Kris Kristofferson

Kris Kristofferson | |

|---|---|

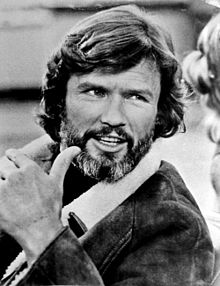

Kristofferson in 1978 | |

| Born | Kristoffer Kristofferson June 22, 1936 Brownsville, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | September 28, 2024 (aged 88) Hana, Hawaii, U.S. |

| Education | |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1959–2021 |

| Works | |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 8 |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | The Highwaymen |

| Website | kriskristofferson |

Kristoffer Kristofferson (June 22, 1936 – September 28, 2024) was an American country music singer, songwriter, and actor. He was a pioneering figure in the outlaw country movement of the 1970s, moving away from the polished Nashville sound and toward a more raw, introspective style. During the 1970s, he also embarked on a successful career as a Hollywood actor.

Kristofferson released his debut album Kristofferson in 1970. Among his songwriting credits are "Me and Bobby McGee", "For the Good Times", "Sunday Mornin' Comin' Down", and "Help Me Make It Through the Night", all of which became hits for other artists. Kristofferson was also a member of the country music supergroup the Highwaymen between 1985 and 1995. He has charted 12 times on the American Billboard Hot Country Songs charts; his highest peaking singles there are "Why Me" and "Highwayman", which reached number one in 1973 and 1985, respectively. He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2004 and received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2014. He was a three-time Grammy Award winner, out of 13 total nominations.[1]

As an actor, he became known for his roles in Cisco Pike (1972), Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), Blume in Love (1973), Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore (1974), and A Star Is Born (1976); for the latter, he earned a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy. He was also nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Score for the film Songwriter (1984). His acting career waned somewhat following his role in the box office bomb Heaven's Gate (1980), but he continued to act in films such as Stagecoach (1986), Lone Star (1996), and the Blade film trilogy (1998–2004).

Early life and education

[edit]Kristoffer Kristofferson was born in Brownsville, Texas, to Mary Ann (née Ashbrook) and Lars Henry Kristofferson, a U.S. Army Air Corps officer (later a U.S. Air Force major general).[2] During Kristofferson's childhood, his father encouraged him to pursue a military career.[3]

San Mateo, California

[edit]Kristofferson moved around frequently as a youth because of his father's military service, and the family settled in San Mateo, California.[4] After graduating from San Mateo High School in 1954, he enrolled at Pomona College, hoping to become a writer. His early writing included prize-winning essays: "The Rock" and "Gone Are the Days" were published in The Atlantic Monthly. These stories touch on the roots of Kristofferson's passions and concerns. "The Rock" is about a geographical feature resembling the form of a woman, while the latter was about a racial incident.[5]

At the age of 17, Kristofferson took a summer job with a dredging contractor on Wake Island in the western Pacific Ocean. He called it "the hardest job I ever had".[6]

Pomona College

[edit]Kristofferson attended Pomona College and experienced his first national exposure in 1958, appearing in the March 31 issue of Sports Illustrated for his achievements in collegiate rugby union, American football, and track and field.[7] He and his classmates revived the Claremont Colleges Rugby Club in 1958, and it remains a Southern California rugby institution. Kristofferson graduated in 1958 with a Bachelor of Arts degree, summa cum laude, in literature. He was elected to Phi Beta Kappa his junior year. In a 2004 interview with Pomona College Magazine, Kristofferson mentioned philosophy professor Frederick Sontag as an important influence in his life.[8]

In 1973, Kristofferson received an honorary doctorate in fine arts from Pomona College during Alumni Weekend, accompanied by fellow performers Johnny Cash and Rita Coolidge. His award was presented to him by his aforementioned mentor, Professor Sontag.[9]

University of Oxford

[edit]In 1958, Kristofferson was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship to the University of Oxford,[10] studying at Merton College.[11] While at Oxford, he was awarded a Blue for boxing,[11] played rugby for his college, and began writing songs. At Oxford, he became acquainted with fellow Rhodes scholar, art critic, and poet Michael Fried. With the help of his manager, Larry Parnes, Kristofferson recorded for Top Rank Records under the name Kris Carson. Parnes was working to sell Kristofferson as "a Yank at Oxford" to the British public; Kristofferson was willing to accept that promotional approach if it helped his singing career, which he hoped would enable him to progress toward his goal of becoming a novelist.[12]

This early phase of his music career was unsuccessful.[13] In 1960, Kristofferson graduated with a B.Phil. in English literature.[11][14][15] In 1961, he married his longtime girlfriend, Frances "Fran" Mavia Beer.[11]

Military service

[edit]Kristofferson, under pressure from his family, joined the U.S. Army and was commissioned as a second lieutenant, attaining the rank of captain. He became a helicopter pilot after receiving flight training at Fort Rucker, Alabama. He also completed Ranger School.[16] During the early 1960s, he was stationed in West Germany as a member of the 8th Infantry Division.[17] During this time, he resumed his music career and formed a band. In 1965, after his tour in West Germany ended, Kristofferson was given an assignment to teach English literature at West Point.[18] Instead, he decided to leave the Army and pursue songwriting. His family disowned him because of his career decision; sources are unclear on whether they reconciled.[19][20][21] They saw it as a rejection of everything they stood for, although Kristofferson says he is proud of his time in the military and received the Veteran of the Year Award at the 2003 American Veterans Awards ceremony.[22][23]

Career

[edit]After leaving the army in 1965, Kristofferson moved to Nashville. Struggling for success in music, he worked at odd jobs in the meantime while burdened with medical expenses resulting from his son's defective esophagus. He and his wife divorced in 1968.[24]

Kristofferson got a job sweeping floors at Columbia Recording Studios in Nashville. He met June Carter there and asked her to give Johnny Cash a tape of his. She did, but Cash put it on a large pile with others. He also worked as a commercial helicopter pilot for south Louisiana firm Petroleum Helicopters International (PHI), based in Lafayette, Louisiana. Kristofferson recalled of his days as a pilot, "That was about the last three years before I started performing, before people started cutting my songs. I would work a week down here [in south Louisiana] for PHI, sitting on an oil platform and flying helicopters. Then I'd go back to Nashville at the end of the week and spend a week up there trying to pitch the songs, then come back down and write songs for another week. I can remember "Help Me Make It Through the Night" I wrote sitting on top of an oil platform. I wrote "Bobby McGee" down here, and a lot of them [in south Louisiana]."[25]

Weeks after giving Carter his tapes, Kristofferson landed a helicopter in Cash's front yard, gaining his full attention.[26] A story about Kristofferson having a beer in one hand and some songs in the other upon arrival was reputed, but was later refuted, with Kristofferson saying, "It was still kind of an invasion of privacy that I wouldn't recommend. To be honest, I don't think he was there. John had a pretty creative memory."[27] Upon hearing "Sunday Mornin' Comin' Down", however, Cash decided to record it, and in 1970 Kristofferson won Song of the Year for the song at the Country Music Association Awards.[28]

In 1966, Dave Dudley released a successful Kristofferson single, "Viet Nam Blues." In 1967, Kristofferson signed to Epic Records and released a single, "Golden Idol/Killing Time," but the song was not successful. Within the next few years, more Kristofferson originals hit the charts, performed by Roy Drusky ("Jody and the Kid"); Billy Walker & the Tennessee Walkers ("From the Bottle to the Bottom"); Ray Stevens ("Sunday Mornin' Comin' Down"); Jerry Lee Lewis ("Once More with Feeling"); Faron Young ("Your Time's Comin'"); and Roger Miller ("Me and Bobby McGee", "Best of all Possible Worlds", and "Darby's Castle"). He was successful as a performer following Johnny Cash's introduction of him at the Newport Folk Festival.[29]

In 1971, Janis Joplin, who had dated Kristofferson, had a number one hit with "Me and Bobby McGee" from her posthumous album Pearl. It stayed on the number-one spot on the charts for weeks. More hits followed from others: Ray Price ("I'd Rather Be Sorry"); Joe Simon ("Help Me Make It Through the Night"); Bobby Bare ("Please Don't Tell Me How the Story Ends"); O. C. Smith ("Help Me Make It Through the Night"); Jerry Lee Lewis ("Me and Bobby McGee"); Patti Page ("I'd Rather Be Sorry"); and Peggy Little ("I've Got to Have You"). Country music performer Kenny Rogers recorded some of Kristofferson's songs, including a version of "Me and Bobby McGee" in 1969 with the First Edition for the Ruby, Don't Take Your Love To Town album.[citation needed]

Kristofferson released his second album—The Silver Tongued Devil and I—in 1971. It included "Lovin' Her Was Easier (than Anything I'll Ever Do Again)". This success established Kristofferson's career as a recording artist. Soon after, Kristofferson made his acting debut in The Last Movie (directed by Dennis Hopper), and appeared at the Isle of Wight Festival. A portion of his Isle of Wight performance is featured on the three disc compilation, The First Great Rock Festivals of the Seventies. In 1971, he acted in Cisco Pike, and released his third album, Border Lord. The album was all-new material and sales were sluggish. He also swept the Grammy Awards that year with numerous songs nominated, winning country song of the year for "Help Me Make It Through the Night". Kristofferson's 1972 fourth album, Jesus Was a Capricorn, initially had slow sales, but the third single, "Why Me", was a success and significantly increased album sales. It sold over one million copies, and was awarded a gold disc by the RIAA on November 8, 1973.[30]

In 1972, Kristofferson appeared with Rita Coolidge on British TV on BBC's The Old Grey Whistle Test, performing "Help Me Make It Through the Night". Also in 1972, Al Green released his version of "For the Good Times" on the album I'm Still in Love with You.[31]

Film

[edit]For the next several years, Kristofferson focused on acting. He appeared in Cisco Pike (1972) with Gene Hackman; Blume in Love (1973), directed by Paul Mazursky; three Sam Peckinpah films: Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974), and Convoy (1978); and Michael Ritchie's Semi-Tough (1977) with Burt Reynolds. He continued acting in Martin Scorsese's Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore (1974), Vigilante Force (1976), The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea (1976), and the romantic drama A Star Is Born (1976) with Barbra Streisand, for which he received a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor. At the peak of his box office power, Kristofferson turned down William Friedkin's Sorcerer (1977) and the romantic war film Hanover Street (1979). Despite his success with Streisand, Kristofferson's solo musical career headed downward with his non-charting ninth album, Shake Hands with the Devil. His next film, the two-part 1979 NBC-TV movie Freedom Road, did not get good ratings.[citation needed]

Kristofferson was next cast in the lead role as the enigmatic Sheriff James Averill in Michael Cimino's bleak and sprawling 1980 anti-Western Heaven's Gate. Despite being a scandalous studio-bankrupting and industry-changing failure at the time (it cost Kristofferson his Hollywood A-list status), the film gained critical recognition in subsequent years. In 1981, he co-starred with Jane Fonda in Rollover, directed by Alan J. Pakula. In 1986, he starred in The Last Days of Frank and Jesse James with Johnny Cash and Flashpoint with Treat Williams in 1984, directed by William Tannen. This was followed, in 1985, by the neo-noir thriller Trouble In Mind co-starring Keith Carradine and Lori Singer. In 1987, Kristofferson starred in the seven-episode TV series Amerika with Robert Urich and Christine Lahti. In 1989, he was the male lead in the film Millennium with Cheryl Ladd. In 1996, he earned a supporting role as Charlie Wade, a corrupt South Texas sheriff in John Sayles' Lone Star, a film nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. In 1997, he co-starred in the film Fire Down Below with Steven Seagal.[32]

In 1998, Kristofferson took a role in the film Blade, alongside Wesley Snipes, as Blade's mentor Abraham Whistler. He reprised the role in Blade II (2002) and again in Blade: Trinity (2004). In 1998 he starred in Dance with Me along with Vanessa Williams and Chayanne. In 1999, he co-starred with Mel Gibson in Payback. He played rancher Rudolph Meyer in Molokai: The Story of Father Damien (1999). He was then in the 2001 Tim Burton version of Planet of the Apes. He also played the title character "Yohan" as an old man in the Norwegian film Yohan: The Child Wanderer. He co-starred in the 2011 film Dolphin Tale and its 2014 sequel, Dolphin Tale 2. In 2012, Kristofferson was in Joyful Noise with longtime friend Dolly Parton. In 2013, Kristofferson co-starred in The Motel Life, as well as Angels Sing with Willie Nelson and Lyle Lovett. In 2006, Kristofferson starred with Geneviève Bujold in the film Disappearances about whiskey running from Quebec to the U.S. during the Great Depression.[33]

Mid-career

[edit]In the course of his singing success during the early 1970s, Kristofferson met singer Rita Coolidge. They married in 1973 and released an album titled Full Moon, another success buoyed by numerous hit singles and Grammy nominations. His fifth album, Spooky Lady's Sideshow, released in 1974, was a commercial failure, setting the trend for most of the rest of his musical career. Artists such as Ronnie Milsap and Johnny Duncan continued to record Kristofferson's material with success, but his distinctively rough voice and anti-pop sound kept his own audience to a minimum. Meanwhile, more artists took his songs to the top of the charts, including Willie Nelson, whose 1979 LP release of (Willie Nelson) Sings Kristofferson reached number five on the U.S. Country Music chart and certified Platinum in the U.S.[citation needed]

In 1979, Kristofferson traveled to Havana, Cuba, to participate in the historic Havana Jam festival that took place on March 2–4, alongside Rita Coolidge, Stephen Stills, the CBS Jazz All-Stars, the Trio of Doom, Fania All-Stars, Billy Swan, Bonnie Bramlett, Mike Finnigan, Weather Report, and Billy Joel, plus an array of Cuban artists such as Irakere, Pacho Alonso, Tata Güines, and Orquesta Aragón. His performance is captured on Ernesto Juan Castellanos's documentary Havana Jam '79.[citation needed]

On November 18, 1979, Kristofferson and Coolidge appeared on The Muppet Show, where Kristofferson sang "Help Me Make It Through the Night" with Miss Piggy, Coolidge sang "We're All Alone" with forest animals, and the pair sang "Song I'd Like to Sing" with the Muppet monsters. They divorced in 1980.[34]

Later years

[edit]In 1982, Kristofferson joined Willie Nelson, Dolly Parton, and Brenda Lee on The Winning Hand, a double album consisting of remastered and updated performances of recordings the four artists had made for the Monument label during the mid-1960s; the album reached the top ten on the U.S. country album charts. He married again, to Lisa Meyers, and concentrated on films for a time, appearing in the 1984 releases The Lost Honor of Kathryn Beck, Flashpoint, and Songwriter. Nelson and Kristofferson both appeared in Songwriter, and Kristofferson was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Score. The album Music from Songwriter, featuring Nelson-Kristofferson duets, was a country success.[citation needed]

Nelson and Kristofferson continued their partnership, and added Waylon Jennings and Johnny Cash to form the supergroup the Highwaymen. Their first album, Highwayman, was a success, and the supergroup continued working together for a time. The single from the album, also entitled "Highwayman", written by Jimmy Webb (and originally recorded by him in 1977), was awarded the ACM's single of the year in 1985.[35] In 1985, Kristofferson starred in Trouble in Mind and released Repossessed, a politically aware album that was a country success, particularly "They Killed Him" (also performed by Bob Dylan), a tribute to his heroes, including Martin Luther King Jr., Jesus, and Mahatma Gandhi.[36] Kristofferson also appeared in Amerika at about the same time, a miniseries that attempted to depict life in America under Soviet control.[37]

In spite of the success of Highwayman 2 in 1990, Kristofferson's solo recording career slipped significantly in the early 1990s, though he continued to record successfully with the Highwaymen. Lone Star (1996 film by John Sayles) reinvigorated Kristofferson's acting career, and he soon appeared in Blade, Blade II, Blade: Trinity, A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries, Fire Down Below, Tim Burton's remake of Planet of the Apes, Chelsea Walls, Payback, The Jacket, and Fast Food Nation.[citation needed]

The Songwriters Hall of Fame inducted Kristofferson in 1985, as had the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame earlier, in 1977. In 1999, The Austin Sessions was released, an album on which Kristofferson reworked some of his favorite songs with the help of artists such as Mark Knopfler, Steve Earle, and Jackson Browne. Shortly after the album's release, he underwent coronary artery bypass surgery.[38]

In 2003, Broken Freedom Song was released, a live album recorded in San Francisco. That year, he received the "Spirit of Americana" free speech award from the Americana Music Association.[39] In 2004, he was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. On October 21, 2005, the movie Dreamer was released, in which Kristofferson played the role of "Pop", a retired thoroughbred horse trainer. The movie was inspired by the true story of the mare Mariah's Storm which won the Turfway Breeders Cup Classic. In 2006, he received the Johnny Mercer Award from the Songwriters Hall of Fame and released his first album full of new material in 11 years; This Old Road. On April 21, 2007, Kristofferson won CMT's Johnny Cash Visionary Award. Rosanne Cash, Cash's daughter, presented the honor during the April 16 awards show in Nashville. Previous recipients include Cash, Hank Williams Jr., Loretta Lynn, Reba McEntire, and the Dixie Chicks. "John was my hero before he was my friend, and anything with his name on it is really an honor in my eyes," Kristofferson said during a phone interview. "I was thinking back to when I first met him, and if I ever thought that I'd be getting an award with his name on it, it would have carried me through a lot of hard times."[40]

In July 2007, Kristofferson was featured on CMT's Studio 330 Sessions where he played many of his hits.[citation needed]

On June 13, 2008, Kristofferson performed an acoustic in-the-round set with Patty Griffin and Randy Owen (Alabama) for a special taping of a PBS songwriters series aired in December. Each performer played five songs. Kristofferson's set included "The Best of All Possible Worlds", "Darby's Castle", "Casey's Last Ride", "Me and Bobby McGee", and "Here Comes that Rainbow Again". Taping was done in Nashville.[citation needed]

Kristofferson released a new album of original songs titled Closer to the Bone on September 28, 2009. It is produced by Don Was on the New West Records label. Prior to the release, Kristofferson remarked: "I like the intimacy of the new album. It has a general mood of reflecting on where we all are at this time of life."[41]

On November 10, 2009, Kristofferson was honored as a BMI Icon at the 57th annual BMI Country Awards. Throughout his career, Kristofferson's songwriting garnered 48 BMI Country and Pop Awards.[42] He later remarked, "The great thing about being a songwriter is you can hear your baby interpreted by so many people that have creative talents vocally that I don't have."[43] Kristofferson had always denied having a good voice, and had said that as he had aged, any quality it once had was beginning to decay.[44]

In December 2009, it was announced that Kristofferson would be portraying Joe on the upcoming album Ghost Brothers of Darkland County, a collaboration between rock singer John Mellencamp and novelist Stephen King.[45]

On May 11, 2010, Light in the Attic Records released demos that were recorded during Kristofferson's janitorial stint at Columbia. Please Don't Tell Me How the Story Ends: The Publishing Demos was the first time these recordings were released and included material that would later be featured on other Kristofferson recordings and on the recordings of other prominent artists, such as the original recording of "Me and Bobby McGee".[citation needed]

On June 4, 2011, Kristofferson performed a solo acoustic show at the Maui Arts and Cultural Center, showcasing both some of his original hits made famous by other artists, and newer songs.[citation needed]

In early 2013, Kristofferson released a new album of original songs called Feeling Mortal.[46] A live album titled An Evening With Kris Kristofferson was released in September 2014.[47]

Kristofferson voiced the character Chief Hanlon of the NCR Rangers in the hit 2010 video game Fallout: New Vegas.[48]

In an interview for Las Vegas magazine Q&A by Matt Kelemen on October 23, 2015, he revealed that a new album, The Cedar Creek Sessions, recorded in Austin, would include some old and some new songs.[49] In December 2016, the album was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Americana Album.[50]

Kristofferson covered Brandi Carlile's "Turpentine" on the 2017 album Cover Stories.[51]

Kristofferson performed, with assistance from Carlile, the Joni Mitchell composition "A Case of You", from the 1971 Mitchell album Blue, on November 7, 2018, at the Both Sides Now – Joni 75 A Birthday Celebration to celebrate the 75th birthday of Mitchell.[52]

In June 2019, Kristofferson was announced as being one of the supporting artists for a Barbra Streisand "exclusive European concert" on July 7 in London's Hyde Park as part of the Barclay's Summertime Concert series.[53]

In January 2021, Kristofferson announced his retirement.[54] His final concert was held in Fort Pierce, Florida, at the Sunrise Theatre on February 5, 2020, accompanied by the Strangers.[55]

Political views and advocacy

[edit]Kristofferson was a vocal opponent of the Gulf War and Iraq War and a critic of a number of United States military interventions and foreign policy positions, including the United States invasion of Panama and U.S. support of the Contras during the Nicaraguan Revolution and of the Apartheid government in South Africa.[56]

Kristofferson's debut LP included a pro-Vietnam war song, but he said that he later became an opponent of the war after speaking with returning soldiers who had seen combat. Speaking about a soldier who had told him that he had witnessed other soldiers throwing people out of helicopters during interrogation, Kristofferson said, "The notion that you could make a young person do something so inhumane to another soldier—or even worse, a civilian—convinced me that we were in the wrong." Kristofferson called himself a "dove with claws" and remained proud of his military service in spite of his anti-imperialist views.

In a 1991 interview on New Zealand TV, he condemned media support for the Gulf War, saying "The lapdog media cranks out propaganda that would make a Nazi blush."[57] Kristofferson was a supporter of the United Farm Workers and appeared at several rallies and benefits for them, campaigning with Cesar Chavez for the passage of Proposition 14. He continued to play at benefits for the UFW through the 2010s. In 1987, he played at a benefit concert for Leonard Peltier with Jackson Browne, Willie Nelson and Joni Mitchell. In 1995, he dedicated a song to Mumia Abu-Jamal at a concert in Philadelphia, and was booed by the crowd.[58]

He performed in benefit concerts for Palestinian children, and said that he "found a considerable lack of work as a result." At a Bob Dylan anniversary concert shortly after Sinead O'Connor's protest on Saturday Night Live, he showed solidarity with her when she was booed by the crowd.[59]

Personal life

[edit]In 1961, Kristofferson married his longtime girlfriend Frances "Fran" Mavia Beer, but they divorced in 1969.[11][60][61] Kristofferson briefly dated Janis Joplin before her death in October 1970.[60] His second marriage was to singer Rita Coolidge in 1973, ending in divorce in 1980.[4][60] Kristofferson married Lisa Meyers in 1983.[60]

Kristofferson and Meyers owned a home in Las Flores Canyon in Malibu, California,[38] and maintained a residence in Hana, Hawaii, on the island of Maui.[60] Kristofferson had eight children from his three marriages: two from his first marriage, one from his second marriage, and five from his marriage to his third wife.[62]

Kristofferson said that he would like the first three lines of Leonard Cohen's "Bird on the Wire" on his tombstone:[63][64]

Like a bird on the wire

Like a drunk in a midnight choir

I have tried in my way to be free

Death

[edit]Kristofferson died at his home on Maui on September 28, 2024, at the age of 88.[65][66]

Discography

[edit]- Studio albums

- Kristofferson (1970)

- The Silver Tongued Devil and I (1971)

- Border Lord (1972)

- Jesus Was a Capricorn (1972)

- Full Moon (with Rita Coolidge) (1973)

- Spooky Lady's Sideshow (1974)

- Breakaway (with Rita Coolidge) (1974)

- Who's to Bless and Who's to Blame (1975)

- Surreal Thing (1976)

- Easter Island (1978)

- Natural Act (with Rita Coolidge) (1978)

- Shake Hands with the Devil (1979)

- To the Bone (1981)

- Repossessed (1986)

- Third World Warrior (1990)

- A Moment of Forever (1995)

- The Austin Sessions (1999)

- This Old Road (2006)

- Closer to the Bone (2009)

- Feeling Mortal (2013)

- The Cedar Creek Sessions (2016)

Filmography

[edit]Awards and nominations

[edit]| Year | Association | Category | Nominated work | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Country Music Association Awards | Song of the Year | "Sunday Mornin' Comin' Down" | Won |

| 1973 | "Why Me" | Nominated | ||

| Single of the Year | Nominated | |||

| Academy of Country Music Awards | Song of the Year | Nominated | ||

| BAFTA Awards | Best Newcomer | Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid | Nominated | |

| 1974 | Academy of Country Music Awards | Song of the Year | "One Day at a Time" | Nominated |

| 1976 | Golden Globe Awards | Best Actor in a Musical | A Star Is Born | Won |

| 1984 | Academy Awards | Best Original Score | Songwriter | Nominated |

| 1985 | Country Music Association Awards | Single of the Year | "Highwayman" | Nominated |

| Video of the Year | Nominated | |||

| Academy of Country Music Awards | Single of the Year | Won | ||

| Video of the Year | Nominated | |||

| Album of the Year | Nominated | |||

| 2003 | Americana Music Honors & Awards | Free Speech Award | Himself | Won |

| 2005 | Academy of Country Music Awards | Cliffie Stone Pioneer Award | Won | |

| 2013 | Poets Award | Won | ||

| 2019 | Country Music Association Awards | Lifetime Achievement Award | Himself | Won |

Grammy Awards

[edit]Kristofferson has won three competitive Grammys from thirteen nominations. He received the Lifetime Achievement Award in 2014.[67]

| Year | Category | Nominated work | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | Song of the Year | "Me and Bobby McGee" | Nominated |

| "Help Me Make It Through the Night" | Nominated | ||

| Best Country Song | Won | ||

| "Me and Bobby McGee" | Nominated | ||

| "For the Good Times" | Nominated | ||

| 1973 | "Why Me" | Nominated | |

| Best Male Country Vocal Performance | Nominated | ||

| Best Country Performance by a Duo or Group | "From The Bottle To The Bottom" (with Rita Coolidge) | Won | |

| 1974 | "Loving Arms" (with Rita Coolidge) | Nominated | |

| 1975 | "Lover Please" (with Rita Coolidge) | Won | |

| 1985 | "Highwayman" (with the Highwaymen) | Nominated | |

| 1990 | Grammy Award for Best Country Collaboration with Vocals | Highwayman 2 | Nominated |

| 2014 | Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award | Himself | Won |

| 2016 | Best Americana Album | The Cedar Creek Sessions | Nominated |

References

[edit]- ^ "Kris Kristofferson | Artist | GRAMMY.com". grammy.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2024. Retrieved October 1, 2024.

- ^ "Death claims famed pilot". The Times. San Mateo, California. January 4, 1971. p. 3. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

Henry C. Kristofferson, 65, famed pilot and former division manager for Pan American World Airways when he was a resident of San Mateo, died... two sons, Kraig and Kris, who has recently won fame as a folk music and country-western singer.

- ^ O'Connor, Colleen. "Kris Kristofferson Following his passions – wherever they may lead". dallasnews.com – Archives. Archived from the original on June 22, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ^ a b Zompolis, Gregory N. (2004). Images of America, San Mateo. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. pp. 60–65. ISBN 0738529567.

- ^ "Kris Kristofferson Short Stories". Kris Kristofferson by Fans, for Fans. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ^ interview on Hawaii Public Radio, June 2, 2011

- ^ "Kristoffer Kristofferson". Sports Illustrated. (A Pat on the Back). March 31, 1958. p. 80. Archived from the original on October 1, 2019. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ "Acts of Will". Pomona College Magazine (Winter 2004). Archived from the original on September 7, 2013. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ^ "1973". Pomona College Timeline. November 7, 2014. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ "Kristofferson entry on Rhodes Trust database". Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Levens, R.G.C., ed. (1964). Merton College Register 1900–1964. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. p. 505.

- ^ Schneider, Jason "Kris Kristofferson: the Pilgrim's Progress" Exclaim! October 2009.

- ^ "Oh Boy Records | Kris Kristofferson Bio". Ohboy.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2009. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ^ [1] Archived September 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Kris Kristofferson Bio". CMT. Archived from the original on February 26, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ^ Vergun, David (March 23, 2021). "Sports Heroes Who Served: Singer, Songwriter, Actor Kris Kristofferson Is Also an Army Veteran". Defense.gov. Archived from the original on September 30, 2024. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- ^ Miller, Stephen (December 17, 2009). Kristofferson: The Wild American. Omnibus Press. ISBN 9780857121097. Archived from the original on September 30, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Kris Kristofferson's Rock And Rules | Clash Music Exclusive Interview". Clashmusic.com. July 27, 2010. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ Cheryl McCall. "Can't Keep Kris Down". People. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ "Kris Kristofferson". Biography.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ Schrodt, Paul (January 29, 2007). "Kris Kristofferson Interview – Quotes about his Kids, Sex, and Rock and Roll". Esquire. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ^ "WIllie and Kris at the AVA's!". YouTube. June 23, 2011. Archived from the original on December 17, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ "8th Annual Veterans Awards". V-r-a.org. November 26, 2002. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ^ Ethan Hawke (April 16, 2009), "Kris Kristofferson: The Last Outlaw Poet", Rolling Stone, archived from the original on February 28, 2022, retrieved June 29, 2021

- ^ Ron Thibodeaux, "He Made It through the Night", Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine New Orleans Times-Picayune, November 29, 2006.

- ^ Hawke, Ethan (April 16, 2009). "The Last Outlaw Poet". Rolling Stone. No. 1076. p. 57. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

- ^ "Never a great singer, Kris Kristofferson has had an amazing career nonetheless" Archived February 28, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ Betts, Stephen L. (July 16, 2014). "Kris Kristofferson's Awkward CMA Win". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ Himes, Geoffrey (August 31, 2016). "Kris Kristofferson at Newport Folk Festival". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on October 1, 2024. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ Murrells, Joseph (1978). The Book of Golden Discs (2nd ed.). London: Barrie and Jenkins Ltd. p. 330. ISBN 0-214-20512-6.

- ^ "Al Green – For The Good Times". discogs.com. Retrieved November 9, 2024.

- ^ "Fire Down Below (1997)". tcm.com. Turner Classic Movies, Inc. Retrieved November 14, 2024.

- ^ Holden, Stephen. "Realism, Both Magic and Downright Mean". The New York Times. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ York, M. (2024). The Highwaymen – Songs & Stories: The Mount Rushmore of Country Music. BookPatch LLC. p. 67. ISBN 979-8-88567-194-1. Archived from the original on October 1, 2024. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "Kris Kristofferson Biography" "CMT" 2004.

- ^ Kristofferson, Kris. "They Killed Him". bobdylan.com. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- '^ John Corry, TV VIEW; LESSONS TO BE LEARNED FROM 'AMERKIA NYTime Feb. 22, 1987.

- ^ a b Strauss, Neil (June 6, 2016). "Kris Kristofferson: An Outlaw at 80". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 22, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- ^ "Americana Awards Honor Kristofferson, Douglas, Prine and Phillips". BMI. October 8, 2003. Archived from the original on October 1, 2024. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ Gerome, John (March 12, 2007). "Kris Kristofferson to Receive CMT Award". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 28, 2019. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ "Kris Kristofferson". newwestrecords.com. Archived from the original on February 15, 2009. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ "Kris Kristofferson to be Honored as Icon at 57th Annual BMI Country Awards". bmi.com. June 30, 2009. Archived from the original on October 1, 2024. Retrieved September 15, 2010.

- ^ 'I never doubted once', country icon says. CNN. November 11, 2009. Archived from the original on November 13, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ "Kris Kristofferson on being an aging heartthrob, singer and actor". The Washington Post.

- ^ "John Mellencamp Official Site | A Year-End Conversation with John". Mellencamp.com. December 15, 2009. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ^ Conway, Tom. "Kristofferson 'Feeling Mortal' but good". Southbendtribune.com. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "An Evening with Kris Kristofferson: The Pilgri..." AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ Staff, G. R. (August 10, 2010). "Fallout: New Vegas Has Some Big Name Voice Talent". Game Rant. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "Q&A: Kris Kristofferson". Las Vegas Magazine. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ "2017 Grammy Awards: Complete list of nominees". Los Angeles Times. December 6, 2016. Archived from the original on January 14, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ "Cover Stories: Brandi Carlile Celebrates 10 Years of the Story (An Album to Benefit War Child) by Various Artists". iTunes. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- ^ "Column: Jeff Simon: An all-star birthday party for Joni Mitchell and others". Buffalo News. April 4, 2019. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- ^ "British Summertime Festival: Only Barbara Streisand could sing Silent Night in mid-Summer". kcwlondon.co.uk. KCW Today. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ "Kris Kristofferson Camp Confirms He Has Retired: 'It Just Felt Very Organic'". Variety. January 28, 2021. Archived from the original on October 1, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ "Sunrise Theatre". Sunrisetheatre.com. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- ^ Benitez-Eves, Tina (March 18, 2024). "The Not-So-Subtle Political Commentary Behind Kris Kristofferson's 1990 Single 'Don't Let the Bastards (Get You Down)'". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on October 1, 2024. Retrieved October 1, 2024.

- ^ Lehmann, Chris (October 1, 2024). "How Kris Kristofferson Beat the Devil". ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved October 2, 2024.

- ^ Browne, David (October 2, 2024). "Kris Kristofferson Paid a Price for His Social Activism. He Didn't Care". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 2, 2024. Retrieved October 2, 2024.

- ^ Barton, Laura (September 30, 2024). "Kris Kristofferson: the soldier turned star made a tough life into tender poetry". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on October 2, 2024. Retrieved October 2, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Campbell, Courtney (August 30, 2020). "Kris Kristofferson + Lisa Meyers: Inside Their 37-Year Love Story". Wideopencountry.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2024. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ Cashmere, Paul (September 29, 2024). "Kris Kristofferson Dies at Age 88". Noise11. Archived from the original on September 30, 2024. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "Family for Kris Kristofferson". Tcm.com. June 22, 1936. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- ^ Schneider, Jason. "Kris Kristofferson The Pilgrim's Progress". Exclaim.ca. Archived from the original on October 1, 2024. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- ^ Cohen, Leonard, Greatest hits, Sony Music Entertainment Inc, CD booklet, p. 4, OCLC 863239766, archived from the original on October 1, 2024, retrieved February 12, 2023

- ^ Morris, Chris (September 29, 2024). "Kris Kristofferson, Country Music Legend and 'A Star Is Born' Leading Man, Dies at 88". Variety. Archived from the original on October 1, 2024. Retrieved September 29, 2024.

- ^ "US country music star Kris Kristofferson dies, aged 88". BBC. Archived from the original on September 30, 2024. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "Kris Kristofferson". GRAMMY.com. November 19, 2019. Archived from the original on September 30, 2024. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Bernhardt, Jack. (1998). "Kris Kristofferson". In The Encyclopedia of Country Music. Paul Kingsbury, Editor. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 286–287.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Kristofferson fan website

- The Old Oxonion Blues 1959 profile in Time

- Kristofferson at the Country Music Hall of Fame

- Kris Kristofferson at New West Records

- Kris Kristofferson at AllMovie

- Kris Kristofferson at AllMusic

- Kris Kristofferson discography at Discogs

- Kris Kristofferson at IMDb

- Kris Kristofferson at the TCM Movie Database

- Kris Kristofferson at Broadcast Music, Inc.

- 1936 births

- 2024 deaths

- 20th-century American guitarists

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 21st-century American male actors

- Alumni of Merton College, Oxford

- American acoustic guitarists

- American aviators

- American country guitarists

- American country singer-songwriters

- American folk guitarists

- American male film actors

- American male guitarists

- American male singer-songwriters

- American people of Swedish descent

- American Rhodes Scholars

- American rock guitarists

- Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Columbia Records artists

- Country Music Hall of Fame inductees

- Country musicians from Texas

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Guitarists from Texas

- Light in the Attic Records artists

- Male actors from Texas

- Members of the Country Music Association

- Mercury Records artists

- Military personnel from Texas

- Monument Records artists

- New West Records artists

- Outlaw country singers

- People from Brownsville, Texas

- Players of American football from Cameron County, Texas

- Pomona College alumni

- Pomona-Pitzer Sagehens football players

- Progressive country musicians

- San Mateo High School alumni

- Singer-songwriters from Texas

- Texas Democrats

- The Highwaymen (country supergroup) members

- United States Army aviators

- United States Army officers

- Warner Records artists