesus Christ, who, according to Christian scripture, "had no parents in the usual sense".[9] However, Constantine differed from Lactantius in his opinion of Virgil, arguing that, given all the supposed allusions in this poem, Virgil surely "wrote with full knowledge that he was foretelling Christ", but he "expressed himself darkly and introduced the mention of [Roman] deities to avoid affronting the pagans and provoking the anger of the authorities."[11]

Several decades later, Church Father Augustine of Hippo expressed his belief that Virgil was one of many "Gentile ... prophets" who by divine grace had prophesied Christ's birth.[10][19][21] Echoing the sentiment of Lactantius, he wrote that the mention of Cumae in line 4 was a likely reference to the supposed Sibylline prophecy concerning Christ. However, Augustine, reasoned that while Virgil may have prophesied the birth and coming of Christ, it was likely that he did not understand the true meaning of what he himself was writing.[22][23]

The opinion that Eclogue 4 was a reference to the coming of Jesus was not universally held by early members of the early Church, however. St. Jerome, an early Church Father now remembered best for translating the Bible into Latin, specifically wrote that Virgil could not have been a Christian prophet because he never had the chance to accept Christ. Jerome further derided anyone who held Virgil as a pre-Christian prophet, calling such a belief childish and claiming that it was just as ridiculous as Christian cento poems.[10][19][24] But regardless of his exact feelings, the classicist Ella Bourne notes that the mere fact Jerome responded to the belief is a testament to its pervasiveness and popularity during that time.[24]

Medieval interpretations

[edit]

In the early part of the sixth century, Latin grammarian Fabius Planciades Fulgentius made a passing reference to the supposed prophetic nature of the Fourth Eclogue, noting: In quarta vaticinii artem adsumit ("In the Fourth [Eclogue], [Virgil] takes up the art of prophecy").[24] However, his view seems to have been a bit nuanced, and in one of his books, he wrote that "no one is permitted to know all the truth except ... Christians, on whom shines the sun of truth. But [Virgil did] not come as an expositor well-versed in [the] books of Scripture."[25][26][nb 2] Craig Kallendorf writes that this indicated Fulgentius's belief that "there [were] limits to what ... Virgil knew about Christianity."[25]

According to legend, Donatus, a bishop of Fiesole in the ninth century, quoted the seventh line of the poem as part of a confession of his faith prior to his death.[27] During the same century, Agnellus, the archbishop of Ravenna, referenced the poem, noting that it was evidence that the Holy Spirit had spoken through both Virgil and the Sybil. The monk Christian Druthmar also makes use of the seventh line in his commentary on Matthew 20:30.[28]

In the eleventh century, Virgil began appearing in plays, such as one particular Christmas work wherein the poet is the last "prophet" called on to give testimony concerning Christ. According to Bourne, the play was particularly popular, and philologist Du Cange gives mention of a similar play performed at Rouen. Virgil and his purported prophecy even found itself in the Wakefield Mystery Plays.[29] Around this time, Eclogue 4 and Virgil's supposed prophetic nature had saturated the Christian world; references to the poem are made by Abelard, the Bohemian historian Cosmos, and Pope Innocent III in a sermon. The Gesta Romanorum, a Latin collection of anecdotes and tales that was probably compiled about the end of the 13th century or the beginning of the 14th, confirms that the eclogue was pervasively associated with Christianity.[30]

Virgil eventually became a fixture of Medieval ecclesiastic art, appearing in churches, chapels, and even cathedrals, sometimes depicted holding a scroll with a select passage from the Fourth Eclogue on it.[31] At other times, he "figured in sacred pictures ... in the company of David, Isaiah and other [Judeo-Christian] prophets".[27] Virgil's popularity in Medieval art is likely why Michelangelo included the Cumaean Sibyl on the ceiling painting of the Sistine Chapel, for, according to Paul Barolsky, the Sibyl's presence "evokes her song in Virgil [i.e. the Fourth Eclogue], prophesying spiritual renewal through the coming of Christ—the very theme of the ceiling."[32] Barolsky also points out that Michelangelo painted the Sibyl in close proximity to the prophet Isaiah; thus, the painter drew a visual comparison between the similar nature of their prophecies.[32]

This association between Virgil and Christianity reached a fever pitch in the fourteenth century, when the Divine Comedy was published; the work, by Dante Alighieri, prominently features Virgil as the main character's guide through Hell.[33] Notably, in the second book Purgatorio, Dante and Virgil meet the poet Statius, who, having "read a hidden meaning in lines of Virgil's own" (that is, Eclogue 4.5–7), was allowed passage into Purgatory, and eventually Heaven.[4][34][35] (This legend had developed earlier in the Middle Ages, but Dante's reference popularized it.)[27] Bourne argues that Dante's inclusion of Statius's conversion through Virgil's poem is proof enough that Dante, like those before him, believed Virgil to have been an unknowing Christian prophet.[34] Kallendorf notes that because writing the lines did not save Virgil, but reading them saved Statius, "Dante ... must have located the Christinization of Eclogue 4 in the reader rather than the writer."[35]

In the fifteenth century, a popular story concerning Secundian, Marcellian and Verian—who started out as persecutors of Christians during the reign of the Roman emperor Decius—emerged. The story claims that the trio were alarmed by the calm manner in which their Christian victims died, and so they turned to literature and chanced upon Eclogue 4, which eventually caused their conversions and martyrdom.[34] Around this time, the famed astrologer and humanist philosopher Marsilio Ficino seems to have accepted that the poem was a prophecy, too.[27]

Later interpretations

[edit]The French writer René Rapin (1621–1687) was fascinated with the potential connection between Virgil and Christianity, and used the Fourth Eclogue as an artistic influence, basing many of his lines in his own Sixth Eclogue on Virgil's work. One of the more overt modern references to the Fourth Eclogue, Virgil, and Christianity, appears in Alexander Pope's 1712 poem, Messiah. Bourne wrote that the work "shows clearly that [Pope] believed that Virgil's poem was based on a Sibylline prophecy".[36] Robert Lowth seems also to have held this opinion, noting, by way of Plato, that the poem contains references made "not by men in their sober senses, but [by] the God himself".[36] In the mid-19th century, Oxford scholar John Keble claimed: Taceo si quid divinius ac sanctius (quod credo equidem) adhaeret istis auguriis ("I am silent about whether something more divine and sacred—which is what I, in fact, believe—clings to these prophecies").[37]

Modern views

[edit]By the turn of the 20th century, most scholars had abandoned the idea that the Fourth Eclogue was prophetic, although "there [were] still some to be found who", in the words of Comparetti, "[took] this ancient farce seriously."[38] Robin Nisbet has argued that the supposed Christian nature of the poem is a by-product of Virgil's creative references to disparate religious texts; Nisbet proposes that Virgil probably appropriated some elements used in the poem from Jewish mythology by means of Eastern oracles. In doing so, he adapted these ideas to Western (which is to say, Roman) modes of thought.[39]

See also

[edit]- Interpretatio Christiana, the adaptation of non-Christian elements of culture or historical facts to the worldview of Christianity

Notes

[edit]- ^ Sabine MacCormack, citing R. G. M. Nisbet, notes that Lactantius's belief "was not without objective merit", as it is possible that Virgil was appropriating aspects of Judeo-Christians prophecy by way of Eastern oracles.[18]

- ^ Fulgentius's original Latin is written as if Virgil himself were saying it. The text in this article has been amended so that it is in third rather than first person.

References

[edit]- ^ Fowler (1996), p. 1602.

- ^ Morwood (2008), p. 5.

- ^ Rose (1924), p. 114.

- ^ a b c d Bourne (1916), p. 391.

- ^ Davis (2010), p. x.

- ^ Rose (1924), p. 113.

- ^ Vitto (1989), pp. 36–49.

- ^ Conte (1999), p. 267.

- ^ a b Bourne (1916), pp. 390–2.

- ^ a b c d e Comparetti (1895), p. 101.

- ^ a b c Comparetti (1895), p. 100.

- ^ a b c Kallendorf (2015), 51.

- ^ Kallendorf (2015), 52.

- ^ Bourne (1916), p. 392.

- ^ Pelikan (1999), p. 37.

- ^ Lactantius, Divinae Institutiones 7.24.

- ^ MacCormack (1998), p. 25.

- ^ MacCormack (1998), p. 25, note 82.

- ^ a b c Pelikan (1999), p. 36.

- ^ Constantine apud Eusebius, Oratio ad coetum sanctorum 19–21.

- ^ Augustine, Epistolae ad Romanos inchoata expositio 1.3.

- ^ Bourne (1916), p. 392–393.

- ^ Augustine, De civitate Dei, 10.27.

- ^ a b c Bourne (1916), p. 393.

- ^ a b Kallendorf (2015), 54.

- ^ Fabius Planciades Fulgentius, Expositio Virgilianae continentiae secundum philosophos moralis, 23–24.

- ^ a b c d Comparetti (1895), p. 102.

- ^ Bourne (1916), pp. 393–4.

- ^ Bourne (1916), pp. 394–5.

- ^ Bourne (1916), pp. 395–6.

- ^ Bourne (1916), pp. 396–7.

- ^ a b Barolsky (2007), p. 119.

- ^ Bourne (1916), pp. 397–8.

- ^ a b c Bourne (1916), p. 398.

- ^ a b Kallendorf (2015), 56.

- ^ a b Bourne (1916), p. 399.

- ^ Bourne (1916), p. 400.

- ^ Comparetti (1895), p. 103.

- ^ Nisbet (1978), p. 71.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bourne, Ella (April 1916). "The Messianic Prophecy in Vergil's Fourth Eclogue". The Classical Journal. 11 (7). Classical Association of the Middle West and South: 390–400. JSTOR 3287925.

- Conte, Gian Biagio (1999). Latin Literature: A History. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801862533.

- Fowler, Don (1996). "Virgil (Publius Vergilius Maro)". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (3 ed.). Oxford. ISBN 9780198661726.

- Gregson, Davis (2010). "Introduction". Virgil's Eclogues. Translated by Krisak, Len. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812205367.

- Kallendorf, Craig (2015). The Protean Virgil: Material Form and the Reception of the Classics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198727804.

- MacCormack, Sabine (1998). The Shadows of Poetry: Vergil in the Mind of Augustine. Oakland, California: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520920279.

- Morwood, James (2008). "Eclogues" (PDF). Virgil, A Poet in Augustan Rome. Cambridge University Press. pp. 5, 9–10. ISBN 9780521689441.

- Nisbet, R. G. M. (1978). "Virgil's Fourth Eclogue: Easterners and Westerners". Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. 25 (1). Institute of Classical Studies: 59–78. doi:10.1111/j.2041-5370.1978.tb00385.x.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav (1999). Jesus Through the Centuries: His Place in the History of Culture. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300079876.

- Rose, H. J. (1924). "Some Neglected Points in the Fourth Eclogue". The Classical Quarterly. 18 (3/4). Classical Association: 113–118. doi:10.1017/S0009838800006960. S2CID 170727145.

- Vitto, Cindy (1989). The Virtuous Pagan in Middle English Literature. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 9780871697950.

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Bourne, Ella (April 1916). "The Messianic Prophecy in Vergil's Fourth Eclogue". The Classical Journal. 11 (7). Classical Association of the Middle West and South: 390–400. JSTOR 3287925.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Bourne, Ella (April 1916). "The Messianic Prophecy in Vergil's Fourth Eclogue". The Classical Journal. 11 (7). Classical Association of the Middle West and South: 390–400. JSTOR 3287925.

External links

[edit] English Wikisource has original text related to this article: English translation of Eclogue 4

English Wikisource has original text related to this article: English translation of Eclogue 4- Full Latin text of Eclogue 4, courtesy of the Perseus Project.